Richard Avedon isn’t a street photographer— nor did he consider himself one. However, he did shoot street photography in his life, in Italy, New York, Santa Monica, and more.

I was particularly drawn to Richard Avedon because I have a fascination with portraiture and the human face. Even for my personal street photography, I might consider it “street portraiture.”

I have recently binged on everything I could about Avedon— and have gained a ton of inspiration from his photography, his love of life, and his personal philosophies. I hope you enjoy these lessons as much as I did.

1. Your photos are more about yourself (than your subject)

One of the touchy subjects when photographing a subject is to capture their “authentic” self— and not impose so much of yourself onto them.

However Avedon took the opposite approach. He openly acknowledged that as a photographer— it was he who was in control. His vision of an artist was more important than how his subjects saw themselves.

In a sense— I think Avedon was striving to capture what he thought was the “true” authenticity of his subjects.

Avedon starts off by sharing that most people have things about themselves that they don’t want to show:

“I am not necessarily interested in the secret of a person. The fact that there are qualities a subject doesn’t want me to observe is an interesting fact (interesting enough for a portrait). It then becomes a portrait of someone who doesn’t want something to show. That is interesting.”

Avedon elaborates on capturing the “truth” behind a person:

“There is no truth in photography. There is no truth about anyone’s person. My portraits are much more about me than they are about the people I photograph. I used to think that it was a collaboration, that it was something that happened as a result of what the subject wanted to project and what the photographer wanted to photograph. I no longer think it is that at all.”

“It is complicated and unresolved in my mind because I believe in moral responsibility of all kinds. I feel I have no right to say, “This is the way it is” and in another way, I can’t help myself. It is for me the only way to breathe and to live. I could say it is the nature of art to make such assumptions but there has never been an art like photography before. You cannot make a photograph of a person without that person’s presence, and that very presence implies truth. A portrait is not a likeness. The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is truth.”

He continues by sharing the control he has over the subject (and scene):

“The photographer has complete control, the issue is a moral one and it is complicated. Everyone comes to the camera with a certain expectation and the deception on my part is that I might appear to be indeed part of their expectation. If you are painted or written about, you can say: but that’s not me, that’s Bacon, that’s Soutine; that’s not me, that’s Celine.”

In another interview, Avedon continues sharing his thoughts on the conundrum of showing “truth” in a portrait:

“It is complicated and unresolved in my mind because I believe in moral responsibility of all kinds. I feel I have no right to say, “This is the way it is” and in another way, I can’t help myself. It is for me the only way to breathe and to live. I could say it is the nature of art to make such assumptions but there has never been an art like photography before. You cannot make a photograph of a person without that person’s presence, and that very presence implies truth.”

The part below is pure gold:

“A portrait is not a likeness. The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is truth.”

In another interview, Avedon elaborates on the distinction between “accuracy” and “truth”— and how subjective it is:

“[Photographs are] representations of what’s there. “This jacket is cut this way”; that’s very accurate. This really did happen in front of this camera at this… at a given moment. But it’s no more truth… the given moment is part of what I’m feeling that day, what they’re feeling that day, and what I want to accomplish as an artist.”

Avedon also shares his thoughts on how cameras can lie, and how photographers say what they want to say (depending on when they hit the shutter):

“Camera lies all the time. It’s all it does is lie, because when you choose this moment instead of this moment, when you… the moment you’ve made a choice, you’re lying about something larger. Lying is an ugly word. I don’t mean lying. But any artist picks and chooses what they want to paint or write about or say. Photographers are the same.”

Takeaway point

I think when we’re shooting on the streets— we are painting our subjective views of the world with our camera (rather than an ‘objective’ view of the world). I think in street photography— we have less of an ethical duty (than documentary or photojournalists) to show the “truth.”

I think ultimately the photos we take (as Avedon said) — are more of a reflection who we are (than the subjects).

For example, I am personally drawn to people who look depressed, lost, and stuck in solitude. Even though I am a generally optimistic person— my studies in sociology have trained me to be a social critic. I tend to see a lot of negativity in everyday life.

However on the flip side, I know a lot of photographers whose photos are very happy. For example, Kurt Kamka has photos of people all (or mostly) smiling. He is one of the happy guys I have met, and his positivity and love shows through his photos.

So know that although photography is a form of communication and a two-way street between you and your subject, you still have the ultimate control as a photographer.

Make your photos personal, and realize that the photos you take are more of a self-portrait of yourself (than anything else).

2. On controversy

Richard Avedon’s photos have always been controversial. Many of his critics called him cold, calculating, and very unjust towards his subjects. Many of his subjects also don’t like the way they end up being portrayed.

a) Photographing people looking their best (or not)

In the below excerpt, Avedon shares his thoughts that everyone is always trying to look their best (which isn’t always accurate). Furthermore, he doesn’t take these complaints too seriously:

JEFFREY BROWN: Not everyone is always happy with the results. Avedon took this portrait of the renowned literary critic Harold Bloom.

RICHARD AVEDON: And he said, “I hate that picture. It doesn’t look like me.” Well, for a very smart man to think that a picture is supposed to look like him… would you go to Modigliani and say, “I want it to look like me?”

JEFFREY BROWN: But, see, we think of photography differently, don’t we? We take pictures of each other all the time, and we want it… we expect it to look like us.

RICHARD AVEDON: How many pictures have you torn up because you hate them? What ends up in your scrapbook? The pictures where you look like a good guy and a good family man, and the children look adorable– and they’re screaming the next minute. I’ve never seen a family album of screaming people.

JEFFREY BROWN: You do have, though, people say, “I don’t like this; this isn’t me.”

RICHARD AVEDON: Pretty general response.

JEFFREY BROWN: It doesn’t worry you?

RICHARD AVEDON: No. Worry? I mean, it’s a picture, for God’s sake.

b) On manipulating his subjects

Furthermore, there have been times when Avedon would purposefully manipulate his subjects to get a photo he wanted— which he felt was more “authentic”:

“There are times when it is necessary to trick the sitter into what you want. but never for the sake of the trick.”

For example when he took this famous photo of the Windsors:

“I would go every night to the casino in Nice— and I watched them. I watched the way she was with him, the way they were with people. I wanted to bring out the loss of humanity in them. Not the meanness and there was a lot of meanness and narcissism. So I knew exactly what I had to try to accomplish during the sitting. I photographed them in their hotel suite in New York. And they had their pug dogs, and they had their ‘ladies home journal’ faces on— they were posing, royally. And nothing (if not for a second)— anything I had observed when they were gambling, presented to me. And I did a kind of ‘living by your wits’. I knew they loved their dogs. and I told them, ‘If i seem a bit hesitant or disturbed— its because my taxi ran over a dog.’ and both of their faces dropped, because they loved dogs, a lot more than they loved Jews. The expression on their faces is true— because you can’t evoke an expression that doesn’t come out of the life of a person.”

c) On capturing people when they feel vulnerable

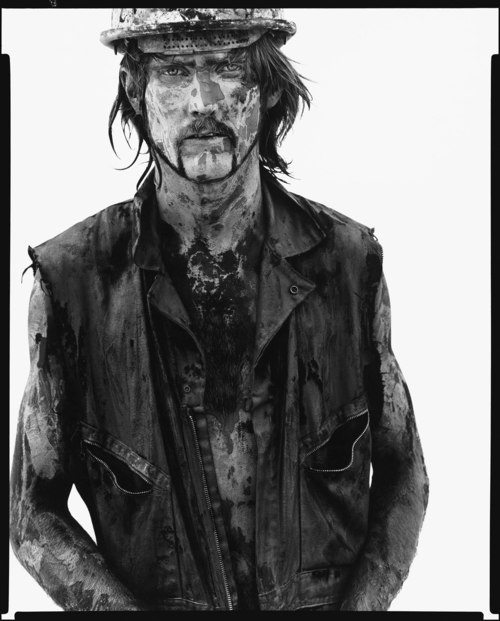

In his greatest project (in my opinion) “In the American West” — he photographed a girl named Sandra Bennett (who ended up being on the front cover of the book). She is beautiful with freckles, but pensive— and looks a bit disconcerted.

Years after he took the photo, Avedon and some reporters tracked down his past subjects. Sandra (now an adult) told the reporter:

“The picture was awful— it was your worst hair day, clothes day, the worst photo of your life you want to bury. I was mortified. I was a senior in high school, I was homecoming queen, and I had this photo coming to haunt me.”

Sandra then confronts Avedon face-to-face and says the following:

“What was very difficult for me— was that you caught me vulnerable here. But also bare-bottom, very exposed – where I tried to cover everything.”

Avedon then says in response to Sandra how (ultimately) he is the one who had control over the situation:

“You can’t say you weren’t there in the picture you have to accept— you are there, and the control is with the photographer. I have the control in the end, and I can’t do it alone. You have a lot to say— which by that I mean the way you look, confront the camera, all the experience whether you are trusting or not. In the end, I can tear the pictures up— choose the smiling or serious one. Or exaggerate something through the printing. It is lending yourself to artists.”

d) Photography vs reportage/journalism

Avedon also had some interesting views when it comes to photography — being more like fiction (than anything else):

“I think the larger issue is that photography is not reportage, it is not journalism— it is fiction. When I go to the west and do the working class (it is more about the working class than the west)—it is my view. Like John Wayne is Hollywood’s view. So it means my idea of the working class is a fiction.”

e) On photography being invasive

Avedon shares some thoughts on his work being invasive— and how important it is to make “disturbing” photos that emotionally effect the viewer:

“It’s so strange to me that anyone would ever think that a work of art shouldn’t be disturbing or shouldn’t be invasive. That’s the property of work— that’s the arena of a work of art. It is to disturb, it to make you think, to make you feel. If my work didn’t disturb from time to time, it would be a failure in my own eyes. It’s meant to disturb— in a positive way.”

Takeaway point:

I don’t think any artist who wants to achieve greatness can do so without pissing some people off.

But as a photographer— who are you ultimately trying to please? Yourself, or your critics?

Who cares about these critics who may hate on your work. They are too busy sitting on their laptops, and criticizing the work of others (because they are jealous, or just dissatisfied with their own work).

Avedon had tons of criticism in his work in his lifetime. But he ignored it. He was constantly furious with doing his work— creating new work, breaking out of the little boxes that critics were trying to put him in— combining portraiture, commercial photography, documentary, and fine art.

I think if Avedon listened to all the criticisms he received during his life (and just stopped photographing)— we wouldn’t have this incredible body of work that he left behind.

So as a takeaway point for you— follow your own heart. Follow your gut. Follow your own instincts. Don’t give a flying fuck what others think about your work— or how they will criticize your work.

As Andy Warhol once said— while they are busy judging your work (whether it is good or not) — just keep creating more work and creatively flourish.

Your photos will never be subjective, and appreciated 100% by your audience.

There is a lovely quote on criticism that my good friend Greg Marsden shared with me:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.” – Theodore Roosevelt

3. On his work ethic

There are few photographers who were as obsessive, hard-working, and perfectionist as Avedon was.

a) Importance of working hard (everyday)

Avedon shares a bit of his personal background, and his creative routine:

“There’s a biological factor if you can do it, or who has the ability to do it. A lot of people want to be photographers, and it wasn’t a master plan [for me]. I just loved to get up every morning [I still do]. In the morning, I’m ready to work at 9am. It’s a gift that was given to me. Maybe I was a shrimp, maybe in the locker room I was a failure, maybe I don’t know what it was. But I had a bedroom, and the kids were playing on the streets, and i would draw the shade– and it was a little split, and i could see out of them. I don’t know where it comes from, I don’t think anybody does. But at some moment, it comes together if you’re lucky.”

Avedon also shares the importance of working hard everyday at your creative work:

“If you do work everyday at your life, you get better at it. The trick is: to keep it alive. To keep it crucial.”

b) On putting pressure on yourself

Avedon also harnesses some of the fear he has — to keep his wits sharp and to make great photos:

“There’s nothing hard about photography. I get scared, and I’m longing for the fear to come back. I feel the fear when i have the camera in hand. I’m scared like when an athlete is scared, you’re going for the high jump. You can blow it. That’s what taking a photo is.”

c) The sacrifice he paid with his family

Unfortunately, Avedon’s workaholism did pay a price with his family:

“I think when you work as I’ve worked– theres something I didn’t do something successfully, which is my family life. Marriage. I don’t think you can do it all.”

However Avedon says on the other hand— he has no regrets:

“I think if you pay that price, that’s not a terrible price. There is no guarantee any family life is going to work out.”

d) Disregarding compliments

One of the greatest strengths of Avedon was that he didn’t care much for compliments. I think his comes from his tough training, when he worked at Harper’s Bazaar with Brodovich (a man with very high standards):

“Brodovich was the father. He was very much like my father. Very withdrawn and disciplined and very strong values. He gave no compliments, Which killed a lot of young photographers— they couldn’t take it. I didn’t believe compliments. I never believed compliments even until this day. So I responded to the kind of toughness plus the aristocracy and standards.”

While working at Harper’s Bazaar, the 3 closest people he worked with were all perfectionists. He said the following:

“The addiction of perfection of those three people — and that’s why those pictures hold.”

e) On never being satisfied

Even with one of Avedon’s most famous elephant photo— he considers the photo a failure (for a small detail):

“I don’t know why I didn’t have the sash blowing out to the left to complete the line of the picture. The picture will always be a failure to me, because the sash isn’t out there.”

f) On shooting until the end

It is incredible— Avedon shot and worked everyday until he died at 81 (while on assignment).

Avedon reflects on the work he creates:

“The thing that has happened to me lately is the sense I didn’t take the photos. That they have a life of their own. It’s endlessly mysterious to me.”

When Avedon was still alive— he also shared how he wanted to keep working, and producing new work (even as an older man):

“I’ve become my own widow. I’m in charge of my archives, I create books— I create exhibitions. but it will be over. And when i’s over then I’ll read and rest, and begin to become a photographer again— I hope. My god in the question of being an older man with passion is Matisse, because when one would have thought he had done everything— he got into bed and re-created color and did the most beautiful work of his life, and most modern work of his life. If i can be reborn for the few years that are left to me— it would make me very happy. And if not, I’ll either really go with full force or ill stop.”

g) Don’t feel you need to prove yourself to others

Another golden nugget of wisdom (applies not just to photography, but life): don’t feel like you need to prove yourself to others. Avedon shares below:

“What I like about being older is that I don’t feel I need to prove myself anymore. Like an onion peeling, I don’t go to dinner parties [been there], I don’t work for magazines anymore. What’s the unnecessary? What’s important? Doing the work

making the work better. Doing the job better than I did before, and the few close friends in the kitchen you get together with. We sit down and talk, really. There is no turning to the left and right– and asking people about random talk.”

h) On thinking of your own mortality

I think there is nothing better to keep you motivated (than the thought of death).

For example, in 1974, he fell dangerously ill to inflammation of heart, and kept working. The second attack was life threatening. At around the time (when he was 60) — he started his “In the American” west series (which lasted 5 years). He was motivated much by his older age, and I think it is that thought of death which really propelled him to create this incredible body of work.

Avedon shares:

“I think my best work as a body of work is ‘In the American West’. I did the western photos when I was around 60, and I think that — being 60 is different from 30,40,50— you begin to get a sense of your own mortality. I think my aging, the sort of stepping into the last big chapters— was embedded in this body of work. As deeper connection to those people who were strangers. Because of my condition of that time.”

Of course, the work wasn’t without controversy. Critics loved it or hated it. Avedon was charged for exploiting his subjects, and falsifying the west. Avedon shares:

“The book was called ‘In the American West’ — which really set off an enormous, hostile response to the book. What was an east coast successful photographer doing photographing working class people in the west? Was this really the west, and what was he doing?”

Takeaway point:

I think “talent” is overrated in photography and the arts. Based on all the great creatives I have studied— it is their hard work ethic which ties them all together.

Avedon was never satisfied with his work. He wanted to always push it to the next level. He was incredibly self-centered in his work, because he believed in it. He disregarded what others thought of him and his photos— he had this fire in his heart that kept him alive.

He photographed until he died at 81. Now that is a life of photography I would love to emulate.

Also as a big takeaway point: realize that you have nothing to prove with your photography. You don’t need to impress anybody — but yourself.

Focus on constantly improving your work, and put in the hours. Disregard everything else.

4. On how he photographed

To hear about Richard Avedon’s approach and signature style is fascinating.

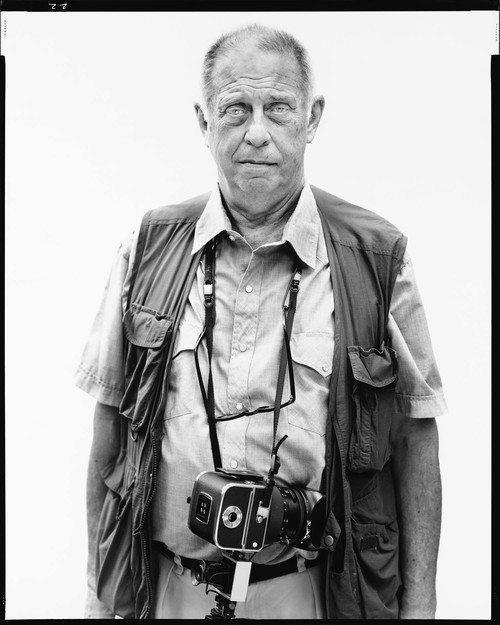

One of the things Avedon is most famous for is taking portraits on an 8×10 camera, with a totally white background, and black borders— with the human face as his main subject.

Paul Roth, who is the senior curator and director of photography and media arts, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C said the following about Avedon:

“In 1969, the tools Avedon used were the same tools he had used before. He photographed with a big 8×10 view camera, which was already kind of anachronistic at that time. It’s the kind of camera we associated more with Nadar in the 19th century. He photographed people against a white backdrop so that there was no contextualizing, no environment for us to locate or place them. He had done that before, but in 1969, he made it into a fetish. He would show the black border, the edges of his negative. He contrasted the white background against the black edge of the film in a way that was very radical. It made the pictures very tough and aggressive. Furthermore, bodies would be sliced, feet cut off at the ankles, heads cut off at the crown. He didn’t use flattering, chiaroscuro lighting. And he was fascinated by age. He had this wonderful expression called avalanche. He would describe seeing age descending on a person like an avalanche, covering them over. So Avedon took great care to photograph the folds of skin, wrinkles, and moles, all with a very sharp lens. And that was also very radical. Traditionally portraiture idealizes its subject—and gives some sense of their clothes and surroundings. Avedon dispensed with all of that. It’s hard to overemphasize how radical that kind of portraiture was at the time.”

a) Focus on subtraction (saying no)

I find it fascinating that Avedon used negation as a big part of his photography. Addition via subtraction. Avedon shares:

“I work out of a series of “no’s”. No to distracting elements in a photograph. No to exquisite light. No to certain subject matter, no to certain people (I can’t express myself through). No to props. All these no’s force me into the yes. And I have no help. I have a white background, the person I’m interested in, and the thing that happens between us.”

b) On choosing faces

Nobody has photographed the human face more (or as well) as Richard Avedon. How does Avedon find an interesting face to photograph? A past assistant shares a story when working with Avedon:

“The very first weekend we worked together, we were walking through a stadium for the Rattlesnake Roundup in Sweetwater, Texas, and Dick said to me, “Which face would you choose?” I thought to myself, “You’re the famous photographer. You tell me,” but what he was doing was putting me on the spot right from the beginning to force me to look and to learn.”

The key: making a photograph that will last for many years:

“Whether he was considering a cowboy or a coal miner, Avedon would always ask, “Is that face going to hold the wall and be as riveting six years from now?” When you take a person out of context — out of the mine, out from beside the road with a vast expanse of Oklahoma prairie behind him — then you really have to have a face that’s going to say something.”

c) Harnessing your own emotions

Avedon was also quite in-touch with his emotional side in his photography:

“To be an artist— to be a photographer, you need to nurture the thing that most people discard. You have to keep them alive in order to tap them. It’s been important my entire life not to let go of anything which most people would throw in the ashcan. I need to be in touch with my fragility, the man in me, the woman in me. The child in me. The grandfather in me. all these things, they need to be kept alive.”

Avedon also harnesses much fear into his work:

“I think I do photograph what I’m afraid of. Things I couldn’t deal with the camera. My father’s death, madness, when I was young—women. I didn’t understand. It gave me a sort of control over the situation which was legitimate, because good work was being done. And by photographing what I was afraid of, or what I was interested in— I laid the ghost. It got out of my system and onto the page.”

He also shares his thoughts on death:

JEFFREY BROWN: You wrote in the catalog essay that “Photography is a sad art.” Why?

RICHARD AVEDON: It’s something about a minute later, it’s gone, it’s dead, and the only thing that lives on the wall is the photograph. And do you realize that in this exhibition, almost everyone is dead? They’re all gone, and their work lives, and the photograph lives. They never get old in a photograph. So it’s sad in that way.

Avedon even photographed his father, who was losing his battle with cancer (on the brink of death). When asked why he made the series, Avedon said:

”It gave me a sort of control over the situation. I got it out of my system and onto the page.”

Avedon was also able to touch into the darker emotions behind many of the famous faces he photographed:

“People — running from unhappiness, hiding in power — are locked within their reputations, ambitions, beliefs.”

d) On dancing with your subjects

Much of Avedon’s work has great energy and vitality to it. For his early fashion work, he would often dance with his models with his Rolleiflex— and his subjects would respond by dancing as well. This lead to a body of work which had energy, vibrance, and edginess.

Avedon shares his thoughts on capturing movement:

“One of the most powerful parts of movement is that it is a constant surprise. You don’t know what the fabric is going to do, what the hair is going to do, you can control it to a certain degree— and there is a surprise. And you realize when I photograph movement, I have to anticipate that by the time it has happened— otherwise it’s too late to photograph it. So there’s this terrific interchange between the moving figure and myself that is like dancing.”

Even when photographing his subjects, he would tell them to jump, and to “jump higher!”

e) On photographing the face

Avedon is most famous for photographing fascinating faces. This is what he describes his approach in photographing faces:

“Different animals have different kinds of eyes for accomplishing what their goals are. An eagle has a literal zoom lens in the eye so that from way above he can zoom down into the rodent he is going to attack. And in the way I think my eyes always went to what i was interested in— the face.”

He elaborates on how he analyzes faces:

“I think I’m sort of a reader— I used to love handwriting analysis. But that’s nothing compared to reading a face. I think if I had decided to go into the fortune telling business, I would have probably been very good. What happens to me in work— I look for something in a face, and I look for contradiction, complexity. Something that are contradictory and yet connected.”

Takeaway point:

What I learned from Avedon is the importance of capturing soul, energy, and emotions from your subjects.

Being interested in shooting portraits of strangers in the streets, I always try to channel my “inner-Avedon” — to try to quickly analyze a person, and try to create an image I have of them in my mind— which I think shows a part of them which is vulnerable or emotional.

I think there is nothing more difficult than photographing the human face. There is so much expression, intricacies, and subtleties in the human face.

Ultimately— I think Avedon’s most memorable images are the ones that are a bit unsettling, emotional, and controversial. Don’t shy away from controversy— just follow your own heart when photographing your subjects.

5. A message for photographers

In this excellent documentary on Richard Avedon (Darkness and Light) — he concludes with these words of wisdom to photographers:

“We live in a world of images. Images have replaced language — and reading. The responsibility to your role in history in whatever is going to happen to human beings— you are the new writers. And we can no longer be sloppy about what we do with a camera. You have this weapon in your hands which is a camera, and it is going to teach the world, it’s going to record the world, it is going to explain to the world and to the children that are coming — what this world was like. It is an incredible responsibility.”

Conclusion

Avedon is a man who lived with conviction and dedicated his entire, soul, and being into his photography and his work. There are few photographers who have had the work ethic of Avedon— and created such a diverse body of work.

Although Avedon is mostly known as an editorial, advertising, and portrait photographer— I still think his “In the American West” is one of the most personal and insightful portrait series done in America. And they were done mostly of strangers in the streets he met (very similar to shooting ‘street portraits’).

If you are interested in street portraits— devour the work of Avedon. Look at the way he captures the emotion and soul of his subjects. How he embraces ambiguity and complexity in the faces he captures. How he interacts with his subjects, and projects his own feelings onto his subjects.

And lastly, don’t be afraid of controversy. Follow your own heart, and photograph by channeling your own emotions. Make your photos personal— and never stop working.

Videos

Richard Avedon: Darkness and Light (one of my favorite documentaries)

Charlie Rose: Avedon Interview

Links

Books by Avedon

To see more work by Avedon, check out the Avedon Foundation.

Also check out the Richard Avedon iPad application — which is phenomenal and free.

1. Avedon at Work: In the American West

A fascinating look into how he photographed “In the American West.”

2. In the American West: Avedon

The photography book (if you are into street photography) that you definitely have to get.

3. Richard Avedon: Photographs 1946-2004

Over 200 photos of his best images. A solid volume to invest in.

4. Richard Avedon: Woman in the Mirror

An absolutely gorgeous volume of his iconic photos of women.

5. Avedon Fashion (1944-2000)

If you love fashion photography, the entire body of work from Avedon.

If you want more book recommendations (from other photographers), check out my list: 75+ Inspirational Street Photography Books You Gotta Own

Continue learning from the masters

- Alec Soth

- Alex Webb

- Anders Petersen

- Andre Kertesz

- Bruce Davidson

- Bruce Gilden

- Constantine Manos

- Daido Moriyama

- David Alan Harvey (Part 1) / David Alan Harvey (Part 2)

- David Hurn

- Diane Arbus

- Elliott Erwitt

- Eugene Atget

- Eugene Smith

- Garry Winogrand

- Helen Levitt

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Jacob Aue Sobol

- Jeff Mermelstein

- Joel Meyerowitz

- Joel Sternfeld

- Josef Koudelka

- Lee Friedlander

- Magnum Contact Sheets

- Magnum Photographers

- Mark Cohen

- Martin Parr

- Richard Kalvar

- Robert Capa

- Robert Frank

- Saul Leiter

- Stephen Shore

- The History of Street Photography

- Tony Ray-Jones

- Trent Parke

- Vivian Maier

- Walker Evans

- Weegee

- William Eggleston

- William Klein

- Zoe Strauss