“A bible for photographers” – Clement Cheroux

Wow— where do I even begin? I would say that “The Decisive Moment” by Cartier-Bresson is one of the most beautiful photo books I have ever handled— and it is a book that brings me extreme joy and happiness (you can see all the photos from the book for free on the MagnumPhotos website here).

Sure I have seen many of these photos by Cartier-Bresson before, but to see them in a physical manifestation is a different experience. Not only that, but the original version of “The Decisive Moment” was nearly impossible to get (second-hand copies before the reprint were around $1000+). However now with this re-print by Steidl, “The Decisive Moment” is now open to everybody.

My history with “The Decisive Moment”

Many photographers I know who embarked on street photography (about a decade before I did) always mention “The Decisive Moment” by Cartier-Bresson as a starting point. They all shared how inspired and moved they were by the book, and how it kick-started their journey into street photography.

I had never seen “The Decisive Moment” in person before— but I had already seen almost all of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs online, in other photography books, and on the MagnumPhotos website.

When I first heard about the re-print of “The Decisive Moment” — I was pretty stoked. I don’t know exactly how excited I was to see the photographs in the book (as I already have seen most of them)— but one of the biggest reasons I ordered the book was for the vanity of actually owning the book. And I was curious to see how the book looked, felt, and how the photos were arranged in the book.

I pre-ordered the book several months before, and mostly forgot about it. Then suddenly one day it appeared on my doorstop. Like a kid waiting for his Christmas presents, I tore open the box, and opened it with joy.

My first impression: boy, is this book HUGE. It was a lot bigger than I expected (it measures around two of my hands vertically, and one and a half of my hands horizontally).

Not only that, but I was quite surprised to see that there was an accompanying “pamphlet” which is an introduction to “The Decisive Moment”. In the pamphlet (also huge) was a nice historical backdrop of the printing of “The Decisive Moment”, technical notes, and how the book was put together.

I then started to look through “The Decisive Moment” and was blown away with the quality of the printing. The paper is nice and thick, has a slight cream/ivory color, and the prints of the photographs are unlike anything I have ever seen before. There is phenomenal tonality in the prints— you can see an amazing gradation between the whites/greys/blacks in the prints. There is still detail in the blacks of the photos, and there are no whites that are totally blown out either. Not only that, but the photos are also HUGE. They are a lot bigger than I had ever seen (on my computer monitor), and I really felt the presence of the images.

What I was also fascinated by were the pairings in the book. I had seen the majority of Cartier-Bresson’s images as single-images. But seeing the images paired in the book created a totally new meaning for me. For example, there are certain spreads in the book in which he pairs images of America (adds to the depressing mood), and there are other spreads where he has one vertical photo and two horizontal photos— which make an interesting mosaic.

Not only that, but on the jacket of the book are still the original introductions and reviews from the original copy of “The Decisive Moment”. I literally felt like I was holding a piece of history— which transported me to the past.

I read the entire book cover-to-cover several times from the nice amber light of my desk at home in the evening — and it put me in a mellow and reflective mood. I lived with the images that evening, and went to sleep with an inner-sense of calm.

I am now reviewing this book from one of my favorite cafes in Berkeley (Artis Coffee)— and I want to share some interesting information, history, and lessons from “The Decisive Moment”.

Long story short— I highly recommend the book. Even if you might not have the cash right now, just order a copy of “The Decisive Moment” on your credit card. I’m almost 100% sure this copy will sell out quite quickly, and perhaps a year from now you won’t be able to get a copy for less than $300–400. I could also easily say that this is one of my top–5 favorite photography books of all time.

The creation of “The Decisive Moment”

“While our prints are beautiful and perfectly composed (as they should be), they are not photographs for salons […] In the end, our final image is the printed one.” – Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1951.

When Cartier-Bresson wrote this in 1951, it was quite uncommon for photographers to publish photo books. The majority of photos were printed in magazines, and also shown in exhibitions. Henri Cartier-Bresson shares his frustration for having his photos printed in magazines, and also his need for a book:

“Magazines end up wrapping French fries or being thrown in the bin, while books remain.”

One of his biggest frustrations was the fact that he wasn’t able to sequence and layout his photographs in magazines. He shares his frustration by sharing:

“The words are those of the photographer, but the phrasing is that of the magazine.”

Cartier-Bresson first started to come up with the idea of putting together “The Decisive Moment” in the spring of 1951. On May 4th, Tommy, an assistant at the Magnum Photos office in Paris wrote to Cartier-Bresson in a letter saying that he started to gather a “selection of pix for Watkins […] for the purpose of showing a possible publisher the scope of your book as well as its quality.” Before, Cartier-Bresson was in correspondence with Armitage Watkins, a literary agent based in New York after inquiries from Richard L. Simon from Simon and Schuster Publishing was interested in publishing a book of Cartier-Bresson’s images.

In 1952, Cartier-Bresson started to compile a selection of images from the book— and he wrote to Teriade in two letters:

“I am filing my images and researching in the archive. […] Everything is fine. I found a fair amount of images in my US archive, and I will soon look into the Oriental one.”

In the next few weeks, he started to write an introduction with the help of Marguerite Lang, one of the colleagues of Teriade. At the end of March, the preface was done and translated. Soon after, they prepared three copies of a book dummy. The French edition of “The Decisive Moment” was to be called: “Images a la Sauvette”. Over the Easter holiday in April, Cartier-Bresson showed the book dummy to Matisse, and probably around that time Matisse created the book cover.

The book was printed in July 22nd, and officially released in France and the United States on October 15, 1952.

The collaborative effort of putting together “The Decisive Moment”

One of the things that I learned was how important teamwork was in creating “The Decisive Moment”. In all, there were more than 15 people who collaborated on making “The Decisive Moment”.

To start off, Richard Leo Simon (of the famous publishing house Simon and Schuster) was an amateur photographer with a strong interest in photography and technology. He authored a handbook called “Miniature Photography” which included practical advice for amateur photographers. Simon was fascinated in the work of Cartier-Bresson, in which he referred to him as “one of the great photographers in the world”.

Nancy White (who was the niece of the Editor-in-Chief of Harper’s Bazaar) invited Cartier-Bresson to contact Richard Leo Simon through Armitage Watkins.

The literary agent Armitage Watkins collaborated with Simon and Schuster. At Teriade’s, Marguerite Lang helped Cartier-Bresson with the preface. At Magnum Photos in Paris, Tommy and Robert Muller made the first edit of images and researched the captions. Suzie Marquis (the cousin of Robert Capa), transcribed the introduction and proofread the text. Margot Shore (head of the Magnum Photos Paris office) translated the preface into English. Armel Gourvil and Lionel Birch (the first husband of Inge Morath) also helped with translations. At Magnum Photos in New York, Pat Hagan and Robert Capa closely watched over the project. At Pictoral service, Pierre Gassman supervised tests and printing for the first 3 book dummies and prepared the glass plates for the heliogravure printing at Draeger’s— and the Draeger brothers printed the book. Matisse designed the cover.

So you can see that when putting together a photography book (especially as great as “The Decisive Moment”)— it is truly a collaborative effort. Something to think about when you plan on putting together your own photography book. Think about the people you need to help you design the cover, with the text in the book, with the selection and layout, and the final printing of the book.

The cover of “The Decisive Moment” by Matisse

One of the most striking things about “The Decisive Moment” is the cover by Matisse. It is a bit ironic that the cover of a photography book is a design by Matisse, who was famous for his paper gouache cutout technique.

The original cover of the book measures 36x57cm and it includes several symbolic elements. In the upper-right corner, you have a bright sun— with a line of blue mountains in the background. In the middle, you can see a bird holding a branch of cineraria in its beak, and in the bottom you can see a few green or black vegetative-forms and a diamond shape (which could be a stone or a puddle of water). And in the bottom of the cover, you can see the elegant calligraphy of Matisse, who funny enough forgot the hyphen between “Cartier” and “Bresson”.

The back cover includes green and blue spirals and speckles in-between. According to curator Dominique Szymusaik, they were meant to evoke “the pace of time”.

Whatever the symbolism of the cover and back-cover, it has a beautiful and classic look. I could almost imagine cutting out the cover and framing it just as a print. I think the cover of “The Decisive Moment” is one of the major elements that make it truly feel like a work of art.

The dimensions of “The Decisive Moment”

I also found it interesting how the dimensions of “The Decisive Moment” were quite intentional. The book is vertical, and measures 37×27.4cm— which was a size proportional to the 24×36 film used by Cartier-Bresson.

The biggest advantage was this: it allowed the full spread of one horizontal photograph or two vertical photos on a double page. The original paper was a luxurious matte paper called “Helio Afnor VII” — which was the highest quality standard for paper-makers. The book comprised of 156 pages, and the high standard of printing blew people away. Walker Evans called the book having a “breathtaking quality”— and William Eggleston explained the following:

“I had picked up ‘The Decisive Moment’ years ago when I was already making prints, so the first thing I noticed was the tonal quality of the black and white. There were no shadow areas that were totally black, where you couldn’t make out what was in them, and there were no totally white areas. It was only later that I was struck by the wonderful, correct composition and framing. This was apparent through the tones of the printed book. I later found some actual prints of the same pictures in New York. They were nothing— just ordinary looking photographs, but they were the same pictures I had worshipped and idolized, yet I wouldn’t have given ten cents for them. I still go back to the book every couple of years and I know it is the tones that makes the composition come across.”

Layout of “The Decisive Moment”

The layout and sequencing of the book is as follows:

The book opens with an introduction by Henri Cartier-Bresson, which is followed by along sequence of pictures, a few pages of captions, then a second set of pictures, once again ending with more captions. In the American version, there are technical notes at the end of the book by Simon.

In terms of the templates in the layout, there are 4 types:

- 28 double-pages with two vertical photos (the most common layout)

- 19 double-pages which show only one photograph (horizontals)

- 13 double-pages that show three photographs (one vertical and two horizontal)

- 2 double-pages with four horizontal photographs.

The layout of the book is simple and elegant— and it works. For the pages with the double-pages with the two vertical photos— the photographs generally have a commonality between them. With the double-pages with only one horizontal photograph, they tend to be strong single-images that demand respect. The double-pages with three photographs create a nice mosaic that adds to the flow of images, and the 2 double-pages with four horizontal photographs create a nice collage as well.

Sequencing of “The Decisive Moment”

In terms of the sequence of “The Decisive Moment” — there are two major sections. The first section includes 60 pages, and the second section includes 68 pages. Both sections include 63 images.

The sequencing of images is mostly chronological. The first section of photographs is mostly between 1932–1947. The second section mostly includes photos from 1947–1952.

The first section seems to be Cartier-Bresson’s more “artistic” photos— and the second section is most of his photojournalistic images.

The first section includes images from France, Europe, Mexico, and the US. The second section includes images from India, Indonesia, China and the Middle East. In the American version of “The Decisive Moment” — the table of contents shows an “Occidental section” and an “Oriental section”.

Titles for “The Decisive Moment”

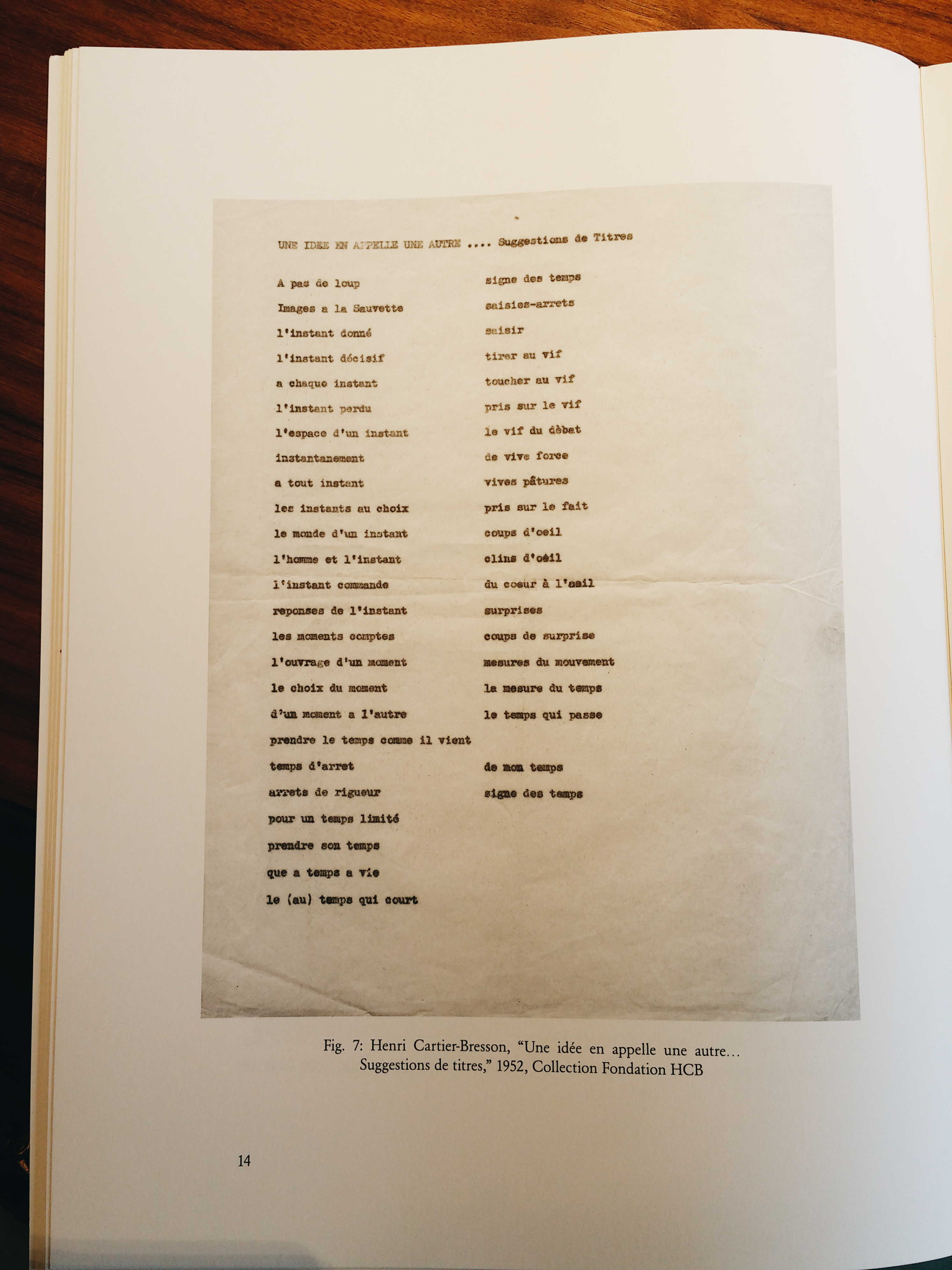

Another thing I found fascinating about “The Decisive Moment” is all the potential titles Cartier-Bresson brainstormed. Apparently many of the titles that he first came up with were inspired from Voltaire, Buffon, Racine, Corneille or Pascal— with some of the titles dealing with the notion of “time”.

Cartier-Bresson came up with 45 titles — here is a breakdown of the concepts he included:

- 12 dealt with “instant”

- 11 dealt with “time”

- 6 dealt with “vivacity”

- 4 dealt with the “moment”

- 3 dealt with the “eye”

The first title he initially came up with is “A pas de loup”— which means “tiptoeing”. This reflected how Cartier-Bresson would approach his subjects, as he wrote in the preface: “The subject must be approached tiptoeing.” The second suggestion was “Images a la Sauvette”. Apparently the expression is related to when small street vendors have to run away when being asked for their licenses. The French title was ultimately chosen as “Images a la Sauvette”.

When they came up with the French title, they also had to come up with an English title. Ultimately they gained inspiration from Jean-Francois Paul de Gondi (also known as “Cardinal de Retz”) who said:

“There is nothing in this world that does not bear a decisive moment.”

This was a great phrase— as it perfectly described how Cartier-Bresson described his photography. To define “the decisive moment” — this is what Cartier-Bresson said:

“In the span of a fraction of a second, the simultaneous acknowledgement of the meaning of a fact on one hand, and on the other, of a rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that express this fact.”

Preface text of “The Decisive Moment”

One thing that is lovely about “The Decisive Moment” is that there is a “how-to” photography guide in the beginning of the chapter. In the chapter, he covers the following topics:

- How he got started in photography

- The picture-story

- The subject

- Composition

- Color

- Technique

- The customers

Here are some of my favorite quotes from each section:

How he got started in photography

Cartier-Bresson on how he is still fascinated by photography:

“Twenty-five years have passed since I started to look through my view-finder. But I regard myself still as an amateur, though I am no longer a dilettante.”

The picture-story

Cartier-Bresson on the importance of combining the eye and soul to making a moving picture-story:

“The picture-story involves a joint operation of the brain, the eye and the heart. The objective of this joint operation is to depict the content of some event that is in the process of unfolding, and to communicate impressions. […] You must be on the alert with the brain, the eye, the heart; and have a suppleness of body.”

The subject

On how the little things can make great subjects:

“In photography, the smallest thing can be a great subject. The little, human detail can become a leitmotiv.”

Composition

Cartier-Bresson on the importance of form and communication:

“If a photograph is to communicate its subject in all its intensity, the relationship of form must be rigorously established. Photography implies the recognition of a rhythm in the world of real things. What the eye does is to find and focus on the particular subject within the mass of reality; what the camera does is simply to register upon film the decision made by the eye.”

Cartier-Bresson on the importance of slight modifications to make stronger compositions:

“The photographer’s eye is perpetually evaluating. A photographer can bring coincidence of line simply by moving his head a fraction of a millimeter. He can modify perspectives by a slight bending of the knees. By placing the camera closer to or farther from the subject, he draws a detail— and it can be subordinated, or he can be tyrannized by it. But he composes a picture in very nearly the same amount of time it takes to click the shutter, at the speed of a reflex action.”

Cartier-Bresson on patience in photography:

“Sometimes it happens that you stall, delay, wait for something to happen. Sometimes you have the feeling that here are all the makings of a picture— except for just one thing that seems to be missing. But what one thing? Perhaps someone suddenly walks into your range of view. You follow his progress through the viewfinder. You wait and wait, and then finally you press the button— and you depart with the feeling (though you don’t know why) that you’ve really got something.”

Cartier-Bresson on the importance of geometry and composition in a shot:

“Later, to substantiate this, you take a print of this picture, trace on it the geometric figures which come up under analysis, and you’ll observe that, if the shutter was released at the decisive moment, you have instinctively fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would have been both formless and lifeless.”

On shooting with intuition (and analyzing compositions after you’ve shot them):

“Composition must be one of our constant preoccupations, but at the moment of shooting it can stem only from our intuition, for we are out to capture the fugitive moment, and all the interrelationships involved are on the move. In applying the Golden Rule, the only pair of compasses at the photographer’s disposal is his own pair of eyes. Any geometrical analysis, any reducing of the picture to a schema, can be done only (because of its very nature) after the photograph has been taken, developed, and printed— and then it can be used only for a post-mortem examination of the picture. I hope we will never see the day when photo shops sell little schema grills to clamp onto our viewfinders; and that the Golden Rule will never be found etched on our ground glass.

Henri Cartier-Bresson against cropping:

“If you start cutting or cropping a good photograph, it means death to the geometrically correct interplay of proportions. Besides, it very rarely happens that a photograph which was feebly composed can be saved by reconstruction of its composition under the darkroom’s enlarger; the integrity of vision is no longer there. There is a lot of talk about camera angles; but the only valid angles in existence are the angles of the geometry of composition and not the ones fabricated by the photographer who falls flat on his stomach or performs other antics to procure his effects.”

Cartier-Bresson on the importance of content and form:

“For me, content cannot be separated from form. By form, I mean a rigorous organization of the interplay of surfaces, lines, and values. It is in this organization alone that our conceptions and emotions become concrete and communicable. In photography, visual organization can stem only from a developed instinct.”

Color

Cartier-Bresson on sharing that shooting color requires a different mindset from shooting black and white:

“Though it is difficult to foresee exactly how color photography is going to grow in photo-reporting, it seems certain that it requires a new attitude of mind, an approach different than that which is appropriate for black and white. Personally, I am half afraid that this complex new element may tend to prejudice the achievement of the life and movement which is often caught by black and white.”

Technique

Cartier-Bresson on the importance of knowing enough technique to simply create the photos you want to create (and communicate what you see):

“Technique is important only insofar as you must master it in order to communicate what you see. Your own personal technique has to be created and adapted solely in order to make your vision effective on film. But only the results count, and the conclusive evidence is the finished photographic print; otherwise there would be no end to the number of tales photographers would tell about pictures which they ever-so-nearly got— but which are merely a memory in the eye of the nostalgia.”

Cartier-Bresson on not encouraging us not to care too much about technical details:

“It is enough if a photographer feels at ease with his camera, and if it is appropriate to the job which he wants it to do. The actual handling of the camera, its stops, its exposure-speeds and all the rest of it, are things which should be as automatic as the changing of gears in an automobile. It is no part of my business to go into the details or refinements of any of these operations, even the most complicated ones, for they are all set forth with military precision in the manuals which the manufacturers provide along with the camera and the nice, orange calf-skin case. If the camera is a beautiful gadget, we should progress beyond that stage at least in conversation. The same applies to the how’s and whys of making pretty prints in the darkroom.”

The customers

Cartier-Bresson on the judgment calls we need to make as photographers:

“We photographers, in the course of taking pictures, inevitably make a judgment on what we see, and that implies a great responsibility.”

Cartier-Bresson on presenting your work in different ways:

“There are other ways of communicating our photographs than through publication in magazines. Exhibitions, for instance; and the book form, which is almost a form of permanent exhibition.”

On life

Cartier-Bresson on living and photography:

“I believe that, through the act of living, the discovery of oneself is made concurrently with the discovery of the world around us which can mold us, but which can also be affected by us. A balance must be established between these two worlds— the one inside us and the one outside us. As the result of a constant reciprocal process, both these worlds come to form a single one. And it is this world that we must communicate.”

My personal review of “The Decisive Moment”

For purely historical purposes, I highly recommend every street photographer pick up a copy of “The Decisive Moment”. Not only that, but as a physical object— it is beautiful. The book itself is a work of art.

The common question I have been getting from other photographer is this: “If I have already seen Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, is it worth it to get the book?”

I would say a resounding yes. The reason is that I don’t think photography is purely about seeing an image as a visual form. I think photography is also about looking at a photograph in different ways— and experiencing the photograph in different ways.

For example, I have seen Cartier-Bresson’s photographs online, in exhibitions, and in books— and the emotional response I get from the images always changes. I experience a photograph differently from when I hold it, from when I see it in a book, or see it printed big on a wall for an exhibition.

I would say the experience is the difference between reading a book on an e-reader versus actually on a book-form. Sure the information is the same, and the e-reader is more convenient, but the experience of holding a physical book, smelling the pages, flipping through it, bookmarking it, highlighting certain pages— is something you can’t fully replicate digitally.

In terms of the actual book— I would certainly say I prefer the first half of “The Decisive Moment” to the second half. In the first half are his more “artistic” photographs that is he is famous for. The second half of the book is more of his photo-reportage that he did around Asia and India— and I don’t think it has the same artistic charm as the other work he did in Europe and the states.

But in-conclusion, this is a book you don’t want to miss out on— it is worth every penny.

You can also see all of the images from “The Decisive Moment” for free on the MagnumPhotos website here.

Other books by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Below are the books I highly recommend on Henri Cartier-Bresson:

- Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Mind’s Eye (only $15, a book of his philosophies. Highly recommended)

- Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century ($50, a good retrospective on HCB’s life and work)

- Henri Cartier-Bresson: Scrapbook ($75, a unique look into HCB’s working process and personal work. Highly recommended)

Learn more about Henri Cartier-Bresson

If you want to learn more about Henri Cartier-Bresson, I recommend these articles:

- 17 (More) Lessons Henri Cartier-Bresson Has Taught Me About Street Photography

- 10 Things Henri Cartier-Bresson Can Teach You About Street Photography

Street photography book reviews

If you want to check out some more street photography book reviews, I recommend you read the following:

- Magnum Contact Sheets

- Dan Winters: Road to Seeing

- Alex Webb: The Suffering of Light

- Josef Koudelka: Gypsies

- Robert Frank: The Americans

- Martin Parr: The Last Resort

- Trent Parke: Minutes to Midnight

- Photographers’ Sketchbooks

- The Photobook: A History Volume III

You can also see the full list of street photography books I recommend here.