All photos copyrighted by Zoe Strauss / Magnum Photos.

About a year I stumbled upon the work of Zoe Strauss in her book: “America.” I was amazed with the power of her portraits as well as how she masterfully combined them with signs and urban landscapes. Also in terms of the book, they are some of the most powerful diptychs I have ever seen.

I recently checked out a copy of her newest book: “Zoe Strauss: 10 Years” and wanted to write an article about her work. She has an incredible story, and equally incredible images to back it up.

Warning: Some of the photos in this article are graphically intense which are Not Safe For Work. This includes nudity, physical violence, which should not be seen by minors or people who are uncomfortable with these types of images.

1. Great projects take a long time

One of the biggest things that thrust Zoe Strauss into the public eye was her I-95 Project. Pretty much the concept was that she publicly exhibited her photos under the concrete support pillars on the I-95 in Philadelphia. Strauss explains more in-depth about her I-95 project:

“I-95 was an epic narrative about the beauty and struggle of everyday life, comprising 231 photographs adhered to the concrete support pillars under an elevated highway that runs through South Philadelphia, Interstate 95. The installation of photos went up once a year, from 1pm to 4pm, on the first Sunday of the month. I worked on 95 for a decade, from 2000 to 2010.”

Strauss shares how she worked on the concept of the I-95 project:

“The concept for 95 came to me pretty fully formed, and I spent a little more than a year making sure the concept was strong and the execution was going to be rock solid. With money I got from my wife and immediate family for my 30th birthday, I bought a camera within the month and began to make photos for the installation.”

Surprisingly, Strauss came up with the concept first– and then picked up photography to pursue it. She also truly dedicated her life to making sure the public exhibition would be executed:

“I had, and still have, very little interest in exploring how this idea came to me. I don’t care about why. But I did care a great deal about bringing it to fruition and completely committed to doing so. In nailing I-95 down, I endlessly mulled over the format and laid out a blueprint for the installation. For example, I knew from the start it had to be a 10 year project.”

Zoe Strauss took 10 years to work on this one project. Why did she decide 10 years? She explains:

“A decade would allow me enough time to make a strong body of work. I needed to learn to make photographs and couldn’t gauge my capability until I actually started working. Setting a time constraint assured that the installation wouldn’t be overworked. Plus, I could go at it as hard as possible without fear of burning out.”

Takeaway point:

I think in today’s world in photography– we try to rush our projects and our concepts. Not only that, but with the rise of social media– we are just uploading single photos without some greater concept or plan.

10 years is a long time to work on a project. But Strauss knew that she would need all of that time to learn the technical skills she needed, and also the time to create the types of images she needed.

I think what we can learn from Strauss is that great projects take a long time. Don’t expect to finish an ambitious project in just a year or two. It might take up to 10. Don’t rush it– take your time, and make it great.

2. On taking portraits

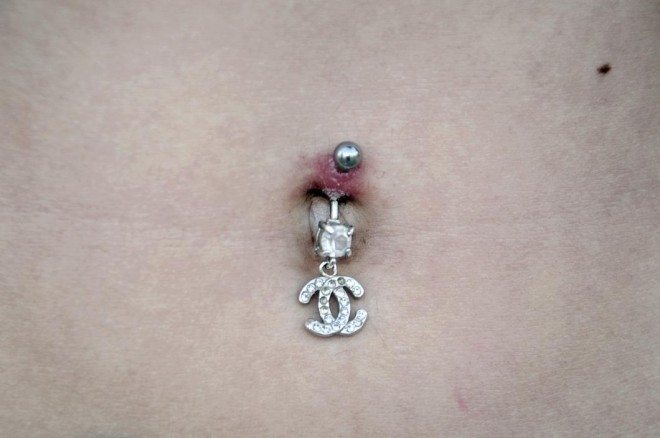

One of the most striking things about Strauss’ work is how powerful her portraits are. Not only that, but she captures her subjects in a sensitive way– while they expose themselves to her. She has taken photos of people nude, people battered and bruised, and doing drugs. How does she get her subjects to feel comfortable around her taking their photo?

Strauss starts off by explaining how choosing her subjects is an unconscious decision:

“In terms of making a portrait, the camera is the introduction. I approach someone with the intent of making a photograph and what attracts me to the person is intangible.”

Strauss expands on sharing the importance of building a connection with your subjects:

“Later on in the edits it seems as if the portraits that have the greatest importance to me, and have the greatest satisfaction, are the ones where I have had some sort of connection with the person, and that almost always involves a connection that can not be articulated

a sense of pride and joy of being in the world. It doesn’t matter what the situation is but there is a connection, without sounding ridiculous or hokey, we are both happy to be alive, and that’s the biggest part of it.”

Strauss also shoots most of her work digitally– and one of the ways she builds a sense of trust and rapport with her subjects is by showing them the LCD screen:

“If I’m taking digital photos, if it’s a portrait, I always show them.”

Strauss also deletes the photos if her subjects don’t like them:

“Even if it’s difficult, I know they’ve seen it. Using someone’s personal image as a metaphor for other things, I try to pay attention that these are real people. I’m not interested in a representation of someone in which they are grotesque, and they don’t know they’re being presented like that.”

Strauss has also dealt with a lot of rejection when trying to take portraits of people on the street:

“I’ve stopped hundreds of people and asked to make their photo. If it’s an up-close portrait, I always ask the person if I can take the photo. Often the answer is “no”.”

However regardless if she takes a photo or not, she values the interactions greatly. She elaborates how sometimes great interactions can lead to boring photos, and short interactions can lead to intimate images:

“But if a photo doesn’t come out of the meeting, it doesn’t make the interaction less important or interesting. Sometimes a great interaction will result in a boring and unengaging photo and sometimes a two-sentence exchange and good-bye will result in a deeply intimate portrait. I can never be 100 percent sure, and sometimes I’ll need a little distance from the exchange in order to know if a portrait is successful.”

When asked about her photographic heroes, Strauss shared it was the WPA photographer– because of the dignity they kept for their subjects:

“I love a lot of photography but I really feel connected to the WPA photographers. I feel like that was—you know Dorothea Lange—an interesting important moment. I’m fascinated by that idea, the interaction between the photographer and subject is the photographer’s choice in this instance. So many iconic images that come from that period we see without thinking of the choices of the photographer. So in terms of preserving the dignity of the subjects and meeting the needs of the assignment the project was successful in many instances.”

Takeaway point:

The backbone of Zoe Strauss’ work is her ability to become intimate with strangers, and take riveting portraits. Although she has been criticized by photographing the poor and destitute as well as marginalized people in society– she gives them a voice. She interacts with them. She makes them a part of the picture-taking process. And if her subjects don’t like the photos, she decides to erase them.

It takes a huge amount of courage to step outside of your comfort zone and ask a stranger to take their portrait. Why is that? Well, you have the possibility of rejection. Nobody likes to be rejected– it is a discouraging feeling and emotion.

However at the end of the day– don’t just concern yourself with taking photos. Try to focus on the interactions you have on the streets as well. To me personally the interactions on the streets I have with strangers are as valuable as the photos themselves. And sometimes the interactions are more important to me than the photos. It makes me feel more like a human being– connecting with others in society, and also treating them as human beings (not just photographic subjects).

3. On putting together a book

In an interview, Zoe Strauss shares her experiencing editing, sequencing, and pairing her images in her book: “America.” She shares the insanely difficult process in-depth below:

“It is torture. It was so phenomenally painful. It shouldn’t be but it just really really was. I had no idea how hard it was to put a book together. I certainly didn’t think it would be easy, but a big part of my work is editing and I thought that I would get through it. I was so fucking wrong. It was grueling and extraordinarily difficult. I would go back and forth about the narrative and the balance of the book, the mood, what the juxtapositions say on the page, is the text conversational and not descriptive of the photo but rather of the process, I was losing my fucking mind. And not to say that I didn’t love it, I really did, and I couldn’t be any more happy that someone gave me the opportunity to make a book, but I was really like, ‘Oh my god.’”

One of the things I loved about most in Strauss’ “America” is the pairing of the images– or the diptychs in the book. She shares why she decided to pair certain images together in a diptych format:

“I really love it. It’s a good format for my work and allows these two photos to have this exchange. In some ways that’s how the I-95 project works, as these photos have this movement. It was really so much more difficult than I would have thought and I don’t know if I am going to continue to work in that.”

Strauss shares how combining two images can create a new meaning:

“The placement was as important as each individual photo. There is a photo of a guy with swastikas, and I really love that guy and I want that to go next to the photo of the sign that said “Paris in jail” because I felt that was a WWII reference and a historical strain, but I felt like I couldn’t have those two next to each other on the basis that it was implied this guy had gotten the tattoos in jail and it changed the meaning of what it means to be in prison.”

Strauss shares how diptychs can create a different emotion and mood:

“The placement of that one was very difficult for me because I knew those two had to be close to each other and I didn’t know how they were going to relate to each other and it was really obvious that the mood would change dramatically if it was on the opposite page or next to it. And it turns out that most of them were like that.”

Takeaway point:

One of the most beautiful things you can do with a book is play with the pairing of images. This creates so many opportunities of combining your images to invent new meanings.

Whenever I look at a photography book, I always ask myself questions such as:

- Why did the photographer choose to pair these two images together? What meaning do they create?

- Why did the photographer choose to sequence the book this way?

- Why did the photographer choose to have only one image on a spread? What meaning is he or she trying to create?

Most photographers create their books very intentionally. They play with the ordering of the images and the pairings to create a certain emotion, mood, and meaning. And the more cognizant we are of this when we are looking through photography books, we can better appreciate the book.

Also if you work on your own photography book (I highly recommend self-publishing services like Blurb) think about the meaning of pairings you have in a book. You can put together two images that have a similar meaning or aesthetic look. Or you can put two images that have a strong contrasting emotion or mood (happiness on one side, sadness on the left). Or you can play with combining different symbols to create a whole new meaning all-together.

4. On making change through her photography

Zoe Strauss’ images are very socially conscious– and they say strong messages about her local community. She brings beauty to certain people and locations– while also making criticisms of America through her work. Strauss shares more of her thoughts on the power of photography to make change in the world:

“I think that art provides the ability to make change. I think there are different means at getting at reflection. Photography as a medium is able to provide people with ideas. In the last couple of years there has been such a shift in technology and the access that people have. I think the Abu Ghraib pictures are possibly the most important photos of the last 50 years in some ways because it has changed the way we have access to images, and who makes the images and where they go. That being said, I think the medium has a lot of different possibilities. In terms of art, there is a possibility to provide someone with an image that will cause them to have a shift in their thinking, not necessarily to change their thinking but the possibility to think about things in a slightly different way. I don’t think that is realistic all the time, but that’s what I work toward. It’s not always successful, but it’s what I am plugging away at.”

Takeaway point:

I think as street photographers, we are all trying to create certain messages and meanings through our work. We are trying to show a part of social reality to our viewers. And sometimes our motives are to show the beauty of the world, the sadness of the world– or something totally different.

Regardless what kind of message you are trying to make through your photography– we do have the power to change the mind of the viewer. The change can be very small and subtle– it doesn’t have to change the world on a grand and global scale.

The impact of your photography can be as simple as having your viewers appreciate the beauty of everyday life. Or if you photograph poverty– you can make your viewers feel more grateful for the things they do have in their lives (rather than worry about “first world problems”).

Think about what kind of ideas you can provide in your photography– and present it to your viewers and the rest of the world.

5. On blogging and photography

Not only is Zoe Strauss a prolific photographer– she is also a prolific blogger. Her blog is quite active– where she shares images, poems, and other thoughts in her mind. Strauss shares why blogging is so important to her:

“I could care less about my website, I feel like those images are very static. The blog is about the transparency of my process, the many things that go into making the photos, how my life is an integral part of my work and they both constantly inform one another, they are not separate.

Transparency is something that is very important to Strauss’ work. And she achieves this transparency of showing the image-making process through her blog:

“The blog is an important aspect of the I-95 project [as I wanted] to have transparency throughout the course of the whole project. I feel it’s important to see that these images are not made in a vacuum, that they come from a process. I often feel like there is a separation when it comes to fine art and when the finished image is presented it is something that is very removed from what the actual moment was. It is an important part of my process [to show] the background of how this image came about and a record of my train of thought.”

If you are interested to see more of Strauss’ photography process– follow her on Flickr, where she uploads unedited photos she is currently working on, in a “stream-of-conciousness” fashion.

Takeaway point:

For me personally, blogging is a huge part of my life and my photography. I love to write and share articles on photographers who have inspired me (like Zoe Strauss and countless others) while also creating some sort of online street photography community. Even though I still have a lot to learn in street photogrpahy– I love sharing what I have learned along the way. My aspirations with the blog are to share useful information about street photography, to connect other street photographers with one another, and also promote the genre to the rest of the world.

Strauss also sees blogging as an inseparable part of herself and her photography. Her transparency and “down-to-earthness” is what really makes her appealing as well. She doesn’t act like a pretentious “know-it-all” photographer (even though she has recently joined Magnum as an associate). Rather, she keeps it real– and shares her photographic process openly with the rest of the world.

If you don’t have a photography blog, I highly encourage you to start one. It can be on WordPress, Blogger, Tumblr– or whatever platform of your choice. Share your thoughts on photography. Share your working process. Share your Lightroom presets. Share inspirational quotes or words from other photographers. Share the sites of other photographers whose work inspire you. Share your thoughts on photography– and your personal journey.

Make your blog open, personal, and transparent. Your blog will help you stimulate new ideas in your photography, and also connect you with potentially millions of people all around the world.

6. On gender and photography

Zoe Strauss has some pretty outrageous photos– one of two guys at a parade showing their tattooed penises– and another of a nude man in his hotel room. When I first saw those images, I thought to myself: it must be easier for Zoe Strauss as a female to take those kind of photos.

Zoe Strauss shares some thoughts in-depth about gender and photography– and how sometimes being a female makes photographing certain situations easier:

“I think gender is something that is happening constantly in the world. We are always trying to navigate it and figure out how we interact with people in relation to gender. I think that people generally feel less threatened by a woman, I think that is something that is realistic, and I think that often allows me to go places that would be difficult for a man. I think realistically that it would be a different interaction, I don’t know, if I would be like, “Hey dude, come on into my house, woo hoo!” I think in a lot of photographs people respond specifically to the photographer, and because I am a woman I think it is an integral part of it and some of the shots I have, particularly nude shots of men, are ones that are more likely to have happened because I am a woman and it would have been a lot less likely that these guys would have been happy to share their penises [with] a man.

Takeaway point:

If you are reading this and you are a female street photographer– that is wonderful. I think people are generally less intimidated by women street photographers. After all, women tend to be less threatening than men (in general). Not only that, but I have found that women generally have an easier time than men taking photos of children (women usually aren’t perceived as potential pedophiles).

Of course it can also be difficult as a female photographer– I have heard of stories of men taunting female photographers. And some female photographers might not feel as safe walking around in shadier neighborhoods by themselves.

I think it is important for us to consider our gender when it comes to shooting in the streets. For example if you are a man, know that it might be more difficult to photograph children and other women in public. If you are a female, you might have less problems doing this.

As a male, I personally haven’t had many issues taking photos of children or women. I just try not to be sneaky about it– and do it quite openly. If you photograph with a telephoto lens with a black trench coat on, it might look suspicious to outsiders.

And if you are a female street photographer– use your gender to your advantage. Know that you are less threatening in general, so use that to build up your confidence when taking photos in public.

At the end of the day though– don’t worry too much about your gender. Male, female, transgender, whatever you may be– just go out with a big smile, show positivity, and shoot openly.

7. On dedicating your life to photography

One thing that quite impressed me about Zoe Strauss was how passionate she was in her photography– to the point that she decided against having children:

“In my mid-thirties my wife and I decided that we were most likely not going to have children. I’d always been certain I wanted children but suddenly found myself going full force at this all-encompassing, life-filling project, and I decided I didn’t want to stop; I would forgo being pregnant and possibly ever having children. It was a painful decision to make, but I was moving forward like a full-throttle freight train, and I felt strongly I had to choose one or the other. I picked I-95.”

Takeaway point:

I’m not telling you to all go out and decide not to have children or get married in order to fully dedicate yourself to photography. However the reality is most photographers or artists who create truly outstanding bodies of work have a difficult time balancing their personal life and work. Of course there are many exceptions of photographers out there who can balance the both.

I think the takeaway point is that great projects often consume your life. And unfortunately we can’t have everything in life we want. We all can’t be super rich, work only part-time, have an amazing and engaged family life, and also be a world-class photographer. Life is short. We have to pick what to keep in life, and what to leave out.

Ways you can practically apply this: if you want to take your street photography more seriously, think about what you can cut out of your life. Whether it be other hobbies, or other types or genres of photography. I don’t think my street photography really took off until I decided against taking photos of weddings, landscapes, macro, babies, etc.

I also encourage for you to focus on creation over consumption. Meaning, create more photos– rather than just consuming media. Spend less time on the internet, on social media, on photography forums, watching television, or extracurricular activities that don’t mean that much to you. Focus on your photography, put in your 10,000 hours of practice, and create great work.

8. On captions

In Strauss’ work, she often has short descriptive captions for her work. Such as “Daddy Tattoo” or simply the name of her subject.

Many photographers have different conventions in terms of titling their work, or adding captions to their work. Zoe Strauss shares a bit more of the meaning of captions in her work. She starts off first by the importance of referencing the history of photography:

“I think there are a number of things that go into the text photos for me. One being that I am very conscious of the history of photography

it’s important to me to reference it and to talk about how photography is still a burgeoning art; it’s important to pay homage to these specific forms that have essentially just occurred and which we are still working through.

Strauss continues by sharing in her I-95 project, she wanted people to both read the text and look at the photos– creating a “different way of seeing”:

“Another big part of it in terms of the I-95 project and the installation is that I want people who walk through it to get a sense they are reading these images. So the literal act of reading is something that is really important in moving people back and forth when seeing the images, it creates a different way of seeing.“

Furthermore, Strauss shares how she likes having some of her captions as incomplete– which still gives some room for her viewers to make an interpretation:

“Personally I am very drawn to text, I am interested in reading and language, I am interested in more than one meaning with the text and how we can make our own meanings out of these things. Many of them are incomplete statements but they are solid and they say enough for a person reading it to create their own narrative without telling them the whole story.“

Takeaway point:

Personally I used to title all of my photos– but now I simply include the location and the date. I don’t want to suggest any stories to the viewer. I want the viewer to come up with his or her own story or interpretation of the image.

Of course this is only my thoughts and feelings. Strauss adds a bit more description into her images via the caption, which works well for her. Considering that she is interested in reading text herself– she likes giving context to her images.

So I think at the end of the day, title or caption your photos as you would like. I generally cringe when I read titles which are a bit cheesy like “Darkness”, “Loneliness”, or “Despair”. But your work is your work. Title your images in a way in which you think your viewers will get the most out of them.

Conclusion

Zoe Strauss is a unique photographer– who is very open and transparent about her work. Coming from a working-class background herself, she is able to really connect with the people in her community through photography. All of her work is community-oriented, including her influential I-95 installation project/public exhibition.

Strauss makes herself vulnerable to her subjects, and they open up to her. They let her take intimate photos of their lives. And Strauss certainly has a strong sense of morals– she wants her subjects to like the photos she takes too. She shows her subjects the photos that she takes, and deletes them if her subjects don’t like them.

I think as street photographers we can all learn a thing or two from Zoe Strauss in terms of being more humanistic. To care about our subjects, our interactions with them, as well as our community.

Videos

Below are some insightful videos of Zoe Strauss and her work:

Studioscopic: Zoe Strauss

TEDxPhilly – Zoe Strauss – An Incredible Decade

Zoe Strauss and Steve Earle in conversation, Jan 28, 2012

Fader TV: Zoe Strauss

Interviews/Features

- Zoe Strauss Inteview on Photo Eye

- Zoe Strauss Interview on Lemon Hound

- Zoe Strauss on Art News

- Zoe Strauss “America” book Review

Zoe Strauss Social Media Links

- Zoe Strauss I-95 Show Photos on Flickr

- Zoe Strauss Blog

- Zoe Strauss Flickr

- Zoe Strauss on American Suburb X

Books

1. Zoe Strauss: “America”

“America” is Zoe’s first book– and one of my favorite color photography books. It is also incredibly affordable at only $21 USD. You would be crazy not to get it.

For a preview, you can see the entire book spreads on Zoe’s Flickr page here.

2. Zoe Strauss: 10 Years

“Zoe Strauss: 10 Years” is a newer compilation of Zoe’s best work in her photography career. Also incredibly affordable at $22 USD.

You can see more of Zoe Strauss’s Photos on Magnum here.