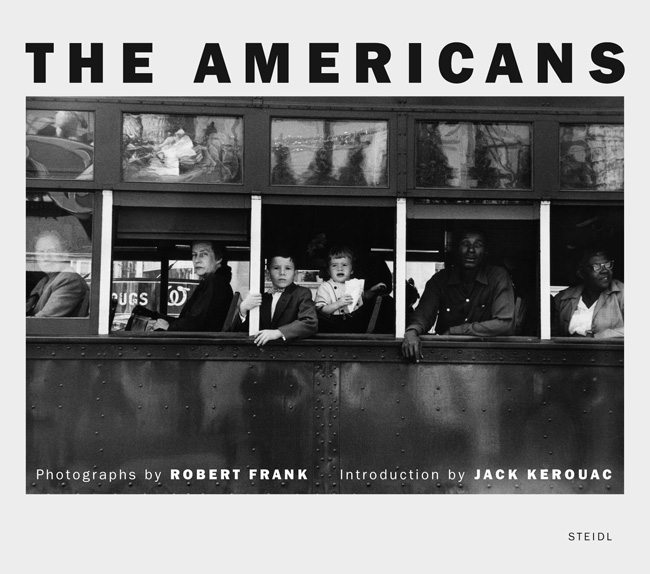

“The Americans” by Robert Frank is one of the most influential photo books published of all-time. It has inspired countless numbers of photographers across all genres, especially appealing to documentary and street photographers. I know the book has had a profound impact on my photography and how I approach projects.

While I am not an expert on Robert Frank or “The Americans”, I will share what I personally have learned from his work. For your reference, I used Steidl’s “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans” as a primary resource for this article. The article is incredibly long, and I encourage you to read it not all in one sitting, but in different phases.

I would also highly recommend saving this article and reading it on Instapaper or Pocket. These services allow you to save the article to read later on your phone, iPad, computer, etc.

Introduction

“The Americans” is a photography book by Swiss-born Robert Frank, published first in France (1958) and then in the US (1959). It consisted of 83 photographs, with only one photograph per page. I am certain that many of you are familiar with Robert Frank and “The Americans”. But for those of you who are not as familiar with “The Americans” let’s address why it was so important and influential.

Why was “The Americans” so influential?

“The Americans” was influential for several reasons. I will try my best to outline why I perceive it to be so influential:

1. It challenged the documentary tradition

During the era that Frank published “The Americans”, documentary photography was seen to be as something transparent and not to be influenced by the thoughts, emotions, or viewpoint of the photographer. A quote from the book on “Looking In: The Americans”:

“In the late 1950s and early 1960s neither The Americans nor Frank’s work made on his Guggenheim fellowship were well received, especially by the photography press. Edgy, critical, and often opaque at a time when photography was generally understood to be wholesome, simplistic, and patently transparent, the photographs disconcerted editors even before the book was published.”

When Robert Frank worked on the Americans, consider it from his viewpoint. He was Swiss-born, and he saw America from an outsider perspective. Although his work was a labor of love, he clearly showed the ugly parts of American society, which included mass consumerism, racism, and the divide between the rich and poor.

Frank was clear in saying that his work was a personal account of America, as he mentioned in U.S. Camera Annual 1958. Frank shared that the book was “…personal and, therefore, various facets of American society and life have been ignored.”

Through “The Americans” Frank wanted to highlight the darker side of America which hadn’t been shown before.

2. It challenged the aesthetic of photography

During the 1950’s, the tradition and aesthetic of photography championed clean, well-exposed, and sharp photographs. Technical perfection was considered king. However in Frank’s “The Americans”, he was first harshly criticized by critics saying things like the prints were “Flawed by meaningless blur grain, muddy exposure, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness”.

Not only that, but critics would see Frank as having “contempt for any standards of quality or discipline in technique.” To better understand where Frank got his gritty aesthetic from, let us explore a bit of his background: When Frank started photography in his early twenties, he studied with Alexey Brodovitch, a Russian-born innovator for Harper’s Bazaar. Brodovitch was well known for turning the magazine from having drab and boring photographs and adding dynamic montages of photos and text.

What Frank learned from Brodovitch was “to respond to situations not analytically or intellectually but emotionally and to create highly original works of art that reflected their personal respond to their environment.”

Therefore Frank learned that in order to create emotional photographs, he needed to experiment with different techniques in photographing, printing, and presenting his work. Brodovitch was experimental, and “encouraged students to use blur, imprecise focus, large foreground forms, bleach negatives, radically crop and distort print, or print two photographs on top of each other, put gauze over lens of enlargers – to not capture facts of scene but to experience it.”

This mentorship from Brodovitch had a strong influence on the young Robert Frank. From his work leading up to “The Americans”, he did very much that. He would often shoot at night using imprecise focus, incorporated blur into his work, and would use grainy film. Not only that, but Frank experimented printing his photographs with extreme contrast (disregarding the need to create an image with good tonal range), printing in extreme shapes (trapezoids), and would crop radically.

Therefore when Frank shot “The Americans”, he kept those same aesthetics. If you look closely at his contact sheets, many of his photographs were either too bright, too dark, so off-balance, and out-of-focus that “Frank seems at times not even to have looked through the viewfinder or bothered to check the controls on his camera.”

Frank certainly did this with the purpose to better convey the feelings that he had about America– the dark, alienating, and foreign. Not only from Brodovitch, but he also had many other influences from his study of abstract expressionist painters such as Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning. From them he learned the following:

“[Frank] had learned about the relationship between tone and scale to the sensation of weight, and he recognized that shadows or out-of-focus forms need not be legible – could even approach abstraction – and still be highly evocative. With this understanding, his photographs became not merely unclear in their subjects and casual in their style but also potent, deeply haunting, and deliberately ambiguous.”

Therefore through this examination of his studies with Brodovitch and his inspiration from abstract expressionist painters such as Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning, he used this gritty aesthetic deliberately for “The Americans”.

Did it piss off the critics? It certainly did, who simply thought that Frank was being sloppy and lacking technique. But it was through his experimentation and going against the grain of the style of what everyone was photographing at the time — did he create a meaningful and memorable project.

3. It challenged the rules of photography, and emphasized feeling

Not only did Frank challenge how he approached documentary photography and the aesthetic in which he employed– he also created images with an emphasis on feeling above all else. Frank says this about his own work:

“The photograph must be the result of a head to head, a confrontation with a power, a force that one interrogates or questions.”

To create images that are docile and straightforward aren’t enough for Frank. Rather, he wants to create images that are full of power, energy, and ask questions. He didn’t want to create a “picture that really said it all, that was a masterpiece.” Rather, he would try to create images that he would gain feeling and emotion from the photos. An excerpt from “Looking In” also shows the challenge that Frank faced at the time:

“Rebelling against the popular 1950s notion championed by Edward Steichen and others that photography was a universal language, easily understood by all, he wanted a form that was open-ended, even deliberately ambiguous– one that engaged his viewers, rewarded their prolonged consideration, and perhaps even left them with as many questions as answers.”

Therefore in “The Americans”, he didn’t want to create simply a straightforward documentation of America that was more “objective”. Rather, he took very subjective photographs that challenged the viewers of “The Americans” to ask themselves what they were looking at — and to challenge their own views and prejudices about America.

4. It focused less on the “single image”

When Robert Frank decided to start shooting “The Americans”, “straight photography” was the favored style – in which single images, not projects, were king. “Looking in” elaborates:

“‘Straight’ photography was a favored term when both men began to photograph. A Linchpin of “modern” photography, in the United States at least, this approach emphasized relatively un-manipulated prints made form a single negative, with glory given to the work that summarized an instant into a supreme moment of beauty of human understanding. [Frank didn’t pledge] allegiance to such “pure” photography, in which a single, great exposure was the ultimate achievement“.

Therefore by working on this project, Frank was less interested about creating single powerful images (as many photographers on social media do nowadays as well). Rather, he was more interested in creating a strong body of work in which his interpretation of America wouldn’t be summed up in a single image- but rather through all of his images as a collective.

Why Frank Decided To Shoot “The Americans”

Frank was born in Switzerland to a middle-class family and secured solid photography training there. His early influences were some of the most important Swiss photographers, editors, and designers such as Arnold Kubler, Gotthard Schuh, and Jakob Tuggener.

Although he had great inspirational figures in Switzerland Frank reported:

“I wanted to get out of Switzerland. I didn’t want to build my future there. The country was too closed, too small for me.”

Therefore he embarked on a journey to America, and spent a considerable amount of time in NYC, where he met some of the most influential photographers and curators at the time including Andre Kertesz, Walker Evans, Louis Faurer, and Edward Steichen.

However in around 1953, Frank became discouraged after wandering and shooting the streets of NYC for about 6 years. One of his main frustrations was that he couldn’t get his photographs published more widely. For example, he would often be rejected by LIFE magazine to publish his work. Frank shares his frustrations and his disdain for the stories made for LIFE:

“I developed a tremendous contempt for LIFE, which helped me. You have to be enraged. I also wanted to follow my own intuition and do it my own way, and to make concessions – not make a LIFE story. That was another thing I hated. Those goddamned stories with a beginning and an end. If I hate all those stories with a beginning, a middle, and an end then obviously I will make an effort to produce something that will stand up to those stories but not be like them”.

Not only that, but he was also rejected when he applied for membership to the prestigious Magnum Photo Agency. After a brief hiatus in Switzerland, he went back to the states and said, “This is the last time that I go back to New York and try to reach the top through my personal work.”

What ensued afterwards was history. Through support from Walker Evans, Edward Steichen, and Alexey Brodovitch – he applied for a Guggenheim fellowship to make a book on America to reveal “the kind of civilization born here and spreading elsewhere.” With great fortune, he became the first European-born photographer to be awarded the Guggenheim in 1955.

When Frank embarked to photograph “The Americans”, he traveled over 10,000 miles across 30 states in 9 months. Upon returning to New York in the June of 1956, he spent nearly a year developing his 767 rolls of film, making contacts sheets from which he made 1000 work prints. After that, he refined his selection and then established the sequence for the book.

Frank’s Early Inspirations

Before Frank went on to shoot “The Americans” he learned many lessons from his mentors.

1. Lessons from Walker Evans (on working in a methodological manner)

Walker Evans, the already famous photographer for taking his “American Photographs” book was one of Frank’s early mentors. Not only did Evans champion Frank’s work, but Frank learned many lessons from him (although their styles were quite different). Frank worked in a very sociological, methodological manner – often utilizing a large-format camera and wanted to create transparent and “objective” photographs. On one account, when Frank went out to shoot with Evans, Frank noted how it was important to be more reflective (rather than spontaneous) when photographing.

However at the end of the day, Frank shot much more with with emotion and feel – utilizing a small Leica rangefinder, which was more sporadic and vigorous.

“Looking In” mentions the difference between Evans’ and Frank’s working styles:

“Evans had also photographed people in the south, but he had often gotten to know them first, as in his work with James Agee for their celebrated book ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’ (1941). Frank made no similar effort and rarely conversed with the people he photographed, for despite what was written in his Guggenheim application, his intention was not sociological, analytical, or documentary. Responding to the country, as he later said, not by “looking at it but by feeling something from it.”

Frank acted very much like the detached observer when photographing, and didn’t strive to make a sociological or analytical view like Evans did. Rather to Frank, the feeling that the viewer got from the photograph was the most important.

Takeaway point: It is important for us to know our own tendencies (in terms of our shooting styles) whether we tend to be more contemplative or sporadic. We should strive to balance ourselves out. For example, if we tend to photograph slowly, we can gain skill by trying to photograph quicker. If we are much more sporadic and vigorous when shooting street photography, we should slow down and try to be more contemplative. But at the end of the day, it is important to know your true self and style – and stick mainly with it.

2. Lessons from Henri Cartier-Bresson (on inspiration, influences, and originality)

When Frank first moved to NYC, one of the first photography exhibitions he saw was by Henri Cartier-Bresson at the MOMA. Cartier-Bresson’s work had a huge impact on Frank that challenged him to take his photography to the next level. “Looking In” shares:

“Frank quickly learned from and assimilated new influences, often only to turn against them after extracting that all he found useful, a pattern that repeated itself throughout his life. Within the first three weeks of his arrival in New York, he visited the Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, among the last of the exhibitions that Beaumont and Nancy Newhall organized here. Frank was deeply impressed, it challenged him to become more than a fashion photographer.

Furthermore Cartier-Bresson’s exhibition showed Frank the power of photography and how many opportunities it presented:

Frank said later that seeing that exhibition “Was a very good instruction.” He saw that the field of photography was much broader and more open to him, continuing: “I had the feeling that I could do something else. I just saw possibilities. I wanted to try them and do them.”

Although Frank obtained a great deal of inspiration from Henri Cartier-Bresson, he still felt it was important to have his own vision. He also touches on how equipment wasn’t as important as creating your own unique work. Frank says:

“To do good work you need a further intelligence. And you can’t just imitate a famous 35mm photographer. Cartier-Bresson won’t help, wide-angle lenses won’t help either.”

Takeaway point: Therefore to sum up, Frank believed the importance of having role models and other photographers to draw inspiration from. However he realized that merely imitating their aesthetic or using the focal lengths that they used wouldn’t create interesting or unique art. So don’t try to simply imitate photographers you look up to. Draw inspiration from them, but strive towards your own vision. Oh yeah, and having certain cameras or lenses will do little in creating unique work (they knew that even half a century ago).

3. Lessons from Edward Steichen (on getting closer to your subjects / keeping your photography and income separate)

Edward Steichen, one of the most influential and important photographer curators of all time gave the young Frank lots of great advice when it came to his photography. In a letter dated April 2, 1952 Steichen advised Frank the importance of getting closer to his subjects, not just physically but emotionally:

“I sometimes feel that I would like to see you more in closer to people. It seems to me that you are ready now to begin probing beyond environment into the soul of man. I believe you made a fine decision in taking yourself and family away from the tenseness of the business of photography there. You must let every moment of the freedom you are having contribute to your growing and growing. Just as the microscope and the telescope seek a still closer look at the universe, we as photographer must seek to penetrate deeper and closer into our brothers. Please excuse if this sounds like preaching. It is dictated by an interest and affection for you and yours.”

Steichen saw Frank’s strength at capturing the environment and mood of his subjects, but stressed the importance of getting to know “the soul of man”. Steichen only thought it would be possible for Frank to do this by spending more time getting in-depth with the subjects that he captured, to get to know the small nuances and what made his subjects unique.

After hearing this advice, Frank was inspired to go to Caerau, Wales in 1953, where he photographed a miner named Ben James for several days. Frank lived with him in his home and photographed his entire day. Frank would rise with him, follow him to work, even late into the night. This would be great early training in the early tradition of documentary photography to help him immerse himself into his “Americans” project.

Steichen also gave Frank some practical advice with his photography (that carries lots of practical value today as well) on not doing photography full-time. That is, to practice photography on the side while getting a source of income elsewhere. Steichen stressed the importance of getting an income elsewhere to keep photography separate from the need to earn a living – to truly focus on the photography without any constraints. As Frank recalled, Steichen told him the following:

“It is better to be a plumber in the daytime so you can be a photographer at night time.”

Takeaway point: Although Frank didn’t entirely listen to Steichen (for the rest of his career he pursued video-making and his photography) I think it carries great value for photographers today. Many of us don’t have the luxury or the chance to pursue our photography full-time. Although many of us dream of making our photography a living, Steichen’s advice of keeping your photography and work separate carries strong weight. Don’t think that your day job prevents you from creating strong photographic work – rather see it as something that will help support you and in your photography.

4. Lessons from Brodovitch (on equipment and taking risks)

When Frank was a young photographer, he shot mostly with a medium-format square-format Rolleiflex camera. However Alexey Brodovitch, a Russian-born photographer, designer and instructor (who Frank looked up to) suggested him to ditch the Rolleiflex for a 35mm Leica. Brodovitch suggested that the Leica could create more fluid, immediate images, whereas the Rolleiflex was much slower and bulkier by comparison.

Furthermore, Brodovitch encouraged Frank to “unlearn his methodological Swiss habits and taught him to take risks”. You can see that Frank took up Brodovitch’s advice by leaving his comfortable home of Switzerland to pursue photography in NYC.

Takeaway point: You don’t need to shoot with a Leica to be a great street photographer. However at the time, the Leica was the smallest, most maneuverable, and quickest camera to use. Therefore in today’s terms, I would advise against using a bulky DSLR and perhaps using a more nimble camera like a Micro 4/3rds, compact camera, or even an iPhone. Of course you can still create great work with a DSLR but note that it may weigh you down.

How Frank Prepared his Trip to Photograph “The Americans”

For those of you who are curious how Frank prepared his trip to photograph “The Americans” below is a rough itinerary of what he prepared:

- Gathered maps and itineraries from the American Automobile Association

- Collected letters of reference from the Guggenheim Foundation and friends in the press (in-case people questioned his photographing intentions)

- Introductions to representatives to industries around the country (to capture a wide variety of images)

- Suggestions from fellow photographers of places to visit

- Walker Evans: The Souh

- Ben Schultz and Todd Walker: Los Angeles

- Wayne Miller: San Francisco

Frank also prepared some symbols that he wanted to pursue/capture:

- Flags

- Cowboys

- Rich Socialites

- Juke-boxes

- Politicians

Frank also numbered his rolls of film in chronological order and labeled according to location. He also sometimes labeled his film according to subject matter.

Subject matter that Frank Ended up Photographing

Below are some re-occurring subjects that he ended up photographing in his trips around the U.S.

1. Cars (photos. 77, 78, 80)

Frank saw how cars isolated people, separated them from surroundings.

2. American Lunch Counters (photo. 69)

Frank was fascinated by American Lunch Counters, especially how strangers would sit next to each other while eating. This was something very different from what Europeans would do.

3. Consumerism

When traveling around the states, Frank was surprised to see how powerful the role of consumerism culture was in American life. He saw the over-abundance of choices, with people constantly bombarded by signs, cards, newspapers, magazines, and advertisements.

4. Suburbs

Frank was interested in the suburbs, in the sense of how Americans were becoming much more solitary in nature. For example a photograph he took of a drive-in movie theater in a Detroit suburb showed the lonely beauty of watching a movie alone by yourself. Whereas in the past watching a movie was done side-by-side others in a communal type-of-way.

5. Public parks

Frank was drawn how in public parks people would mix in together, and also be totally unaware of his camera.

6. Cemeteries (photos. 80, 74)

Frank photographed several cemeteries in his journeys, and tried to capture their emotional resonance and somberness.

7. Juke-boxes (photos. 17, 65, 67, 43)

Frank found the jukeboxes to be quite hypnotic – and expressive of the allure of American music.

The Working Style of Robert Frank

When Frank photographed “The Americans”, he learned much of his working style from Walker Evans. An excerpt from “Looking in” which shows how Frank learned to be much more patient when photographing from Evans:

“When Frank helped Evans photograph tools for Fortune, he “learned what it is to be simple” and “to look at one thing and look at it very clearly and in a final way”. Frank was impressed with Evan’s careful observation of his subjects and his patience in waiting until the light revealed the scene exactly as he wanted to picture it. Although patience was never an attribute Frank valued or cultivated, keen observation and simplicity proved invaluable to him in the coming months.”

Although Frank discovered the importance of being patient in his working methods, Frank was also more intuitive and photographed quite swiftly. In the excerpt below it explains how he would take several exposures decisively and work quite fluidly:

“The year before, when he had photographed cowboys at Madison square garden or socialites at the toy ball, he had made many exposures of the people and the scenes that interested him, no doubt hoping that an editor would find one of use. But now, with the knowledge that he had plenty of materials, a full year to work on the project, and no one to please but himself, he responded more immediately and intuitively. He took one, two, or three exposures, swiftly, surely, and decisively, and then moved on, for he recognized, “First thought, best thought…When one releases a second time, there is already a moment lost.”

Over time when Frank worked on “The Americans” his working style evolved into being much more graceful and casual. “Looking in” elaborates on this point:

“In the coming months, as he gained more confidence in his new approach and worked himself into what he later referred to as a “State of grace”, Frank’s style became looser, more casual, even gestural, and all about movement. […] Frank photographed his subjects with their backs to the camera, their faces partially obscured, or looming ominously in the foreground, as if they were about to turn and confront him (photos 29, 32).

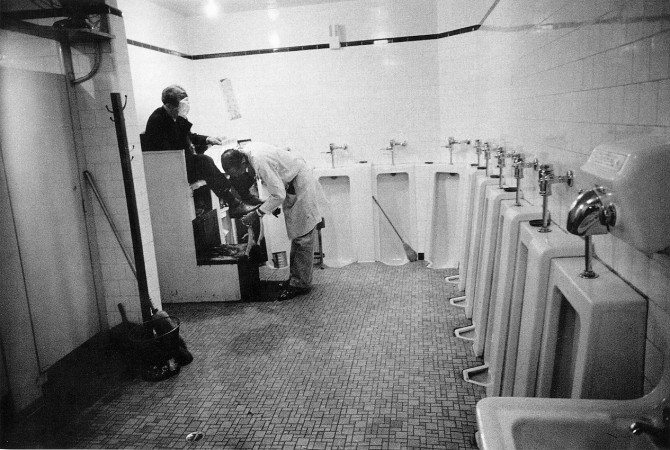

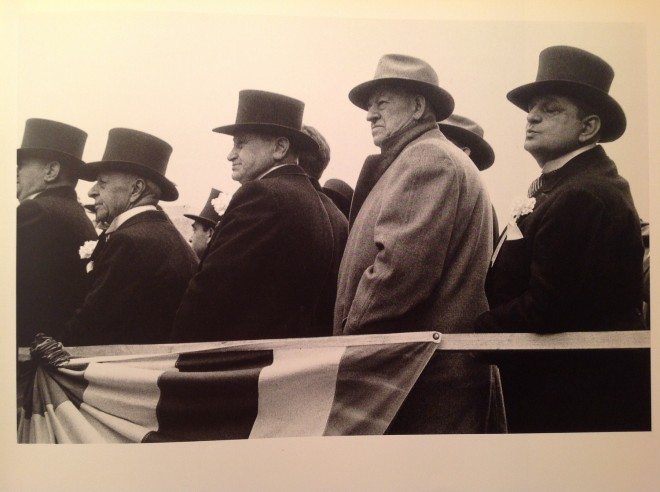

How Frank Captured The Disparity of Wealth/Racism in America

One of the most poignant themes that Frank pursued in “The Americans” was the disparity of wealth in America, as well as the blatant racism. One of the subject matters that hadn’t been explored much during his period was the rich. He didn’t want to just photograph the poor and the middle class – as he wanted to paint a fuller-picture of the American socio-economic classes.

However the difficulty he found in photographing “the richer people, the upper class people” was that they were more difficult to find and photograph. Whereas the poor and the middle class would often be out in the open, the rich would be more secluded, behind closed doors. To locate and photograph the rich, he focused on finding them at movie premieres and balls where the wealthy were abundant.

When it came to capturing racism, he had a difficult time to convey this concept through his photographs. He first started off much more objectively, photographing signs of water fountains that said “white” and “colored”. “Looking-in” shares:

As they traveled from Norfolk to Richmond, Virginia, to Charlotte, North Carolina, Frank was “amazed” by the discrimination he saw. Although he had lived in New York for several years and had traveled to St. Louis and Kansas City, nothing prepared him for the rigid segregation of the south, which he described as “totally a new experience”. His contact sheets show that he initially addressed the issue of segregation by photographing the signs for “white” and “colored” water fountains or waiting areas that he frequently encountered.

However as Frank went deeper into the south, he realized more nuanced ways to capture racism through his photos that weren’t “too clear”. He did this in different ways by juxtaposing the living conditions of the wealthy whites and the poverty-ridden African Americans. He also became to admire the struggling African Americans much more than their wealthy counterparts:

But as he ventured deeper into the south, and his objectives became increasingly layered and nuanced, he rejected these easier, more obvious solutions as “too clear” and “banal”. He came to understand that he wanted not only to comment on the pervasive presence of racism but also to reveal the affinity he felt for African Americans and to celebrate their openness and lack of suspicion compared to the Caucasians he encountered.

How Frank Edited and Sequenced “The Americans”

1. What Frank learned about editing/sequencing/bookmaking:

a) How Frank learned how to group photos by subject matter

Before Frank shot “The Americans” he learned how to edit and group photos by subject matter from Michael Wolgensigner, a Swiss commercial photographer favored by the modernist graphic designers of the time. Wolgensigner showed Frank how to make contact prints of 2 1/4” negatives and glue them onto cards, grouped by subject matter.

While Frank was still in Zurich, he made cards with the contact prints of his photographs. Some of his basic themes included animals, architecture, children, farming, and people. Larger themes he approached included: reportage, sports, transportation, work, and Zurich itself.

This training from Wolgensigner to edit and group photos by themes helped build Frank’s discipline– and to work efficiently, pragmatically, and systematically. Although some of his classifications were very basic (children, animals, people), he soon took this to the next level and started thinking about it more conceptually. It helped him what “Looking Inside” says: “[It helped him] recognize subjects and themes that had meaning on him”.

Takeaway point: When you are working on a project (or thinking about starting a project) – try printing out some of your images on small 4×6 prints and group them according to subject matter. You can also do this on Lightroom and other image-editing software, but doing it with physical prints will help you get a more tactile and fluid experience. By grouping your images to subject matter, you will start seeing the reoccurring themes in your work or certain types of images that interest you. Using this as a starting point, you can start thinking more critically and conceptually about your project.

b) What Frank learned about sequencing (adding blank pages)

Another photographer Frank drew early inspiration from was a Swiss photographer named Jakob Tuggener. In one of Tuggener’s books titled: “Fabrik, A Photo Epos of Technology” was comprised up of 72 photographs that showed the destructive power of technology and influence on humans.

Tuggener’s book was divided into 9 parts, each which had a different aspect of the industries and modern technologies. Each photograph was separated by blank pages to function as “hyphens” or “breaks” to provide the viewer to give a chance to reflect on what they just saw. Frank ended up doing the same with “The Americans” – inserting blank pages in-between to also give the viewer a chance to reflect on the previous images. Frank says himself, “To see his photos affirmed the idea that one must ‘be present’.

Therefore by inserting blank pages in-between each photograph forces the viewer of the book to be more of an active viewer, trying to make hidden connections and see the flow of the story, rather than mindlessly flipping through pages. Tuggener was also interested in filmmaking, so you can say that the way that he sequenced his photographs was familiar to that of modernist films, and in admiration of pioneering Soviet Russian film director Sergei Einstein’s principles of montage. Frank also mentioned to Tuggener’s book to being “like cinema”.

Even Alexey Brodovitch, the Russian-born photographer/designer that Frank looked up to, said that he: “Understood that the act of looking at a book was temporal experience, akin to watching a film”.

Takeaway point: When you are sequencing a project or a book, realize the power and importance of blank pages. Don’t simply do it as a stylistic tool, but make it intentional.

c) How Frank learned that sequencing could be a “profound work of art”

The first real example in which Frank sequenced a book (that hugely inspired the sequencing in “The Americans” was from his book: “Black White and Things“. The book was focused on the somber and joyous moments of life. What “Looking In” says about how Frank sequenced the book and built up a sense of rhythm:

“Compounding the sequence’s impact, tone, and meaning, frank for the first time placed most of the photographs opposite blank pages, allowing an almost stately progression of image after image to build up in the reader’s mind. Yet, as readers look through the book, they quickly discover that they must move both forward and backward through it, remembering what they have seen before and knowing what will come next. Thus, form and content become interdependent, and meaning is established as much by the movement between the photographs as by the photographs themselves.”

To emphasize, the meaning Frank created in his book wasn’t just the photographs themselves, but the movement and pauses in-between the pages of the book. Frank also found it important that he didn’t have to explain everything to the viewer so directly:

“Something must be left for the onlooker. He must have something to see. It is not all said for him”.

In terms of what Frank wanted people to feel when looking at his photos? Frank likens it to a poem:

“[I want my viewers to] feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice”.

Takeaway point: When you are putting together a project or book, know that the sequencing of the book is just as important as the images themselves. Be very deliberate on the order you put your images together, and try to create a certain rhythm to it- in which certain photos next to one another can be similar (or dissimilar). Sequencing isn’t something scientific, rather it is something that you feel. Try to sequence your images in which they flow well, and ask your peers for their suggestions on sequencing as well.

d) On pairing images together

Although in Frank’s “The Americans” he only included individual photos per page, he learned the concept of pairing photos together on separate pages from Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein:

“Two film pieces of any kind, placed together, inevitably combine into a new concept, a new quality”.

This is another important concept that you can take-away when creating your own photography book.

Takeaway point: Try to pair images on opposite sides of the pages that may be similar or different- that synthesize into a new concept or have a new meaning. For example, you can have two images on opposite pages that mirror one another or are similar. For example, you have a photograph of a child on the left side of the page, and of a baby animal on the right side of the page.

Or have a photograph of something that is predominantly red on the left side of the page, and another photograph of something red on the right side of the page. You can also do this with polar opposites. For example, if you have a photograph of a rich man on the left side of a page and a photograph of manure on the right side of the page, it will suggest to the viewer your feelings of the rich.

Another example perhaps would be having a photograph of an SUV/Hummer on the left side of the page and of dollar bills on the right side of the page to show how you may feel how wasteful SUV’s/Hummers may be.

2. How Frank processed his film and made initial edits

When Frank was done shooting “The Americans” – he had the monumental task of developing his film, creating contact sheets, making initial edits, and organizing them. “Looking In” writes:

“Throughout the summer and fall of 1956, Frank finished developing the more than 767 rolls of film he had shot for the project, made contact sheets of them, reviewed more than 2,700 frames, and marked those images he thought were of interest. He then embarked on the monumental task of making approximately 1,000 work prints, which he annotated, often with a red grease pencil, with the corresponding number of the roll of film.”

Takeaway point: When making initial edits of a project you are working on, mark anything of which is interest to you. Then you can continue on a more precise edit afterwards.

3. Frank editing his work

When Frank first started developing his film (at his friend’s darkroom) he was ruthless in editing. “Looking In” mentions:

“[Frank] edited them on the spot, unsentimentally cutting off and throwing away those frames he found of no interest. With a quick eye and sure judgment, he discovered that ‘even when the photographs are bad, looking at them is instructive.’”

Not only was Frank able to quickly discard his worst images, but he also used them as a tool to better learn what his good images were. Robert Frank once said this about editing: “What you reject… is just as important“. “Looking In” also said this about Frank’s editing:

“Trying to make sense of this vast accumulation, Frank knew that just as he photographed ‘by process of elimination,’ so too by editing the work prints he could “come into the core” of what he wanted to express.”

Takeaway point: Be ruthless when it comes to your own editing. While you don’t necessarily need to cut up the negatives of your bad photos or delete them, be critical with yourself. Would you want that image to make it into a book? Would you want to see it in an exhibition printed large? Also don’t be frustrated with your rejected images- but learn from them.

4. Initially categorizing his images

Frank also categorized his images accordingly:

“[Frank] also noted those subjects that he had repeatedly explored, such as cars, jukeboxes, and lunch counters, and those that he had only tangentially touched upon, especially religion, the media, the flag, and the look of the new suburban landscape.”

By noting the general categories of subjects that he shot, he was able to get a better understanding of what themes he found interesting about America- as well as other themes he wished to explore more. This included religion, the media, the flag, and the suburban landscape. After his first round of developing and looking at his negatives, he would then go back and make a conscious effort to re-shoot those certain themes. Frank also started to realize that the type of images he was taking started changing. “Looking In” writes:

“[Frank] also recognized that in the last few months not only had his style and approach changed, so too had his intention. No longer striving for poetic effect or even beautiful photographs he now openly sought to express his opinions about what he saw– his anger at the abuse of power, his suspicion of wealth and its privileges, his support for those less fortunate, and most of all, his fears about the kind of culture he saw emerging in the country.”

This goes back to the idea that Frank wasn’t shooting “The Americans” as a transparent documentary project, but rather a project that was personal to him — and full of meaning, anger, and suspicion. This is what Frank said when asked about his thoughts:

“America is an interesting country, but there is a lot that I do not like and that I would never accept. I am also trying to show this through my photos”.

Therefore his images weren’t just about creating aesthetically pleasing images. Rather, he wanted to bring attention to injustices he saw through his photos.

Takeaway point: When you are working on a project, by categorizing your images and tracking them – you can see how your own intention, style, and approach can change and evolve. When you see your work evolving into something else than you originally intended, don’t try to force it. Go with the flow and let your work take a life of its own.

5. Organizing his prints

When Frank made his nearly 1,000 work prints, he did the following to organize his prints. “Looking In” shares:

“Out of this chaos [Frank] began to construct some order. He spread the work prints out on tables and the floor of his apartment and thumbtacked, even stapled them to its walls.

By tacking and stapling the images on his apartment, he would live with the photographs – and get a better sense of what he felt were the strongest images, and how he should sequence them. “Looking In” elaborates on the themes that Frank identified:

“Following the training he had received in Zurich from Michael Wolgensigner, he grouped them at first by themes: cars, race, religion, politics, and the media were the major components, but he also arranged them by depictions of the way Americans live, work, eat, and play, as well as by more minor subjects that had caught his attention — such as cemeteries, jukeboxes, and lunch counters. And he devoted one group to images of his family.”

Frank would then constantly move around and re-pin his photos in different parts of his walls and houses:

“As the boundaries between the groups were porous and the divisions fluid, he frequently moved prints around, often ripping them off the walls only to thumbtack them next to a new neighbor or set them aside entirely in a box. Sometimes he put red circular marks on those photographs he considered strongest; occasionally he marked them to indicate how they should be cropped.”

Also through this process, Frank decided which photos and themes he should eliminate:

“In the process, [Frank] entirely eliminated some subjects he had thought he might explore, such as the suburban landscape people trapped by the detritus of consumer culture, and any literal allusion to the immigrant experience. He later estimated that he spent 3 to 4 months doing this evaluation and editing– it was, he told a group of students, “‘the biggest job on that book.’”

Therefore you could see that in order to create “The Americans” – Frank took editing very seriously. Not only did he edit by intuition, but he also did it analytically by exploring certain themes. Another important note to make is how he decided to get rid of some themes in the book, such as the suburban landscape, consumer culture, and the immigrant experience. By cutting out these other themes, he was able to focus on the central themes in his book such as race, religion, and the overwhelming sense of alienation.

Takeaway point: When you are editing your own work, try the same technique. Although we have ways to do it digitally (Lightroom, Aperture, etc) there is great merit in doing it via the analogue approach. Print our small 4×6’s and spread them out on the ground, tack them to your walls, and move them around. There is something amazing about this tactile approach which is hard to describe – which can help you get a better final edit/sequence of your work.

6. Creating the structure of “The Americans”

Upon editing his work, Frank then focused on the sequence and the structure of the book:

“Next, he worked on the sequence itself. Laying out some of the work prints on the floor or tables and pinning others to the walls, he slowly devised a structure. Like his own “Black white and things”, Evans’ “American photographs”, and Tuggener’s “Fabrik”, his book would be divided into four chapters, each separated by blank pages, most opening with a photograph of a flag.

One thing that Frank also did which was radical at the time was to crop his images. Sometimes radically, and at other times less radically:

By spring 1957, Frank had cut down his one thousand work prints to approximately one hundred and made new prints, which he more carefully considered the cropping. Sometimes he used the full negative, as in Trolley- New Orleans, but more often he presented only a portion of it.”

“Looking In” shares some of the figures Frank eliminated through his cropping:

“[Frank] eliminated a distracting figure on the far right in City Fathers – Hoboken, New Jersey; emphasized the cross like forms behind the conventioneer, in Political Rally – Chicago, and the evangelist in Jehovah’s Witness- Los Angeles, tightened the relationship between the campaign posters and the bumper pool table in Luncheonette – Butte, Montana; and focused more closely on the lonely young woman in Elevator – Miami Beach and on the scheming politicians in Convention hall – Chicago.

Some of Frank’s crops were radical:

“He even extracted two vertical prints, Hotel Lobby – Miami and Movie Premiere – Hollywood from horizontal negatives.”

Touching upon sequencing again in the book and creating a maquette (a dummy book):

“Working quickly and intuitively, with no preconceived ideas about the subject of each chapter, he sequenced the book, once again laying the photographs out on tables and the floor and pinning them to the walls. As he worked, he established only one rule: if two selected photographs came from the same contact sheet, one would follow the other in the sequence. And finally he made a maquette, 8 3/8 by 9 1/2 inches, with photostats of ninety two of the selected images.”

Takeaway point: Although personally I am not a huge fan of cropping, you can see that Frank cropped many of his photos – some of them quite radically (turning horizontal shots into vertical shots). Therefore if you want to make a photograph more powerful, have more focus onto a single subject, and get rid of distractions, crop your shots.

7. The initial maquette (dummy book) of “The Americans”

The maquette (initial dummy book) of “The Americans” showed many things about what Frank tried to express through the sequencing. “Looking In” shares:

“The maquette indicates that, as he had begun to do in ‘Black White and Things [one of his previous books],’ in his book on america, meaning would be garnered through a deliberate progression of images that did not rely on obvious side by side comparisons but instead engaged readers in a much more active manner, asking them to recall what they had seen on previous pages and reflect on their relationship to what they currently saw.

Many other books published during Frank’s time often showed two photos side-by-side on opposite sides of the page– sometimes with similar subject matter and sometimes totally opposite. Rather, Frank deliberately had only one photograph per two-page spread, to force the viewer to recall the images they saw before and think about the meaning. “Looking In” continues:

“While demanding more of his readers and enticing them to join him in a voyage of discovery, Frank also more fully engaged them intellectually, emotionally and even viscerally.”

To force the reader to make connections between the breaks or pauses in a book challenged them to be much more active in digesting and understanding the book. Rather than being passive readers, they would be active participants.

Takeaway point: Depending on what you want your project to do for the reader, consider either pairing similar images (or different images) side-by-side on the same spread. Or insert breaks in-between to help the reader become a much more active participant in reading your project/book.

8. The flow of images

When Frank sequenced the book, he didn’t want to have a book of stand-alone images. He didn’t see any of his photos as individual images, but part of a larger collection. When asked about how he sequenced the book, Frank said in an interview:

“I tried to not just have one picture thrown in alone, isolated as a picture. That’s what I tried to do. I think it often sort of succeeds.”

Not only did he want to create meaning through associations and relationships, but he also wanted to create a movement through his photos. Frank continues:

“I wanted to create some kind of rhythm… I’m not sure now whether I wanted to have first pictures that didn’t move and then move movement in the pictures later on in the next few.”

During his lifetime Frank was very fascinated with theater and film (he pursued it actively after completing “The Americans”). Very much so he tried to sequence the book like a moving picture – having the static photos move with energy, vigor, and life.

Takeaway point: Don’t think of your photography project or book as a book of single images, but rather a collective full of images that flow well and have meaning stacked on one another.

The Critical Response of Frank’s “The Americans”

Although Frank’s “The Americans” is now revered as one of the most important photo-books ever made in the history of photography, it was very controversial when it first came out – and Frank encountered considerable criticism.

For example critics described the book to be “a slashing and bitter attack on some U.S. institutions,” “a wart-covered picture of America,” and a “disturbing” portrayal of “the Ugly American.”

Frank was also personally accused of being a “joyless man who hates the country of his adoption” and “a liar perversely basking in the kind of world and the kind of misery he is perpetually seeking and persistently creating.”

Some more criticisms that he received was that he was a “poor essayist with no convincing storyteller at all” and that his ulterior intent was to “…let his pictures be used to spread hatred among nations.”

More criticism that Frank received that the photographs themselves had “…no sociological comment. No real reportial function… being merely neurotic, and to some degree dishonest”.

Frank’s title of “The Americans” also received considerable attacks, with his detractors saying that it was “Utterly misleading! A degradation of a nation!” It is important to note that influential works generally face lots of opposition and criticism.

Takeaway point: Even the best photography books and projects in history have received considerable criticism. Know that when you create a book, project, or a body of work – don’t expect it to be praised by everyone (no matter how great it is). If anything, take criticism as a sign that your work is evoking a reaction (which may in-fact be a good thing).

On Originality (when applying for the Guggenheim)

One of the worst pieces of advice I often hear photographers telling others is: “Don’t work on that project, it has already been done before”. When it comes to Robert Frank’s “The Americans”, photographers see it as a very original and groundbreaking piece of work. However in reality, when Frank decided to embark on his project, America had already been photographed quite extensively by renowned photographers such as Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Evans creating his pivotal project on America was actually the one who encouraged the young Frank to apply for a Guggenheim to embark on his project. “Looking In” writes:

“A few months before “The Family of Man” exhibition opened, Evans as a confidential advisor to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation encouraged Frank to apply for a fellowship. Frank’s intended project– to photograph throughout the United States– was neither unexpected nor novel.”

Also from the text, about the other famous photographers who embarked on photographing America:

“Many American and European photographer before him — from Cartier-Bresson to Frank’s friend Elliott Erwitt, to name only two of the most recent– had photographed their travels throughout the United States.”

Takeaway point: When you are working on a project and people tell you not to work on the project because “it has been done before” — take their advice with a pinch of salt. Of course we want to create original pieces of work and not copy photographers who have already done strong bodies of work on a certain subject or topic.

However what we can take away from Frank’s example is that he still embarked on “The Americans” even though the topic had been covered thoroughly. If you want to embark on your own project that has already been “done before” — add your own style, originality, and flair to it. As photography has been around for over a century now, most subject matters have been thoroughly covered by photographers. There are very few subjects, which are “original”. But know that because you are the one taking the photos, they will always be original in that regard.

Frank’s Guggenheim Fellowship Application

When Frank applied to photograph The Americans he needed financial support to go on his 2-year long journey throughout America. To finance his trip, his mentor Walker Evans encouraged Frank to apply for the Guggenheim fellowship. With considerable amount of help from Evans (on writing the proposal), he submitted his proposal, which awarded him $3,600 to loop around America from 1955-1956. The proposal of the grant in-full is shown below:

Part 1: Frank’s brief summary of the proposal

To photograph freely throughout the United States, using the miniature camera exclusively. The making of a broad, voluminous picture record of things American, past and present. This project is essentially the visual study of a civilization and will include caption notes; but it is only partly documentary in nature: one of its aims is more artistic than the word documentary implies.

Part 2: The full statement of intent

I am applying for a Fellowship with a very simple intention: I wish to continue, develop and widen the kind of work I already do, and have been doing for some ten years, and apply it to the American nation in general. I am submitting work that will be seen to be documentation — most broadly speaking. Work of this kind is, I believe, to be found carrying its own visual impact without much work explanation. The project I have in mind is one that will shape itself as it proceeds, and is essentially elastic.

The material is there: the practice will be in the photographer’s hand, the vision in his mind. One says this with some embarrassment but one cannot do less than claim vision if one is to ask for consideration. “The photographing of America” is a large order — read at all literally, the phrase would be an absurdity. What I have in mind, then, is observation and record of what one naturalized American finds to see in the United States that signifies the kind of civilization born here and spreading elsewhere.

Incidentally, it is fair to assume that when an observant American travels abroad his eye will see freshly; and that the reverse may be true when a European eye looks at the United States. I speak of the things that are there, anywhere and everywhere — easily found, not easily selected and interpreted. A small catalog comes to the mind’s eye: a town at night, a parking lot, a supermarket, a highway, the man who owns three cars and the man who owns none, the farmer and his children, a new house and a warped clapboard house, the dictation of taste, the dream of grandeur, advertising, neon lights, the faces of the leaders and the faces of the followers, gas tanks and post offices and backyards.

The uses of my project would be sociological, historical and aesthetic. My total production will be voluminous, as is usually the case when the photographer works with miniature film. I intend to classify and annotate my work on the spot, as I proceed. Ultimately the file I shall make should be deposited in a collection such as the one in the Library of Congress. A more immediate use I have in mind is both book and magazine publication.

Quotes by Frank on “The Americans”

What I learned from “Looking In” is that although photographers have analyzed Frank’s “The Americans” to death, teachers, and academics- Frank himself said very little about his project. Some quotes that didn’t necessarily fit into the rest of the article I have compiled here:

1. On why he used black and white for “The Americans”

“Black and white is the vision of Hope and despair. That is what I want in my photographs.”

2. What he wanted to show through his photographs:

“Somber people and black events quiet things and peaceful places and the things people have come in contact with this, i try to show in my photographs”

3. On why he photographs:

“Above all, I know that a life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference.”

Getting “The Americans” published

Many of us know how difficult a task it is to get our work published in a book. Even during Frank’s time, it was quite difficult. In an interview with Robert Delpire (the original publisher of “The Americans”) by Michel Frizot in Feb 2008, we discover how Frank first approached Delpire to get his work published in a book:

Michel Frizot: How did the publication of Les Americains come about?

Robert Delpire: One late day in summer 1954, I think, Frank was in Paris and he told me, “I want to do a big project on America, and I’d like to apply for a Guggenheim grant. You would need to sign a paper for me, agreeing to publish a book with my photographs. I think that would allow me to get the grant. I signed the paper, he got the grant.

He came back about three years later and showed me the photographs. He had his own idea for the book, but he did not have a mock-up prepared. He wanted a single photograph per double page. He said, “I don’t like combining photos.” I immediately subscribed to that point of view, and we did the mock-up in one afternoon, at my place, lining up the photographs on the floor.

There are some photographers who do not know how to choose their photos, but he did. And there was no problem in terms of the selection. As for the sequence, we did it just like that, intuitively. The number of photographs was not predetermined, it just happened, with us choosing one by one. A hundred and seventy-four pages, that’s not even a multiple of eight [referring to the minimum number of pages in a folded press signature].

Getting Jack Kerouac to write the introduction

For the introduction of his book, Frank was lucky enough to get the renowned Jack Kerouac (author of “On the Road”) to write it for him. How did Frank do it? To start off, when Frank first heard of the New York Times review of “On the Road”, he met Jack Kerouac at a party where he asked him to write the introduction. Joyce Johnson, who was Kerouac’s girlfriend at the time, shared her recollection of the event:

Robert Frank walked in with a couple of boxes of his work. For several years he’d been going around the country taking photos for a book he planned to call The Americans. He was hoping to convince Jack to write an introduction. He asked me if I’d like to look at the pictures. The first one I saw was of a road somewhere out west– blacktop gleaming under headlights with a white stripe down the middle that went on and toward an outlying darkness. Jack’s road! I thought immediately.”

From that moment Jack Kerouac agreed and wrote one of the finest and jazzy introductions that has ever been written for a book. You can read Kerouac’s full introduction here.

Contact sheets of interest

1. The progression of how he got his famous cover photo for “The Americans”

This contact sheet is quite interesting. Frank took a total of 5 photos of the scene. He first saw the American flag in front of a building, and saw figures peering out. However the windows obscured the people.

Upon shooting some other frames, he found another scene of two women looking out into the political rally, and just made one exposure- which became the famous cover photo of “The Americans”.

Takeaway point: If you see an interesting scene, keep your eye on the lookout. At first the scene may not work, but you might find similar scenes or the scene evolving over time. Always be ready.

2. Political rally

During a political rally, Frank saw a man campaigning- yelling and proclaiming himself vigorously, with his arms outstretched. You see he took several frames of him, and then was able to capture “the decisive moment” in which he has his hands fully-extended.

Takeaway point: Don’t quit shooting until you captured “the decisive moment”

3. Progression of his “elevator girl” shot

Frank’s famous image of the “elevator girl” who looks quite bored, pressing the doors open for the people to enter/exit wasn’t just a single shot. You can see how he shot 15 exposures of the same scene, even with a few shots of the girl posing for him at the end.

Takeaway point: if you see an interesting scene which you think has potential, don’t just snap a single exposure and move on. Wait, and work the scene.

4. St. Francis statue

In one of his most poignant photos in “The Americans”, Frank photographed a statue of St. Francis. Fascinating to note that his original pick of the scene was different from what was the final image.

Takeaway point: Your first initial gut instinct for choosing a photo may change over time. Also if you see an interesting scene, take it from different angles and different exposures (especially if it is a statue or something that doesn’t move).

Conclusion

Robert Frank’s “The Americans” was one of the most influential photography books created of all time. However remember that it is interesting to note that at the time it wasn’t an original project at all. Walker Evans and Henri Cartier-Bresson already covered America, but Frank went ahead, followed his own gut, and created a project that broke all sort of standards. Instead of being straightforward “documentary”, Frank expressed his own alienated feelings of America. Dark, gloomy, and unjust.

In going against the prevailing transparent-styled photography of the time, he had a ton of critics of his work that ostracized him from every angle. However his work has now inspired countless photographers and has left its marks for generations to come. Although I doubt that Frank would call himself a “street photographer” — his way of working was very similar. He traveled across the country, took most of his photos candidly and worked with speed, elegance, and a sense of fluidity.

As street photographers we can learn so much from Frank — in terms of his imagery, how he put together his book, and also how he went against conventions. This article on Frank isn’t comprehensive and I’m sure there are many holes that I failed to fill. However I still hope that you took away something meaningful from this article.

Although it took me several months to put this post together (in terms of the research, the writing, formatting, and getting the images) and I’m sure there are some mistakes, spelling errors, or grammatical errors I have made. Please make some suggestions in the comments below.

Further reading

1. “The Americans” by Robert Frank

Of course if you want to learn more about “The Americans” it is imperative that you pick up a paperbound copy of your own.

2. “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans” by Steidl

This behemoth of a book is what I used to conduct the research for this article. It is much more thorough than my post, has examples of mock layouts of the book that Frank created, his work prints, as well as his contact sheets. This is a book that you must have in your library if you are serious about learning more about photography.

3. “By the Glow of the Jukebox: The Americans List” by Jason Eskenazi

Jason Eskenazi is a talented photographer who embarked on a 10-year odyssey through the old soviet union and published his book: “Wonderland: A Fairytale of the Soviet Monolith” (see the interview with Charlie Kirk on my blog here).

For about 10 months in the past, he was also a guard at the MET Museum in New York. Believe it or not, he was the guard for the “Looking In“ exhibition for Robert Frank’s “The Americans”. He then asked many renowned photographers what was their favorite image and why. He then compiled 276 photographers answers in the unique book. Definitely a must-have accompaniment for “The Americans”.

You can see a preview of the book here. Order a copy online here.

How has Robert Frank’s work influenced you? Share your thoughts about “The Americans” below – and also please let me know of any typos, grammatical mistakes, or corrections in the comments below!