I’m not 100% sure how I stumbled upon the book: “Minutes to Midnight” by Trent Parke. But when I did— I was blown away by Trent Parke’s incredible story-telling, visuals, and vision. It inspired me to write my first article on him: 12 Lessons Trent Parke Has Taught Me About Street Photography.

Steidl has recently re-published “Minutes to Midnight” — and it has been a massive hit. It is hard to find copies that aren’t sold out, you can currently get some more pre-orders on Amazon.

For the Steidl re-print, there has been a slight change to some of the images, formatting, and printing (all in a positive way). I currently have my copy of “Minutes to Midnight” in my street photography library— and it is one of the most precious black and white books I own.

I wanted to write this article sharing my thoughts on the book, why I think it is a great body of work, and I hope you find this article useful.

How Trent Parke Created “Minutes to Midnight”

When it came to work on “Minutes to Midnight“, Parke saved up a lot of money (and felt a lot of personal images) before creating the body of work:

“I’d been saving up for five years to make a long road trip around Australia. I sensed somehow something wasn’t quite right out there and I wanted to go see for myself. In the end it was an article I read in a newspaper that finally got me going. A report that said that more than half of Australians felt the country had lost its innocence. It struck a chord. Certainly it did seem a very different place from the Australia I had grown up in 20 years earlier.”

Parke also shares his personal thoughts on Australia, and the social inequalities and injustices:

“Australia is a hard country with the droughts and the firestorms and the poverty. And while there is a kind of freedom to it, there is also a stifling sense of inevitability. People in the outback live by standards that city people would never understand. But then you come to realize that it’s just the way people survive and have done for so long. There’s no malice in it – it’s just instinct. It’s just the way it is…”

Parke shares some big themes he worked on in “Minutes to Midnight”:

“But even with work like Minutes to Midnight that’s so much about regional and remote Australia there’s lots of things that could relate to the wider world. The bigger picture things: terrorism, racism, poverty, natural disasters and the struggle to survive. So I found I was using this symbolism to tell a much bigger, epic story of the world through pictures made specifically in Australia. I think people can relate to this work in many ways.”

Parke also shares some of his outside influences which informs his darker, dreamy vision:

“I’ve been influenced by all sorts of things. Music videos have been great … There is this Icelandic group Sigur Rós – their music is just very sad and melodramatic. Nine Inch Nails and Radiohead and those sorts of bands and their cutting-edge film clips have influenced me. They have this kind of dark, dreamy quality and I suppose that was what I was trying to evoke. But, to be honest, I don’t really realize all this when I am shooting because the stuff inside me and the stuff outside me kind of flows through me into the pictures … Most of the time I’m in another world [laughs].”

Trent Parke on “Minutes to Midnight”

To start off, Trent Parke shares some of his thoughts on “Minutes to Midnight” — and the meaning behind it for him:

“This body of work is about the emotion of the time that we live in—it is not a physical sense but an emotional sense and the subconscious and the thought of what might happen. It is a document but a fiction as well.”

“So Minutes to Midnight is an apocalyptic book, but they’re real documents as real events—real moments in time that have happened.”

When it came to putting together “Minutes to Midnight” — Parke treated it almost like a film:

“I looked at Minutes to Midnight as the way I wanted to create it was almost as a film clip. I find it amazing to see how much imagery you can pack into a 3-minute song, and how effective that can be.”

Furthermore, Parke shares the fictitious aspect of the project:

“Minutes to Midnight was that sort of style of work – I was trying to get images that had no real connection and then making a fictional personal story of them, I suppose. They were like fragments of dreams and nightmares and all this imagery that sort of somehow syncs to the back of your mind and gets drenched, or pulled up at certain times.”

A lot of what inspired “Minutes to Midnight” was from this state of fear that pervaded Australia, especially during all of the terrorist attacks during and after September 11th. Parke wanted to capture this raw emotion:

“I find it incredible in Australia after all the terrorism, all the major terrorism attacks like September 11th, there was this barrage in the press everyday for the next few years—everyday about the imminent attack that will happen at some stage to Australia, or to the country you’re living in—there was this sense that the politicians were bringing this: ‘It’s going to happen, its only a matter of time’ – but it depends where you come from and what you’ve been influenced with growing up. [Your life experiences will affect] the reaction you will have to certain imagery.”

When it comes to making images, Parke sees the potential and metaphor of images (rather than the images themselves). For example in one of the photos in the book:

“Things that i’ll see, i’ll see completely different in a picture, and when I’m photographing—I’m not thinking of a car racing across a desert, I’m thinking a wave rolling…”

Parke also wants the photos he makes to be open-to-interpretation (depending on who the viewer is):

“It just depends what’s happened in your life to bring these sorts of images and what they conjure up and what they mean to a specific person.”

“It’s important that people react to the images from their own perspective of where they’re come in life, that certain images will create a different reaction from other images because of what they’ve experienced in their lifetime.”

So where does the imagery and vision Parke has for his images come from? He shares his childhood:

“That comes from the depths of my imagination and where I’ve come from a child growing up, and what’s been influencing me and my life.”

One of the most intense photos (near the end of the book) is the birth of his son, Jem. He shares the intense and personal experience:

“When I was photographing the birth of my son Jem I couldn’t remember for quite a while the actual moment of birth. It all went blank. I don’t remember anything, I just went into automatic. There was poor light and I found it difficult to focus the camera. It was only after I looked at the roll of processed film that it all started to flood into my memory – what had actually happened. I had gone blank for those 10 to 15 minutes; I was so in the zone making pictures. I have never been so intensely scared as when I processed that roll of film because I knew something had happened and I didn’t want to have missed it.”

Trent Parke on Creating Bodies of Work

I think Trent Parke is a great photographer to study when it comes to creating bodies of work. He is incredibly obsessive with his work, and has a laser-like focus to create books that span many years. He shares the importance of sequencing and storytelling:

“Single photographs are obviously what you try to get to, but for me—the real art and the real skill I do is taking 45-50 images and sequencing them in a way that they tell a story—I’m a storyteller that’s what I do, I love storytelling. So I take documentary photographs, but then I arrange them in a way that turns them into something else—another sort of story or another idea.”

The sense of mystery and chance is also what drives his work:

“For me its all about chance, coincidence, mistakes—I love mistakes- and photography allows me, it is still that moment when I pull those films out of the tank and hold them up and look at those images, and you just never know. If I know what’s on those images—I’m not interested in all those processing. I’ve got thousands of rolls that are just shoved aside because there was no mystery, no excitement—no extra element that had come into the image. I know that, so they just pushed aside. It’s the ones when you pull them out and go, look at that– ‘life, chance’—all these elements come together for a split second and create it—and the process of chemicals on film all of those ideas, and then all of a sudden, something is unique is there, that presents itself.”

What makes a great photo? Sometimes it is the small details:

“A lot of the time, I will also see something on the negative and say, there’s a tiny little thing—wow how did that happen? And then ill go over and over and try to re-create that in a bigger picture, or until I’ve exhausted the possibility of that small little discovery. It is all about discovery for me in making those things that change your perception of where you’re going with the next body of work.”

For example, he brings up one of his most famous images in “Minutes to Midnight”:

“I saw this particular part of this image on this negative—and I went back everyday for 3 months until I got this particular picture, until Id exhausted every possible option but, I got the big picture that I was after that id never see being replicated again, and it came down to a moment with many sorts of facets and things going on in the image that all come together for that one split second, and gone—forever.”

Working with Steidl

In an interview, Parke shares his experience publishing “Minutes to Midnight” (as well as “The Christmas Tree Bucket“) with the famous Gerhard Steidl.

One of the most difficult parts was the wait:

“The experience was definitely an interesting one and at times a little frustrating. The frustrating part was the wait. Gerhard had Minutes to Midnight for about six years before it was eventually published. (This probably added to the reason it sold out in a few days.) The first of three trips to Germany (Gerhard’s formula) to make the books was crazy. I made the long journey from OZ, waited for three days in the Largerfeld apartment beside the printing press, and then with about five minutes to go before I was to jump a two hour train ride back to the airport and then a flight back to Australia, I was summoned to the library where we made plans for the books.

‘What paper do you want?’ he asked.

‘That one’ I said. (The most beautiful of course.)

‘Done!’ He said.

‘Soft cover? Hard cover? Slip case? What do you want?’

‘Hardcover. No slip case.’

‘Done!’ he said.

‘Tri-tone printing?’

‘Yes.’

‘Done!’ he said.

Parke was stunned how quick the process was (but ironically long):

And that was it, same for both books, all the way to Germany for about three minutes work. He then put me in one of his cars with a driver and said, ‘There you go. Hop,Hop,Hop,back to Australia.’ And the driver drove me at break neck speed to the airport to make my flight in time. (Man they drive fast !!!!!!!) The second visit, a couple of years later, was similar. I waited for a week to lay out the books only to find Gerhard had flown to Paris urgently. He then instructed his staff to cancel my flights and stay another ten days – always a waiting game. But the one benefit of all this waiting is the Steidl library. I could of waited in there a lifetime if need be.

Trent Parke remarks on the quality and standards that Steidl has:

“The amazing thing about Gerhard is that he spares no expense. He will make the book exactly how the artist wants it, and you know the printing is going to be the best. He is incredibly quick to grasp and concept a project. He really is a genius. We have already made plans for Black Rose while on press for Minutes to Midnight and Christmas Tree Bucket and he will make the entire Black Rose set (Though this time he assures me it will not take as long!)”

Minutes to Midnight: The Photos

I will share some of my favorite photos from the book, and share some of my thoughts on the images– and why I love them so much.

This is the first image in Minutes to Midnight– and I love it as a leading image. It is dark, mysterious, and almost looks like the moon. I love the spherical shape juxtaposed against the pitch black, and the ominous feeling of the flies on the light sphere.

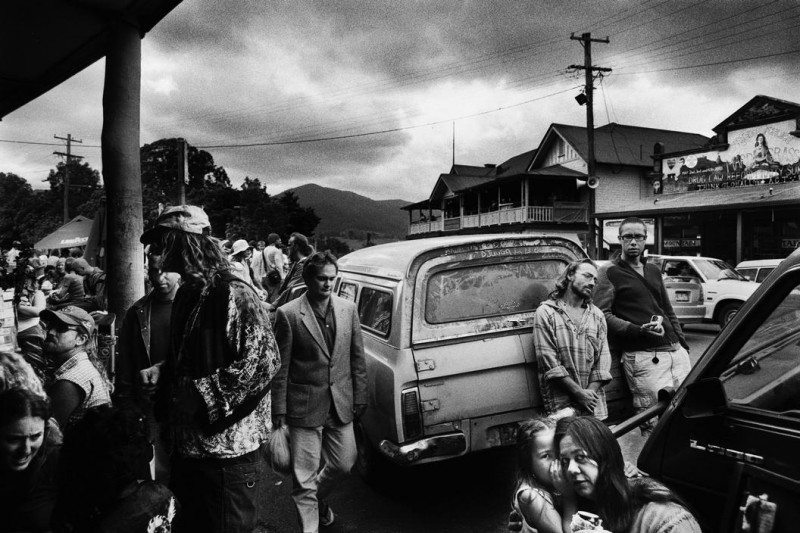

The beginning of the book Parke sets the stage for the ominous journey which is “Minutes to Midnight.” You see hordes of people (from all walks of life)– bunched together in a chaotic sort of manner:

The first strong single image that breaks the “scene-setting” is a minimalist photo of a man about to jump into a pool of water. Parke captured him mid-air, and when I look at this image– I nearly hold my breath. I love the grain and texture in the sky, and the stark blacks in the bottom of the frame:

Parke also includes lots of photos of nature and animals in his photos, like this dragonfly below. The metaphor I think Parke is trying to say here is the feeling of being trapped. However the image is an elegant one– with lots of deep blacks, and beautiful light and contrast on the spiderweb and dragonfly:

Skipping ahead– you see people at a beach looking out at a dark and brooding sky– it is as if something dark is going to happen:

Following up on this image, you see a photo of a dead cockatoo (roadkill)– a beautiful and elegant bird juxtaposed against a diagonal line going through the dark pavement. It is another warning from Parke that dark things are to come.

I then am suddenly shocked by seeing the next image– a little girl in a field looking straight at me. It is a bit unsettling in the sense that all the previous photos made me feel like an outside voyeur looking in– and now someone is aware of me, looking into my soul:

Suddenly the camera pulls back (from being really zoomed in, to really far away)– giving you an entire cityscape of Sydney. To me, you almost see the face of a demon in the sky:

At this point forward, you get a barrage of very strong single-images from Parke.

You get his famous “bus” photo — that looks like people burned into a white tapestry, scrolled across the streets of Sydney. Almost reminds me of the ashes of victims of Hiroshima that were burned into buildings after the dropping of the atom bomb:

The next image is also an iconic one: of a man stepping into the light, which almost makes him look like an alien. As a side note, to achieve this effect– Parke exposed for the shadows, which over-exposed the man stepping into the light:

Then you have a photo that is an ode to Robert Frank’s “The Americans” — of a car cover (all white juxtaposed against all black– similar to the previous photo):

Skipping ahead some images– you then have a boy staring into an empty screen that is glowing white. It is almost like the television is signaling some sort of mind-control over the raptured boy. The image reminds me of photos of televisions from Lee Friedlander:

The image then once again pulls back– and you suddenly have an aerial view of what looks like wave. But upon closer inspection– it is a rally car spewing dust behind it. It is a simple, powerful, yet elegant image:

In “Minutes to Midnight” Trent Parke also experimented a lot with flash, infa-red film, and more to create his dystopic vision of Australia. You suddenly have a photo of a possum leaping across a trip (apparently Parke waited a long time for this image). The image catches you off balance:

You then get a series of images in the book that sequence beautifully– more fear, anxiety, and death:

You then get three images– which show death and burials, with the humans sandwiched in the middle:

Then there is a self-portrait of Parke himself– who almost looks like a Jesus figure coming to bring salvation:

You have the rain in the next photo perhaps as a metaphor of “cleansing”:

Hope:

Birth (a photo of his wife Narelle Autio pregnant — who is also a phenomenal photographer). The image is very surreal– almost like a pregnant virgin Mary underwater:

A beautiful next image of some jellyfish:

Skip some images– and you have the epic climax of his son, Jem being born (feels symbolif of a baby Jesus):

Conclusion

I think one of the most beautiful part of photography books are that they aren’t just images. A photography book is a journey– that takes you inside the mind of a photographer, while also giving yourself the opportunity to make up your own story. A photography book is open to interpretation, engaging, and an experience.

I think what ultimately makes “Minutes to Midnight” so powerful is the raw emotion, soul, and energy in the images and narrative. Parke really puts his heart and soul into the imagery, and his fanatical level of perfectionism has helped create one of the strongest bodies of work to be made in the last decade.

Remember, whenever you’re not feeling inspired in your photography– buy books, not gear. And I think all of us can aspire to make a photography book for ourselves. It takes a lot of energy, time, and money– but I truly do feel a book is the ultimate form of expression for a photographer.

Videos on Trent Parke

Interviews:

More Work by Trent Parke:

Books by Trent Parke

Below are the books I highly recommend everyone to get from Trent Parke (two both strong bodies of work, published by Steidl). It is an investment you won’t regret.

1. “Minutes to Midnight“

2. “The Christmas Tree Bucket“

Other Street Photography Book Reviews

Below are some other street photography book reviews I have wrote, which I highly recommend:

- Street Photography Book Review: “The Last Resort” by Martin Parr

- Street Photography Book Review: “Gypsies” by Josef Koudelka

- Street Photography Book Review: “Capitolio” by Christopher Anderson

New Street Photography Books

Below are some new street photography books I highly recommend everyone to invest in:

- “The Decisive Moment“: Henri Cartier-Bresson

- “Exiles“: Josef Koudelka