All photographs in this article are copyrighted by Richard Kalvar / Magnum Photos

Richard Kalvar is one of the contemporary masters in street photograph, and also a member of Magnum. I have always loved his quirky and observant street photographs, and am quite pleased how active he is– especially on Facebook and the Magnum Blog. I gained a lot of insight about his work and street photography through his various interviews online. Read more to gain inspiration from him!

Richard Kalvar’s Background

How he got started

Richard Kalvar shares how he got started in photography:

“When I was a kid, particularly as I got a little older, I had a creative streak, which I didn’t really know how to channel. It mostly came out in screwing around with my friends when I was in high school and college. Then I dropped out of college, got the photography job, and learned about photography almost in spite of myself, because it was clear that I wasn’t going to be a fashion photographer. I wasn’t really interested in it.”

Kalvar shares how getting guided by mentors helped him in the beginning:

“I had the good fortune to be hired by a fashion photographer who had a broad knowledge of photography and was a smart guy and who introduced me to things outside of fashion photography. He showed me books. His name is Jerome Ducrot. He was a very good photographer. I left him after about a year. We had a big fight before I left, and then there was a big reconciliation, and when I left, he gave me a camera as a going away present.”

One of the biggest things that got Richard Kalvar started on his personal work was to travel through Europe on his own:

“I decided to go to Europe, just to travel around. It was while traveling around Europe, where the goal wasn’t to take pictures but just to have an adventure, that I started taking a few pictures, and by the end of the trip, I knew – I could feel that I was doing something with photography, and that this is what I wanted to do.”

He shares how the trip transformed his photography:

“I didn’t see any of the pictures I took. I saved my film, I sent some to my father, but I didn’t see it for almost a year. But I knew. I knew at the end of the trip that this was for me – that I’d found something that corresponded to the screwing around I used to do with my friends – I could express myself, express a way of seeing, a way of being, through photography.”

Career in photography?

Richard Kalvar shares how he transitioned into building a career in photography. He starts off from his humble beginnings:

“Back in the late sixties, times were different. Vietnam, the hippy era. A lot of people questioning things and so on. It was also a period in which the country was pretty rich. I came from a relatively poor family, but you didn’t worry about making a living. You could always get a job; drive a taxi, work in a restaurant. An awful lot of people, including myself, were more open to marginal activities.”

Photojournalism was the last thing on his mind, and he focused on expressing himself through his photography (than his career):

“I wasn’t really thinking about making a living as a photojournalist, I was thinking about being a photographer. From the very beginning, once I started to do it in a serious way, I was less concerned about a career in photography, working for magazines than in using it to express myself. I was fortunate enough to live in that brief period when you didn’t have to have a lot of money, and you didn’t have to worry about having a lot of money.”

Kalvar shares how he developed his interest in photography:

“I was able to develop what I was interested in, without having to worry about clients. Although I did get into the marketplace quickly, to make a living, since I didn’t want to drive a taxi or wait on tables, so I thought well okay, I’ll try to get some work in photography.

Joining Magnum

Kalvar shares how he got into Magnum:

“In the late 60s when I was in NY, I showed my work around. I went to see photographers like Andre Kertesz and Lisette Model and also a few people at Magnum. I left a portfolio up there. The people who reacted most were Elliott Erwitt and Charles Harbutt. When I applied in 1975, after leaving my old agency, Viva, it helped that I knew these people at Magnum.”

He also shares his first gigs, to just make a living:

“When I started out in France, I worked for various magazines. Women’s magazines, things about knitting, anything to make a living. I was taking my own pictures, working for whoever would pay me, and occasionally going off and doing something that was vaguely photojournalistic.”

Inspirations in photography

Richard Kalvar shares his inspirations in photography:

“I’ve always tried to photograph in my own natural way, but I can’t help noticing a connection with a bunch of mid-Atlantic (i.e., European and north-east coast American) photographers who do more or less what I’ve defined above: Robert Frank, Cartier-Bresson, Arbus, Friedlander, Erwitt… I find photographers like Paul Strand or Walker Evans admirable, but they leave me a little cold. When I first began in photography, I was liberated by seeing The Americans. Not that I wanted to take the same pictures as Frank, but I was excited by his way of “reacting to” rather than “showing”. “Showing” struck me as a little boring.”

Biography

Richard Kalvar Born 1944, Brooklyn, New York. Lives and works in Paris. After studying English and American literature at Cornell University from 1961 to 1965, Richard Kalvar worked in New York as an assistant to fashion photographer Jérôme Ducrot. It was an extended trip with a camera in Europe in 1966 that made him decide to become a photographer. After two years in New York he settled in Paris and joined the first Vu photo agency, and then in 1972 he helped found the Viva agency.

In 1975, he became an associate member of Magnum Photos, and a full member two years later. He has since served as vice-president and president of the agency. He has photographed extensively in the US, Europe and Japan. Richard Kalvar’s photographs are marked by a strong aesthetic and thematic homogeneity. His images frequently play on a discrepancy between the banality of a real situation and a feeling of strangeness that emerges from a particular choice of timing and framing. What results is a state of tension between different levels of interpretation, attenuated by a touch of irony.

In 1980 he had a one-man show at the Galérie Agathe Gaillard in Paris, and he has participated in many group shows. Specializing in daily urban life, Kalvar published Portrait de Conflans-Sainte-Honorine in 1993. The city of Rome has been the subject of an on-going personal project. A retrospective of Kalvar’s work was shown at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris in 2007, with a book published by Flammarion in Paris, London and New York at the same time.

Richard Kalvar is represented by Magnum Photos.

Lessons Richard Kalvar Has Taught Me

Below are some specific lessons Kalvar has taught me about street photography:

1. Good pictures come once in a while

One of the biggest frustrations in street photography is to make good photos. Good photos happen very infrequently. Richard Kalvar shares his experience looking at contact sheets, and when he can identify a “keeper”:

“It’s hard to put into words. It hits me when I look at the contact sheets. There’s a certain irrational element that afterwards I can describe and try to analyze. I look at the sheets and suddenly I see, amid all the crap, something that sticks out and works – and works in a way that has a kind of hysterical tension in it. It’s funny, but also disturbing at the same time. It’s no longer the thing that was being photographed, it’s a scene, it’s almost a play.”

Kalvar shares how difficult it is to get great street photographs:

“I don’t have too many that work – after 40 years of photography, there were only 89 pictures in the show, but every once in a while the good things come together.”

How well could Kalvar identify a good street photograph when out on the streets? He shares he discovers it more through the editing process:

“I don’t set out looking for a certain kind of picture. It’s just that I’m kind of unconsciously drawn to that kind of thing, and I know when to recognize it in my contact sheets. Now, obviously, I’m doing the kind of things that might make it happen more.”

He describes a little more about “nailing” the shot:

“Let’s just say that it’s very satisfying. And nailing the picture is a two-step process: first photographing, then discovering if it really works on the contact sheet (or now on the computer screen).”

Takeaway point:

Realize that good street photographs come very infrequently. I think street photography is the most difficult genre of photography. This is because it is so unpredictable– and we have no control. We can’t control what our subjects look like, the light, the background– we can just be in the right spot and click at the right moment.

Even Richard Kalvar admits to only having 89 good photos after 40+ years of shooting in the streets. That averages to only around 2 good photos a year.

So realize everytime you go out to the streets– you’re not going to make a good photo. Work hard and hustle in the streets, but know that if you get 1-2 good photos a year, it is a good rate.

2. Walk around a lot

One of the most important traits of a street photographer is to have good legs– and to walk around a lot. Kalvar explains:

“I walk around a lot. That’s necessary. I try to go to places where interesting things might happen. And I’m always looking. At relations between people. I’m attracted to people doing things with each other. Mainly talking, as a matter of fact.”

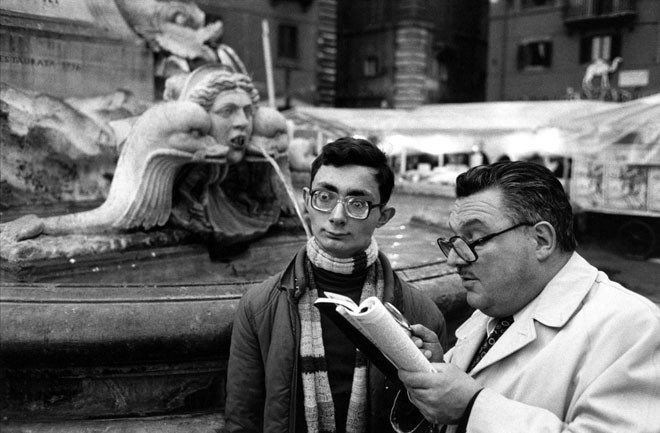

Kalvar is especially drawn to conversations in the streets:

“Whenever I see a conversation in the streets, I’m immediately attracted to it. I’m curious. I have your standard voyeuristic instincts, and conversation is great photographic raw material. Generally, nothing happens. It’s a conversation, so what, big deal! But every once in a while something does happen. By going after that kind of situation I increase my chances of being there when that thing happens that’s going to make the picture.”

Takeaway point:

The more you go out and shoot, the more likely you are to make a good photo. So increase your luck by walking around a lot. Be curious. Like Kalvar, be drawn to people, situations, and conversations. Realize that most of the time nothing will happen, but the more persistent you are– the more you will strike gold.

3. Let yourself go

How do you loosen up and see great “decisive moments” when you’re out on the streets? Kalvar lets his mind go– which helps moments come to him:

“It’s hard to know how much the situation is responsible for the picture and how much your availability is. In French, there’s a word,”disponible”, meaning, you’re letting yourself go, you’re available for things to happen. It’s a mental and emotional opening. In other words, you’re ready.“

Kalvar expands on the importance of being open and sensitive to photographic moments:

“Sometimes something obvious happens and you happen to have a camera and you take the picture, but sometimes it’s because you’re ready, you’re sensitive to things, and you’re not thinking about other things – you’re concentrated and you’re more open to things happening. I couldn’t tell you the exact percentage, but both ways of functioning come into play.”

Takeaway point:

I feel that to truly capture great street photographs is to be perceptive. To notice interesting things that happen in the world. It doesn’t matter what camera you have– you need to have observant eyes to see the world in a unique way.

So when you’re shooting in the streets– loosen up and let your mind go. Fall into the “flow” of things. Don’t feel so tense when you’re on the streets. Smile, chat to people, have a nice coffee, possibly listen to music– anything that helps you relax.

Once you relax on the streets, you can let the moments come to you (rather than needing to feel you always have to hunt for them).

4. It works, or it doesn’t work

In street photography, one of the most important things is to be brutal when it comes to editing. That means, being very selective with your best shots.

Kalvar stresses the importance of results in photography: it either works or it doesn’t work:

“What counts is the result. It works or it doesn’t work. You may think after you’ve taken a picture that you may have something. And then you find out that you don’t have anything, that you almost had something but that in fact, you pressed the button at the wrong time. That you took a lot of pictures, but you were on auto-pilot – that instead of waiting, you shot buckshot at it, so you missed the one that might really work.”

Kalvar also shares that you can “re-discover” great photos through his contact sheets:

“But every once in a while, I look at my contact sheets and I discover something I hadn’t even seen. That’s possible, too.”

Takeaway point:

Be absolutely brutal when you’re selecting your best images. Once again, Kalvar says he only gets 1-2 good photos a year. So perhaps when you’re editing your shots ask yourself: Is this photo going to be my best 1 or 2 photos in a year?

It is difficult to “kill your babies” photos that you feel emotionally connected to which may have an interesting backstory. But realize at the end of the day, your photo either works or it doesn’t work.

One of the best ways to edit your photos ruthlessly is to get feedback from another photographer who you trust. Tell them to be absolutely brutal– and help you only choose your best images (and which images to kill). It is painful, but necessary.

5. Take lousy photos

Don’t always expect to take great photos when you’re out on the streets. You have to take a lot of lousy photos to get the few good ones. Kalvar explains:

“Yeah, I take a lot of lousy pictures, and sometimes it turns out that one of the ones that I didn’t even think about was in fact pretty good.”

Kalvar also shares what he looks for when shooting in the streets:

“I don’t look for bushes or hands. I look for something that catches my interest, and I have no idea in advance what it might be. The next step is getting up the nerve to approach the subject without disrupting the scene or getting my face punched in. Then I might start taking a picture or two. In general, the result is pretty lousy, but every once in a while something unexpected happens (in reality, or in my brain) and I get excited. And then, even more rarely, I might succeed in making it into something special.”

Takeaway point:

Don’t be afraid of taking lousy photos. Rather, realize how many lousy photos you need to take in order to make a few great photos. It was Henri Cartier-Bresson who said: “Sometimes you need to milk the cow to get a little bit of cheese.”

So don’t be disappointed by all of your lousy photos. Rather, realize they are a necessary part of the equation to make great photos.

6. Take photos in a place you dream of

Kalvar is a big fan of traveling to re-inspire him in his work. He shares how he did his first project in Rome:

“Jean-Loup Sieff decided to do a series of books. He had Doisneau do one, and Martine Franck, who was also at Magnum, did one, and I was supposed to do the next one. The idea was that you get a little bit of money and go to some place you’ve always dreamt about working in, and take pictures. Then the Pope died, in ‘78. I got an assignment from Newsweek to take the same pictures everyone else was taking, and I’d never been to Rome. It was fantastic discovery! It was early in August, and Newsweek had an office near the Spanish Steps. I came in late afternoon, early evening, and the light – I was bowled over. So beautiful! It was so wonderful being in Rome. So I did the stuff that I had to do, and there’s the funeral, and the election of the new Pope. Between the two, there’s nothing.”

Kalvar shares how he took photos that interested him:

“I started wandering around, taking pictures for myself, in black and white. I was working for Newsweek in color, of course. It was great, being there, taking pictures. It was relatively easy to photograph. People weren’t hostile, and they were expressive! So I decided to do the Sieff book in Rome. Except that the book never happened, but I kept going back anyway.“

Takeaway point:

If you have always had a dream place to shoot street photography– go! You only have one life to live. There will always be concerns of time, family, and money. But if you never go, you will always regret it on your deathbed.

If you have a place in mind you want to shoot street photography, start planning for it immediately. Plan when you’d like to go, tell your friends and family, and start saving up money. You don’t want to miss out on the wonderful opportunity of traveling and photographing your dream location.

7. Be sneaky and aggressive

I personally don’t like being sneaky when shooting street photography– but this is the way that Kalvar works. He explains how he does this in order not to get noticed by his subjects:

“It’s more difficult now, but I**’m a fairly sneaky photographer**, so sometimes I can succeed in getting around it. I’m kind of shy and sneaky and aggressive at the same time. Sometimes I have the nerve, sometimes I don’t.“

Kalvar addresses the issue of people being suspicious– and how difficult it can be shooting in the streets:

“It’s true that as far as security is concerned, people are suspicious of everything now. America is in many ways a lawyer oriented society – everyone’s suing all the time – but for photography, America’s okay, and France is the most difficult place to work, for legal reasons. People here have a statutory right to their own image, and their privacy. You take a picture and they can sue you. Even if it doesn’t do them any harm! So that’s been a tremendous problem.”

Kalvar does admit it is getting a little better:

“It’s mostly the last 10 or 15 years, although it’s been getting a little better lately. For a while the courts were awarding damages to anyone who sued. It’s discouraging. Even now, you have magazines and newspapers that put bands on the eyes and pixelize faces and so on. It leads people to say, “Why are you taking my picture? You don’t have the right! You’re making money off my image!” That part’s really unpleasant and makes things difficult. It’s worse than it was before. It’s true in other countries too. Although often there are no problems, or they’re minor. There are more photographers around. Before, you might have been the first photographer who’d ever shown-up in a particular village. Now, there are people taking pictures with their telephones. It’s harder to work, but it’s not impossible.”

Takeaway point:

All the street photographers I know have some bit of fear, hesitations, and worries when it comes to shooting street photography. It is totally normal. There will be a lot of photos you miss taking because you weren’t bold enough.

Realize street photography is difficult for everybody– even the masters. But know that street photography is certainly not impossible. Just go out and shoot with a smile, and know why you are taking photos in the streets. You are photographing society, history, and trying to make a statement through your work. You are trying to express yourself, and experience the world through shooting in the streets. You’re not out there to hurt anybody– so don’t hesitate or feel guilty.

8. Be an amateur photographer

One interesting discussion Kalvar talks about quite frequently is splitting his personal work and his professional work. At the end of the day, he embraces the amateur in himself– and how it is often his non-professional work which is his best images:

“For my personal pictures, I’m not going to do anything different from what I’ve done in the past. I have 40 years work behind me, and it should be consistent. I like the feeling of film and the cameras that I use, so I don’t think I’ll change. But I’m an amateur photographer and a professional photographer. I’m a much more interesting amateur photographer than I am a professional photographer. The amateur just had the show here in Paris and is publishing the book and so on. The pro is the guy who’s trying to make a living and works for whomever will pay him. For that kind of work, I use a digital camera, nine times out of ten. There are great advantages to it – you can process cheaply and quickly, the quality very good. I’ve tried working with the Leica M8, but it wasn’t very successful. It’s not quite ready for prime time.”

Kalvar also discusses a bit talking digital versus film:

“Since I go back and forth, there are things I miss from digital when I’m working with a film camera. You don’t have to change the film roll when things are getting exciting. You can’t see the picture with a film camera – I wish I could do that a little bit, because I’ve gotten used to it. Sometimes it’s a question of habit. I use a Leica, and when I take a picture, I immediately advance the film. But sometimes now, I forget I have to do it myself, and I’ve missed a few pictures that way.”

In a blog post: “Schizophrenia” Kalvar discusses this dichotomy between professional and amateur work more. He starts off the importance of making a living as a professional photographer:

“A number of years ago I made the very regrettable error of allowing myself to be born into a family that didn’t have much money, so when I started photographing in a serious way, I had to find a means of making a living. At the time it didn’t seem to me that I could do that through my personal photographs, so I began to seek professional work taking pictures. I suppose that to support my habit I could have driven a taxi, or become a customs inspector like Henri Rousseau or Nathaniel Hawthorne, but using the camera seemed like the path of least resistance.”

However he did see some similarities between his professional and amateur work. They both were observational and candid:

“I started to get some work with newspapers and magazines, and then with commercial clients. The magazine work was often similar to my personal photography in that the photos were un-posed, and based on observation.”

But Kalvar shared the frustrations of doing professional work– having less control:

“There were important differences. The journalistic pictures were less free. They tended to be more descriptive, straight-forward and first-degree. And I couldn’t come back from a day’s shooting and say, “Too bad, I didn’t see anything that inspired me so I didn’t take any pictures”; as a professional, I had to produce and to meet a deadline, so the bar of acceptable quality was necessarily lower. I also did posed stuff, portraits and the like. Just between the two thousand of us, I enjoyed and continue to enjoy this kind of work: as a source of revenue of course, but also because it’s interesting to see and try different things, and to solve different problems. I like to say, in my immodest moments, that I’m a pretty good professional photographer, but a more interesting amateur one.”

He talks more about the drawbacks between working both professionally and doing personal work:

“Naturally there are drawbacks and dangers in serving two masters (oneself and someone else). A good friend of mine had another friend who was a sculptor, who also had trouble earning a living with his art. He took a design job at a factory that manufactured store window dummies, but was quickly let go when he couldn’t help making the legs too long, or the head too twisted. In my case the danger is more in the other direction. The client explicitly or implicitly defines the parameters. If I’m working for a press organ and I feel that the most interesting thing I’m seeing that day is my feet, I can be sure that my employer will be unhappy with the results. If I’m working for a large company organizing, say, an international get-together, I have no doubt that unflattering pictures of the participants will be frowned upon. To what extent will that lead to self-censorship, even of the photos that I take for my own pleasure while working for the client?”

But you can still balance professional and personal work. He brings up Elliott Erwitt for example, also in Magnum:

“How you present the various things you do can also be problematic. Someone I’ve always admired for his ability to walk and chew gum at the same time is my colleague Elliott Erwitt. He’s an excellent portraitist, a fantastic advertising photographer, an intelligent and sensitive photojournalist, and a superb observer of the human comedy. But far, far better than all that are his brilliantly witty found photographs, some of the finest ever taken. But Elliott has a tendency to put them all in the same bag, to publish them together. To my mind the mixture of genres, the juxtaposition of the great and the merely very good diminish the power of the best pictures. I wish he didn’t do that.”

Takeaway point:

I know a lot of people with full-time jobs who dream of being a professional photographer. Whenever somebody asks me how to become a professional photographer– I try to be encouraging and motivating, but honestly– I think it is better to separate the both.

“Serving two masters” can be difficult. To split one’s personal work and professional work can be exhausting and discouraging. I think it is wonderful how many people have day jobs to pay the bills, and can just do street photography completely on their own terms on the side.

I am personally lucky that I don’t do any commercial work. I make my living through teaching workshops. But even I have a hard time to find time to shoot– because I am quite busy blogging and running administrative things for travel, workshops, emails, finances, etc.

So regardless of what your job is, embrace the amateur inside you. You don’t need to be a professional to make great photos. Shoot what you love. Shoot what fascinates you.

9. Play with reality

Even though Richard Kalvar is part of Magnum, his work isn’t documentary. He rather likes to pay with mystery and reality in his photos:

“What’s always interested me in photography is the way you can play with reality. Photography is based on reality, it looks like reality, but it’s not reality. That’s true of anyone’s pictures. It’s a picture of something, but it’s not the thing itself. It’s different from the reality – it doesn’t move in space, it has no sound, but it reminds you of reality – so much so that you believe it’s reality.”

Kalvar shares the importance of creating abstraction to make more mystery in photos:

“In order for the mystery to work, you need abstraction from reality. Black and white is an additional abstraction, in addition to selective framing, to the freezing of the moment that in reality is a part of an infinite number of other moments (you have one moment and it never moves again; you can keep looking at the picture forever). The black and white is one more step away from reality. Color, for me, is realer, but less interesting.”

Kalvar also looks for creating little dramas in his photos:

“I’m trying to create little dramas that lead people to think, to feel, to dream, to fantasize, to smile… It’s more than just catching beautiful moments; I want to fascinate, to hypnotize, to move my viewers. Making greater statements about the world is not my thing. I think there’s a coherence in the work that comes not from an overriding philosophy but from a consistent way of looking and feeling.”

Takeaway point:

One of the things I love most about Kalvar’s work is how mysterious and strange it is. His work isn’t about telling the full story– it is about suggesting them.

Kalvar works in black and white to create more of a sense of mystery in his shots. You don’t always have to work in black and white to create this sense of drama– but it often helps create more abstraction.

If you want to create more more interesting photos, create more mystery. Don’t photograph everything in the frame. Decide what to include, and what to exclude. Blend your subject to the background. Get close, and build abstraction into your scene. Make the viewer think hard when looking at your images, and don’t give away the full story.

10. Keep things out of the frame

One mistake I see a lot of beginner street photographers make is to try to include everything in the frame. But to make a good frame is to be selective what to keep out of the frame. Kalvar explains:

“The framing is very important – you have to keep out things that distract from the little drama that’s in the picture. I’d like my pictures to exist almost in a dream state and have people react to them almost as if they’re coming in and out of daydreams, you know?”

Takeaway point:

Similar to the previous point, don’t tell the whole story by showing too much. Show less, and you will make a more interesting frame.

11. Stay genuine

We all want to be more recognized for our photography. But how do we balance pleasing our audience by creating original work– versus creating original work that is genuine to us? Kalvar shares the importance of being genuine in your photography:

“But it’s what I like to do, it’s natural for me. I’m not going to change now.” It’s true that if someone were to start doing what I do, or what Friedlander’s done, there’s less interest, unless it comes out of a genuine feeling, rather than a desire to imitate what’s already been done. If it comes out of something real, it’s not going to be the same as what other people did. When people find out I shoot black and white, they say, oh, just like Doisneau. Well, first of all, I do unposed pictures, and anyway I’m not Doisneau. What I do is different.”

Kalvar shares the importance of creating personal images:

“I think that other people coming along can use traditional form and do something creative and interesting and different from what other photographers do. If they do something that uses a traditional form and is not creative and interesting and different, and it’s not really personal, then I can understand the criticism of it.”

Kalvar also shares the importance of creating good photography, over creating unique work:

“Searching for novelty, in itself, is not very interesting. And a lot of stuff that’s shown now is crap. A lot of it isn’t. It’s not because it’s different that it becomes good. And it’s not because things are done in a more traditional way that they’re necessarily bad. You still want something that’s personal and creative, and to me, that’s the key, whatever form it takes.”

What is a timeless way to captivate your audience? Tell stories through your images:

“Think about movies or novels. It’s the same as it was 20 or 50 years ago. There are stories. People are interested in stories. In novels, people are interested in the story and how it’s told. The form evolves, but it’s possible to continue in a preexisting form and still do creative and interesting things.”

Takeaway point:

Don’t worry so much about creating unique work. Focus on making great and personal work. Be genuine in your photography.

You might copy the technique or approach of other photographers. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Just make sure you do it in your own unique way.

Remix the work that you have already seen before, and see how you can add your own personal spin.

12. Shoot from the heart, guts, and brain

In an interview, Blake Andrews asks Kalvar about his thoughts on street photography:

Blake: “I’m glad you mentioned Magnum because that was my next question. What do they think of street photography? I know there’s a range of personalities there. But some of them don’t get it? By street I mean amateur unplanned candids.”

Kalvar: “As you say, there’s quite a range. I get the feeling inside of Magnum and outside (especially outside) that a lot of people think it’s an old-fashioned approach: not taking unposed pictures, but having my particular sensibility. I think that I do what I feel like doing, which may not follow contemporary fashions but which comes spontaneously from the heart, the guts and the brain. To me, that’s what counts.“

Takeaway point:

I read a lot of arguments on the internet on the definition of street photography. The debate on posed versus unposed. The debate on taking photos on the streets versus indoors. The debate on asking for permission versus shooting without permission.

The old-school approach is to shoot street photography candidly. But as Kalvar says, follow your own sensibilities in street photography. Make your street photography personal. Don’t feel obliged to follow what others are doing.

Don’t follow the contemporary fashions in street photography. Let your work come “…spontaneously from the heart, the guts and the brain.” That is what truly counts.

13. Investigate conversations

What does Kalvar look for when he’s shooting on the streets? One of the tips he gives is to investigate conversations on the streets. He explains why:

“[Conversations are] good raw material for me, because they involve the interaction between people (or the lack of it), and that’s what I like to play with. I like hands and bushes; it’s just that I don’t go out looking for them. But they often hit me over the head.”

Takeaway point:

One of the best traits of a street photographer is to be curious. And slightly nosy.

So if you don’t know what to shoot on the streets, look for people in public having conversations with each other. This often leads to interesting hand gestures, facial expressions, and random happenings. Stick around them, and wait for any “decisive moments” that happen. And in that moment, shoot.

14. Don’t explain photos

Much of Richard Kalvar’s images have a great deal of mystery. When I look at his images as a viewer, I am quite curious of the back-story.

However Kalvar doesn’t like explaining the back-story of his photos, because he feels it kills the mystery of the shot. He explains in the interview with Blake Andrews:

Blake: “Can I ask about one specific photo, the woman eating a popsicle near the foot? That photo was sort of the entrée into your work for me. After I saw it I got very excited and looked up all your work. This was maybe 10 years ago. What was going on there?”

Kalvar: “First let me address the question “What was going on there?” in general. I try to avoid answering, because when I do, people generally stop looking and turn the page. If you kill the magic and the mystery, what’s left but humdrum reality? But just between you and me and the millions of people who read your blog, there was a woman eating a popsicle, a guy playing the guitar, and a another one taking a sunbath on the roof of his beat-up station wagon. He was kind of beat up, too.”

Kalvar continues by explaining how he likes to keep his images open-ended, for the viewers to come up with their own interpretations:

“It’s tempting to satisfy people’s curiosity as to what was “really going on” in a scene, but it always leaves a bad taste in my mouth. If there’s a mystery, the viewer should try to unravel it for him- or herself, subjectively, through intelligence, imagination and association. I want people to keep looking, not just move on to the next thing.“

Kalvar ends by sharing another tip: a great way to make more engaging photos is to tell lies:

“That’s part of the magic of photography. Look at a picture and you have no idea what was going on. The only thing you can know is what’s visually depicted, and we all know photographers lie. That’s where the fun comes in. To be able to tell a lie with “reality” is a very tough trick.”

Takeaway point:

One thing that annoys me is when I see elaborate back-stories being explained in photographs in captions on Facebook or Flickr. Although I do love hearing the backstory, I feel it kills some of the magic in a photograph. I like the sense of mystery, and being able to come up with my own little story in my head.

I generally recommend most photographers to title or caption their photos simply: location and date. That provides enough context to the scene, but also leaves the image open-ended enough.

Know that the most interesting photos are the ones that tend to have mystery. Know that in street photography, you don’t need to feel obligated to tell “truths.” All photos are a fabrication of the way we see reality. So in a sense, they are all “lies.” But make interesting lies with your images– that create a sense of wonderment, curiosity, and excitement in your viewers.

15. On the definition of “street photography”

Kalvar expands on how he personally feels when people describe his work as “street photography”:

“I’m not crazy about the term “street photography” to describe what I do, because it’s not necessarily done on the street. The pictures can be taken on a farm, at the zoo, in an office, and so on. Let’s say we consider the general category of “unposed pictures of people” (or sometimes animals or even inanimate objects when they happen to be possessed by human souls), and then the subcategory “with nothing particularly important going on.””

Kalvar says if he could define what he likes to do, it is to play with reality and drama in everyday life:

“If we further narrow it down to the “play” sub-subcategory, we get into the domain I’ve worked in for forty years. That’s what I like to do: play with ordinary reality, using unposed actors who are oblivious to the dramas I’ve placed them in.”

How does Kalvar define “street photography”? He shares that he doesn’t think street photography necessarily has to be done on the streets:

“The kind of photography I do for pleasure is generally called “Street Photography”, but no one who actually does it limits himself or herself to the street. We take pictures wherever we find them, and whether it’s on the street or on a farm or at a wedding makes no difference.”

However an important distinction Kalvar gives is the difference between candid and posed images:

“The key distinction is not between “street and “non-street”, but between “found” and “set up”.”

The last important difference Kalvar brings up is when photography is “acceptable” or not. For example, in the streets versus private events:

“There’s another useful distinction to be made, between situations where it’s acceptable to take pictures and those where it’s not. Walking around sticking your camera in people’s faces when they don’t know what you’re up to is risky business; photographing at a wedding is generally not (although I photographed at a wedding in Naples in 2011 and got an awful lot of funny looks…).”

Takeaway point:

Richard Kalvar isn’t a stickler when it comes to defining street photography. For himself, he likes to take unposed photos in public areas (not necessarily the streets). He also likes to create a sense of drama in his images.

However what I love about him is that he allows other street photographers the flexibility to shoot however they would like to. He could care less where and how photographers shoot. But he does bring up the important distinction between candid vs posed shots, and photos on the streets versus “acceptable” situations.

At the end of the day, shoot whatever interests you. Don’t care if it is called “street photography” or not. Create your own personal definition for street photography and disregard what others say.

16. Travel a lot

What advice does Kalvar have for photographers starting off? He stresses the importance of traveling:

“Travel a lot; try to go to places where interesting things might happen. In the late 60s, after I worked for Jerome Ducrot, I saved up a little money and came to Europe to hitchhike with the camera he gave me as a present, and a couple of lenses. I wasn’t there to photograph –[traveling round Europe] was one of the things that people did back then. I started taking a few pictures. I wouldn’t say it was a project, but by the time I went back, after 10 months, I was a photographer. That’s the thing that changed my life the most, that trip.“

Takeaway point:

You don’t need to travel to become a great street photographer. But if you are starting off in photography– traveling is a great way to get your feet wet. It is a great opportunity to travel, meet new people, see new sights, and feed your visual palette.

So rather than saving up money to buy that new camera or lens, invest the funds for experiences. Rather than using that $1000 for gear, use it for a round-trip ticket to somewhere in the world. Use that money to travel and see the world. That will be the best experience money can buy, and which will truly help your photography.

17. On “Decisive Moments”

In street photography, we talk a lot about “decisive moments.” What does Kalvar think about “the decisive moment?” He dispels some notions, and shares how “the decisive moment” is a very personal and subjective thing. What may be “decisive” to you, may not be “decisive” to me. Kalvar shares:

“At the last Magnum annual meeting in Arles, at the end of June, we were looking at portfolios of potential nominees. During the projection of the portfolio of a photographer who had a lot of pictures of meaningless moments, I remarked that I was tired of seeing pictures where there would be no apparent difference if the picture had been taken a second before or a second after. One of my colleagues said with a derisive and dismissive snort, “Oh, he still believes in the Decisive Moment!”.”

However Kalvar explains the irony– that all photographers are looking for some kind of “decisive moments”:

“I looked around the room (with my mind’s eye, that is) and I saw that almost all of us, the ones that photograph humans and animals, at least, are looking for the decisive moment. Anyone can photograph indecisive moments; of what interest could it possibly be to look at the photographs of 7 billion people photographing just anything? What about the photographers who still believe in the interestingly or well-composed picture, the one that really grabs you? How old-fashioned!”

Kalvar paints two conclusions regarding the decisive moment. The first is how subjective a “decisive moment” can be:

1.”The first is that the moment that Henri Cartier-Bresson thought was decisive is not the same decisive moment for everyone. Henri made rules about what should be done, but he was in fact describing what HE did. Your decisive moment is not the same as mine, but most of us are looking for a moment that is necessary for what we’re trying to do. Unnecessary moments quickly become easy, common, and boring.””

The second is how it it is important to break the rules:

2.”The second thing is that it’s sometimes good to break the rules. But if the rules are pretty good to begin with, that iconoclasm only works the first couple of times. Afterwards it’s just repetitive and uninteresting, the new and less good normal. And as I said, easy.”

Kalvar expands on the idea of having rules:

“By the way, HCB was totally opposed to cropping pictures. But he cropped [the famous photograph of the man jumping over the puddle].”

He wraps up his thoughts on the “decisive moment”:

“We each have our own criteria for the decisive moment. But in any case a second earlier or a second later and the pictures would be about as interesting as much of the stuff you currently see on walls.“

Takeaway point:

Sometimes I feel frustrated when I miss “the decisive moment” on the streets. For example, I was shooting on the streets of NYC yesterday, and missed a “decisive moment” of a man in a suit puffing a cigar. It made me angry and frustrated that I was a bit too slow. But I kept my chin up, and low and behold– 10 minutes later I see another guy in a suit smoking a cigar, and this time I got the photograph!

Know there are billions of “decisive moments” happening every second, every day, everywhere around the world. If you miss one “decisive moment” it doesn’t mean you won’t find a more interesting “decisive moment” somewhere else.

“The decisive moment” is also a very subjective thing. What you define as “the decisive moment” isn’t the same as what another person might find as “the decisive moment.”

But at the same time, don’t just try to seek “decisive moments” for the sake of them. As Kalvar recounts, many photographers are bored of just seeing cliche photos of people jumping over puddles. Rather, think about the emotion, meaning, and depth of your images. Don’t just rely on capturing some weird or wacky moments.

18. On “rules”

In photography, there are no rules. Only guidelines. However funny enough for Kalvar, following “the rules” actually helped him in his photography.

He starts off by starting with a quote from W. Eugene Smith in which he says: “I didn’t write the rules, why should I follow them?”. Kalvar shares his fascination with the quote– and how he started off by following “the rules”:

“That’s a great quote (and a fascinating interview). When I first began in photography I ingurgitated a number of rules for the worst possible reasons, which I then regurgitated in my photos. Don’t crop, shoot in black and white, don’t set up pictures… all part of the photographic zeitgeist, the Cartier-Bressonian canon.”

He also shares how photographers can get suckered into buying certain cameras, because they “should”:

“And then I ran into a friend of mine, another struggling young photographer named Nick Lawrence who was a little ahead of me at the time. He used a Leica, and when I asked him why, he said that Leica was the best, and owning one he didn’t have to think about equipment any more. That seemed to make sense to me, so I saved up and bought myself an M4. What a dumb reason to buy a camera!“

However sometimes having these “rules” can actually end up helping you:

“So there I was, equipped with the standard rules and the standard camera. Well you know, sometimes it turns out that the things that you do for the wrong reasons turn out to be the right things to do anyway. In retrospect, I’m really glad that I decided not to crop, because that developed my compositional discipline and my ability to organize a picture instinctively, in the viewfinder. It also obliged me to work very close up to my subjects in order to fill my 35mm lens frame. I had to be a toreador, not a sniper. Also, I had the feeling of doing something difficult, getting the picture right in the first place; anyone could crop a picture and find something interesting, but doing it in the camera was special. These things were essential to my photographic development.”

Kalvar also shares how working in black and white (the tradition of street photography) helped him find his own personal vision:

“As I evolved I quickly understood that what fascinated me were the differences between the frozen, isolated, silent photograph and the reality it purported to represent, and at the same time the obvious resemblances between the two. I could play with the notion that people thought that a picture was reality when of course it wasn’t. Photographing in black and white created a further level of abstraction. The black and white pushed the link but didn’t break it, and made the overall impression more dreamlike. So that rule served me well.”

The “rule” that Henri Cartier-Bresson also made in photography was to not pose photos. Even though this was restrictive, it ended up helping Kalvar in the long run:

“Since I was playing at the intersection of appearance and reality, the credibility of the reality leg was essential. Setting pictures up (or today, modifying them in Photoshop) would destroy the relationship between the two. It would cheapen my photography. By posing pictures, people like Doisneau lessened the value of their work. You never know whether they’ve set something up (easy), or found it and tamed it (hard!). Some photographers like Elliot Erwitt have managed to work successfully on the edge, but that wouldn’t be right for me.”

Lastly, the “rule” in street photography was to shoot with a Leica. However in the end, it ended up working for him too:

“Photographing with my discrete little Leica allowed me to remain unobtrusive despite being very close to my subjects, without which nothing would have been possible.”

The last quote that sums up Kalvar’s thoughts on rules is:

“I didn’t write the rules, but following them set me free.”

Kalvar also brings up some interesting caveats regarding his personal rules in his photography:

- Sometimes people set pictures up FOR you, but that’s part of reality, too.

- For a while, for some strange reason, I believed that you shouldn’t have people looking directly into the camera – rule 427B. That one fell by the wayside pretty quickly, as I realized that some of the best pictures were the ones where people were looking directly at you, creating a link between you and the rest of the scene. It’s okay if people look at you, as long as you don’t tell them to do it (rule 223F, paragraph 17).

Takeaway point:

Kalvar started his photography by following the “rules” of Henri Cartier-Bresson, which included shooting with a Leica, not cropping, shooting in black and white, and not posing photos.

Even though the “rules” were very restrictive– Kalvar says that having these restrictions eventually “set him free” in his photography, and helped him tremendously.

However not all of us are Henri Cartier-Bresson or Richard Kalvar. Following these “rules” won’t necessarily help all of us.

On the other hand, if you are a photographer just starting off– following some “rules” (or I like to call “guidelines”) help us in our photography. I think by creating restrictions in our work, this helps us be more creative. So it is good to start off by following the rules and guidelines of others in photography– but as time goes on, create your own set of rules.

My personal rules in street photography are below:

- Don’t mix black and white and color in a series

- Don’t crop

- Don’t upload images until I let them marinate and sit for at least a month (preferably a year)

- Focus on projects, not single images

- Don’t mix digital and film in a project (sometimes I break this rule)

- Don’t share any images online until I have gotten critique in real-life

Don’t feel obliged to follow my “rules” in street photography– but take the pieces you like, discard the rest, and modify and remix them.

Conclusion

Richard Kalvar is a great source of inspiration and knowledge. I think my biggest take-aways from him is the importance of creating a sense of mystery in photographs, and not telling the full story. Let the viewer do the work of interpreting the photograph for themselves.

Also don’t worry too much about the definitions of “street photography” photograph what interests you, and how you like to photograph.

Lastly, make your photography personal. Shoot for yourself, be true to your own voice, and explore the world with your camera.

Videos

Earthlings by Richard Kalvar/ Magnum Photos

Bookflip: Earthlings by Richard Kalvar

Richard Kalvar: In Studio

Book

Richard Kalvar: Earthlings

The book you must get from Richard Kavlar is: “Earthlings” — a monograph of his finest street photographs.

Related photographers

If you like the work of Richard Kalvar, here are some other street photographers whose work I would recommend:

- Henri Cartier-Bresson (the master of “the decisive moment”)

- Elliott Erwitt (they both share a sense of humor and quirkiness in the streets)

- Richard Bram (great simply, quirky, and classic b/w street photography)

- Blake Andrews(A great black and white contemporary street photographer, prolific, and extremely observant)

Links

- Richard Kalvar Magnum Portfolio

- Richard Kalvar Interview Part 2 (2point8)

- Richard Kalvar Interview Part 2 (2point8)

- Richard Kalvar: In-Public Portfolio

- Richard Kalvar Magnum Blog

- Q&A with Richard Kalvar (Blake Andrews Blog)