Download this article:

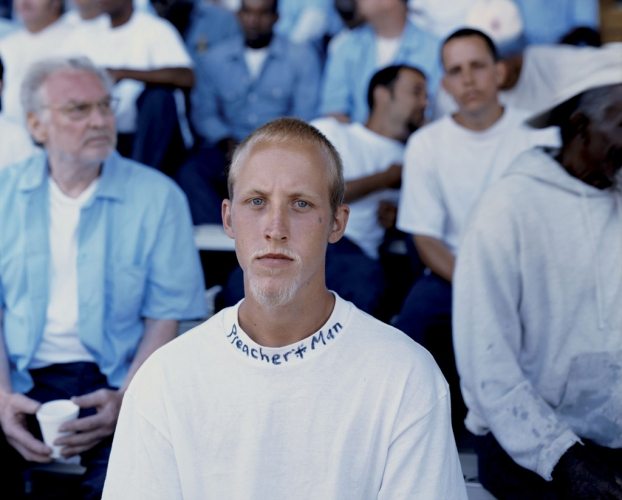

All photos in this article are copyrighted by Alec Soth / Magnum Photos.

Alec Soth is a photographer whose work I strongly admire. He is a member of Magnum, although he is not the typical “Magnum” photographer. He is generally identified in the “fine art”/documentary crowd– and certainly isn’t considered a “street photographer.” However his philosophies in photography and the way he interacts and photographs his subjects in an empathetic way really helps me connect with him (in street photography).

In this article I want to share some things how Alec Soth has inspired me– both in terms of a human being and as a street photographer:

1. On Titles

Alec Soth is a project-based photographer, meaning that he doesn’t simply go out and shoot single images to upload to Flickr or Facebook. He generally goes out with concepts in his mind in terms of what to photograph. And of course he modifies his projects as he shoots.

One of the things I love most about Alec Soth is how poetic he is– both in terms of his writing, his photography, and the way he talks about his work.

One of my most prized books from Alec Soth is “From Here to there: Alec Soth’s America.” In the book, he has a compilation of images from his most renowned projects–while inserting commentary on photography which is from his old Archived Blog.

In one of the sections in the book (also can be seen on his blog) is about the importance of titles for him:

“Men might think about sex every seven seconds, but I think about project titles. There is no greater pleasure than lying on the couch, closing my eyes, and daydreaming about the perfect title.

Alec Soth also teaches photography, and one of the things he advises his students is to at least have a “working title” when it comes to working on a project:

“Titles are important. When I review student work, one of the first questions I ask is “what is the title?” More often than not I’m met with no answer. This is remarkable. I’d have a hard time getting started on anything without having some sort of working title.”

Alec Soth continues by sharing how viewers perceive a project differently based on the title:

“Titles are important. They affect the way people read the work. Take Nan Goldin’s “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.” The title is so urgent and unexpected. Imagine if the book was just called “Downtown.” I doubt we’d think of the book in the same way.”

Soth also shares the dangers of having “bad” or boring titles:

“It’s a shame when a great book gets a bad name. One of my favorites of the last few years was Jem Southam’s “Landscape Stories.” The title is generic and lifeless– just the opposite of his sensual and complicated pictures. (I much prefer the title of Southam’s latest book, “The Painter’s Pool”).”

But at the end of the day, Soth would still prefer a more interesting title (than a lifeless one):

“Sometimes photographers get corny. David Heath’s “Dialogue With Solitude” is an example. But I’d rather have a corny title than a boring one. I’m a sucker for DeCarava’s “Sweet Flypaper of Life.”

Soth also suggests that sometimes photographers don’t need to have the fanciest titles though to best describe their work:

“I’m not suggesting that a title needs to be wordy and poetic. One of the most memorable titles is Winogrand’s “Women are Beautiful.” It’s so dumb that it is smart. It sticks. This brings to mind Malcom Gladwell’s book: “The Tipping Point.” He offers up some good advice for those of us daydreaming about titles:

‘The hard part of communication is often figuring out how to make sure a message doesn’t go in one ear and out the other. Stickiness means that a message makes an impact. You can’t get it out of your heard. It sticks in your memory…’

Takeaway point:

I think generally in the realm of street photography, most of us are focused on single-images rather than working on projects. When I started street photography– I was this way. I would go out everyday to “hunt” for the perfect “decisive moment.” When I would get a shot that I liked, I would immediately rush home, post-process it, and upload it to social media, waiting to get lots of favorites, likes, and comments.

However over time, I have started working on projects that are much more meaningful to me. I am still not the best at titling my work as they tend to be generic like: “Suits”, “Colors”, “Downtown LA in Color”. I think I need to make more interesting and emotionally stirring titles like: “Dark Skies Over Tokyo” or “The City of Angels.”

Regardless, I think that we should try to title projects we are working on. By titling a project, it gives us better clarity and direction in our work. When making a title, it can either be descriptive in terms of a place or a location. Or it can be more open-ended in terms of a project that is more poetic.

Alec Soth has some lovely titles in his work– which are short, poetic, and not overly cheesy:

- Broken Manual

- The Last Days of W

- Paris / Minnesota

- Dog Days, Botoga

- NIAGARA

- Sleeping by the Mississippi

- Looking for Love

At the end of the day, coming up with a title is more like poetry than mathematics. Everyone has their own tastes when it comes to titles. But at the end of the day, I think titling our work is better than not titling our work (even though it may be cheesy).

2. On overcoming the fear of shooting strangers

One of the biggest roadblocks many street photographers face (myself included) is getting over the fear of photographing strangers. It can be very nerve-wracking– to step outside of your comfort zone and interact with a complete stranger.

Many photos by Alec Soth include portraits. Portraits of people on the streets, in their homes, or even naked in motel rooms (like in his work in NIAGARA).

When I first saw Soth’s images– I assumed that he was the type of person who was completely fearless around strangers. But I found out that wasn’t necessarily the case. Soth shares how he overcame his fear of photographing people:

“I started out with kids because that was less threatening. I eventually worked my way up to every type of person. At first, I trembled every time I took a picture. My confidence grew, but it took a long time. I still get nervous today. When I shoot assignments I’m notorious amongst my assistants for sweating. It’s very embarrassing. I did a picture for the The New Yorker recently and I was drenched in sweat by the end and it was the middle of winter.”

Takeaway point:

Even the most experienced photographers in the world (like Alec Soth) still have fear when photographing strangers. To build your confidence in photography also takes a long time– and is a constant uphill battle.

I would say personally when I first started to shoot street photography, I was petrified. Even when making eye contact with a stranger would send cold chills going up my spine– and cause me to sweat profusely.

However over time, as I practiced more and started to talk to more strangers– this fear started to slowly go away. And now for the most part I don’t have that much fear when shooting in the streets. But there are still instances where I hesitate to take a photograph because I’m worried about how people may respond.

So know that overcoming your fear of shooting street photography is a slow process– but slowly and surely, you will build your confidence over time.

3. On photo books

Alec Soth is a huge advocate of photography books. In-fact, he started a small enterprise he calls “Little Brown Mushroom” where he collaborates with other photographers and artists and publishes limited-run books and magazines.

In an interview, Soth shares some of his thoughts on photography books:

Miki Johnson: What do you think photo books will look like in 10 years?

Soth: While most print media is dying, the photo book is going through a renaissance. I can only hope the vibrancy and appreciation of this medium will increase. If we’re lucky, maybe by 2020 The New York Times Book Review will give photobooks the same attention they give, say, graphic novels.

Nowadays digital books (on iPads, etc) are becoming more popular. Soth shares his thoughts on digital vs physical books as well:

Johnson: Will they be digital or physical?

Soth: They’ll be physical in my house. But then I’m getting old.

Johnson: Open-source or proprietary?

Um, really old.

Johnson: Will they be read on a Kindle or an iPhone?

Soth: I suppose, whatever. But there will also be physical books. All I care about is physical books. When I’m not making them, I’m buying them. I have zero interest in making or buying a digital book. That said, I am truly excited about the potential of new media for photographers. I’m currently experimenting with online audio slide shows and the like. But I see this as a new medium, not a book. For me, a book is a physical object.

At the end of the day, Soth is only really interested in physical books– but he still sees the merit in digital avenues of presenting work. Soth also shares some of his thoughts on the democratization of making books through self-publishing:

“Part of the photobook renaissance has to do with the increased ease of DIY printing and distribution. Just as musicians no longer require professional studios to cut an album, photographers have the ability to make their own books. Lately I’ve been dipping my toes in these waters. One of the things I’ve learned is that the options are really vast. New technology will only offer more options. But I should be clear that this doesn’t make publishers obsolete. Gerhard Steidl has devoted his life to learning the craft of bookmaking. I’ll never compete with that.”

Soth also shares how nobody really knows what makes a great book. It is something you just work hard towards, and sometimes with enough effort and luck– magic happens:

“My aim is to try to make a great book. That’s what I want to do. And what does that mean? I have no idea what a great book is. What I do know is that it isn’t a formula. It’s like a great album, maybe the band has to spend three years in the studio doing it or maybe it’s live in one take over a weekend. Knowing it’s not a formula, I know that I have to keep shaking these up, so I do something fast, then do something that takes years, trying different things. Do the stuff where I work alone, do the stuff where I work collaboratively. Sometimes it will fall flat, but hopefully magic will strike at some point.“

When it comes to books versus exhibitions, Soth prefers books as well (due to the sense of control you have):

“I’m a project-based photographer; I think in narrative terms, the way a writer thinks of a book, or a filmmaker a film. The thing about a book is that you can control the entire shape of it, unlike an exhibition where the parameters always change; you might have three rooms in one and one room in the next.”

Takeaway point:

I have invested in many photo books the last few years, and they have been the most instrumental part of helping me learn more about photography. Even though I do love the democracy of digital books (on the iPad and such)– at the end of the day, nothing beats a physical book.

A physical book is beautiful because it exists. You can hold it in your hands. You can lend it to a friend. You can sit down and relax on your couch with a nice coffee or a glass of wine, and leisurely look through images. When it comes to looking at photos on a computer, it doesn’t have the same charm.

I am a huge fan of self-publishing, especially companies like Blurb and Magcloud. In the past there were so many gate-keepers which prevented photographers from publishing their work in book format, but now the only thing that is stopping us is our own imagination.

If you have never created a book, I highly recommend you to aim towards working on a book. And even though Blurb isn’t as good quality as a traditional publisher, it is still a beautiful manifestation of your work– in a form that exists in a physical form.

4. Can photos tell stories?

What I think makes a memorable photograph is an image that “tells a story.” An image that makes you imagine what is happening behind-the-scenes, and causes you to interact with it.

However Soth doesn’t buy this argument. He doesn’t believe that a single image can tell a story. And with this I agree– Soth says you need multiple images to tell a story. Stories need a beginning, a middle, and an end. A single image cannot show that. Soth shares some more thoughts on this problem:

“Richard Woodward pointed me to the brewing controversy surrounding this 9/11 picture by Thomas Hoepker of Magnum. The controversy was triggered by this Frank Rich editorial. I emailed Thomas to get his opinion. He said he is giving it time (wise) and will probably write something for Slate.

For me this just reveals, once again, the biggest problem with photography. Photographs aren’t good at telling stories. Stories require a beginning, middle and end. They require the progression of time. Photographs stop time. They are frozen. Mute. As viewers of the picture, we have no idea what those people on the waterfront are talking about.

However Soth does bring up the point that while photographs can’t tell stories– they are great at “suggesting” stories:

“So what are photographs good at? While they can’t tell stories, they are brilliant at suggesting stories. Photographs are successful in advertising because they help suggest that if we buy X we will have the perfect lifestyle. And photographs are successful as propaganda because they can function as proof for whatever agenda someone wants to suggest.

Soth concludes by sharing how a single photograph can’t provide enough context to show the real story behind an image. He refers to the controversial 9/11 picture by Thomas Hoepker:

“I have no idea what is going on in that picture. And I’m pretty suspicious of anyone using it as proof of anything. You can’t tell provide context in 1/500th of a second.“

Takeaway point:

Photography is a very powerful, but limited medium. I love the power of single images– how they can surprise, impress, and create a sense of wonderment. Steve McCurry and Elliott Erwitt have more or less built their career on single images– so I don’t think that shooting single images is a “bad” thing.

However what Soth reminds me is the importance of working on projects. While a single image can provide a nice “suggestion” of a story– a project with multiple images and a beginning, middle, and an end will have much more powerful and context.

5. On using an 8×10 camera

Alec Soth is not only famous for his projects, but the fact that he uses a large-format 8×10 camera to photograph his subjects. Many fine-art photographers have utilized 8×10 cameras in history– and Soth shares why he decided on using such a big and cumbersome camera in his work:

“For the record, I don’t always use this camera. But my two published books, Sleeping by the Mississippi and NIAGARA were indeed produced with an 8×10. At one point I looked at the photographers I loved and there happened to be an unusual number who use this format (Nicholas Nixon, Sally Mann, Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld, Roger Mertin, Joel Meyerowitz). Since it worked for all of these people I figured it was worth a try. And as it turns out there is something special about the format. Beyond the resolution and tonal purity of the negative, the 300mm lens renders the world in a really unique way. But what I really love is the viewing process. The image on the ground glass is just so beautiful. While the format is pretty impractical, I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to give up on the view.”

However Alec Soth doesn’t only shoot with an 8×10 camera, but he is often pigeon-holed by others as thinking that his camera defines his work. Alec Soth gave a talk in Detroit last year, and one of the points he brought up was quite interesting.

He talked about how he didn’t want to only shoot with an 8×10 for his projects. He shared how he has used different formats, like medium-format, and digital as well. He used the analogy of wanting to be like a movie director: to have the freedom to use different equipment for different movies.

Takeaway point:

I think different photographic projects work better with other types of equipment. For example, if you are shooting mostly landscapes– it might be better to have a camera with more detail and resolution. However when photographing on the street, generally having small, quick, and nimble cameras generally work better.

However it is important for us to not let our equipment define us and our photography. I cringe whenever I see some photographers self-describe themselves as “Leica photographers.” I think this is as silly as people to describe themselves as “Whole food shoppers” or “Fiji water drinkers.” We should let our photography define ourselves, not the tools we use.

I think we should also have the freedom to experiment with our equipment and not only feel we have to shoot in one format (film vs digital) or either black and white vs color. But I still think there needs to be some consistency with the format and equipment when working on a certain project. But when working on different projects, I recommend trying to use different equipment (if you feel the need to be).

For example, for my “Suits” and “Colors” project I am shooting it all exclusively on Kodak Portra 400 film with a 35mm focal length on my Leica MP. But for my black & white documentary work , I prefer to work in digital with a Ricoh GRD V (like in my Gallo boxing series).

6. On shooting everyday

One of the things I encourage most street photographers to do is to always carry your camera with you, and to shoot everyday.

However Alec Soth doesn’t agree. He doesn’t shoot everyday– and likens photography more to film-making:

“I don’t come close to shooting every day. For better or worse, I don’t carry a camera with me everywhere I go. I liken my process to that of filmmaking. First I conceive of the idea. Then I do pre-production and fundraising. Then shooting. Then editing. Then distribution (books and galleries). As with most filmmakers, the shooting takes just a fraction of my time.”

Takeaway point:

I think that at the end of the day, I think it is a good practice to try to carry your camera with you everywhere you go, and try to take photographs everyday. I think this is good advice especially for those of us who can’t find enough time to take photographs.

However Alec Soth is coming from a project-based approach, in which he uses his camera to put together books and bodies of work. In that case, carrying a camera with you everywhere you go may not really make sense– because you should only be photographing your project (and not get distracted by other things).

I think the main takeaway point is that depending on your goals in your photography– location and context matter. Meaning, if you are just a hobbyist trying to find enough time to take photos– take your camera with you everywhere you go and try to take as many shots as you can. But if you are working on a project, try not to be too distracted by photographing too many things– which may not have cohesion and consistency in your work.

7. Do the work

I think many of us have a “dream project” or some photographic concept we would like to pursue. We may have all of these plans, but none of those plans really matter until we actually do the work– and photograph.

Alec Soth is a pragmatist in the sense that he believes the same things. Rather than just thinking of projects, we just need to go out and do it.

Soth brings up the issue that many young photographers try too much to promote themselves and their work, without having a substantial body of work yet:

“Now I’m in the position where I see a lot of young photographers pushing their work, and I think that’s fine, but so often it’s wasted effort before the work is ready. Everyone’s running around trying to promote themselves, and you kinda have to put in those years of hard work to make something decent before you do that. Particularly that first project is the hardest thing. I always say the 20s are the hardest decade because you don’t have money and you don’t have a reputation. In relation to this kind of issue, I’m always wary that the advice is like “you need to put together this promo package that you send out to these 100 people.” No, you need to do the work, and worry about that later.“

Furthermore, sometimes we can let work and monetary constraints be excuses to prevent us from working on our photographic projects. Sometimes we are also unsure about our projects– in terms of what direction they will take us, or how they will end up. Soth once again comes to the rescue by sharing his experiences balancing working and pursuing his personal project (Sleeping by the Mississippi, his first published work):

“I went shooting every weekend, more or less. In the beginning, for example, coming out of school I didn’t know how to photograph other people. I was a super shy person so I was terrified, but I knew that I had to learn how to do that, so I just went out practicing, essentially. At that time, when I was working those jobs, it was really an unhappy time. My job was terrible, the first job. Then I’m going out and taking these pictures which I know are not a real project—it’s like, not great work, just practice. I shot black and white because I could print black and white at work. You figure out stuff like that—it’s maybe not ideally what you would be doing, but those limitations have benefits as well.

Takeaway point:

There are never perfect conditions for you to work on your project. We will always make excuses that we are too busy, our job prevents us from working on it, or that we don’t have the right equipment, or that we don’t have enough money. I have fallen to this trap many times before– but I found it to just be a mental barrier of my “inner-critic.” I made up excuses because I was nervous and insecure about myself.

Whenever I work on a project, I have a general concept and idea in mind. But the more I spend time thinking about it, trying to visualize it– the less productive I am. The best way is for me to just kick myself in the ass– and go out and work on the project. Just do the work.

8. On living in a certain location

In my photography, I always told myself that my work would be much more interesting if I lived in an exotic place like Tokyo, New York, or Paris. I always saw where I lived as boring and un-interesting.

However funny enough– the people I know who live in those places don’t feel any more inspired than I do. They find where they live to be boring– and they wish to live somewhere else as well. For example, my friend in Tokyo wants to move to New York. My friend in New York wants to move to Paris. My friend in Paris wants to move to Tokyo. The grass is always greener on the other side.

Alec Soth is one of the most famous and commercially successful photographers out there. However he still keeps Minneapolis his home base– rather than New York or LA. Soth shares this struggle of living in a more “interesting” place:

“I am a Minnesotan. Writers are allowed to live where they live. But there’s something about being an artist that historically meant you had to move to New York. It’s really stupid, if you think about it. Because the subject matter, presumably, exists out there. And all these photographers that I know in New York can’t photograph in New York, and they go other places to photograph. I am of this place. It drives me crazy, and I fantasize about living other places, but New York is not one of them. I am interested in regional art in that there are these little regional differences to things that are quite interesting.”

Takeaway point:

Alec Soth lives in Minneapolis, which isn’t the biggest city when it comes to photography or the fine art world. However Soth still makes do with where he is– and is still producing great art and work.

One of my favorite projects by Alec Soth is “Sleeping by the Mississippi” and that was done in Mississippi, which isn’t nearly as exotic as Tokyo or Paris. Another interesting project he has worked on was “Paris / Minnesota” where he photographed in both places and directly juxtaposed them (showed their similarities and dissimilarities).

Currently I live in Berkeley, which is a pretty interesting place. But I still wonder to myself, man– would my photography be more interesting if I lived in SF, or possibly New York? I still get the urge to live somewhere more “interesting” but I have discovered that even my neighborhood has been very interesting to photograph. Even though there aren’t as many people walking the streets of Berkeley, I find myself shooting more “urban landscapes.” I have just adapted to my environment, and I also find it interesting to photograph here, as cities such as New York and Paris have been photographed to death.

So regardless of how boring of an area you live in– use that to your benefit and cherish it. The more remote or boring the place you live in– the more interesting photography you will make out there, because not as many people would have photographed the area. You can make great photography wherever you live, don’t ever let the dream of moving to a bigger city fool you.

9. Keep things out of the frame

In street photography, I often see people trying to cram too much information and context into a shot. I think rather than trying to make our frames more complicated and add more things into the frame– we should try to simplify. We should try to remove things from the frame. Addition via subtraction. This is what Alec Soth shares:

“With Mississippi, in particular, I had no money. I could take a few pictures of something that really affected the photography in big ways. After that, with a bit more money to play around with, I could take multiple versions of the picture. That’s part of how I got better as a photographer.”

“I have this thing, the camera’s on a tripod, it’s like an easel “Ok, I can only take a couple, I gotta makes this great.” Then I tried to get everything in the frame, which, in fact, is not a good strategy for photography. Its pulling stuff out of the frame is usually what you want to do, to simplify it. But I didn’t know that. So that was one of the lessons learned.”

Takeaway point:

Know that by deciding what to leave out of the frame is more important than what to include in the frame. If you have ever seen a photograph with a fish-eye lens you will understand my point. Often having too much information and things in the frame will make the frame too overwhelming and complicated. there is simply too much stuff to look at.

So when you are taking shots in the street, think to yourself: what should I decide to include, and what to exclude in my frame? Less is more.

10. Have a “shot list”

Many professional photographers (especially wedding photographers I know) have a “shot list.” They know what kind of shots they need to take before going into a client shoot or shooting a wedding. Of course, not all the shots go according to plan– but at least they have a certain concept.

Alec Soth also has practical advice when it comes to working on a project and trying to find subjects: have a shot list. He shares how he put together concepts of shots he wanted for his “Sleeping by the Mississippi” and “NIAGARA” project. Soth shares also how important is to be flexible and to improvise as well:

“While working on this project I made a trip down the Mississippi River. After awhile I saw the river as a metaphor for this kind of improvisational wandering. I decided to make the river the explicit subject while continuing to play all of these games beneath the surface.”

“I still play these games. Now I usually have a list of subject I’m looking for. With Niagara, for example, this list included things like motels, love letters, couples, and so forth. I feel a bit lost if I don’t have anything specific to search for. But the list is just a starting place. It gets me involved in the landscape. Once I’m engaged any number of things can develop.“

Takeaway point:

I think the beauty of street photography is that much of it is unplanned and spontaneous. We don’t really know what we will get until we hit the streets and go out and shoot.

However if you are working on a certain street photography project or a concept– I think it is good to experiment having some sort of a “shot list.” Have a rough idea of what kind of images you want to shoot, and go out and pursue shooting them. And of course, don’t feel like you should be “married” to your shot list. Feel free to improvise and “go with the flow.”

12. On telling stories

I think Alec Soth is one of the best contemporary story-tellers when it comes to photography. Soth does this by working on project-based approaches, and he shares some more thoughts in detail below:

“This is the never ending struggle, I think storytelling is the most powerful art, for me. I just think there’s nothing more satisfying than the narrative thrust: beginning, middle, and end, what’s gonna happen. The thing I’m always bumping up against is that photography doesn’t function that way. Because it’s not a time-based medium, it’s frozen in time, they suggest stories, they don’t tell stories. So it is not narrative. So it functions much more like poetry than it does like the novel. It’s just these impressions and you leave it to the viewer to put together.”

Soth also brings up the concept of “filling in the dots” when it comes to storytelling:

“One of the things I have in the lecture tonight is the Aristotelian dramatic arc, which shows an actual arc: building tension, climax, resolution. Then I did the photographic equivalent, which is just these dots, all over the place. For the viewer it’s this game of filling in those dots. There’s this struggle of how closely you put the dots together. I never know. Right now I’m experimenting with something else where I’m trying to tell a story, an actual story, for the viewer to figure it out what happens. Still you have to be very careful photographically, so it’s not so obvious. Making those gaps, it’s always the question.”

Takeaway point:

If you a street photographer who wants to work on a more project-based approach, I recommend listening to Alec Soth’s advice (if you want to tell a story). Consider the beginning, middle, and the end of a project in terms of your images, and the flow they tell.

Sequencing and editing is one of the most crucial things when it comes to storytelling in photography– and something that isn’t easy to explain. It is more like poetry you have to go with the flow and feeling of images.

However a way we can better learn storytelling is through movies and plays. Many of these stories can be put into some sort of structure: you start with an opening shot, you are introduced to the characters, the characters go through some sort of trial & tribulation, there is a climax, a resolution, then it ends. Of course not all films go this way– but you can think of the same structure when it comes to your photographic projects.

Therefore when you are editing and sequencing a project, sometimes the best people to ask are people outside of the photographic world: writers, poets, architects, film-makers, actors, or play-wrights.

13. On vulnerability

I think street photography is a lot about vulnerability. Making yourself vulnerable to strangers, and having strangers become vulnerable to you.

I also feel that photography is mostly a self-portrait of who we are, rather than other people. We decide to see the world in a certain way or perspective. This is why we decide to photograph certain things, while deciding not to photograph other things.

Soth shares how personal the act of photographing is:

“…Uncommon Places, is one of the books that changed me. That passage was everything for me, because in the end, it’s all about the process. The fact that he added that piece to that book, I could feel being him, making those pictures, which I think is such a big part of how photography works. One of the ways I see photography as different from conventional storytelling is that in some ways, the photographer is the protagonist. You experience their movement. I could feel it.“

Furthermore Soth builds on the idea of how photography is about vulnerability:

“One thing I’m really interested in is vulnerability. When you talk about Arbus and Hujar . . . I like being exposed to vulnerabilities. I think there’s something really beautiful about it. That’s kind of what I’ve been doing with these little stories, amping up the vulnerability, but also my own vulnerabilities, exposing more of myself. Because I knew with that “journalist” line I’m exposing my own shit there. I’m trying to get down to something raw.”

Takeaway point:

Even though I am a pretty cheery and friendly guy on the outside– deep down, I am quite critical of society. I find this shows through my photography– most of my work is pretty grim and depressing.

I have discovered photography as a way for me to personally cope with the world. To better understand my feelings through the people I photograph.

I also feel when I am on the streets, one of the best ways to connect with strangers is to make yourself vulnerable. I try to always connect with people and share them a little about my personal background and interests in photography before I ask to take someone’s photograph. If people feel comfortable and safe around you, they will be much more likely to agree to be photographed.

Also when it comes to vulnerability– I think it takes a lot of courage to not only photograph, but to also share your work online. Sharing your work online is to make yourself vulnerable. Vulnerable to having people criticize your work or not like it at all.

Making ourselves vulnerable takes a ton of courage– but it is this act of vulnerability which makes street photography so beautiful and open.

14. On creating meaningful work

Alec Soth is not your typical Magnum photographer. When most people think about Magnum, they think about raw, gritty, black & white reportage work in conflict or war zones.

However Soth is more associated with the fine-art world. So what initially drew him to Magnum? It is to find deeper meaning in his work, as he knew that the fine-art world could become self-indulgent:

“I’m often asked why, as a fine-art photographer, I would want to be part of Magnum Photos. In my application letter to associate membership of Magnum, I tried to answer this question by writing:

“I don’t trust art world success. If you look at a twenty-year-old catalogue of the Whitney Biennial, you don’t recognize many names. Moreover, much of the work looks empty, dated and self-indulgent. The truth is that I’m prone to self-indulgence. I could easily see myself holing up in Nova Scotia scribbling hermetic diary notes on old pictures and thinking it is great art. This is the reason I applied to Magnum.”

Soth also shares the importance of creating meaningful images that will stand the test of time:

What unites Magnum photographers is that they go out into the world to make pictures. In twenty years, much fine art photography will be as relevant as this. I suppose a lot of people no longer think Magnum is relevant either. But I disagree. While there aren’t many magazine venues for this kind of photography, the work itself is still important. There are a bunch of younger photographers at Magnum making fantastic pictures. And much of this work will stand the test of time. For example, take a look at Christopher Anderson. His pictures aren’t just important – they’re good. Not only does he do terrific work in hotspots all over the world – he is really good at photographing Republicans:

Soth acknowledges how shallow the art world can be as well:

“The artworld can seem pretty shallow sometimes. I have admiration for working photographers. Photojournalists get a lot of criticism, but they really are brave and sometimes even heroic. Look at this picture of Christopher Anderson carrying an elderly woman through the rubble of Aitaroun, Lebanon (A related article can be read at PDN online).

That said, I’m very aware of the fact that I’m not a photojournalist. The art world is my terrain. I haven’t carried anybody trough rubble lately. I’m just happy to rub elbows with these folks from time to time.“

Takeaway point:

Even though Alec Soth will probably never become a photojournalist or photograph in conflict areas, he still greatly admires the work that they do. And Soth isn’t going to quit the fine-art photography world anytime soon. But he still says he loves to “rub elbows with these folks from time to time” the working photojournalists, to stay grounded in his work. He is leery of the fine-art world success, and how it can become self-indulgent, and not as meaningful.

Personally I have found myself falling into this trap as well. For a long time, I was less interested in the power of photography to change other people’s perspectives and the meaning of it– and more interested in the amount of popularity I would get via social media. Whenever I uploaded an image online, rather than asking myself: “What is the social significance of this image?” or “Will this image stand the test of time?”, I asked myself: “Will this shot get a lot of favorites” or “Will this shot be popular?”

Let us all remind ourselves that our ultimate aim in photography shouldn’t be just to get lots of love on social media– but rather, to create meaningful work. Work that affects, influences, and emotionally touches others.

Conclusion

Even though Alec Soth isn’t a street photographer– I think his background and experience in the fine-art world and working on projects gives us great insights. Alec Soth has personally challenged me to switch from working on single-images to a more project-based approach. He challenged me to go past self-indulgence in photography, and to create more socially meaningful work.

Alec Soth is seriously a photographer’s photographer– and this article doesn’t do justice to how much inspiration he has given me. But I recommend for you to check out more his books, interviews, and features to find out about him. He will easily be one of the most influential photographers in the 21st century and go down in the books of photographic history.

Interviews

- Alec Soth, How You Living?

- A Conversation with Alec Soth

- Dismantling My Career: A Conversation with Alec Soth

Books by Alec Soth

1. From Here to There: Alec Soth’s America

If you can have one book by Alec Soth, this is the one to have. It is a great compilation of his photographic projects, with superb essays included by other photographers and curators. A must-have in your library.

2. NIAGARA

A beautifully bound book, and one of the most poetic books I own by him. The images, sequence, and printing of the book is incredible. Highly recommended.

3. Sleeping by the Mississippi

This book is one of the hardest books to find– and seriously expensive. Also considered his best work. If you can get your hands on a copy, it is an investment you won’t regret.

4. Ping Pong Conversations: Alec Soth with Francesco Zano

A good introduction to Alec Soth’s work– with valuable information. The only book listed that isn’t out-of-print, and a great deal at only $21 USD.