All photographs in this article are copyrighted by Mark Cohen.

I think Mark Cohen is one of the greatest street photographers out there who isn’t as well known as his contemporaries. I’m sure you might have seen some videos of him on YouTube shooting with a flash without using the viewfinder. I have to admit, even to me– he seems a bit “creepy” when you see him working. However the reason he works the way he does is to create art– he feels that the end justifies the means.

I have been deeply inspired by his book: “Grim Street“– and I just pre-ordered a new book he has in the pipeline called “Dark Knees.” His imagery has inspired the way I shoot quite a bit (especially when it comes to photographing details and decapitating heads). Not only that, but it is quite inspirational to see him shoot in his small town for over 30 years.

Below are some lessons I have personally learned from Mark Cohen:

1. Shoot in your own backyard

We tend to romanticize photographing foreign and exotic places. But Mark Cohen has spent the majority of his time shooting street photography in Wilkes-Barre (a small Pennsylvania mine-town) and another area called Scranton for over 30 years.

Mark Cohen shares how all of the photos in his book “Grim Street” are all from his backyard, and the advantage of knowing your own neighborhood very well:

“I’m in my backyard making these. The whole country is my studio. I used to go work under a certain bridge if it was pouring, because people used to hide there from the rain. If it was a cloudy day, I would go to a different place. So I used these neighborhoods like a set. And I still use them like that. There are certain places I know that, if I go there in the evening– I like to take pictures at dusk– they will have a certain flavor even today.”

Furthermore, Cohen explains how he didn’t need to travel the world to take interesting photographs:

“I just made my photos in Wilkes-Barre and a few other places because I wasn’t the kind of photographer who liked to, or needed to, travel around the world. That reminds me, I saw something you had said about how artistic range effects an artist’s development over time. And I work on an extremely narrow range, in terms of my method and technical issues, too. It’s what is in my head that has developed over time. So I’ve just kept taking pictures in the same two counties [Wilkes-Barre and Scranton].”

Takeaway point:

There are many advantages to shoot in your own backyard and neighborhood. First of all, it is easily accessible– which means you can go shoot more often. Secondly, you will probably know the area better– and know which areas are more interesting to photograph, and when the light is good. Thirdly, you will probably create a more unique body of work that is different from photos you might see in New York City, Tokyo, or Paris.

So embrace your own backyard– and go out and shoot. If Cohen was able to shoot his own neighborhood for over 30 years and make an incredible body of work (Grim Street) so can you.

2. Focus on details

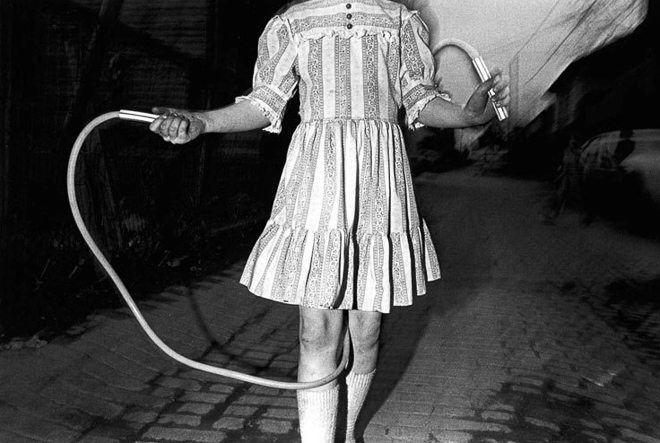

Another unique aspect of Cohen’s work is how he focuses on details in his images. His photos include close-ups of ankles, socks, teeth, zippers, elbows, and other small details we tend to overlook.

The great thing about him focusing on details is that formally it becomes more interesting. The images become more abstract. You focus on the geometry, angles, and lines of parts of the human body. It becomes more surreal.

Not only that, but another technique Mark Cohen often used in his work is cutting off heads. Some of his most interesting photos don’t include faces.

I feel this works for several ways: First of all, there is more of a sense of anonymity of the subjects. Secondly, this creates more surrealism in the shots. Thirdly, it makes the viewer more curious about the image, and makes it more open-ended.

Takeaway point:

A common mistake I see a lot of street photographers who are starting off make is trying to get too much in the frame. Trying to tell the whole story. Trying to get the full body in the shot.

I would rather recommend, try to focus on the details. Just focus on a subject’s face. Or his/her hands. Or feet. Or on interesting gestures. By showing less, you often show more.

Keep the images open-ended. And like a good movie, don’t spoil the ending by trying to tell the full story.

3. On using a flash

One of the most important tools in Mark Cohen’s arsenal is his small flash. He isn’t using a flash to piss off people. Rather, he is using it to illuminate his subjects, and create a surrealist type of image. He is trying to create a certain “look” in his photography and art.

Cohen explains in-detail why he likes to use a flash, and how he got inspired to start using it:

“I got a small flash-unit because I really liked the phenomenological effect I would get shooting at twilight. Also, I had seen some of Arbus’ flash-pictures at the MoMA show in ’72. I like Friedlander’s flash-pictures as well. So I started to just go and hook this little flash on my camera when I was walking around town. And then I became incredibly intrusive with it. When you take a flash-picture of somebody at night, you get a much more distinct and compact event.”

However Cohen does explain how intrusive shooting with a flash can be, and how much attention it can draw to you:

“Once you use a flash, you’re bringing a lot of attention to the event, especially in twilight, but even in the sunlight. A flash is an invasive, aggressive kind of assault.”

Mark Cohen also struggled for a while shooting with a flash:

“My pictures are not like Cartier-Bresson, although he was a tremendous influence. It took me a while to think, “It’s okay to take flash-pictures.” Then I figured out a technique where I work inside this very short zone with a small flash.

Furthermore, he explains why he ended up being unapologetic about the way he shot (with a flash and at a close proximity with a wide-angle lens):

“Well, I was making art so I suppose I had license. That’s how I felt. Nobody was getting assaulted really; nobody was getting hurt. The intrusion was to make something much more exciting and new than sneaking a picture on a subway, like those buttonhole Walker Evans pictures or the Helen Levitt pictures. This is a whole different level of observation.”

Cohen expands on the type of energy that a flash adds to his images, and discusses the technical reasons why he likes to use a flash:

“It sets up a formal look, or what I think of a formal value in the picture where your subject is highlighted and the background is dark. But the main reason I used flash was that it gives you a zone from 2 to 8 feet and you don’t have to focus, and you don’t have to worry about the subject being blurred either, because the flash is a thousandth of a second. So, you get very sharp and clear pictures of your subject.”

Takeaway point:

When you are shooting street photography with a certain technique (with a flash, without a flash, far away with a telephoto, close with a wide-angle, etc) don’t do it for the sake of it. Think about what you are trying to accomplish through your images. Don’t shoot a technique for the sake of it. Rather, think about what you are trying to say with your photography with the technique.

For example, when I first started shooting with a flash after being inspired by Bruce Gilden— I just shot with a flash for the novelty. Not only that, but as I became more popular for shooting with a flash– I felt that I had to keep shooting with a flash to show people that I had “balls” and to keep up this persona of a street photographer who uses a flash.

But over time, I realized that this became quiet vacuous in itself. I then started to ask myself: why did I really shoot with a flash? Was it for the attention or for something deeper and more meaningful?

I started to think about it more deeply– and I discovered the reason I really enjoyed using a flash was because of the surrealism it brought to my images. I’m quite interested in making my images seem other-worldly. Not only that, but using a flash when the light is flat really helps the subject pop out from the background– bringing more attention and focus to the subject. Also now that I’m shooting color film, using a flash saturates the colors and makes them look lovely.

I would say if you have never shot with a flash– don’t feel that you have to in order to “prove” to others how courageous you are. It is a great technique when you are shooting in the shade or even mid-day, to get a proper exposure of your subject with a surreal look. Also if you are shooting film, it is very difficult to shoot at night without a flash (if you are using a slower film).

If you shoot with a digital camera, I can recommend just to use “P” mode and use the built-in flash on the camera (or a pop-up flash). If not, you can just use a simple on-camera flash and use TTL or any other automatic setting.

If you want more technical guidance on how to shoot with a flash manually (especially with a rangefinder)– you can read this great guide by Charlie Kirk here: Flash and Street Photography, a guide.

4. On having subjects pose for you

Even though a lot of Cohen’s images seem obtrusive and that he employs a “hit and run” style– he also has images where he gains consent from his subjects, and has them pose for him. He expands:

“Some of the pictures are not quite as hit-and-run as others. There is a picture of a kid holding a football. His head is cut off and it’s just his bare chest and his thin arm holding this 1950s looking football. This is an incredibly strange, sociological picture. The kid is posing for me, but I don’t make a picture with his head in it, just the bare chest and the football. I don’t remember what I thought at the time, but this is how I went about making pictures. I would make thousands of pictures and print hundreds of them.”

He shares another story of when he took a close-up of someone’s teeth:

“Those are a woman’s teeth. I knew this woman and she was laughing. I said, ‘Let me take a picture of your teeth.’ You can take the wide-angle lens at f16 and put it inches away from her mouth to take that picture. I don’t think that there’s a flash.”

Takeaway point:

Don’t always feel that your images have to be candid. Almost all of the famous street photographers in history have at least one image in their portfolio which is posed or shot with consent. Even Henri Cartier-Bresson (who is the master of shooting candidly) has photos take with consent from his subjects. Other notable examples of street photographers who interacted with their subjects and gained consent include William Klein, Diane Arbus, and even Bruce Gilden.

5. On negative reactions

I think one of the biggest fears that many of us have in street photography is how people will react to you. If you have seen videos of Mark Cohen shooting without the viewfinder or Bruce Gilden shooting in the streets with a flash you might think to yourself: he will probably get punched in the face sooner or later.

In an interview with Mark Cohen- the interviewer asks Cohen if people ever react violently to him photographing them. Cohen responds:

“A lot of times I had trouble with the cops, because if you walk into somebody’s yard and start taking pictures of a rope that’s sitting there, they’ll call the police. And if you photograph a young child and his mother sees you through the window, they get really excited.”

Cohen explains what happens when police come:

“Half of the time I could explain myself. I had all these different stories. I was driven out of Scranton a couple of times when the cops picked me up taking pictures there. They would follow me out of town. Other times someone would take down my license plate after I got in the car, and the police would show up at my house. Once a guy actually managed to track my plate number himself, and he showed up to my house. He was very belligerent because he felt like I had victimized his wife in some way when I took her picture. All kinds of things happened.”

But in terms of anything truly serious happening (getting punched in the face, getting his camera smashed, etc) never happened. The interviewer asks: “Nothing serious ever came of any of them?” Cohen responds by saying: “Basically not.”

Takeaway point:

In street photography it is inevitable you will piss someone off sooner or later. Regardless of if you’re shooting from a distance with a 50mm lens, or if you’re shooting closely with a wide-angle lens and a flash. Granted, if you’re shooting with a flash at a close proximity– you will draw a lot of attention to yourself.

Cohen shares how he has gotten in trouble with the police or with people becoming upset. However at the end of the day, he is shooting not to piss people off– but to create art, and to create sociologically powerful images.

Personally I shoot almost all of my photos of strangers with a flash– and I have gotten many negative reactions. However the worst that ever happens is that people threaten to call the cops (or actually call the cops), yell at me, threaten to break my camera, etc. But nobody has ever physically assaulted me where I felt like my life was in danger. I probably have gotten more injuries playing tennis than shooting street photography.

My practical tip is when you’re shooting on the streets, expect people to become upset. After all, it is a very strange thing to take photos of strangers without their permission. Not only that, but you will eventually piss somebody off.

If someone does get upset at you, be calm about it and explain that you’re a street photographer and you didn’t mean to upset them. It is also a good idea carrying around business cards, or a small portfolio of your work (in prints, iPad, or on your phone) to show people that you mean no harm. That you aren’t a pedophile or some creep.

It isn’t pleasant getting yelled at, ostracized, or threatened by strangers. But I think we need to accept that is a price we have to pay to create our art.

6. On discovering yourself through photography

I think one of the most beautiful things about street photography is the ability to explore ourselves through our work. Mark Cohen shares his personal experiences shooting on the streets and putting together “Grim Street“:

“[On the book] These are my favorites. They’re selected carefully, but the book is not about anything. Except that if you keep photographing in the same place, you start to find out something about yourself.“

Cohen also talks about taking photos while traveling as a means of self-exploration:

“Travel pictures are different. But I went to Mexico City ten times to take pictures, just to see how those picture would look compared to what I made in Wilkes-Barre. And they are the same. They’re not quite like the pictures I made in Wilkes-Barre, but I could have made them in Binghamton or Rochester or Elmira.

But at the end of the day, the photos he makes of a place isn’t of the place (or its inhabitants). Rather, it is about himself:

“My pictures are not about Wilkes-Barre. They’re about an artist who is making pictures without a define emotive. There is nevertheless something sociological. You see broken fences. You don’t see any swimming pools and they don’t have any L.A. glamour about them. We’re on the underside of town. I was trying to do Grim Street without our saying “Wilkes-Barre” throughout the whole book if I could get away with that. This is about something else.“

Takeaway point:

When you are out shooting on the streets, know that you are creating images that reflect yourself– and how you see the world. I know a lot of people who also see street photography as a sort of “therapy.” Personally as well, there is nothing more comforting and soothing from walking the streets, exploring, talking to strangers, and taking photos.

Through your images– really challenge yourself to discover who you are. Do you see the world in a positive light? A negative light? What do your photos show that you are naturally interested in? People? Signs? The street itself? Composition? Form? Who are you as a person– and how does your photography reflect that?

9. On shooting without a viewfinder

There is generally a stigma in the street photography against “shooting from the hip” or taking photos without using a viewfinder. Why is this?

To better explain, let me use myself as an example. When I started to shoot street photography, I shot from the hip (putting my camera at waist level, and pretending not to take a photo– when I actually was) quite a bit. I did this for several reasons.

First of all, I didn’t want to be noticed by others that I was taking photos. I didn’t want people to catch me taking their photograph– and perhaps getting upset, belligerent, or confronting me. I also didn’t want to bother people, and I thought by shooting from the hip– I would annoy fewer people.

Secondly, I didn’t want to “disrupt the moment.” I thought that by bringing my camera to my eye, people would notice it too much– which would change the characteristic of the scene I saw.

However after about half a year of shooting from the hip– I discovered many problems.

First of all, almost all of my photos were skewed. They all had this weird diagonal tilt when shooting from the hip.

Secondly, my compositions were really loose and poorly framed. I would often chop off heads, and other body parts– or have too much negative space.

Thirdly, it prevented me from building up my confidence in the streets. When I started to use the viewfinder more, it gave me more courage and confidence. I discovered shooting from the hip as a detriment and a barrier to building my confidence in street photography.

Now I never shoot from the hip, but occasionally I take photos without using my viewfinder if I need to put my camera on the ground and shoot from a super low angle, or when holding my camera high up to get a very high perspective.

Interestingly enough, when you see videos of Mark Cohen shooting in the streets– he doesn’t use his viewfinder. However this is different from “shooting from the hip.” What is the difference?

I think when you’re shooting from the hip– you’re trying to be sneaky and try not to have other people notice that you’re taking a photo. However shooting without a viewfinder is a bit different. People can still notice you taking their photo if you don’t use a viewfinder.

In Mark Cohen’s case, he shot quite aggressively and used a flash– so it was quite obvious that he shot without a viewfinder.

I think the reason he didn’t use a viewfinder was it helped him get more edgy compositions by shooting from super low angles (like photos he takes of shoes, knees, and feet).

Not only that, but because he was shooting extremely wide (21-28mm) he probably couldn’t have used the viewfinder anyways at close distances. This is because of parallax error.

For those of you unfamiliar with parallax error, when you are shooting with a rangefinder your framing becomes very inaccurate when you are closer than around 1 meter. And a lot of Cohen’s shots were shot at minimum focusing distance (with a super wide lens). Meaning that using a viewfinder at that point would be pointless. He needed his camera to be level and head-on to his subjects to get a better frame.

Cohen explains a bit of how he shot without using a viewfinder:

“I wasn’t looking through the viewfinder at this point anyway. In the early seventies I was making pictures with 21 and 28mm lenses that just enlarged the depth of field incredibly, and the little flash would carry out 3 to 5 feet. So in that small space, like in the knee picture of the bubble gum picture, I’m only a foot or two away from these people. And I learned to hold the camera very levels the pictures didn’t look like wild wide-angle pictures.”

Cohen shot without using the viewfinder so long that he was able to take photos while keeping his camera straight. And I think he shot without a viewfinder less of the fact that he didn’t want to be noticed– more for compositional and framing reasons. He probably shot so much with his 21mm and 28mm that he knew his framing relatively accurately.

To watch him in action, you can see him shooting street photography on YouTube here. Or you can watch the embedded video below (and skip to 30 seconds in):

Takeaway point:

I generally discourage street photographers starting off to shoot from the hip. Why is that? Once again, your hands will never frame as accurately as your eye– and I find shooting from the hip to be a barrier to building your confidence when shooting on the streets.

However of course there are exceptions. For example, if I were in North Korea and I didn’t want to be noticed taking a photo I might shoot from the hip. If you live in a place any safer than North Korea– I recommend not to shoot from the hip.

However shooting without a viewfinder is a totally different issue. A lot of cameras out there now don’t have viewfinders. Especially a lot of micro 4/3rd and compact cameras (or even smartphones). In those cases, the great thing about not using a viewfinder is the fact that you can get more edgy compositions by changing your perspective (shooting super low-angle, or super high-angle). Even if you’re shooting with a DSLR in which you can’t frame with the LCD screen, putting your camera on the ground or high in the air can help you create more interesting images.

But in the end of the day, shoot in a way that makes you the most comfortable. There is no one “right” way to shoot street photography in terms of technique. Mark Cohen shoots quite unorthodoxly and he made it work for him.

10. Harness spontaneity

One of the most beautiful things about street photography is a sense of spontaneity. You never really know what will happen in your photo until you click the shutter. Some of Cohen’s best photos have a great deal of spontaneity in them. He explains how he is able to harness his subconscious when shooting on the streets:

“There’s no complicity in my work. I don’t know anybody. Look at that kid with the homemade tattoo on his arm. I try to just lift things like that off as I go by. Sometimes I stop to talk to people, but most of the time I keep on going. And since I often don’t look through the viewfinder and I use this quick flash, I don’t know what the pictures look like until I develop the film. Then I have these pictures that are made unconsciously and spontaneously. I’m able to make a good composition and keep a formal quality, but above all there is some other kind of mental operation going on that is not completely defined yet.

Sometimes when you’re taking a photo– you can’t even expect the small random happenings which make the photo special. For example, in one of his most famous photos with a hand and bubble gum he explains:

“I didn’t see that kid’s hand up when I took the shot, and that makes the picture. The girl’s blowing the bubble, and I’m just holding the camera level in the right place in this little event that’s happening in a very, very short span of time.”

Cohen also explains how a lot of his street photography was mood-driven, in terms of where he would decide to shoot. Even when putting together his 30+ years body of work, he never really had a plan:

“[Grim Street] is about my hometown set of pictures. This is my home, so if it’s a cloudy day, I know which alley to go down. If it’s a sunny day, I know I want to go over where there’s this kind of action and where I can find that kind of backyard. A lot of this is mood driven, but I don’t exactly know where the motive and inspiration to take pictures comes from. So it’s very spontaneous work; there’s not a lot really to plan. The plan is just to print these hundred pictures. But this work is also how far I’ve gone with my limitations after thirty years or so.”

Takeaway point:

I am a big advocate for working on projects— and having some sort of goal or mission when you’re shooting. However at the same time– some of the best work you can create can be from this free-flowing style that Cohen adapts.

He lets his emotions lead him to where he wants to shoot, and he didn’t really have a plan in terms of how to put together his book. He just shot the best photos he could during his 30+ years shooting in his hometown, and decided to put together his best images after that period.

Personally what I do when I’m out shooting is that I am in a project-mindset, but I allow spontaneity and randomness to add flexibility to my work and shooting. You can adopt the same approach, or just do it totally based on mood and your emotions. Do what makes you happy. Also realize nothing in street photography (really) ever goes according to plan.

11. On putting together “Grim Street”

One of the things that I am very interested as a photographer is how photographers put together their books. Mark Cohen shares a bit of his inspirations of putting together “Grim Street” and what mood he is trying to convey through his images:

“I’m making pictures in this one area. But there are these odd, eerie impulses, maybe from a lot of unconscious regions, influencing how I select people. And that’s why the book is called Grim Street.”

His guiding principles to organizing “Grim Street” is as follows:

“I’ve wanted to make a book for a long time. I made two hundred of the glossy reproduction prints and then eventually cut them in half. So, in this unconscious, uncurated way I put together what I basically think is my best work. They’re going in the book chronologically, because they all have dates on them. I don’t know exactly how it’s going to come out, but I think it’s going to be pretty good.”

Takeaway point:

I think titles are important to books– as they set the mood and how you interpret the images. Because Cohen titled the book: “Grim Street” it paints the picture of the other-wordliness of his images.

Interestingly enough, Cohen put together his photos in his book in a very unconventional way: chronologically. Most photographers I know generally sequence based on emotion, mood, and the flow. However Cohen embraced his unconscious when it came to choosing his best images– and just sequenced his photos according to when he shot them. And strangely enough– it works. The photos in the book have a lovely flow to them. Perhaps this is because as time goes on, his style of shooting changes– which adds to the flow? I’m not sure– but it just shows that there isn’t ever one “right” way to put together a book.

So when you are putting together your own book or body of work– no that there are no “rules.” There are certainly guidelines and suggestions out there (like the ones I provide on this blog)– but at the end of the day, do what makes sense to you and what makes you happy. You can edit or sequence your work in a more logical, systematic way– or you can embrace your unconscious. Or perhaps a combination of both?

12. On evolving as a photographer

Many photographers (Mark Cohen as well) evolve over time. Evolve in terms of how they shoot, what they shoot, and why they shoot.

Mark Cohen shares how his style of shooting street photography has changed and evolved over the years:

“[Over time] I got farther and father away. I started with a 21mm lens, then I moved to a 28m and then a 35mm, and now I’m using a fifty; mainly because I would get into situations where I could be arrested, or the police would come. People would sometimes get very suspicious and agitated, and I had all kinds of trouble because I was never part of a newspaper so I could’t say that I was on assignment. I’m just this guy doing this. And I fugue, well, I have a right to do this. But, even in the media today, it is really not okay for some guy to get close to some little kid and take his picture in his backyard. You can’t do that anymore because there’s a sexual suspicion that develops. You can’t just explain to some kid’s mother that it’s really this kid’s beautiful ankle that I wanted to take a picture of by this puddle. So then I started using a 50mm lens, and now my work is much different than it was in the 70’s.”

Takeaway point:

Unfortunately the reality is that a lot of people nowadays are more suspicious of street photographers than they were in the past. A few decades ago, nobody would care if you took photos of their kids. But now with the media and social media– people are afraid that you might be a pedophile or something like that.

Cohen had to change and evolve his style in street photography because of how others changed. So he has changed from using a 21mm, to a 28mm, to a 35mm, and to a 50mm now. I haven’t seen any of his newer work with a 50mm, but I am sure that he has made it work for him.

Personally I never have any issues taking photos of children– as I try to do it in a non-sneaky (or creepy) way (I generally smile and wave at the kids, and interact with the parents when taking photos). Or I will ask permission from the parents if it is okay that I take photos of their kid.

But anyways, I think to change either your technique, subject matter, or style in street photography is totally normal over time. Your tastes in photography will probably change over the years. You might even grow out of “street photography” as Lee Friedlander did– and might shoot flowers or trees (Friedlander made a book on trees).

I would say for every photographer in order to evolve and push forward to the next level– you need to constantly reinvent yourself over time. For example, Andy Warhol started off as a successful commercial artist– but it wasn’t until he started making art out of Brillo boxes and Cambell’s soup did he gain fame. The same goes with Pablo Picasso– he did lots of traditional art starting off, but he never achieved acclaim until he started to make his more abstract art.

I have personally gone through a lot of evolution in my street photography as well. I started off shooting black and white like Henri Cartier-Bresson (using a 50mm from a distance) by looking for interesting backgrounds, and waiting for the right person to enter the scene. Then I started to shoot street photography like Bruce Gilden– using a 24mm lens and getting close to my subjects and using a flash. Nowadays I enjoy shooting more urban landscapes (in color)– similarly to Lee Friedlander, Stephen Shore, William Eggleston, and Joel Sternfeld. I also made the shift from shooting in digital to film now.

So don’t feel that you have to remain “faithful” to your own style and approach for a very long time. Try to stay consistent in terms of your process and aesthetic within a certain project, but as you work on new projects over time– try to switch it up. Keep exploring, experiment, and push your photography to the limits.

13. On seeing

In street photography the two most important things are your eyes and your feet. Especially your eyes. You need to see if you want to make great photos.

Mark Cohen explains the importance of seeing in street photography:

“Before you start with the camera, you have to see something. A lot of times I see things while I’m driving the car, and well, I’m going to miss that picture. But when I’m walking on the street, I see something and go after it. I pick up the camera, keep it level, get the flash out, and walk toward the subject. And this little girl is walking in the street and she has this white sock and she’s with her mother… and I stopped the car and went after that subject and took a flash-picture of her sock and her leg. And in that background and that ambient light there’s wonderful, abstract kind of Minor White picture. There are two layers of picture going on.”

Takeaway point:

I think it is important to always be looking for pictures. After all of these years of shooting– I almost have a little black box that frames my world. I see almost everything as potential images. By having this frame constantly in my mind– it changes how I see the world, but also gives me better vision to make photos.

So first of all, I always recommend you to have your camera with you at all times. Then of course, always be looking for potential images. And if you see a good potential image, don’t hesitate. Go after it. Take a photograph, rather than regretting not having taken it.

14. On his drive

Mark Cohen has taken photos in his small town for over 30 years. Very few photographers have that grit and tenacity. What drove him to keep shooting on the streets? Cohen says it is the thrill of trying to create new types of images:

“When you feel like you’re making pictures– the most important is to make new pictures. The pictures you already took– you already took those pictures. My main drive is to do something new– to make some new kind of picture.”

Takeaway point:

This point goes well with the idea of evolving as a photographer. Don’t just keep shooting the same images over and over again. Rather, try to push yourself to create new images. Images that are unique to yourself. Images that are unique to others.

We live in a society where we are bombarded by thousands of images from all around the web. Do you really want to continue to add to the glut of cliche images that we have already seen hundreds of times? Or do you want to create unique images that the world (or yourself) hasn’t seen before?

So let your passion, ambition– and love of street photography continue to push you to create beautiful (or not so beautiful) images of the world. But the most important thing is do it in your way. Your unique way of seeing the world– that is different from others.

Conclusion

Mark Cohen is living proof that you don’t need to live in some super fancy city to make interesting photos. He shot street photography for over 30 years in his small town– and it was his drive of making new photos and pushing his limits that drove him. He wasn’t even quite sure what his goal was but street photography was something that he had to do. It was like an itch that needed to be scratched. So let us not make excuses in our own street photography (in terms of where we live or our circumstances). Let’s just go out there and do it like Cohen.

Mark Cohen Biography

This biography of Mark Cohen was from his exhibition in Paris at Le Bal:

Mark Cohen was born in 1943 in Wilkes-Barre, a small Pennsylvania mining town. A figure of the street photography genre which dominated American photography in the early 1970s, he is also the inventor of a distinctive photographic language, marked by a fleeting arrangement of lines and, at the same time, an instinctive grasp of the organic, sculptural quality of forms. Two photographs hang opposite each other in his studio: one from Henri Cartier-Bresson’s surrealist period and another by Aaron Siskind. The elegant geometry of one and the dry plenitude of the other transpire in the work of Mark Cohen, which John Szarkowski showed at the MoMA as of 1973.

Over the past 40 years Mark Cohen has walked the length and breadth of the streets in and around his hometown, seizing – or rather extracting – fragments of gestures, postures and bodies. In his photos we see headless torsos, smiling children, willing subjects yet still frighteningly vulnerable, thinly sketched limbs and coats worn like protective cloaks. Thus Mark Cohen slices and sculpts the very thick of the world to impose, in successive touches, a Kafkaesque vision, ruthless and poetic, of an environment that encompasses him. A vision from within.

This remarkable body of work – Cohen rarely uses the viewfinder, holding the camera at arm’s length – is rooted in impulsions that last just fractions of a second. A disconcerting strangeness emanates from his subjects, some caught in the dazzle of the flash. Bodies seem uncomfortable, threatened, lost, grinning too wildly or reduced to their erotic dimension. Ordinary objects appear isolated, mysterious, sinister. The decline of this small mining town is right there, in its yards, at its bus stops, on its porches, but Mark Cohen’s intentions are anything but documentary. Repetitive to the verge of obsession, he has no idea what brought him there or what he hopes to find. Rather he is driven by the beauty of a chance encounter, by the torments or delights he detects in another’s substance.

There is, in the brutality of his gaze, a rawness and a nervous energy, an ambivalence and a grace through which the making of a photo becomes the expression of a revelation.

Videos

Below are two excellent videos on YouTube in which Cohen speaks about his work– and you see footage of him shooting on the streets:

Mark Cohen: In Action

Mark Cohen Interview and on the Streets

Books

1. Mark Cohen: Grim Street

I highly recommend picking up “Grim Street” and seeing Cohen’s incredible body of work. The book is currently out-of-print, but you can find some great priced used copies on Amazon. Most of the excerpts I used in this article are from the interviews with Cohen included in the book.

You can also pick up a signed copy directly from Powerhouse here.

2. Mark Cohen: True Color

“True Color” is Mark Cohen’s collection of color street photographs. Very interesting to look at as well– not as strong as “Grim Street“, but if you want to explore some his color work it is definitely worth having!

3. Mark Cohen: Dark Knees

“Dark Knees” is Cohen’s newest book, which includes newer images (not seen in Grim Street) — for a combined 40 years of his street photography in his hometown. I’m sure it will be an incredible book– and I just pre-ordered mine. Don’t miss out!

You can also see a review of Dark Knees on Lensculture here.