One of the most valuable books I currently have in my library is Magnum Contact Sheets. It is a book that was put out by Thames and Hudson in the last year or so, and contains over 139 contact sheets from 69 Magnum Photographers.

For those of you who are not familiar with contact sheets, they are a direct print made from a roll or sequence of images of film. Before the days of digital, they were an invaluable tool to photographers to quickly look through and edit their work (choosing their best images).

The book is a hefty behemoth full of knowledge, insights, and philosophies of the Magnum photographers within. I know that not everyone has the ability to access the book (as it is sold-out almost everywhere across the world and it is quite expensive) so I wanted to make this post to share some of the insights I learned from the book. I hope this post will help you and your personal journey in photography!

What is a contact sheet?

To clarify, a contact sheet is a direct print of a roll or sequence of images shot by a photographer on film. In Magnum Contact Sheets, the editor Kristen Lubben goes more in-depth:

“This contact sheet, a direct print of a roll or sequence of negatives, is the photographers’ first look at what he or she captured on film, and provides a uniquely intimate glimpse into their working process. It records each step along the route to arriving at an image– providing a behind-the-scenes sense of walking alongside the photographer and seeing through their eyes.”

As Lubben explains, the contact sheet is a tool used by photographers in the days of film to look quickly at what they captured. The equivalent to digital nowadays is Lightroom, which allows photographers to see the contents of their SD card of what they shot during a certain period of time. However what makes the contact sheet unique is that it contains only contents from a roll of film (generally 36 shots), while digital can provide a “contact sheet” of hundreds upon thousands of shots.

Why are Contact Sheets Important?

As Lubben explained in the blurb previous, contact sheets give a “uniquely intimate glimpse” into the working process of each photographer. If you look at the contact sheets of different photographers, you will see how differently photographers shoot.

For example, some photographers (like Philip Jones Griffiths) are famous for being very conservative and economical with their film – only taking about a shot per scene. Another example is Chien-Chi Chang, who is working on an ongoing project in which he takes single, isolated shots of a particular scene. He explains:

“Usually when you shoot, you work the image. You shoot a strip of film and pick the best. I work it, too, but in my heart or mind… I don’t really care about the “before” and “after anymore.”

Most other photographers generally tend to “work a scene” and take multiple shots of a scene, at different angles, and at different times to capture what Henri Cartier-Bresson called “the decisive moment”. At times these “decisive moments” happen by chance (by the photographer being at the right place at the right time), while other times photographers work hard to extract a certain moment from a scene.

Lubben describes the importance of the contact sheet in today’s digital age:

“The contact sheet, now rendered obsolete by digital photography, embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: the sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

With the advent of digital photography, contact sheets are virtually obsolete– only really being used by a few working photographers who still work on film. In Magnum some of the photographers who still use contact sheets include Bruce Gilden, Chien-Chi Chang, and Larry Towell. However they provide a different experience to photography, that leaves a trace of a certain scene or memory – something that can be revisited over and over again.

Of course you can still do the same with digital by going back to your archives, but generally a contact sheet (on a piece of paper) is easier to re-visit.

Why Did Thames & Hudson Publish Contact Sheets?

Contact sheets are a thing of the past and most photographers starting off in digital (myself included) aren’t aware of the importance of them. Lubben describes why they decided to work on the book:

“Through the work of Magnum photographers, this volume traces the development and demise of a way of working that was so ubiquitous as to seem an inevitable and inextricable part of the process of photographing: the use of the contact sheet as a record of one’s shooting, a tool for editing, and an index to an archive of negatives.

“…Throughout, the intent has been to give a reader a sense of how each photographer initially encounters his or her own work, and to provide a window into their private editing and selection process. While editing programs that create a simulation of the contact sheet from digital images are widely used today, they are a fundamentally different entity– a translation of what a photographer has seen, rather than its trace— and we have chosen to omit digital work from this volume*. In this sense, the book functions, in the words of Martin Parr, as an ‘epitaph to the contact sheet’.

(*Exception is Mikhael Subotzky, who shoots in color film but edits the film digitally.)

I have taken photographs for around 6 years, and although I love the convenience and accessibility of digital photography – I wonder how scholars studying photography will have access to digital archives. Is Lightroom still going to be used in the future? How are we going to deal with issues of compatibility with RAW files in the future?

It will be much more difficult to index the working styles of photographers, and seeing the “before and afters” of famous images shot in history. I am glad that Thames & Hudson put out the book, which will be a valuable resource for the photographers now and here to come.

Why are Contact Sheets Difficult to Come By?

Contact sheets (especially from famous photographers) are notoriously difficult to come by, as they are generally a “private diary” of photographers. Most photographers don’t like to reveal or show the “behind-the-scenes” work behind their most famous images, as it can be very personal. Lubben explains:

“Often compared to an artist’s sketchbook, contact sheets are certainly more unrelentingly all-inclusive than that analogy would suggest. There is no removing or erasing the unsuccessful steps on the way to the final product– each twist and turn, each decision, is recorded, allowing viewers to see along with (or perhaps second-guess) the photographer.”

There is generally a myth behind “the decisive moment” as it generally takes a photographer several attempts at working a scene to get a certain memorable shot. To show contact sheets of a photographer “demystifies” the magic of photography. However I love the demystification of certain famous images, as they can be studied by students of photography and show that the great photographers that came before us are also “regular human beings” (just like you and me).

An interesting anecdote is how Henri Cartier-Bresson himself (inarguably the most famous photographer in history) even destroyed his early work. Even HCB had to start somewhere. Lubben states:

“Cartier-Bresson famously cut up his negatives in 1939 as he would ‘cut his nails’, preserving individual images and sequences that he deemed successful or valuable and discarded the rest’. Cartier-Bresson states this about sharing contact sheets:

“A contact sheet is full of erasures, full of detritus. A photo exhibition or a book is an invitation to a meal, and is not customary to make guests poke their noses into the pots and pans, and even less into the buckets of peelings…”

Beven Davies also explains the reason why he doesn’t like to look at his contact sheets, but understands the difficulty of photography:

“Contact prints are the proof that I did something wrong. Perhaps I could have moved the camera two feet this way or that, or waited until the sun was in a slightly different position. They show how difficult the medium can be.”

Generally, contact sheets aren’t meant to be open to the masses for “public consumption” – very much like how one wouldn’t want their personal diary to be shared with the masses. Lubben writes:

“The illicit quality of the contact sheet is the source of much of the viewer’s fascination with it. Like reading someone’s diary or looking into their closet, the contact sheet is not meant for public consumption.”

For this article I will continue to provide quotes and anecdotes from Magnum Contact Sheets to help you better get an in-depth understanding of the philosophies of photographers and contact sheets and their ways of working. To make this long and detailed article easier to read, from this point forward I will break down what I learned from the book:

1. On demystifying the seemingly magical quality of photography

Below are close-ups of the contact sheet from the Seville contact sheet:

I think one of the most difficult challenges I faced when starting photography was living up to high expectations. I remember looking at the classical work of Henri Cartier-Bresson & Andre Kertesz and asked myself how I would ever be able to create work that was up to their caliber.

I would look at the work of other master photographers and sense that they had certain magic and that they were super-human. However over time, I realized that these master photographers were regular human beings – and had to also work hard to get their images. Martine Frank from Magnum, former wife of Cartier-Bresson, explains this more in-detail:

Martine Frank: “I have certain misgivings about letting my contact sheet be published but in final analysis I realize that I am curious to see how other photographers work. One rarely expresses in words all the random thoughts that run through one’s head except maybe on a psychoanalyst’s couch, and yet the contact sheet spares neither the viewer nor the photographer. I feel that by allowing myself to be violated, and by publishing that which is most intimate, I am taking the very real risk of breaking the spell, of destroying a certain mystery.”

Photographers like Frank are aware that releasing contact sheets into the wild does demystify and “break the spell” of amazing images shot in history. However reading contact sheets allows regular viewers and photographers to see the working styles of famous photographers that put them down-to-earth.

2. Famous photographers also get disappointed when looking at their work

Street photography is very hard. It is rare that you can take an image that has a perfect harmony between content and form.

I very rarely get good shots. I currently shoot around 50 rolls of film a month (about 1,800 shots) and would say I only get a good shot once a month, and one great shot a year. I remember feeling this constant sense of disappointment that my “hit rate” was so low, and whenever reviewing my images from my days shooting I would feel like giving up. If I do my math correctly, my “hit rate” is only at 0.05% (a very low standard).

However it seems that the sense of disappointment that I feel isn’t just exclusive to myself – but also to accomplished photographers. Elliott Erwitt and David Alan Harvey from Magnum share their sense of disappointments:

Elliott Erwitt: “It’s generally rather depressing to look at my contacts– one always has great expectations, and they’re not always fulfilled.”

David Alan Harvey: “I hate looking at my work. I delay it for as long as possible… I just know that it won’t live up to my own expectations.”

Therefore when looking at your own work, set realistic expectations for yourself. Street photography is one of the most difficult types of photography out there, as there is so little you can control. You can’t control what people wear, how they walk, or the background. The only two things you can control is your positioning in the scene, and when you hit the shutter. The rest of it is based on opportunity and being “at the right place at the right time”.

I like the idea of setting reasonable expectations of yourself (such as getting 1 good shot a month and 1 great shot a year). Of course what constitutes “good” and “great” is subjective by different photographers – but by setting these standards it will keep you motivated to work hard, and realize how difficult creating a good image is.

For his seminal book, “The Americans“, Robert Frank shot 767 rolls of film which yielded about 27,000 images. Frank edited that down to about 1,000 work prints, spread them across the floor of his studio to first glimpse at them. Over time he started tacking the ones he liked most to his walls for a final edit. After a year and a half of work in his project, Frank chose just 83 images for his entire book (83/27,000=.3%). Only .3% of the shots of the photographs Frank shot in total made it into his book.

3. Judge yourself by your contacts, not your final shots

As photographers we tend to only showcase our best work. We rarely post more than 10 photographs from the same scene, as we don’t want to show our “failed attempts” at creating a good photograph.

It is interesting to note that in the early days of Magnum, photographers were judged by their contact sheets (to get accepted) rather than their final work prints. This practice has continued until around 2000 when digital photography started taking over.

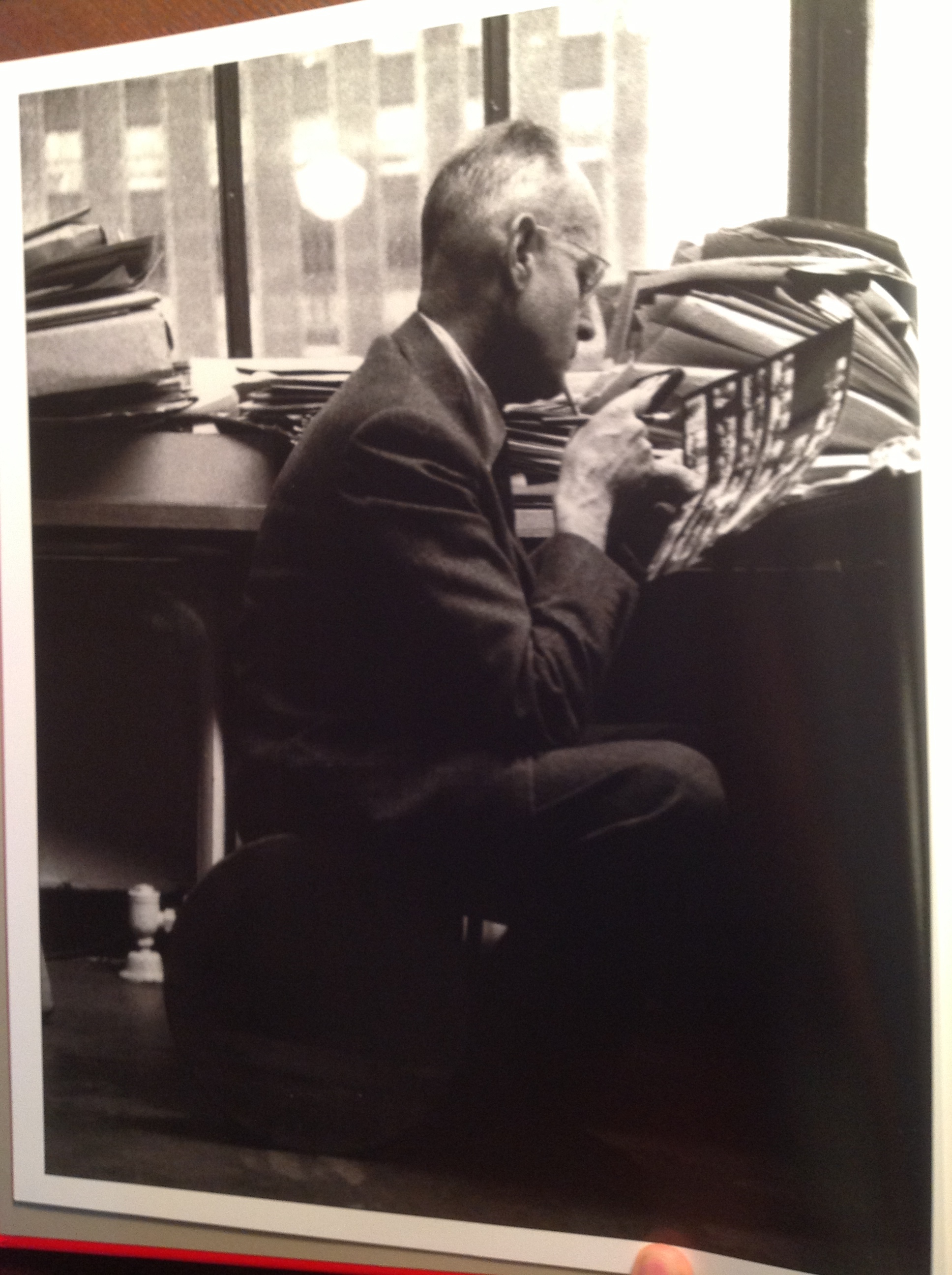

Why did Magnum do this? It was due to the fact that a photographer’s admission into Magnum wasn’t due to just their final images, but their working style and how they thought when taking photographs. John G. Morris, one of the editors for Magnum, shares: “That’s so you can see their thinking.”

A peculiar thing that Cartier-Bresson would do is look at the contact sheets of photographers who were applying– and would rotate the contact sheets from all different angles- and assess the formal composition of the images. Rene Burri explains this practice that Cartier-Bresson would do:

Rene Burri: “He always turned them all around and upside down. It became like a sort of dance. Strangely he didn’t want to look at the picture!”

My good friend and colleague Adam Marelli who is very familiar with the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson also shared this with me. He explained to me that once you flip images upside down, they become abstractions and the content of the photograph doesn’t distract you from assessing the formal and compositional elements of an image. One tip that he gives (and which he also does at times) for digital is making his image thumbnails really small in Lightroom and flipping them upside down to judge his own images.

Rinzi Ruiz, also a good friend and fellow street photographer from Downtown LA shares that he judges the formal elements of his images by making the images on his screen full-screen, and stepping away half-way across the room to look at his images and squint. Rinzi was classically schooled in design for his undergraduate and also used similar techniques when it came to his other artistic work.

David Hurn from Magnum also shares a story of when he first joined Magnum, he would learn a great wealth of knowledge from studying the contacts of other photographers:

David Hurn: “When I first came into Magnum, I learned an enormous amount by pursuing shelves of books of contacts from Henri Cartier-Bresson, Marc Riboud, Rene Burri, Elliott Erwitt, etc. A feast to be absorbed, night after night, in the Paris office on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honore”

As a takeaway point, realize that photography isn’t just about your final images- but the hard work that goes into them. I encourage you to re-visit your personal favorite images and see the before and afters of the shot. Think to yourself: how long did I have to wait for a shot? Did I “work the scene” and create the shot, or did it serendipitously come to me? Did I take too many scenes of a shot, or not enough? Thinking these things will help you better understand your own working style in photography.

4. Realize the strengths & weaknesses of working in film or digital

I started photography on digital, and am really glad that I did. It saved me a lot of time, headache, and money to learn the technical ins-and-outs about photography and more about how I liked to work.

I recently sold off most of my digital cameras and now more or less shoot exclusively with my Leica MP and 35mm lens. After making the switch it has helped me tremendously in my photography, in which I explain more detail in this post: “Why Digital is Dead For Me in Street Photography“.

One of the things that are misunderstood about the post I wrote is that people think I mean to say that film is better than digital for street photography. To clarify, I don’t mean that at all. For me personally shooting film has helped me approach street photography in a unique way that has helped me in my photographic journey. However I don’t mean to put down shooting street photography in digital in any way. Film & digital both have pros and cons, as I will explain more in-depth.

We are all familiar with the pros of shooting digitally. The convenience, instantaneousness, and the saving costs (not paying for film or developing). However there are also cons that are involved, which some Magnum photographers explain:

a. The Difficulty of re-visiting work

One of the first issues is the pressure that working digitally can put on us, and the difficulty of re-visiting work. Pellegrin explains:

Paolo Pellegrin: “The workload with digital has certainly doubled with fieldwork. You have now to photograph, edit and send your images on the same day. You go back to your car or hotel room to download, caption and transmit your work. It’s much more immediate and it becomes much more difficult to revisit the work.”

b. The process of photography becomes less connected

Although there is a great sense of independence working independently in photography, shooting with film and working with contact sheets in the past allowed for more collaborative processes. Meiselas explains:

Susan Meiselas: “Digital photography can permit greater sharing in the field, but cuts out collectively at the other end. Fewer people share the whole process. It used to be that you sent raw film in and often the Magnum editorial or another photographer would take a look at the contacts.”

Although the advent of digital photography and social media allows us to share with more people all across the world than ever, I have noticed that the feedback and comments we get are very shallow compared to getting critique and feedback in-person. If you have a Flickr or Facebook you know that after a while, getting a ton of “Likes” and “Favorites” and getting comments like “nice shot” don’t really amount to much.

Sitting down with another photographer face-to-face and sharing your work (and especially your contacts sheets) allows you to get real-time feedback that is much more thorough and in-depth. If you don’t have anyone in “real life” that you are able to collaborate with, I recommend you to try to find some local photographers in your area whose work you admire to work with and get feedback from.

c. The change of pace of photographing

Jim Goldberg, from Magnum talks about how switching from film to digital is changing the pace of photographing. He shares that having to reload his film forces him to pause and reflect in the shooting process “to reset, rewind your thinking. The opportunity for that forced pause has been lost.” As has the “containment of a roll of film”.

d. The loss of intensity while shooting

Another insight I gained is that shooting with film gives you more intensity when you shoot. After all, you don’t really know what you have at the end of the day, so you will want to work a scene quite hard to ensure that you “got the shot”. When I used to shoot digitally, once I saw a decent photograph at the back of my LCD, I would often move on. Meiselas explains:

“I still think not knowing what you ‘have’ at the end of the day with film gives strength of the intensity when you work. It is a mystery and surprise. Now everyone spends more time looking at their screens, first on the camera and then the computer.”

e. Lost is the time to mentally recap on your day

I travel quite a bit for teaching my street photography workshops and to shoot. When I shot digitally, I would often stay up late at night downloading my images into Lightroom and reviewing them everyday. With film, I am not physically able to do so — so I have more time to either relax, spend more time enjoying my company with my friends, or to recap on the day of shooting. Gilles Peress from Magnum shares his experiences:

“With film you kept track in your head of what you were shooting, and evenings could be spent on a mental recap of the work you had made: the technical demands of digital editing in the field, at their worst, mean ‘less reflection, less intelligence, less thinking time‘.

Of course the things that I mentioned above about shooting in film can be re-created when shooting digitally. However personally I have found that although you can mimic certain aspects of shooting film (limiting yourself to a roll of film by using a 32mb card, not by chimping, and waiting on your images before reviewing them), there is still a constant urge to do so. Shooting film has helped me resist those temptations and focus more on my photography, editing, and reflecting on my days taking photographs.

I don’t mean to say that you have to shoot film, but if you have started photography in digital and haven’t experienced shooting film, I highly recommend trying doing so.

5. Be self-critical and brutal with yourself in editing

I personally believe that the editing part of photography (choosing your best images) is more difficult and than the photographing. To choose between your images is like choosing between your children — you want to keep them all but at the end of the day you have to choose one image from the scene that best describes it.

I think it is also important to be self-critical and set high standards in terms of what you show. In the age where images flood the internet by the trillions, less is more. Quality triumphs over quantity. David Hurn from Magnum shares some of his thoughts on being self-crucial in photography and learning from your contact sheets:

“The contact sheet is a valuable instructor. Presumably, when a photographer releases the shutter, it is become he believes the image worthwhile. It rarely is. If the photographer is self-crucial, he can attempt to analyze the reasons for the gap between expectation and actuality. How does one think? Could the image be improved by moving backwards or forwards, by moving to the right or left? What would have been the result if the shutter were released a moment earlier or later? Ruthless examination of the contact sheet, whether one’s own or another’s , is one of the best teaching methods.”

By ruthlessly studying your own contact sheets (on film or digitally) will help you better evaluate your own work, and decide how you can further improve your photographs in the future.

Changes in your positioning, your framing, or when you click the shutter is often difficult to decide when you are in the heat of shooting on the streets. It is much easier to figure out afterwards in the editing portion. Therefore try to internalize enough of these self-critical thoughts and when you are out shooting, it will become more second nature.

Bruce Gilden also shares how he is a tough editor of his own work:

“I am a tough editor of my work, and usually when I look at my contacts I find that I can go as many as fifty rolls without getting a good photo. But when I looked at this roll, I had not one but two of my best images ever of New York City. What a coup!”

Getting good photos in photography doesn’t follow a linear pattern. Sometimes (like Bruce Gilden) we can go 50 rolls without getting a single good shot, but at times we can get more “keepers” on one roll or day out shooting. Like street photography as a metaphor like fishing: Sometimes when you go fishing you catch a lot of fish, and other days you fish you can catch nothing.

6. Suggestions on editing your best work

There are many approaches that photographers use when editing their own work and choosing what they believe is the “best” shot of a sequence.

Leonard Freed from Magnum shares how he edits his images to the single most powerful photograph in a frame:

“It can be difficult to make a decision because you can like this frame for this reason, and that frame for that reason. Each photograph has its particular strength. But you only pick one. One has to represent all. So I am always trying to put everything into one image: the statement, the foundation, the composition, the story, the individual personality – all of that together into one image…”

Henri Cartier-Bresson likens the process of editing like wine in a cellar. You only want to share your best wine with your close friends and family, and the best wines are often aged for a long time. This is what Cartier-Bresson said:

“Pulling a good picture of out a contact sheet is like going down to the cellar and bringing back a good bottle to share.”

Nikos Economopoulos also shares a story of one of his best-known images, shot at the Central Railway Station in Tirana, Albania in 1991:

“I remember standing beneath the shelter of a shed as the man approached me in the rain. Choosing to take the photo was done mostly with a photographic criteria in mind.

One always has subject matter; it’s a matter of selecting the form that works best. Usually one element strikes me initially, and then I start building around it. The rest of the elements are fluid, and it is in this fluidity that I try to capture and understand what I see. The man with luggage walking between the two trains is the shifting element; what interests me is his relationship with the surrounding context and the changing scale.”

With Economopoulos he discusses first choosing the subject matter (who or what to take photographs of), and then trying to select an image that have compositional elements, context, and scale which suits the photograph the best.

In the winter of 1995, Eli Reed visited Rwandan Refugees in Benaco, Tanzania and took many photographs over the course of several days. When faced with choosing his best images, he tries to edit according to his gut feeling:

“Over three or four days I shot something like forty rolls of film. When I edit, I go for a gut, instinctual feeling. I started editing when I got the film back a day or two after I returned to the states. You are so aware of what you saw; the experiences that reflect in your mind. You don’ really forget the people and what they are going through. So I wanted to work on it immediately. Like anything else, when you’re trying to put down what you witnessed, you go for the pictures that speak to you.”

Larry Towell also echoes Eli Reed’s sentiments on editing by remembering the feeling that he had when taking a photograph:

“When I look at a contact sheet, I try to remember the feeling I had when I took the frame. The memory of feeling helps me edit. Art for me is really simple. IT’s when a feeling overcomes you and you convey your feeling with symbols. In photography the symbols are the thing itself.”

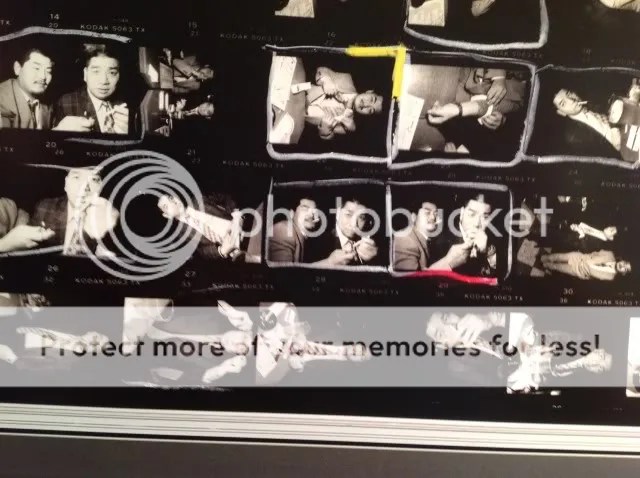

In a story by Bruce Gilden, he explains how he chose one of his favorite photographs of the Yakuza in Tokyo, 1998 based on what works form-wise and emotionally:

“An image I took then became one of my favorites from the Japan series. It was taken early in the evening at a coffee shop in the Ginza area of Tokyo. As we were talking, the gentleman at the rear lit the other yakuza’s cigarette. I like bad guys, and cigarettes are one of my favorite photographic props. So at that moment, right there in front of me, I was offered a great combination of three elements that attract me visually: cigarettes, smoke, and underworld characters. The scene looked wonderful, so I asked through my translator if they could do it again, and they agreed. I thanked them and I went on photographing. The lighting of the cigarette lasted at most another minute.

When I look at a contact sheet, I go in order from no 1 to no 36. I mark the ones I like, and unless something really jumps off the page at me, I go over them again to see which is the best one. With my personal work, I only print what I think is good. When something jumps off the page, it’s easy. That photograph jumped off the page. It worked form-wise and emotionally. To me, the photograph says a lot about the hierarchy in Japanese society, with the underling lighting the cigarette of the person above him, and i like the wary eye that the ‘boss’ gives the photographer”.

When you take a large amount of photos, is often difficult to edit down to your best shots to include in a series, exhibition, or book with a limited amount of space. For Mark Power’s project, “The Shipping Forecast” he shot over 1,000 rolls of film and had a difficult time getting feedback and choosing his best images. What he discovered helped in the editing process for him was to really consider what the work was about and why he was photographing the project:

“During the four years I spent making The Shipping Forecast I exposed nearly 1,200 rolls of film, which amounts to 14,000 individual pictures. Editing this down to a manageable number was a major exercise. I had advice from several people whose opinion I respected, but this only served to confuse me more. So instead I asked myself what the work was really about, and the answer was far clearer: it was about my childhood.

In the end, The Shipping Forecast doesn’t depend on outstanding individual pictures, but instead on its collective strength.”

Therefore when you are editing your work, it is very important to have your friends and peers to help give feedback. But in the end, don’t just consider what images from your project may be the strongest necessarily, but what go together well in terms of “collective strength” and what message you are trying to convey to the viewer.

A unique approach in shooting film and editing digitally is from Mikhael Subotzky. He shares his approach and the reasoning behind it:

“When I was a student, I worked with both 35mm film and digital cameras. I would edit the black-and-white 35mm work on handmade contact sheets, and the digital color work on the computer. In the darkroom, I was struck by how one’s ‘gut feeling’ about an image changed as it revealed itself– at first glance in the processed negatives, on the contact sheet, and then in a larger work print. I was often fooled into thinking that a negative looed like a better image than it actually was, and that an image on a contact sheet was worse than it actually was.

Editing digital work on the computer was like going straight to a work print for each frame – a fully formed image that can be looked at with two eyes. Despite the distorting effects of the backlit screen, I preferred this approach to editing tiny images through a magnifier. Later I returned to working exclusively with color film, but found it easier to replicate the digital editing process by scanning each frame I shot in low resolution”.

This is similar to the approach I have when working in color. Looking at black and white negatives is easy to judge composition and content, but it gets tricky with color negatives. Fortunately because I get all my color work developed and scanned at Costco, I import all of my images into Lightroom and edit my work digitally.

Takeaway point: Editing is a very personal process and a difficult one to do yourself. Make sure to always get enough feedback from peers that you trust, be self-critical, judge on composition & form, and think about why you are trying to show others the image. Realize that it is a very long process as well – and if you are ever in doubt about an image don’t be rushed to post it. Rather like a nice wine, let it sit in the cellar and age. And like HCB said, when your guests come over to your house make sure to give them the best one!

7. If you come upon a good scene, take lots of photos

I used to believe that the fewer photos you took when out shooting in the streets, the better. Also part of it is that when I saw a good street photograph opportunity, I would get nervous and only want to take one shot and get the hell out of there.

Now I have realized the merit of taking multiple shots of the same scene when shooting on the streets. Although there are a few photographers who are very conservative with their film and take only one shot of a scene (Philip Jones Griffiths for example), the vast majority of photographers take multiple shots of the same scene. If looking at the contacts of the Magnum photographers has taught me anything is that on average each photographer took at least 3-5 photographs of a scene if they thought it was meaningful or if they sensed a great photo opportunity.

For example in one of Elliott Erwitt’s most famous shots of the “Bulldogs” in 2000, he was walking around the streets of NYC with a fellow Magnum photographer Hiroji Kubota he saw a great photographic opportunity. After borrowing Kubota’s camera, he shot a full roll of film on the scene, trying to get the perspective just perfect to create an illusion of the man looking like a bulldog. Erwitt describes the story:

“I was out walking with my friend Hiroji Kubota around the corner from my studio on the upper west side of Manhattan, and i didn’t have my camera. I saw the situation and i said, “Could I borrow your camera?” And I borrowed his Leica. He was very generous and let me use it and I shot the whole roll of film on it.” [..] “Its a lot of pictures getting to the good one.”

It was that Erwitt deliberately worked the scene that on the last frame, he got his best shot.

Richard Kalvar, a Magnum photographer who is also very famous for his street photography shares the story behind of his most memorable images in the Piazza Della Rotonda in Rome, 1980- in which he also “worked the scene”:

“One day I came across my favorite raw material — people in conversation — just next to the foundation. An older man was speaking to a younger one (father and son, probably) in French, and reading out of a Michelin guide. The younger man apparently had weak eyes, and he wore thick glasses. I started my little dance, moving nearer and nearer, looking at all around the place and pretending to photograph the fountain or the surrounding buildings.

It’s generally not very easy to photograph people close up without their noticing (and getting suspicious or angry, or at least modifying their behavior) and rules are necessary .I like to be almost on top of my subjects, party because I’m nosy (or eyesy and earsy) and want to hear what they’re saying; partly because I want my slightly wide-angle lens (35mmm) to embrace them; and partly because I don’t crop my pictures so I try to control the composition, limiting what’s in the background.

I kept working the two guys, the spitting gargoyle and the background, grabbing pictures when I thought I wasn’t been seen. I started picking up on the water jet seeming to hit the young man in the neck, and I was ready when the miracle occurred and he suddenly turned his head up with that look that seemed to show some surprise. I had my picture, but that’s not why I stopped; I had reached the end of the roll!“

Kalvar shares this incredible story of how a he also got his most memorable image on the last shot in the frame!

Martine Franck also shares how she got one of her most memorable images from Le Brusc, Provence in France during the summer of 1976 and how important it is to be active and try to grab the shot:

“I had been commissioned by the newly created Foundation Nationale de la Photographie, then directed by Pierre de Fenoyl, to take a look at the French on holiday. My friend the architect Alain Capeilleres, asked me to photograph his recently completed swimming pool, which he had designed for his wife Lucie.

I distinctly remember running to get the image, while changing the exposure on my Leica M3 (I used a 50mm lens and Tri X Kodak film), wondering if shutting down to f.16 at a 1,000th of a second would be sufficient. The sunlight on the white tiles was so intense and almost blinding. I remember the man in the background doing his push-ups and waiting for him to be in a taut position. I only had time to take four shots and then the young boy in the hammock turned around and saw me, and the picture was gone.

That is the excitement of taking photographs on the spot. Intuitively one grabs the image, and an instant later the perfect composition has broken up and is no longer to be seen. It is only when you go back to your contact sheets that you can se how the scene developed in time, which is why contact sheets are a never-ending source of fascinating to those interested in photography. I chose this precise image because all the elements were in place. There was no second choice possible. It was evident from the start which image should be printed, and there was only one image.”

As a takeaway point, I recommend you to take more photos of a scene than fewer photos. Although I don’t recommend you shooting blindly and like a machine gun, don’t be shy. Take multiple photos while moving your feet from left to right, getting closer, or even taking a step back. Wait for different hand gestures (if a guy is smoking, get a shot of him inhaling the smoke and perhaps exhaling it). Try to shoot vertical images in addition to horizontals and vice-versa if possible.

8. Shoot to understand the world around you

One of the most eye-opening stories I read in Magnum Contact Sheets from Christopher Anderson, who took photographs on a boat with 44 Haitians who were trying to sail to America in 2000. Suddenly the boat starts sinking:

“Up to that point, I had not taken many pictures. Everyone on the boat knew I was a photographer, but it somehow had not felt right. It’s difficult to explain. But as the boat sank, David, the Haitian whom I had followed on this journey, said to me, ‘Chris, you’d better start making pictures. We only have an hour to live.’ And so, without much thought, I began making pictures.

We were saved at the last moment by a US coast guard cutter that happened upon us, but that’s another story. Much later on, back home safe, I reflected on this question: why make pictures that no one will ever see? The only explanation for me was that the act of photographing had more to do with the explaining of the world to myself than explaining something to someone else. The pictures were about communicating something about my experience, not about reporting literal information. This would be the single most transformative moment of my photographic life.”

After being saved, Anderson realized that when he was taking photos on the sinking ship, there was the possibility that nobody would ever see the images. He then had the realization that the reason why he took photographs. He took photographs to explain the world around himself rather than explaining it to others.”

Josef Koudelka, one of my favorite Magnum photographers, also recounts the story of taking photographs during the Prague invasion in Czechoslovakia in August of 1968. He took the photographs for himself, without the intent of publishing them:

“What was happening in Czechoslovakia concerned y life directly: it was my country, my problem. That’s what made the difference between me and the other photographers who came there from abroad. I was not a reporter. I didn’t know anything about photojournalism. I never photograph ‘news’. I photographed gypsies and theatre. Suddenly, for the first time in my life, I was confronted with that kind of situation, and I responded to it. I knew it was important to photograph, so I photographed. I took these pictures for myself, with no intention of publishing them”.

Personally I shoot street photographs with the intent of sharing with others my opinions and critiques about the members in society and shoot less for myself. However what I realized after reading this anecdote from Anderson is that there is a great importance of shooting for yourself in order to better understand the world around yourself.

Also the joy of shooting for yourself is that it takes a tremendous pressure off your shoulders and to remind yourself that photography is about the process, not necessarily the final image.

Nowadays I try to shoot more for myself, and enjoy the process of photographing – knowing that that most likely the photographs I make aren’t going to be interesting. But that small glimmer of hope that the photograph I take will be meaningful is something that also keeps me going.

9. Be free and carry little equipment

In today’s age, we are obsessed with cameras, equipment, and technology. Trust me, I fall victim to it as much as everyone else does. After all who doesn’t want to get the newest and shiniest cameras? I write a little about this topic on how to battle G.A.S. (Gear Acquisition Syndrome):

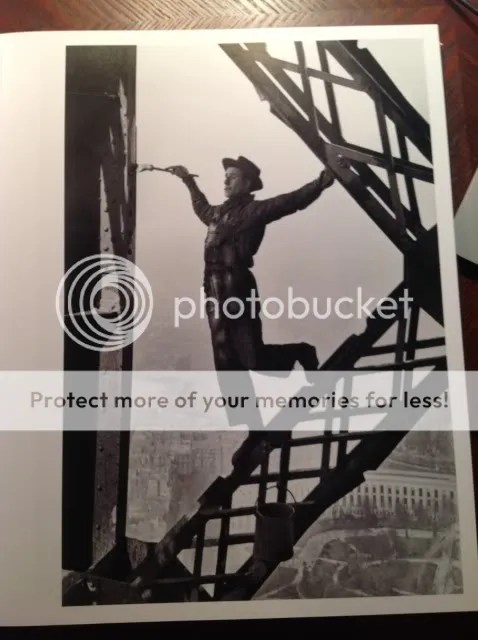

However there are benefits of carrying little equipment with you, and having constraints of having just one camera and one lens. Marc Riboud shares the story of his famous “Eiffel Tower Painter” photograph he took in Paris, 1953:

“In 1953, I leave Lyon for Paris. These are my first steps in the capital, and in photography. With my Leica and only one film, I’m strolling near the Eiffel Tower, which is being repainted. I suddenly noticed these paintbrush-bearing acrobats, and wishing to see them more closely… I walk up to the tower, maybe one hour of walking. Hanging onto the little spiral suitcase with only my 50mm lens, I can’t take close-ups or wide-angle shots, so I have only one choice left: that of the right moment. These constraints, these limited means, were my good luck in fact, and the choice was easy from this contact sheet, which isn’t always the case. The best photo strikes the eye, as the right chord strikes the ear.“

Riboud used the constraints of his 50mm lens to frame his photograph accordingly, and also to wait for the right moment in the scene. He continues by likening the care-freeness of the painter in his photograph to how photographers should be by saying, “I think photographers should behave like him: he was free and carried little equipment”.

10. Revisit your work

One of the beauties of contact sheets is that they allow you to revisit your work and sometimes find photographs that you didn’t notice before.

Eli Reed often goes back through his contact sheets to find photographs he may have initially overlooked. He also uses this as an opportunity to re-consider the lives of those that he photographed.

“I always go back through sheets- and you find images where you wonder how the hell you missed them, but you often don’t have the time to see everything the first time around. I also look back and wonder about the people in these images, and what happened to them. Somehow, because you can hold contact sheets in your hand, they stay with you longer; the images don’t go away.”

Whether you shoot film or digital, make sure to go back and revisit some of your old work. When I revisit my own work, I too find images that I took which were good that I may have initially overlooked. But not only that, but it gives me an opportunity to relive the experiences of the photographs I took. I have a terrible memory, but photographs of a scene help re-jog my memory and then everything becomes once-again vivid.

Also another suggestion is to have a trusted friend or fellow photographer to check out your contact sheets to see any photographs you might have overseen.

Conclusion

The anecdotes and quotes that I have provided in this article are just a very brief and small portion of Magnum Contact Sheets. If you want to continue your learning about different ways of working and editing, I highly recommend you to pick up a copy if possible. Although I have read the book several times, there is still much more that I have to absorb from the book as there is just such a great wealth of information contained within the pages.

Whether you shoot film or digital, use the insights from the book and the stories from the Magnum photographers to improve your personal vision and way of working in photography. Strive to create strong and meaningful work, but don’t be discouraged. After all, if the book proves anything is that even the world’s best photographers are doubtful of their photographic ability at times and do get frustrated too.

I did a lot of research and note-taking for the book, and if you are curious to see all of the notes and screenshots see them here.

Make sure to purchase a copy of Magnum Contact Sheets on Amazon and continue your own learning. The book isn’t cheap, but it will be a phenomenal investment for your education in photography (and is still cheaper than buying a new camera or lens!)

What other suggestions and feedback do you have about this article or on contact sheets in general? Share your opinions in the comments below!