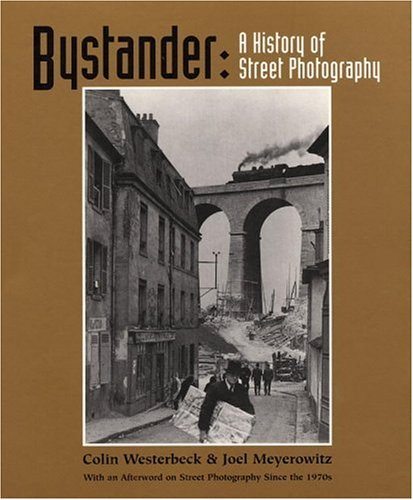

There are very few books written on the history of street photography. However, the best book that I know: “Bystander: A History of Photography” is superb. The book was co-authored by photography curator and historian Colin Westerbeck and the legendary street photographer Joel Meyerowitz. The two collaborated for many years on the book, with Westerbeck doing most of the writing and Meyerowitz giving guidance and helping edit images for the book.

I picked up my copy a few years ago, and was amazed to see how in-depth and expansive it was on the history of street photography. I used it as a reference for an online course I taught on street photography at UC Riverside Extension in 2011, and learned many insights from the book.

I wanted to write this article to share some of my personal insights which I learned from the book and the history of street photography. I hope you enjoy it. Also if you see any typos, grammatical errors, or unclear points- please leave a comment below.

Considering this is a long article (31 pages long), I consider you to either save it to Pocket or to Instapaper and read it in bits and chunks. You can also download a .doc file of it, or a PDF of the article.

How I met Colin Westerbeck

Before I get started, I want to share an interesting anecdote of how I actually met Colin Westerbeck by chance. The program director for UC Riverside’s online program was at a dinner party, and randomly met Colin Westerbeck who mentioned that he was interested in photography.

She then mentioned to him that I was teaching a course on street photography. She then was surprised when Westerbeck told her that he wrote a book on the history of street photography (which I was using to create the course).

I met Westerbeck, he gave me some great guidance on my own street photography, signed my copy of Bystander, and helped me edit the final exhibition for the students of my UC Riverside class.

I can personally vouch that he is extremely knowledgeable about street photography, and that he is a very generous human being as well.

The history of street photography

I have never been a fan of history (from bad memories of rote memorization in school). However I am starting to realize over time the importance of history in our everyday lives. Especially when it comes to the history of street photography.

Street photography is a tradition that dates back to the invention of photography. The invention of photography in the early 20th century coincided with the urbanization and globalization of the world.

Therefore the first photographs ever taken were generally done in the streets. So the start of photography was the start of street photography.

A new chapter in the history of street photography

I think there is a new chapter unfolding in the history of street photography. The technology that our cameras have would have been unimaginable even a half century ago. With our full-frame digital cameras, we can now shoot up to ISO 12,800 (with little discernible noise) and we can take thousands of photographs in just a day. Compare that to the ISO 25 film that they used to use back in the day, and the long process of developing and printing photos.

Street photography also used to be a solitary activity, with few photographers collaborating and sharing their prints with one another.

Now with social media sites like Facebook, Flickr, 500px, Google+, and many others– everyone has the opportunity to share their images with the world. And with that, tons of great work is being produced from every corner of the globe. Not only that, but many talented street photographers are now being discovered and appreciated.

What contemporary street photographers can learn from the past

I personally am a fan of new technologies and ways for us to connect. But at the same time, I appreciate and respect tradition. I think for us street photographers in the 21st century, we can learn much about street photography from our past and the great photographers that came before us.

I feel this is especially important when it comes to discussions in street photography about approach, style, aesthetics, and equipment. Many arguments we have nowadays seem to be quite recent and new (think about arguments in street photography over equipment, lenses, approach, style, aesthetics, etc). But in reality, many of these arguments have been going on for decades – if not for over a century.

For example, many photographers decry the use of image-editing software like Lightroom and Photoshop when it comes to post-processing their images. But photographers have been manipulating their negatives and prints since the beginning of photography.

Photographers argue about the use of flash in street photography, but it has been used by a photographer named Jacob Riis (flash powder) since 1887 (in dark bars at night). Another argument I see made a lot is about being seen vs being discrete in street photography. Although some street photographers feast on being hidden and discrete (think Henri Cartier-Bresson), many other photographers were much more straight-forward when approaching their subjects (think Diane Arbus or William Klein).

Many photographers argue about different focal lengths in street photography (about which is the “proper” one). Although I am personally a fan of wide-angle lenses, street photographers have been using lenses from 21mm-200mm in the course of history.

Disclaimers for this article

A warning: this post is not comprehensive nor does it try to be. Bystander is over 400 pages long, and there is no way for me to talk about every single photographer in the history of street photography. I was very selective in choosing certain quotes and excepts from the book which I found interesting which could hopefully give you, the reader, more insight when it comes to street photography.

I also purposefully left out many influential street photographers (Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank, and many others) as I feel that I have done comprehensive articles on them already. As for other influential street photographers I have left out, it was either because I personally don’t find their work interesting enough or I plan to write a more personalized in-depth article about them in the future.

The article is over 14,000 words which my word processor says will amount to about 1 hour and 30 minutes of reading. So don’t feel obliged to read it all in one sitting. Pick out the parts that interest you, skip around, and I hope you find the history of street photography to be incredibly insightful. I know I have.

To keep this article structured, I have organized it the following way:

- a) History/Definitions for Street Photography

- b) Technical insights for the History of Street Photography

- c) The Use of Different Cameras/Equipment for Street Photography

Some of the sections are more in-depth than the others, which is a personal bias I had when compiling/writing this article.

a) History/Definitions for Street Photography

1. The term for “street photographer” evolves over time

One of the most common (and frustrating) arguments that goes around the web is “what is street photography?” and “what isn’t street photography?” Street photographers waste time discussing definitions rather than going out and shooting.

One of the issues of what is a street photograph/what isn’t a street photograph is that the definition of a “street photographer” evolves over time.

For example, in the early 20th century the term for “street photographer” was someone who took your photo in the street for a fee. An excerpt from Bystander:

“To most people a street photographer is someone in times square or Piccadilly circus who will take your picture for a fee and send you the print later (or, since the adoption of the polaroid by such vendors, give it to you right on the spot).

You don’t see too many of those street photographers anymore, although you will spot some in tourist traps around the world. Some even pretend to take your photo for free, and then demand that you pay them after (the good old “bait and switch” technique).

Now we commonly understand a “street photographer” as someone who goes out to public places and takes photos (usually candidly). But there are now many debates whether or not street photography even needs to be candid or not. After all, some of the most famous images by Diane Arbus (grenade boy), Cartier-Bresson (the photo of the transvestite and two women in Spain), and William Klein (kid with a gun) weren’t candid– but with the subjects’ consent.

Even Colin Westerbeck admits that not all street photographersin history shot candidly:

In at least one prominent instance, a photographer discussed in this book – Weegee—did begin his career by playing that trade and from John Thomson to Manuel Alvarez Bravo to Diane Arbus, there are certainly others here who made a practice of soliciting subjects for impromptu portraits done on the street.

But Westerbeck still holds to the point that he feels that for the most part, street photography is done candidly:

For the most part, however, the photographers discussed in these pages have tried to work without being noticed by their subjects. They have taken pictures of people who are going abut their business unaware of the photographer’s presence. They have made candid pictures of everyday life in the street. That, at its core, is what street photography is.

But what does Westerbeck think differentiates street photography from others forms of photography– and what makes it unique? This is where things become a bit grey:

[Street photography] is kind of photography that tells us something crucial about the nature of the medium as a whole, about what is unique to the imagery that it produces. The combination of this instrument, a camera, and this subject matter, the street, yields a type of picture that is idiosyncratic to photography in a way that other formal portraits, pictoral landscapes, and other kinds of genre scenes are not.

Therefore you can see from the excerpts above that the term “street photographer” has evolved from a peddler taking photos of strangers on the streets (for a fee) to a flaneur taking “candid photos of everyday life in the streets”.

But now we see lots of great street photography done outside of the streets– in malls, parks, and even beaches. Mostly public places. And like in the past, not all street photography is done candidly.

Takeaway point: Personally, my own definition of street photography changes and evolves over time as well. So realize as time (and history) progresses– the type of street photographs people are going to take (and where they take them) are going to change/evolve. So don’t worry so much about what street photography is/isn’t, but go out and strive to take what you think is street photography.

2. Does street photography have to have people in it?

Piggybacking off the previous point, does street photography even need to have people in it? Well in the early days of photography (when there were bulky large-format cameras) it was hard to have people stand still for long enough to take their photograph. Not only that, but it was probably impossible to do it candidly as well.

One of the earliest pioneers of street photography was Eugene Atget, who photographed the streets of Paris (mostly of architecture). Some of his photos have people in it, but most don’t. Westerbeck mentions this in Bystander:

While stop-action images of people are bound to figure prominently in any collection of street photographs, this book also contains many pictures in which there are no people at all.

The most salient examples are to be found among the pictures of Eugene Atget. Yet even he was, through implication and inference, trying to show us life on the street. Suggesting presence in the midst of absence, he was attempting to reveal the life of the street as it inhered in the setting itself. Like every other practitioner of the genre, he wandered the streets with his camera, looking what would today be called photo opportunities. More important, he was like every other street photographer in his readiness to respond to errant details, chance juxtapostions, odd non sequiturs, peculiarities of scale, the quirkiness of life on the street.

But if Atget shot mostly architecture (most without people), how can we consider him a street photographer? This is a question that has puzzled me and many other street photographers I know. Westerbeck explains:

Atget was chief among photography’s scenic designers of this type. Even when he was functioning as a documenter of architecture, which was much of the time, he was capable of making images that would be inspiring to other street photographers later.

The difference between his pictures of buildings and the conventional ones done by his contemporaries and predecessors in the field is that theirs idealize the architecture, removing it as much as possible from any particular time and place, while his always insinuate the actual streets of Paris where his subjects were found.”

Westerbeck essentially says that Atget’s work focused more on the “actual streets of Paris” rather than just on the architecture.

Takeaway point: Does your street photographs have to have people in them? If we can claim Eugene Atget as one of the earliest street photographers, I think we can confidently claim that street photographs don’t have to have people in them.

Lately I have been shooting a lot of what I like to call “still life street photography”. It is essentially photos without people in them, but still have some feeling of humanity through a subject we can empathize with. Whether it be a lonely parking cone, a piece of bacon randomly sitting in the middle of the street, or a discarded stuffed animal.

So don’t just shoot street photos of people, feel free to also do scenes or objects (that don’t have people in it).

3. What was the first book done on street photography?

According to Bystander, the first book done on street photography was in 1877 by John Thomson, a Scottish photographer. He titled the book: “Street life in London”.

Interesting to note that most of the subjects in the photographs posed for him, as the “collodion” process he used (which emphasized sharpness) needed a very slow film speed. So his subjects had to stand still for a very long time, which prevented him from taking candid photos.

Takeaway point: I find it interesting how technology influences how we shoot street photography. In the early days of photography, the film was so slow (and cameras large and bulky) that it was difficult (if not impossible) in most situations to photograph people in public candidly. But as technology evolved to accommodate nimbler cameras and better speed films, the type of street photographs people started taking started evolving as well.

This makes me think much about cameras that can shoot nearly in pitch dark, with an ISO of 12,800. Or cameras that have swivel-screens that allow you to shoot from a really low angle, candidly.

So realize that the technology of the camera you are using will change your output, and don’t get stuck into the mantra of thinking the old is necessarily better than the new.

4. On preserving history

One of the things I love most about street photography is how it can preserve history and how places change over time. One great early street photographer who realized the early potential for capturing history though his camera was Samuel Coulthurst, who shot from the late 1800’s:

Samuel Coulthurst, photographed the salford market disguised as a rag and bone man. During his decade long tenure, he built up a collection of more than two hundred views, about a quarter of which he made himself.

One of the most insightful things I then read was how he realized that the photographs that he was capturing at the present moment (ordinary photos during his time) would extraordinary and could be used as historical documents in the future:

His appetite for street photography still unsated, Coulthurst also indulged it on trips around Britain and to the continent. He was very aware that he was recording something “for future reference.” Writing in 1895, he took the position that “our street trades, such as the organ grinder, street artist, hawker, scissor grinder, etc., will soon be objects of the past, and pictures of them will be of as much value.. as pictures of old houses.”

Coulthurst realized that during his time the social landscape was quickly changing and evolving, and that if he didn’t document the people on the streets– people in the future may never have even known they existed.

Not only that, but Coulthurst also made a call to his fellow street photographers to start documenting their present day as well:

Five years before Coulthurst issued his own call fro greater emphasis on street photography, a writer in the photographic report had urged amateurs everywhere to “endeavor to secure street life in your own town. All things change in the course of time, and someday such pictures may become valuable.” (said in 1890)

He made the statement for his fellow amateurs to capture things that may one day “…become valuable”. Realize that he made this statement in 1890.

Takeaway point: As I write this, it is the year 2013 and our world is inundated with technology our forefathers would have never dreamed of. Phones that are thinner than a piece of toast and can access the internet at lightning-high speeds, cars that drive on electricity only, and skyscrapers that tower into the heavens.

Of course, we are all used to these sights and they are quite ordinary to us.

However realize that we are living in an incredible day and age, and the photos that we take today will be valuable records of our time 100 years from now. We often hear of stories of photographs taken from several decades ago being uncovered– and we marvel at the sense of nostalgia it brings back for us.

So I guess I have a similar call-to-action as Coulthurst: Photograph your daily surroundings, day-to-day lives, and societies passionately. Know that one day your future grandchildren or grand-grand-children will look at your photos and marvel at the history you captured.

Philosophy of Street Photography

1. On making “tough” street photographs

I think one of the biggest questions that always goes through my mind is: “what makes a good or a great street photograph?. Joel Meyerowitz, one of the heavyweights in the history of street photography tells us the importance of making “tough photographs” in an interview with Colin Westerbeck:

Colin Westerbeck: I remember hearing Garry Winogrand and the rest of you often calling pictures “tough” or “beautiful.” Why was “tough” such a key word for you?

Joel Meyerowitz: “I think that as long as theres photography, there’ll always be people trying to make street pictures – tough pictures of the kind that Garry and Tod and I were inspired to make twenty five years ago. “Tough” was a term we used to use a lot. Stark, spare, hard, demanding, tough: these were values that we applied to the act of making photographs.

‘Tough’ meant the image was uncompromising. It was something made out of your guts, out of your instinct, and it was unwieldy in some way, not capable of being categorized by ordinary standards. So it was tough. It was tough to like, tough to see, tough to make, tough to draw meaning from. It wasn’t what most photographs looked like. You couldn’t always address it with the familiar terms of other photographs. It was a type of picture that made you uncomfortable sometimes you didn’t quite understand it. It made you grind your teeth.

At the same time, though, you knew it was beautiful, because ‘tough’ also meant that—it meant beautiful too. If you said of a photograph, “Gee, that’s tough” or “that’s beautiful”, it meant that in the moment of making that photograph, you were beautiful. It was as if you were graced at that moment. You were in touch with the sudden appearance of beauty and were touched by its purity. That’s what made the picture tough. The two words – “tough” and “beautiful” became synonyms somehow. They were what street photography was all about.

Takeaway point: Don’t take easy street photographs. Strive to take tough street photographs.

We know what the “easy” street photographs are. Photos of street performers, the homeless, and other types of cliche images.

Go for the tough street photographs. Strive to take photos that scare you. Strive to take photos of people that can make your gut wrench. Make a photograph that the viewer looks at your photo and makes them feel what your subject feels. Try to take your photos to the next level and make them more complex (not complicated). Add layers, emotion, and form and you will make more beautiful street photographs.

2. On the importance of contact sheets

I did a lengthy post on the importance of contact sheets for street photographers– and will mention the importance here again.

As photographers, we are often more interested in looking at the final product of our efforts (the final image) rather than the process it took to get that photograph.

Henri Cartier-Bresson wasn’t very interested in looking at other photographers’ prints. In-fact, he was more interested in seeing their contact sheets. Why? Westerbeck fills us in:

Cartier-Bresson has said that the photographer himself is revealed more clearly by his contact sheets than by prints. When younger photographers ask to show him their work, it is only the contacts he wants to see. “I prefer to look at contact sheets, because there one can see the individual”

I have also read other excerpts in which Henri Cartier-Bresson would judge potential applicants to Magnum based on their contact sheets, not prints as well. It gave him a better sense of how truly talented and hard-working a photographer was than just relying on pure luck. How hard did the photographer “work the scene” to capture the image? Was the photographer efficient with their film? Or did they mindlessly click away? This can all be uncovered in a photographer’s contact sheet.

What can we learn from HCB’s own contact sheets?

On Cartier-Bresson’s own sheets, you can see the sequence of shots building toward the best picture. When he goes over them, he marks the best negatives with one to four sidebars that rate each from “maybe” to “perfect”.

Takeaway point: There is a bit of myth behind “the decisive moment.” I think many people mis-interpret the work of many famous photographers (HCB included) that they simply saw an interesting scene, clicked one frame– and moved on. That was far from the case.

Sure there were rare occasions when photographers just took one photograph of an interesting scene and got their famous images. However in most cases, the photographers would “work the scene” taking several photographs of the same scene, from different angles, perspectives, by crouching, getting closer, and using horizontal vs vertical orientations.

Contact sheets are a valuable learning tool. Learn from your own photographs by looking back at the sequences going up to your best shot. Study them closely. How conscious were you when you clicked the shutter– or did you just rapid-fire like a madman? Also was that small detail in the background from pure luck, or did you intend it?

Make sure to also study the contact sheets of the masters. I highly recommend everyone who wants to take their learning to the next level to pick up a copy of Magnum Contact Sheets. You can also read an article I wrote about what you can learn from contact sheets.

3. On being “in the flow” when shooting on the streets

One of the most important things as a street photographer is to be ready for the decisive moment and getting into the “flow” of when shooting on the streets.

So how might a street photographer look who is totally absorbed in the moment of shooting? Truman Capote writes an excerpt on his experiences seeing Henri Cartier-Bresson shooting on the streets:

“I remember once watching Cartier-Bresson at work on a street in New Orleans—dancing along the pavement like an agitated dragonfly, three Leicas swinging from straps around his neck, a fourth hugged to his eye: click-click-click (the camera seemed to be part of his own body), clicking away with a joyous intensity, a religious absorption.”

Capote wrote this except based on his memory as HCB claimed to have never carried more than two Leicas with him at a time. However Capote’s account still gives us a very vivid description of how HCB looked when he was shooting on the street. Animated, always on his toes, and shooting with a “…joyous intensity, a religious absorption.”

It sounds very similar to what people call being “in the flow” when you are so absorbed into what you are doing that you totally disregard everything else. A feeling of pure ecstasy, when you forget yourself and who you are.

Another account of HCB shooting on the street is by writer John Malcom Brinnin:

Cartier-Bresson’s “eye is polyhedral, like a flys. Focusing on one thing, he quivers in the imminence of ten others.. when theres nothing in view, he’s mute, unapproachable, humming-bird tense”

If we look at many of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photos, they have great depth and layers to them (think about his India work). When HCB was shooting on the street, he was constantly jittery– looking around for other photography opportunities. But when there was nothing to be seen, he stayed tense to wait for the next decisive moment. But why so tense? HCB explains himself:

“One must seize the moment before it passes, the fleeting gesture, the evanescent smile… that’s why I’m so nervous – its horrible for my friends

but its only by maintaining a permanent tension that I can stick to reality.”

So Henri Cartier-Bresson shares that he is always on the lookout for the “fleeting gesture” and he is a bit nervous that he may miss out on those opportunities. So keeping that constant tension is what keeps him feeling alive.

Takeaway point: I don’t think you always need to be tense and nervous as a street photographer. However as mentioned in the first excerpt it is important to get “in the zone” when you are shooting on the streets. Getting totally absorbed in the act of shooting, and not worrying about anything else.

This means turning off your phone, worrying about the stressors of everyday life. If you like to shoot with others that is great (I enjoy this myself), but if you find others to distract you when on the streets– go shoot alone. Enjoy yourself when shooting on the streets, but at the same time still stay energized and focused and try to capture those decisive moments as small as a smile, a certain look, or a certain expression someone may give with their hands.

4. On composition and juxtapositions in street photography

Street photography is hard. Not only do we need to discover interesting moments, but we need to have the speed and the clarity to capture it quickly to make a pleasing composition and structure.

We often see lots of juxtaposition playing in Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs. What does he say about his own photographs? He describes it as poetry:

“Poetry includes two elements which are suddenly in conflict—a spark between two elements.”

Takeaway point #1: When you are constructing your images, try to create some sort of tension and conflict in your images through juxtaposition. At the most basic level, you want to juxtapose at least two elements. Of course if we look at more contemporary work like that of Alex Webb, he often creates juxtapositions with several different elements.

So instead of creating photos that are just one tone, add several tones– and elements of interest to make the viewer more intrigued by your frames.

When we look at most of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, they have superb composition and geometry. What does HCB have to say about composition and creating structure in photographs? He shares below:

“Just as one can analyze the structure of a painting, so in a good photograph one can discover the same rules, the proportional mean, the square within the rectangle, the golden rule, etc. That’s why I like the rectangular dimension of the Leica negative, 24 by 36mm. I have a passion for geometry.”

But how exactly did Henri Cartier-Bresson construct his images? Did he use the “rule of thirds”, or something more complex? The secret is that his method was based on “the golden section”. Westerbeck explains:

Studied under Andre Lhote, who worked on a system for analyzing masterpieces with mathematical rigor. His method was based on the “golden section”, a progression of numbers in which each is the sum of the two preceding figures and the mean of the two on either side.

Takeaway point #2: We should treat the compositions in our photographs the same as the compositions that painters used. Not only that, but realize that a great street photograph needs strong content and strong form. Without the other the photograph fails. Most of the photos we take tend to have strong content (what we find interesting about a person or a place), but it is difficult to get a good composition.

In regards to getting better compositions, I highly recommend reading articles on composition on Adam Marelli’s site especially deconstructing the compositions of Henri Cartier-Bresson.

5. On photographing the homeless

When it comes to photographing on the street, a touchy issue is always the ethics of photographing the homeless or the destitute. Should we photograph them or not?

If we look at the history of street photography, there has been tons of street photography done on the homeless. We see photographs of the homeless by Henri Cartier-Bresson, by Walker Evans, and many others.

Ironically enough when Henri Cartier-Bresson was interviewed about the issue, he said he would never photograph anyone “in distress… you must honor all persons”.

Obviously that wasn’t the case, as several of his photographs in Mexico and even the United States included photographs of the homeless.

Takeaway point: I try to shy away from taking photos of homeless people and the destitute. I feel that there has already been so much great and respectable work done on them before– that I am not sure that I could personally do anything better.

But at the same time, photographing the poor and destitute is an important social task. I don’t necessarily agree with HCB in the sense that you shouldn’t ever photograph anyone “in distress.” I don’t think street photography should just be all about happy moments. It should capture the full gamut of emotions from positive to negative.

I think if you photograph those in need in a tasteful and respectable manner – you might be doing society a favor. Instead of just taking a photograph of a homeless person for the sake of them being homeless, why not talk with them and get to know them before even bringing out your camera? Show a genuine interest in their life story and give them some attention. After all, I read that the worst thing about being homeless is not being in poverty, but feeling invisible– that everyone ignores you and doesn’t even give you a second of their time.

Follow your heart to guide you, and know that human beings come first before pictures.

6. On making photography a living

Many people I know dream of making photography a full-time profession. We all have this quixotic dream of living the life of turning our passion into our profession, being able to travel at our own whim and not having to listen to a boss.

But what happens when our passion conflicts with what we are talented with? And what if we try to make our talents into a profession? We can see some conflicts that Henri Cartier-Bresson had turning his career into photojournalism. Westerbeck writes:

“It was the prospect of turning photojournalism into a full-time career. It put him out of sorts, for he remained as conflicted as ever about the medium. Painting was what he preferred, but photography was what he had the talent for.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson started off being interested in painting and studied it rigorously. However he found out that photography was what he had the talent for– and simply referred to his photographs as “instant sketches”. However, he always preferred painting over photography and at the end of his career gave up photography and dedicated the rest of his life to drawing.

HCB also had inner turmoils about taking on photojournalism as a full-time career. It isn’t exactly what he was truly passionate about– but it did pay the bills and give him the flexibility to travel.

Takeaway point: Many full-time photographers I know lose their passion for photography after making it a profession/career. Yet many photographers who have regular “day jobs” wish they could make the jump to pursue photography full-time, perhaps not aware of the full stresses that it may bring.

Know that having a day job can be a great thing in many regards. You will probably earn a steadier/higher income than being a full-time photographer, which gives you the funds to buy the equipment you need, to travel, pay for prints/framing, books, exhibitions, etc.

Not only that, but having a day job can really help you focus on your personal photography 100%. You don’t have to dilute your photography to do assignments or commissions you don’t like.

I am fortunate enough to make a living teaching street photography workshops, but ironically enough even I have a hard time finding time to shoot. In-fact, I probably had more time to shoot when I had my day job, as once I got off my job I didn’t have to work anymore. Nowadays I am far more busy having to travel, blog, answer emails, keep tracks of my finances, which leads to more stress.

I am not trying to discourage anyone from making a full-time career in photography (I love it with all my heart). But if you have a day-job, don’t let that discourage you from creating great art. Know that the grass is always greener on the other side.

7. On Zen and Street Photography

I am an ardent believer in the idea that for any art or craft, it is important to have influences from other ideas or philosophies. Using an outside source helps you get a new and novel perspective on your art, helping you be more creative and thinking outside of the box.

One philosophy that I believe works in tandem with street photography is zen buddhism.

In-fact, out of all the books that inspired Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photography the most was Eugen Herrigel’s “Zen in the art of archery”. HCB explains:

“That book of Herrigel’s, which I discovered many years ago, seems to me to be the basis of our craft of photography. Matisse wrote similarly about drawing—that it was the practicing of a discipline, imposing a rigorousness on oneself and thereby forgetting oneself completely. In photography, the attitude should be the same.. my sense of freedom is like this: a regimen that allows for infinite variations. This is the basis of zen buddhism.”

As Henri Cartier-Bresson mentions, when you are photographing on the street it is important to work hard and not be lazy to the extent that you stretch your creativity to the limits that you totally forget yourself. At the same time, having an open mind and being creative with your shots.

HCB expands on the idea of having an open mind and not “thinking too much” when shooting on the streets:

“Thinking should be done beforehand and afterwards—never while actually taking a photograph. Success depends on the extent of ones general culture, on ones set of values, ones clarity of mind and vivacity.”

Takeaway point: What I got from these two quotes from Henri Cartier-Bresson is that when you are shooting on the streets, to not to try to overanalyze things. When you are on the streets, have an open mind and let opportunities come to you and don’t have a pre-conceived notion of what kind of photographs you want/need to take.

Also when it comes to composition and taking the photograph, enrich yourself in as many photo books and memorable images so you will internalize what makes a great photograph. So when you are shooting on the streets, taking images that are well-composed and interesting, is something that you internalize over rigorous training.

8. On imperfections and ambiguity in photos

As artists, we all have crises in which we feel that our work is uninspired or uninteresting to us any more. In-fact, even Henri Cartier-Bresson has felt this way himself. Below is a story of how HCB was going to destroy his life’s work, as he was dissatisfied with them being “too perfect”:

One day in the mid 1960’s, Romeo Martinez found HCB at Magnum going through his life’s work, intending to destroy the bulk of it. Martinez prevailed upon his friend not to do so; instead Martinez, Cartier-Bresson’s editor and publisher Robert Delpire, and Magnum’s printer Pierre Gasman were each permitted to edit the work. When they had finished, the photographer was still dissatisfied, however, rejecting any pictures they had included that he felt had, as Martinez put it, ”A closed form”. He could no longer accept compositions that relied on formal control. The reason he gave, according to Martinez, was that such images were “Too perfect – they don’t have enough ambiguity.”

Takeaway point: Even the greatest photographers in history have moments of self-doubt. Don’t feel bad if you ever go into these moments– everyone goes through it. You are not alone.

Also remember the other insight that HCB had about his own work he found it to be a “closed form” and “too perfect”. He wanted to have more ambiguity in his photographs.

So for your own work, don’t always strive to make your photographs too perfect. In-fact, I feel it is the small imperfections and odd details which makes a street photo great.

9. On similarities of style/originality in street photography

In the West, one thing that is always stressed is the importance of originality and having a unique style. This causes a lot of frustration in us photographers– because we always have a sources of inspiration that we absorb (either intentionally or subconsciously).

We might even be accused at times of “copying” other street photographers. However I don’t believe that “originality” exists. It is simply a mash-up of all different insights and insights we have received from the past and present. Even Westerbeck shares a similar mentality:

Because photography relies thus on shared insights and perceptions, its vision is as it were, in the public domain. No photographer can really own the copyright on a subject or even a style. Thus is a point of view sometimes possessed jointly by a group of photographers, the way a trade secret might be the members of a guild. In France in the period since World War II, there have certainly been **many other photographers doing work comparable to, and in cases indistinguishable from, that by Doisneau to this fraternity of Parisian photographers belong—besides Kertesz and Cartier-bresson or Brassai – Willy Ronis, Edward Boubat, Guy le Querec, Marc Riboud, Inge Morath, Richard Kalvar, Rene Maltet, Izis, Leonard Freed, Gilles Peres, and many, many more.

In France since World War II, the heavyweights of photography were Robert Doisneau, Andre Kertesz, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Brassai. Of course all of the younger photographers of their generation would gain much inspiration from them in terms of both subject-matter and aesthetic style.

Famous American photographer Walker Evans also shares how he was also quite inspired by other photographers, like Eugene Atget for his large-format work of Paris:

In spite of the obvious debt he owed to Atget, Evans afterward claimed that he was unaware of the aged Parisian’s work “Until I had been going for quite a while,” as he told some undergraduates at Harvard two days before he died. The motive for such denial becomes clear later in his remarks when he admitted that, once he had discovered Atget’s work, “I was quite electrified and alarmed.” He explained,‘Every artist who feels he has a style is a little wary automatically of strong work in view. I suppose we are all a little insecure. I don’t like to look at too much of Atget’s work because I am too close to that in style myself. It’s a little residue of insecurity and fear of such magnificent strength and style there. If it happens to border on yours, it makes you wonder how original you are.’

Even Evans who created the first seminal work on America admitted his insecurity in terms of what he had to owe to his inspiration to Eugene Atget.

Takeaway point: Don’t feel this pressing need to be truly “original” in your street photography. Devour as many inspirations you can both in photography books and on the web. The more photography that I personally look at, I start to get a better understanding of what kind of photography appeals to me and what doesn’t.

Know that even photographers from many decades ago weren’t truly “original” in their photography and I feel that the same concept applies today.

But once again, pay homage to the master street photographers and never stop learning from the work of others. Sources to spend your time to be inspired by great work: The Magnum Photos website, Invisible Photographer Asia, the Hardcore Street Photography Group, as well as street photography books.

10. On working on long-term projects

One of my favorite books of all-time is Gypsies, by Magnum photographer Josef Koudelka. He spent close to a decade– living, traveling, and photographing the Roma people from all over Eastern Europe. His images are incredibly intimate, and visually powerful. How was he able to create such a masterpiece? Well, Koudelka attributes it to the fact that he was able to work undisturbed for a long period of time:

Koudelka is in a privileged position at Magnum because he is allowed to remain a member without having to take the regular assignments through which the others contribute to the support of the cooperative. “Publishing photographs is not important to me,” he says; “I like to concentrate on working and not to be disturbed.” The project that gained him the status to be able to work in this way was also the one that led him to become a man without a country – a study of the Gypsies that he did in Czechoslovakia between 1962 and 1968.

Takeaway point: Great projects take a lot of time. Don’t feel that you need to rush it. Expect that a long-term project is going to take longer than you expect it to be. Many of the great long-term projects I know and love (another great example of Jason Eskanazi’s “Wonderland”) take up to 10 years, or even a lifetime.

11. Sociology and street photography

There are many different types of approaches in street photography. You might be interested in documenting interesting moments, history, visual images, or even photos that have a sociological edge.

Lewis Hine was the archetype of a sociological street photographer. Not only were his photographs visually interesting and well-composed, he strove for deeper meaning in his photos. He wanted create images that informed others of certain social working conditions, and wanted his photographs to make a change in society. Westerbeck writes:

Hine was in essence a researcher who published his findings in sociological journals. His ideas had more complexity—or at leas a duality—which made taking photographs a greater challenge. As he put it in his characteristically terse, unornamented fashion, “I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated.”

Hine spent much of his time photographing unfair working conditions in places such as mines, factories, and mills. Westerbeck writes how he approached his subjects and documented them:

When Hine worked on the street, he had two or three different approaches. The simplest was to do loosely posed group portraits like the one of immigrant Russian steelworkers made in 1907 for a Kellogg study entitled The Pittsburg Survey. Since the relatively new Graflex camera Hine used was a top-viewer, it was held at waist level. The closer Hine moved, the more the camera had to look up to its subject. This gave the figures in the street portraits a rather heroic prospect.

The Russian immigrants were photographed in the Pittsburgh suburb of homestead, where steelworkers like them had been shot in the streets during the homestead strike of 1892. The breaking of the strike with scabs, troops, and Pinkerton agents had crushed the first effort to organize steelworkers into a union. But now, massed in the frame and photographed from below, the men in Hine’s picture seem to present a new image of solidarity. They have the dignity and presence, the human spirit, that Hine wanted us to admire.

But what exactly made Hine a “street photographer” per-se? Westerbeck explains:

What gives Hine’s street photography its character is the ability he had to adapt that portrait aesthetic to the street. Even when he photographed candidly, stepping back to get the full figure in the frame and trying to catch the action of a scene, he still made the pictures serve the pledge that he had taken as a photographer: “Ever- the human document to keep the present and the future in touch with the past.”

Takeaway point: When you are shooting on the streets, not only is it important to make visually interesting photographs but photographs that may have a deeper meaning. If you are inclined, try to make street photographs that are more sociological in nature. Try to approach certain communities or areas which you think there is some sort of injustice and use your camera as a sociological tool to report and spread awareness.

I studied Sociology as an undergraduate, and one of the things that I definitely want my photos to do is to say something deeper about society. This is why I am working on my “Suits” project in which I want to shed light on the fact that money doesn’t always buy happiness– and the restrictive nature that working corporate can often have on the human soul.

12. Painting and photography

There are many street photographers who first had an interest in art from painting. This includes Henri Cartier-Bresson and even Walker Evans. This is what Evans shares about why he started photography:

When asked why he took up photography, Evans once said, “I think it came from painters. Several of my friends were painters. And I had a visual education that I had just given myself.” The education was obtained in Paris, where, unable to write as he had planned, he spent a good deal of time looking at the new painting. “The school of Paris was so incandescent then,” he recalled, “A revolutionary eye-education”. It was not only the example of Picasso and Braque that showed Evans the way but, as he himself admitted, his friends back in America, such as Stefan Hirsch, who were also painters.

However how much inspiration should you take from other painters and artists? Evans shares:

“When you are young you are open to influences, and you go to them, you go to the museums. Then the street becomes your museum; the museum itself is bad for you. You don’t want your work to spring from art; you want it to commence from life, and that’s in the street now.”

Takeaway point: One of the best ways to improve your eye for design and composition is to look at paintings. Due to the fact that painters can control their subject-matter and framing, they often have better composition than photographers. Go to museums, devour art books, and study art history. Having a strong background and knowledge in painting and art will help your street photography composition tremendously.

However Evans also warns photographers not to spend too much time in the museum- but on the streets, which is the ultimate inspiration.

13. Shooting on the streets with other people

Street photography is often a solitary pursuit. However it can be advantageous to shoot in the streets with other people, especially a partner you gel with in terms of approach and passion. In-fact, two of the biggest legends in street photography Joel Meyerowitz and Garry Winogrand often shot together. From an interview from Bystander, Colin Westerbeck interviews Joel Meyerowitz on his experiences:

Colin Westerbeck: Then there were several years when the two of you went out shooting together, didn’t you? How did that come about?

Joel Meyerowitz: Garry loved company. He needed to be out on the street, and he needed company out there with him all the time. It was irresistible. He was irresistible. He was so full of, “Let’s go! Let’s do!” Right from the beginning, he would call in the morning and say, “Listen, I’ll meet you at the greasy spoon on Ninety-sixth and Amsterdam: we’ll have coffee, well go off, well shoot.” I was up and ready to go, I was off and running for three intense years- 1962 to 1965. With this guy, the unstoppable bundle of nerves.

14. The importance of constructive feedback & critique

Social media is a blessing and a curse. For one, it has allowed us to connect with so many other street photographers from around the globe. However on the other hand, most of the feedback/critique we give one another is limited to feedback such as: “nice shot!”, “great!”, or the “like” button.

I know this is a problem because I am guilty of it it too.

The problem of social media is that there is often too much information we get. We see too many photographs from too many other street photographers. We want to give everyone feedback, but the more people we give feedback to, the overall quality of the feedback/critique falls short.

How did street photographers used to give one another feedback back in the day? Well first of all, they did it mostly in person. This is how Joel Meyerowitz explains how he and Tony Ray Jones used to critique one anothers’ images:

“Every night we would pick at each others exposures. Splitting hairs, trying to make exquisite exposure judgements instantaneously. You know— “what did you shoot that at? Why didn’t you go slower and have more depth of field, or get closer, so you would have that in focus and that out of focus?” We were analyzing and grinding away at our pictures, and liberating ourselves.

In any art or craft, to get honest and constructive feedback & critique is crucial. Sure it is nice to get a pat on the back for our photos after we upload them, but it won’t help us get better.

I often feel guilty not giving all of my friends and colleagues feedback/critique in their street photography. However there are only so many hours in a day so you have to be selective when giving feedback/critique.

Takeaway point: My suggestion is to limit the amount of feedback/critique you give on Facebook, Flickr, Google+, Instagram, 500px, whatever social media platform you use. Aim for quality over quantity.

Just follow a few photographers and give them feedback/critique that is both thorough, honest, and useful. Tell them what you like about their photograph and what you think could use improving.

I get lots of one-liner responses on my photographs. As much as I appreciate them, if someone sits down and writes out at least 4 sentences or more as feedback it means so much more to me. I then add that person as a contact, send them my regards, and build a connection with them. If you build that connection with others.

So instead of waiting on others to start giving you quality feedback and critique like Ghandi said, “be the change in which you wish to see in the world.” Start giving other people helpful feedback, and they will most likely reciprocate or at least notice and appreciate it.

15. On the fear of shooting street photography

Jacques Henri-Lartigue was a French photographer, who shot a lot of photographs in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. He grew up in a wealthy family, and started photographing at a very young age. He documented much of his privileged life men racing in cars, people flying in planes, and one of his favorites, fancy women.

Interesting enough, Jacques Henri-Lartigue was not “discovered” for his photography until he was in his 70’s, by MOMA photography curator John Szarkowski. Not only that, but Henri Cartier-Bresson had once told Newsweek Magazine that out of all photographers, he admired Lartigue the most.

But to get back to Henri-Lartigue, he kept a daily diary of his photographic experiences. This is an interesting except of how he felt photographing this beautiful women (without permission) and his sense of nervousness:

She: the well-dressed, eccentric, elegant, ridiculous or beautiful woman I’m waiting for… there she comes! I am timid… I tremble a little. Twenty meters… ten meters.. five meters… click! My camera makes such a noise that the lady jumps, almost as much as I do. That doesn’t matter, except when she is in the company of a big man who is furious and starts to scold me as if I were a naughty child. That really makes me very angry, but I try to smile. The pleasure of having taken another photograph makes up for everything! The gentleman ill forget. The picture I will keep.

I know that many of us as street photographers are often nervous and timid photographing strangers on the streets. However know that this is not a phenomenon just to us– but to our forefathers who shot in the streets more than a century ago.

Takeaway point: Almost every street photographer I know has some certain level of fear when photographing strangers in the streets. Know that over time you will mostly overcome it, and build your confidence with the right attitude– and with practice.

However don’t let the fear of shooting street photography deter you from documenting the world around you. We might be afraid of people yelling at us and becoming confrontational. Even Jaques-Lartigue was scolded for photographing that elegant women by a large man who was perhaps her boyfriend or husband.

16. On making “non-judgmental” street photographs

I don’t think that there is any human being that is purely objective when it comes to seeing the world. We all see the world through our own perspective– our own lens (pun intended).

While I do think it is important to create subjective images which make our images unique it is also important to sometimes be a little more neutral and less “judgmental” when it comes to our street photographs.

One prime example of “amoral” nonjudgmental street photographs is that of Henri Cartier-Bresson. What made his photographs so amoral? Westerbeck explains:

The image doesn’t seem to have a specific story to tell, or if it does, the story has no particular point to make, no obvious moral. The photograph is, as Levy said, “amoral.” Like the print, the content of the picture is strangely neutral in tone. Lincoln Kirstein has pointed out that Cartier-Bresson “is not even an ironis, for irony… presupposes a partial judgement.” This photographer’s observations on human nature are neither misanthropic nor philanthropic. His ability to walk down a street in Paris or Seville or Shanghai, and respond with such equanimity to whatever he finds there, results from his openness to human experience in all its forms.

Although several of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs are quite fun and joyous (think of the little kid running in the streets with the two bottles of wine with a proud look in his face) I too notice that most of his photographs are quite neutral in tone.

I think this is because Henri Cartier-Bresson was trained first as a painter and was primarily interested in composition and form when it came to his photographs.

Takeaway point: The favorite part of the excerpt that I quoted above is that Henri Cartier-Bresson responded with “equanimity” regardless of where he photographed and had an “…openness to human experience in all its forms.” So pretty much to sum up, he wasn’t discriminatory of his subjects.

I feel we should treat our subjects in street photography with the same sort of respect. Sure we may see the world in a more positive or negative light, but whenever you travel to different places or areas give people the same amount of respect and compassion. Be open to the lives of others and of the “human experience”.

If you shoot street photography mostly in New York City and photograph people a certain way, don’t suddenly treat your subjects from Asia in a different way. And vice-versa.

17. On the importance of small details

Another insight we can gain from Henri Cartier-Bresson is the importance of the small details in a photograph. This is what he shared in an interviewer from Le Monde in the 1970’s:

“What counts are the little differences “general ideas” mean nothing. Long live… the details! A millimeter makes all the difference.”

Takeaway point:: Know that when you are shooting on the streets, that the small details in the background are what make the photograph great. I like to call these small elements in the photograph “the cherry on top”. Think of HCB’s famous photograph of the man jumping over the puddle. Sure it is an incredible image, but did you ever notice the small detail of the ballerina poster in the background also jumping the opposite way? That is the cherry on top.

Also when you are shooting on the streets, realize that “a millimeter makes all the difference.” This means to sometimes create a surrealistic effect in your image, move your feet! Don’t be a lazy street photographer and just take one photograph from a scene and move on. Crouch, take your photograph a little from the left, a little from the right– get closer, or even take a step away.

b) Technical Insights in the History of Street Photography

1. Early 1900’s arguments on bokeh vs sharpness

I don’t think that there is a certain way you have to shoot street photography. Generally I prefer photos taken at f/8 and I don’t like photos that are shot wide-open (so I can see more context in the scene).

There are a lot of arguments on the web about sharpness vs bokeh, having shots in-focus vs out-of-focus, black & white vs color/hdr/etc. Although this seems like contemporary issues, know that photographers in the past have also argued relentlessly about this.

For example, here is an excerpt from Bystander which photographers from the late 1800’s-early 1900’s argued over “soft focus photos” versus sharp photos:

Emerson had contempt for photographers who made gum prints—“paper strainers,” he called them – and Stieglitz, in turn, came to disapprove of the soft-focus technique Emerson advocated. The first advice Stieglitz gave Strand was to stop down his lens to eliminate its emersonian softness, which was, he told his young protégé, “destroying the individual qualities of … life” in his photographs.

In another instance, for Alfred Stieglitz’ famous “Winter- fifth avenue, 1893” photo, people hated it because it wasn’t “sharp”. But it was the blur that made the photograph:

When Stieglitz showed the negative at the New York Society of Amateur Photographers, the response was, “For gods sake, Stieglitz, throw that damned thing away. It is all blurred and not sharp.” His comeback was that it had turned out “exactly as I wanted it to be.” He told his incredulous listeners, “This is the beginning of a new era. Call it a new vision if you wish”.

Takeaway point: I am personally not a fan of HDR/selective color/other over-the-top types of photo-processing. But I try to remind myself that it is only my opinion– others can do as they please. After all, photographers have been debating different ways of manipulating negatives, cropping, and printing their photos for decades.

So feel free to experiment with the way you photograph and post-process your images. Don’t care about what other people say, do what makes you happy. But I still am a fan of consistency so if you do experimental work, try to keep it all in one set or project.

2. How important is sharpness in street photography?

One disease that many photographers nowadays have is an obsession over sharpness. We can see this in countless numbers of photo forums where people test different lenses and apertures against brick walls.

Henri Cartier-Bresson once said that “sharpness is a bourgeois concept” which rings loud and clearly even today.

Interestingly enough, he once told Beaumont Newhall at his first exhibition at Museum of Modern Art that he liked “aigu” (the French word for sharp) images. What did he mean by that?

Westerbeck explains how he interprets this statement:

Aigu refers “not so much to the quality of the optical image as to the precision of the plastic organization and the intensity of the content.”

This is an important point to note, because many of HCB’s most famous images were quite soft, especially if you have seen any of them blown-up large as prints at exhibitions or galleries. Think of his famous photograph of the man with the sinister eye in the bull pit in Spain. If you look at the photograph, it is considerably out-of-focus, yet it remains to be a memorable and incredible shot.

Takeaway point: Don’t worry about sharpness in street photography. That is one of the beauties of street photography that the technical points are often not very important. What is more important is the content in the frame, and how you compose it and the effect that it gives the viewer.

So unsubscribe and un-bookmark all of those gear forums and websites. They are just giving you serious G.A.S. and distracting you from actually going out and shooting with the great camera and lens you already have.

3. On shooting street photography in color

Today we are blessed with technology that allows us to shoot in RAW. We have the luxury of shooting and deciding afterwards whether we want to keep our images in color or black and white.

However the problem I have noticed by working in this manner is that it lacks consistency. Not only that, but based on my personal experiences– I tend to see the world differently when I make the decision to shoot in black and white and also shoot in color.

So how do photographers see the world differently when shooting on the streets in color (from the traditional black & white?) One of the first early proponents of color street photography, Joel Meyerowitz, shares his experiences with Westerbeck:

“Color forced me to behave differently. Its powers of description were greater, but it was also slower. If my subject and I were both in motion, the picture wasn’t always sharp, so I tended to photograph from farther away than before.”

When Meyerowitz was shooting color at that time, the speed of the film was incredibly slow, at around 25 ISO. Therefore in order to get his photos sharp, he would have to shoot from further away and not be moving himself. Compare this to when he shot black & white Tri-X film at ISO 1200 where he could shoot quickly and constantly in-motion.

Meyerowitz also explains how the “power of description” of color was greater. If you look at his color photographs and his black & white photographs, the content also tends to be different. With his black and white work, he often worked closer and had fewer subjects in his frame. But with color, he took a step back and would add far more elements and complexity to his shots as color would allow for that separation.

Takeaway point: When shooting street photography, I encourage you to make the decision to shoot in color or black and white before you hit the streets.

Why? Based on my experiences– when I shoot in color I tend to look for colors, complexity, and other visual elements of everyday life. In black & white, I tend to look for more abstract images that consist of shadows, geometry, and forms.

I also suppose you will have a similar experience. I still encourage you to shoot in RAW (if you are shooting in digital) so you can have more flexibility in the post-processing afterwards and have more information in your files.

Another tip I have is you can set your preview screen (while shooting in RAW) to default (color) or black & white– to give you a sense of what your final images will look like. As always, don’t chimp while shooting in the streets but if you sit in a cafe and want to quickly review some of your shots, this will give you a better visualization of your final images.

4. On shooting with high-ISO

I often meet street photographers who refuse to shoot on the streets with an ISO higher than 200 because fear of grain. What may be a problem with this? Well if you are shooting with a high f-stop to get a deep depth-of-field (like f/8) your shutter speed will often be too slow.

How did the masters shoot their film?

Well in the early days of photography (late 1800’s to early 1900’s), street photographers were constrained by relatively slow films like ISO 25 film. But as technology advanced (and ISO 400 film became available) some legendary street photographers like Joel Meyerowitz and Garry Winogrand were pushing their ISO 400 film to 1200 ISO. This allowed them to shoot at the maximum shutter speed of the Leica’s they were using (1/1000th of a second). Joel Meyerowitz expands on this idea to Colin Westerbeck in an interview:

We were using Tri-x film pushed to 1200 ASA (ISO), whereas its normal rating is 400. The reason was to be able to shoot at 1/1000th of a second as much as possible, because if you made pictures on the street at 1/125th, they were blurry. If you lunged at something, either it would move or else your own motion would mess up the picture. I began to work that way after looking at my pictures and noticing that while they had these loose edges, Garry’s were crisp. Frank didn’t work that way, his pictures were much slower. You could see that he was working at 1/30th and 1/125th.

Pushing Tri-X to a higher ISO adds grain and contrast. Not a lot of photographers like that.

However now we are now blessed with technology and cameras that have ridiculously good high-ISO performance. We can shoot at ISO 1600 without seeing any noise. I even have shot with some new cameras that can shoot at ISO 25,000 with minimal noise. It is a brave new world.

If you are shooting street photography and want minimal blur and sharp photos, shoot with a high-ISO. Don’t be afraid to push your camera to 1600 or even 3200. Even if you are shooting street photography during the day.

Based on my experience you need a shutter speed of at least 1/250th of a second to photograph someone walking at a moderate pace (without them blurry). If someone is running, you want at least 1/1000th of a second.

Let me give you an example (for those with digital cameras that have fast shutter speeds): If you are zone-focusing at f/8 during the day in the sunlight (at ISO 1600) your shutter speed will adjust itself to probably be in the range of well over a 1/1000th of a second. However once you shoot in the shade, your shutter speed will drop to 1/250th a second (the minimum shutter speed to capture motion)– even with ISO 1600.

Takeaway point: Don’t be afraid to shoot with ISO 1600 or even faster when you are shooting on the streets. It will better help you capture “the decisive moment”.

5. On shooting in different lighting conditions

Every street photographer has different preferences when it comes to lighting. Some of us like shooting during the day, others at sunset/sunrise, and others of us at night.

When did some of the greats of street photography enjoy shooting?

Apparently Henri Cartier-Bresson preferred to shoot when it was cloudy. Why? Westerbeck expands below:

First, literally, the pictures are without contrasts of bright light and deep shadow with which much art photography of the day created bold graphic patterns in the prints. If there is sunlight in a Cartier-Bresson photograph, it usually falls on the background, while the foreground subjects are in shade. Preferably, there is no sun. Cartier-Bresson would rather photograph on a gray day.

What did Cartier-Bresson say about the sun himself?

“The sun is very troublesome: it forces, it imposes. Slightly overcast conditions allow you to move freely around your subject.” Moreover, he has always liked the print itself to be gray and even in tone. He has wanted it to be, as John Szarkowski once put it, “a tapestry.”

Takeaway point: Shooting street photography on cloudy days does give you flexibility. Although the light tends to be flat, it tends to be quite even. This allows you as HCB mentioned, “…to move freely around your subject.” Furthermore, HCB preferred his photographs to be more “gray and even in tone.” So don’t be discouraged when shooting street photography when the light may not be so epic outside.

Furthermore, I think that the common aesthetic when it comes to black and white street photography is high-contrast. Know that most of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs are quite low in contrast. So don’t feel obliged to slide your contrast filter to the maximum. Sometimes having a photograph more even in gray tones makes for a more serene image.

c) The Use of Different Cameras/Equipment for Street Photography

1. On experimentation with different approaches

One important way to maintain your creativity as a street photographer is to be constantly experimenting. Even Andre Kertesz in the 1920’s was experimenting not only with his approach but also with his equipment:

Some experiments Kertesz began to make with different lenses were also a sign of his increasing concern with formal issues around the time. In 1927, for a view looking down a public stair in Montmartre, he removed the front element from the lens assembly on his Voightlander camera. The result was a slight telephoto effect that flattened the scene and thereby made the picture function more as a two dimensional surface. This pleased him, so he developed various ways to enhance it, eventually acquiring custom-made lenses ranging from 90mm to 260mm.

The lenses that Kertesz used to use were quite wide, and over time– he wanted to create a new type of image. He wanted to have a photograph that was flatter in perspective and more two-dimensional.

He figured out that by tinkering with the assembly on his camera, he was able to create the type of “look” and vision he wanted. Not only that, but he eventually started experimenting with other lenses and seeing how it would change the perspective in his images.

Takeaway point: I don’t think we should take this story from Kertesz and use it to simply justify us going out and buying a whole bunch of new cameras and lenses to justify our vision.

I would say that Kertesz had a certain concept or idea in mind (in this case creating more flatness in his images) and the only way he could do that is by using different lenses (telephoto lenses). Of course he discovered this concept by accident, by tinkering with the front assembly of his lens.

I encourage everyone to experiment with different types of approaches in street photography (candid, posed), with different lighting (natural, flat, flash), with different cameras (digital, 35mm, medium-format, large-format), and different types of processing (b/w, color, toning). It is important to always be experimenting for different projects or ideas you might have in mind.

But once you feel that you have found an approach that suits you, I would say stick with it. There is a fine line between buying new cameras/lenses/equipment to help us achieve our artistic vision and just having G.A.S. (Gear Acquisition Syndrome). It is a hard line to balance (there are many times I fall into G.A.S. as well) but try to remember no camera or lens in itself will make you more creative. It will only be your passion and ingenuity which will do so (and the equipment will help you achieve that).

2. On working with a large-format camera

There are many different types of cameras out there especially when it comes to analogue. You have 35mm SLR’s, 35mm rangefinders, medium-format TLR’s, medium-format rangefinders, all the way up to large-format cameras (and many others I’m not mentioning).

One thing I have discovered about using different cameras is that you have different approaches. So how is it shooting on the streets with a large-format camera which is huge, heavy, and cumbersome to use?

Berenice Abbot was one of the famous street photographers who documented NYC with a large-format camera. Westerbeck writes:

Another supposed disadvantage of the view camera—its inversion of the image on the ground-glass back—also encouraged Abbott to experiment in a distinctively modern way**. As she explained in her essay about view cameras, “With the image inverted we can compose ‘abstractly’, in a sense that the distribution of lines of light and shade in the composition are seen fully… we can, for the time being, forget the subject and think of its design.”

Takeaway point: Abbot shared that shooting on a large-format camera helped her see his subjects and composition in a more abstract way. For those of you who don’t have much knowledge about large-format cameras, when you look at the glass plate in the back of the camera to compose– the image is inverted. Therefore you see your subject upside-down, which Abbot wrote was a benefit.

Experiment with different cameras that have different viewfinders. A SLR might suit you in the sense “what you see is what you get”. Or you might want a wider-field of view, then a rangefinder will help you see outside the frame lines. Perhaps you want to shoot in a square-format, try using a TLR camera and shoot from the waist-level. Or if you are daring enough, even try a large-format camera.

3. On using wide-angle lenses

Many different types of lenses are utilized in street photography. Most commonly used are the 28mm, the 35mm, and the 50mm.

With different focal lengths– you create a different type of image. The wider you go, your images tend to feel much more intimate– as the perspective makes you feel that you are really in the photograph as an active participant, rather than an outside voyeur.

One of the great thing about Koudelka’s “Gypsies” project is that he photographed with a very wide lens (a 25mm) which drew you close to his subjects:

This psychological involvement had an optical counterpart in the wide-angle lens he used for much of the work, a 25mm that permitted him to stand in the midst of the people he was photographing. With Gypsy subjects, who tended toward expansive moods and impetuous gestures, this lens produced pictures in which arms, legs, and even whole bodies fly in every direction. Kids sliding on the ice in the yard in winter veer toward the edge of the frame, threatening to puncture it with their sprawling limbs. A dog that refuses to sit still for a family portrait bolts from the picture plane as if about to leap right out of the photograph. There is a visual anarchy in the pictures to match the wildness and lawlessness of the Gypsies themselves.”

William Klein was another photographer who was quite the anarchist. He despised the conventions of photography, one of them being shooting with a “normal” 50mm lens. He far preferred the chaos of wide-angle lenses:

Among the laws Klein broke were Cartier-Bresson’s. “I liked Cartier-Bresson’s pictures,” he says, “But I didn’t like his set of rules. So I reversed them.” Since Cartier-Bresson had declared the 50mm lens to be the norm for street photography, Klein preferred one with a wide angle. More important, instead of being inconspicuous and unobtrusive with his camera, he used it as a provocation. He stuck it in his subjects’ faces. He brandished it at them as if it were a Saturday night special he was using to stick up a liquor store. The rules he could violate by doing so included not only Cartier-Bresson’s but those which he himself had to live as a boy. Now there was nobody he was afraid to look into the eye.”

Takeaway point: Everyone has their own preference when it comes to focal length. I would say experiment with different focal lengths, and find what suits you the best.

In Koudelka’s “Gypsies” he was able to create very intimate photographs using a 25mm. Which meant that he was literally up-and-close and part of the action. The fact that he had to get close to the Roma people (physically and emotionally) is what I think made for the great project. Klein also used a wide-angle lens (from a 21mm to a 28mm lens) that better suited his in-your-face personality and his intense images.

I have experimented with a lot of different focal lengths, and I have found that 35mm suits me quite well. The 28mm could be a little too wide for me at times, while the 50mm felt a little too restrictive at times. 35mm seemed to be a nice trade-off between both.But of course, that is only my opinion.

Experiment with different focal lengths, but once you find a focal length that suits you well– I would stay stick with it. It will help you to understand a focal length very well, and know how far or close you have to stand to your subjects to create a certain frame. Not only that, but it will create a visual coherence in your images that are consistent across a project you may pursue.

4. On the use of flash in street photography

One of the hotly debated things on the internet is the use of natural light vs flash in street photography. Although famous photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson were strictly opposed to using a flash when shooting on the streets many photographers before him were using a flash to assist their work even before him.

For example, one of the first photographers to use flash in the streets was a journalist and reformer named Jacob Riis. He first started shooting in the streets with flash powder in 1887, to create images that would help support his lectures and publications for destitute people on the streets. Westerbeck shares Riis’ approach:

“[Riis’] involvement with photography began in 1887, when he first read about the invention of flash powder, or Blitzlichtpulver, as it was called. He realized at once that it would permit him to record directly the conditions in the airless halls and windowless rooms of tenements. To obtain the flash shots, he often sneaked into a tenement or a dive, set up his equipment under cover of the semi dark, fired off one exposure, and beat a hasty retreat before the blinded subjects could recover their senses.