I recommend reading this article by saving it to Pocket, Instapaper. All images in this article are copyrighted by Josef Koudelka and Magnum Photos.

“Exiles” by Josef Koudelka is one of the must-buy books of this year. Previously (before this re-print by aperture) the book would sell second-hand for around $300. I personally couldn’t afford a copy — and when I heard this edition (the last and final) was coming out, I jumped on it like a fat kid on cupcakes.

Before writing this book review, I re-read the book several times, read a lot of interviews by Josef Koudelka– and reflected on the book (and the life and photography of Koudelka).

To sum up, I believe that Josef Koudelka is one of the best photographers who has ever lived (and is still living today) — and his philosophies on life and photography has deeply inspired and moved me. In-fact, I have already written several articles on him:

- 10 Lessons Josef Koudelka Has Taught Me About Street Photography

- 7 Lessons Josef Koudelka Has Taught Me About Photography and Life

- 8 Rare Insights From an Interview with Josef Koudelka at Look3

- Street Photography Book Review: “Gypsies” by Josef Koudelka

I have also discovered that there is a huge shortage of photography book reviews on the internet (although there are tons of gear reviews online).

I just came back from Dubai a few days ago, and am still massively jet-lagged (there is an exact 12-hour time difference between Dubai and Berkeley in California) but will try to start writing more photography book reviews. I have a sizeable number of photography books in my library which I cherish– and I hope to share some of the lessons, my personal thoughts, and reflections on these books.

So with no further ado– let’s delve into Koudelka’s “Exiles“.

“Exiles” by Koudelka

To give a little bit of background of “Exiles” — it was first published in 1988 and included images (mostly) in Europe from his 20-year-exile from Czechoslovakia, starting in 1970 (after leaving the Soviet-led invasion of Prague).

This is what Cornell Capa once wrote about Exiles:

“Koudelka’s unsentimental, stark, brooding, intensely human imagery reflect his own spirit, the very essence of an exile who is at home wherever his wandering body finds haven in the night…”

Personally I think “Exiles” is such an incredible book because it gives you a more personal look into the life, trials, and tribulations of Koudelka himself. I see “Exiles” as a very personal photography journal/memoir of the travel, life, and journeys of Josef Koudelka. His other great body of work (“Gypsies”) is more anthropological and sociological in nature– examining outwards towards the life and communities of the Roma people (politically correct phrase for “Gypsies”).

New Edition of “Exiles”

This new edition is published in 2014, and includes 10 new images. I believe this is the third re-print of “Exiles” (and final, said by Koudelka). Every edition changed the sequencing of images (and edit) slightly. I don’t own the other versions of Exiles so I can’t speak whether this edition is any “better” or “worse” than the others– but it is still a photography book that every passionate street photographer should own in his/her own library.

Here are the “stats” of the book:

- Hardcover: 180 pages

- Publisher: Aperture; 3 edition (October 31, 2014)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1597112690

- ISBN-13: 978-1597112697

- Product Dimensions: 1 x 11.8 x 10.8 inches

- Shipping Weight: 3.8 pounds

The new edition includes a total of 75 images, ranging from the years (1968-1994)– images over a 26 year span! It makes me realize that for truly great work– it takes a long time.

Introduction essay on “Exiles”

In the introduction of “Exiles” — there is a superb essay by Czeslaw Milosz who writes about exile in general (which he originally also wrote in 1988). He tries to go into the psychology of what it means to be an exile– and through reading this essay, us (the readers) can get a better sense of where the images of “Exiles” are coming from.

Lessons I learned from “Exiles” on street photography (and life)

After the essay by Czeslaw Milosz we get an even better page where Robert Delpire and Josef Koudelka share some of their ideas on “Exiles” — which was drawn from various publications and conversations with Josef Koudelka and Robert Delpire. I extracted the most (personally) interesting bits below:

1. Building your life from scratch

“Being an exile insists that you must build your life from scratch. You are given this opportunity. When I left Czechoslovakia, I was discovering the world around me. Of course, one is still drawn to certain people.” – Josef Koudelka

Josef Koudelka is endlessly fascinated by people– which has lead him to constantly traveling the world, meeting new people, and documenting individuals all around him (especially when he took 10+ years to document the Roma people he met in “Gypsies”).

When Koudelka was exiled from Czechoslovakia– he had no other option but to travel. He felt stateless– without a home. But at the same time, I think that being exiled was the best thing that ever happened to him. It gave him the chance to “build his life from scratch” — and he was given the opportunity to travel (without anything holding him back).

Traveling allowed Koudelka to explore and discover the world around him — and pursue his life’s path: photography.

Takeaway point:

Simply ditching your family and leaving everything behind for photography isn’t for everybody. But anytime some terrible shit happens in your life (breakup with your partner, moving to a new country and leaving behind friends and family, or losing a job)– can be a great chance and opportunity for you to “rebuild your life from scratch” — and photography is a beautiful way to document this journey.

2. On the freedom of traveling

“Without freedom to travel I wouldn’t have been able to make many of these photographs. Nevertheless, when I lived in Czechoslovakia, freedom for me meant mainly being able to do what I wanted and, within our limited freedom, I was able to find space for my work. I didn’t need to go somewhere far away to take photographs. I knew that if I was worth anything I had to prove it in my country. When I left, it seemed to me that keeping that kind of freedom was even harder outside Czechoslovakia, because, although freedom there wasn’t political freedom, the lack of another freedom there– the freedom to make money–forced us to do things we believed in, that interested us, and that we liked to do.” – Josef Koudelka

Koudelka admits that if it wasn’t for his freedom of travel– he couldn’t make many of the photographs that ended up in “Exiles”. However on the other hand, he still does mention that he did have freedom to photography (while he was still living in Czechoslovakia).

Takeaway point:

I think this is a great point to note for those of us who don’t have the freedom to travel. We should know that we can still find space for our work and photography– and we don’t necessarily need to go far away to take photographs.

Koudelka also sees the ultimate freedom as doing what you want to do– things that you believe in, things that interest you, and things you like to do.

So don’t let the fact that you have a full-time job, a family, or whatever hold you back from your photography. If you have even a little space or time in your life to carve out for your photography– that is all you need. As long as you have enough freedom to make the photos you want, you should be happy and content.

3. On not owning anything

“After I left, I tried to avoid owning anything. I didn’t pay rent for sixteen years. I realized that I could live and travel on the money that I would have spent on a flat. I knew that I didn’t need much to function– some food and a good night’s sleep. I learned to sleep anywhere and under any circumstances. I had a rule, ”Don’t worry where you are going to sleep, so far you’ve slept almost every night, and you’ll sleep again tonight. And if you sleep outdoors, you might have two choices– to be afraid that something might happen to you and then you won’t sleep well, or accept the fact that anything might happen and get a good night’s sleep…” – Josef Koudelka

Many of us envy the life and photography of Koudelka. After all, who wouldn’t want to live the life of a nomad, to travel the world, and photograph to our heart’s content (without having to do work we don’t want to do?)

How did Koudelka do it?

Easy– he made sacrifices. Huge sacrifices. He lived barely scraping by– and made it a personal note not to own anything, not to pay for rent, and that he only needed a little bit of food and sleep to function/survive.

This makes me think of some quotes from the movie Fight Club (which talks a lot about how not owning material possessions can help us have more freedom: freedom of time, freedom to travel, and freedom to do what we want to do):

- “The things you own end up owning you.”

- “It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.”

- “You’re not your job. You’re not how much money you have in the bank. You’re not the car you drive. You’re not the contents of your wallet. You’re not your fucking khakis. You’re the all-singing, all-dancing crap of the world.”

- “Reject the basic assumptions of civilization, especially the importance of material possessions.”

- “We’re consumers. We are the byproducts of a lifestyle obsession. Murder, crime, poverty, these things don’t concern me. What concerns me are celebrity magazines, television with 500 channels, some guy’s name on my underwear. Rogaine, Viagra, Olestra…Fuck Martha Stewart. Martha’s polishing the brass on the Titanic. It’s all going down, man. So fuck off with your sofa units and strine green stripe patterns.”

Takeaway point:

Now I’m not advocating us to be a bunch of hippies, quit our jobs, leave our families and loved ones, and become nomads and photographers like Koudelka.

What I am saying is that know that sometimes when we worry and fuss too much about money, our jobs, and material possessions– that we have less freedom in our lives.

I know from personal experiences that money doesn’t buy me happiness. The only good use I have found for money is giving me the freedom of time and attention– to do what I love doing (writing for this blog, teaching, and sharing the love of street photography).

So rather than putting in extra work hours at your 9-5 job, perhaps you can use that time to shoot more. Rather than staying late at the office, use that time to study more photography books. Rather than reading gear blogs online and lusting after that new camera– perhaps you can look at inspirational photos from Magnum photographers on the Magnum Photos website.

Don’t get me wrong– I am a total sucker for materialism and wanting to buy shit (I know I don’t really need). But whenever I have an urge to buy a new camera, I think to myself: how many rolls of film, how many flights, how many photography books can this buy me? I also remind myself that it is experiences (not material possessions) which buy us happiness in life.

3. On taking photographs

“What I needed most was to travel so that I could take photographs. Apart from that, I didn’t want to have what people call a ‘home.’ I didn’t want to have the desire to return somewhere. I needed to know that nothing was waiting for me anywhere, that the place I was supposed to be where I was at the moment. I once met a great guy, a Yugoslavian gypsy. We became friends. One day he told me, ”Josef, you’ve traveled for so many years, never stopped; you’ve seen lots of people and countries, all sorts of places. Tell me which place is the best. Where would you like to stay?“ I didn’t say anything. Just as I was about to leave, he asked again. I didn’t want to answer him, but he kept on insisting. Finally he said, ”You know, I’ve figured it out! You don’t want to answer because you still haven’t found the best place. You travel because you’re still trying to find it.“ ”My friend, I replied, “you’ve got it all wrong. I’m desperately trying not to find that place.”

Koudelka realized that for his personal life– he needed to travel to take photographs. He also vehemently opposed on having a “home” — he was a traveler with no intention of returning.

Takeaway point:

There is a saying that “the journey is the reward” — that in life (and certainly in photography) — the experience and process of living life and taking photos is more important than the final outcome.

For example, I find the greatest joy not in completing photography projects– but in the pursuit. I love shooting, I love editing and sequencing, I love getting feedback and critique– and I like publishing the work at the end. But once I have a body of work that is published, I get a bit depressive– because I no longer have a purpose, a goal, or something I am working towards.

I also feel the same with traveling. I enjoy traveling the most when I am in the midst of traveling. Once I get back home– the joy of traveling sort of wears off. After too much time at home I get antsy– and want to hit the road again.

The same thing is in life. It is John Lennon who said, “Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.” We sometimes get too focused on the goals and outcomes of our life (earning more money, buying a house, buying a new car, buying a new camera, whatever) that we forget to enjoy, appreciate, and savour the journey.

So when it comes to photography– enjoy the process, experience, and journey.

4. On taking your time

“Exiles,” Koudelka explains, “is the title that my editor Robert Delpire gave to a group of photographs we originally selected in the early 1980s– mainly from those I made after I left Czechoslovakia in 1970. The very first dummy was made in 1983. Now, thirty years and many dummies later, we have made the third and final version of this book. It takes a while. You go through life, take photographs, the images together make some sort of sense. That’s how “Exiles” came about.”

I am often in a rush to shoot, edit, and complete projects. I am from the digital generation where everything is about instant gratification. I hate waiting for stuff. I even get frustrated when my smartphone takes longer than a second to geo-locate me on Google Maps– or when it lags when I am searching for something on Google.

But one thing that Koudelka has taught me is the importance of being patient, waiting, and being diligent with our work and photography. Koudelka inspires me greatly, because most of his great projects have taken him over a decade. Contrary to today’s Instagram world, he focuses on the slow and methodical approach– whereas we are obsessed with instant gratification in photography.

On this blog, I often share the idea to let your photos “marinate” — to sit on them for a long time (after shooting them) before deciding whether they are any good or not.

For example, I have close to 200 rolls of Kodak Portra 400 that I’ve shot over the last 11 months that I haven’t processed yet. I know when I get the film processed, I will be able to be more objective in terms of editing my work (deciding which to keep, and which to ditch).

Takeaway point:

So don’t feel so rushed in your photography — take your time. Like Koudelka says, “It takes a while. You go through life, take photographs, the images make some sort of sense.”

At the end of our lives, I don’t think it will matter how many photographs we took, how many books we published, or how quickly we were able to put it out there. We will value the quality of our images, how personal and meaningful they are to us– and this often takes a long time.

5. How Koudelka/Delpire put together “Exiles”

“We put small prints on a table,” continues Delpire. “Discovering subtleties in their associations. Constructing, without haste, a sequence that we looked at afresh after a few days. The pleasure of putting it together. And Josef would call me to tell me that he had found some real improvement. Sometimes just one image added to the sequence. An image that had been overlooked but that now seemed meaningful.”

One of the great ways a lot of photographers edit/sequence their work for books and projects is to print small prints on a table, and re-arrange them. This can help you create pairing associations, create a sequence, and create a flow for the book or project.

Also another key takeaway I learned is the importance of a single image– how one image can make a huge improvement to the sequence of a book. And I am sure it goes the opposite way: sometimes taking a photo away from a sequence can make the whole stronger as well.

Takeaway point:

When you are working on a project or a book– make it physical. Print out small 4×6 prints (they don’t need to be expensive) — and have fun. Be a child again. Throw all your prints on a table (or on the ground), and shift them around. Invite friends and other photographers you trust. Ask them to pair your images together — and ask them to find associations in your images. Ask for their feedback in terms of editing (which to keep, which to ditch), and possible sequencing ideas.

If you want to do it digitally– you can also do it via an iPad via the default “Photos” application. Of course this isn’t as good as the “real thing” — but a good alternative if you are on-the-go.

6. On living as an “Exile”

“Josef lived his ‘exile’ the way he always lived and will live– in a permanent quest. The world is his. As long as he has a camera in his hand.” – Robert Delpire

“My feeling is that Josef has always been stateless. He loves to photograph and so he travels. He loves to be on the move. He needs and asks for very little. He does what he needs to do to take the photographs he wants to take. Still, after so many years, he will sometimes sleep in Magnum’s offices. He searches for beauty, and understands place. But this understanding of place is not about political events, not about an idea of home, and is not sentimental. People and landscapes interest him, and he knows very well how to adapt himself to any situation that may present itself.” – Robert Delpire

I think one of the most important things as a photographer is to be adaptive– to adapt to certain environments, to adapt when working on projects (knowing when to change or ditch a project), and knowing how to adapt when shooting certain areas or individuals.

As an exile, Koudelka decided to constantly be on the move, without a home, and finds this as a “permanent quest.” He also knows that he can survive off very little– and therefore he needs (and asks for) very little. This gives him the freedom to photograph what he wants, how he wants, in pursuit of beauty through the people and landscapes he shoots.

Takeaway point:

Know what you are interested in– and pursue it. Know that as a photographer, you don’t need much to make meaningful photographs. All the cameras we have are more than capable to photograph amazing images (even your smartphone will do). We have no excuses to not pursue (photographically) what interests us– with passion, love, and fervor.

Know how to be adaptive in your photography also. The photography you shoot doesn’t always need to be “street photography”. Perhaps landscapes and portraits interest you– pursue that as well. Koudelka — having shot mostly 35mm black and white film for several decades, now shoots panoramic landscapes (on digital).

Keep adapting or die.

7. The world is yours

“When I left our village where my family lived, at the age of 14 to study in Prague, my father said, ‘Go and show what you’re made of– the world is yours.’ For almost 20 years after I left Czechoslovakia, I traveled, taking photographs in Western Europe. I was not allowed to go to the countries of Eastern and Central Europe. After 16 years of being stateless I was naturalized in France. I received my passport in 1987. But even though now, at 76, I have two places where I can work– in Paris and in Prague– I keep moving, continuing.”

The last, most moving, and inspirational quote I got from “Exiles” is: “Go and show what you’re made of– the world is yours.”

Takeaway point:

Life is short. The world is big. There are endless possibilities for us as human beings and photographers.

There is still so much unexplored areas photographically. Not everything has been shot before. Even if it has been, you haven’t photographed it before.

Know that you have no limits– the world is yours to photograph.

So keep moving, keep continuing your journey in photography, and keep shooting.

“Exiles“: The Book and Photos

You can see all of the photos from this new print of “Exiles” on the Magnum photos website here.

I will include the images that I find personally interesting, and share some of my personal thoughts:

Structure of “Exiles”

“Exiles” is a total of 75 images, and broken down into 7 different “Chapters”. Each chapter is almost like a mini-narrative within the greater story of “Exiles”. Each Chapter has 8-13 images, and with the earlier chapters having more images. What this does is give “Exiles” a good flow, structure, and narrative. Here is the breakdown:

- 1 image in introduction

- 13 images in Chapter 1

- 12 images in Chapter 2

- 12 images in Chapter 3

- 11 images in Chapter 4

- 9 images in Chapter 5

- 8 images in Chapter 6

- 9 images in Chapter 7

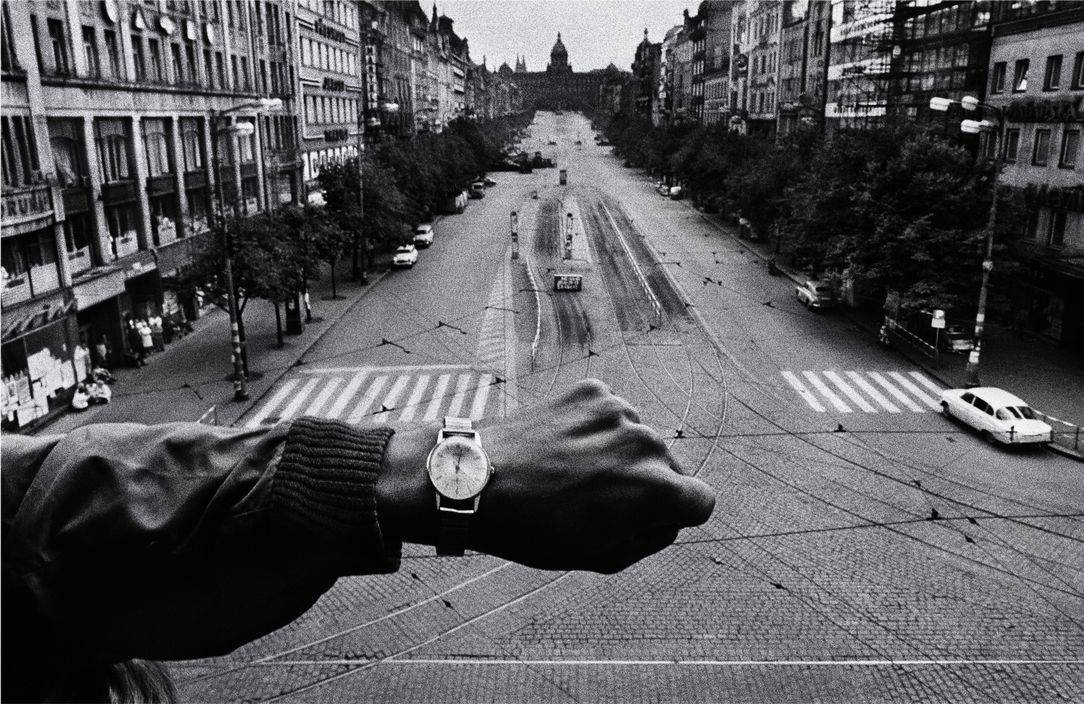

Image #1: CZECHOSLOVAKIA. Prague. August 1968. Warsaw Pact troops invade Prague. In front of the Radio Headquarters.

This starting image is one of my favorite images from Koudelka– him looking over the empty streets of Prague just as the Russians are invading. The text that accompanies this image in the book reads:

“I dedicate this book to all who have helped me since I left Czechoslovakia. Without them, many of the photographs in this book would not exist.”

For me the image is one of my all-time favorites– for many different reasons.

First of all, I love how you can see the time in Koudelka’s watch which reads (I believe) 6:03 and 23 seconds. I always find it fascinating to not only date-stamp (but to time-stamp) an image. It almost makes the event seem so much more real (seeing a clock in an image). Not only that, but it really shows the power of photography to literally “stop time”.

Furthermore, the way that Koudelka’s arm is positioned makes it feel like it is your own arm– outstretched and looking out into the empty square. It makes you feel like you are really there.

And to see the empty streets of Prague is eerie– with (what I think) is the capital building in the background. There are beautiful converging lines in the picture — which gives you a sense of depth in the image, and the placement of Koudelka’s arm is perfect. Seeing the additional curving lines in the streets and the stark vertical lines of the crosswalk also is visually appealing to me:

Chapter 1

“Exiles” is separated into 7 different chapters, here is the first chapter:

Image #2: GREAT BRITAIN. England. 1976.

The second image is also a great transition in the book. Here you see a man looking away, with an empty road in front of him.

I love how dynamic the image is- with the edge of the brick wall, the position of the man’s head (turned right)– and the empty road that is in front of him. The grittiness of the environment and graininess of the sky gives the photo a very dark, looming feeling. To me the photograph makes me think that the man is a metaphor for Koudelka– he is unsure which direction in life to head. Should he continue down the road in front of him, or perhaps veer off to the left?

Furthermore, what is great about this image is the strong “figure-to-ground” (or contrast) of this image: the man is separated from the background with the white space around his head. I have highlighted the white-space around his head in blue:

Furthermore, if you blur the background (the figure-to-ground test)– you can see there is good separation from the man and background:

Image #3: SPAIN. Andalucia. Sevilla. 1978.

This next image is of a monkey in a zoo– chained up and either biting or licking itself. The photograph feels stark– with the harsh white highlights of the wall behind the monkey and the posture of the monkey.

Perhaps the monkey is a symbol of us as humans– we locked up, caged, and chained in a zoo. We have no freedom– no way out.

Image #4: IRELAND. 1976.

This next image has always been quite of an enigma to me. At first glance, it looks like all these men are caged in some sort of prison or cell. You can’t see any of their faces– and they are wearing these dark and mysterious clothes.

Upon closer inspection– it looks like they’re taking a piss. But you still have this ominous barbed wire on the top of the frame.

Visually the image has good separation of the subjects in the photograph– and strong diagonal and leading lines in the image.

But what is Koudelka trying to say through the photo? I’m not quite sure– perhaps Koudelka is painting a grim picture of mankind as just these miserable old men pissing on barren concrete walls — all while being trapped in?

Anyways this is just my random interpretation– the good thing about photography and especially photography books: it is open to interpretation.

Image #5: FRANCE. Paris. The Louvre Museum. 1975.

This image we see a quite well-dressed woman looking out– upon first glance I thought she was sitting on the stone in the bottom left-corner of the image. Upon closer inspection, it appears she is in motion– walking to the right of the frame.

She has this fascinating look in her face– lips tightly held, slightly puckered– and her eyes look blank. It gives her the appearance of being sullen and pensive.

Compositionally, the image has great structure and form. There are strong horizontals, squares, and rectangles all throughout the frame– which give it harmony and order:

In terms of the sequence of images– she is almost looking out– and it makes a great transition image (to the next image of a man lying on a stone bench). She almost seems to be looking over him– judging him.

Image #6: ITALY. Sicily. Palermo. Mental hospital. 1984.

This man is presumably from a mental hospital (as noted by the caption)– and you see him passed out, lying on this concrete bench– almost like he is in a casket. His eyes are closed, and his face looks like it has been turned to stone as well.

The image is stark, and also has strong diagonals which make it more dynamic (compositionally speaking):

The image makes me think about death– which goes well with the whole dark mood of Exiles.

Image #7: FRANCE. Paris. 1980.

In this frame we see all of these legs– marching in perfect “V” formation, and their ominous shadows creating a strong diagonal composition in the frame:

The image makes me think of anonymous soldiers– all marching in unison. They look ominous– almost like the secret police. You can’t see any of their faces, which makes the image even more haunting.

I also feel this makes for another strong transition shot into the next image– which is of a stark shadow which almost looks like a lightning bolt:

Image #8: SWITZERLAND. Basel. 1978.

I think this kind of image is interesting– because it doesn’t have any people, and is a purely graphic image. I think a casual viewer might just look at the image and say, “I don’t get it– it just a photo of a shadow and a streak of light. I could have shot that, why is it in the book?”

For me, I have started to realize that in photography books– it isn’t just the single images which make the book. It is about the quiet photos in-between. Images that are more “transition” shots– and also act as punctuation marks in a book– which give it rhythm and flow.

When I look at the image, I see a lightning bolt. I think of power, Zeus, and strength. It also can be a sign of death (thinking of when lightning bolts hit human beings).

Image #9: FRANCE. Hauts-de-Seine. Parc de Sceaux. 1987.

This image has to be one of my favorite photos by Koudelka. It looks like a vampire dog from hell — and the stark black outline against the dirty white snow gives it a very dark and menacing feeling. The dog it also turned straight towards Koudelka (or the viewer)– and it almost looks like it is beckoning us to follow it. Either that, or the dog is about to jump towards us, lash at us, or even kill us.

Compositionally, the image has very strong “figure-to-ground” — the dark silhouette of the dog goes perfectly against the white background:

If we blurred our eyes, you can still see strong separation of the dog from the background:

This has to be one of Koudelka’s strongest images in the book (like a punch to the face)– and you can see how Koudelka slows down the pace of images after this image.

Image #10: SPAIN. Asturias. Oviedo. Dia de America Festival. 1973.

This image is of two men in what appears to be a train. The guy on the left is totally passed out, with his eyes closed shut, mouth open (probably snoring), and hands clasped. You see another man in the shadows on the far right of the frame– also hands clasped– looking away.

Frankly the shot isn’t my favorite in the book– and I think it could have been edited out (or perhaps substituted for another image).

It does make sense in terms of the sequence of the book– as you see the next image is of a shadow of a bridge. Perhaps the narrative is that these two men are on the train, and then the next shot you are looking out of the train to the countryside? Perhaps these two men are accompanying Koudelka on his train journey (going somewhere?)

Image #11: ITALY. 1982.

In this image, you see a shadow of a bridge, and Koudelka has purposefully tilted his camera to give the image a much more strong diagonal composition. The image is a bit dizzying, as the perspective is crooked– and makes me feel like I’m about to fall out of the train from where I think Koudelka shot it from.

I think this image is a good transition shot– in which you continue to follow Koudelka’s journey throughout “Exiles”.

Image #12: TURKEY. Cappadocia. 1984.

One thing I love about “Exiles” is how he incorporates a lot of symbolism– and the images are open-ended, meaning, the viewer can interpret his/her own message from the images, narrative, and story.

So for this image, you see an overturned turtle on its back. As we all know, a turtle flipped on its own back cannot get back up again. And of course, if a turtle cannot flip itself up again– it will starve and die.

Perhaps Koudelka is making the overturned turtle as a symbol for humanity. Many of us are overturned– places in our lives where we feel helpless. We need someone to help flip us upright again– or we will die.

Image #13: FRANCE. 1980.

Once again, we have another graphic image (similar to image #8) — this can perhaps be like a “Rorschach ink-blot“– we can interpret it however we would like. To me it is a sign of death and destruction.

This graphical image is also reminiscent of Koudelka’s early work– in which he has extreme shadows, light, and contrast:

Image #14: ITALY. Naples. 1980.

The final image for “Chapter 1” is a bunch of stones and sticks– just lying against a stark black background. It is a good punctuation mark for the end of Chapter 1. It is another open-ended dark, stark, and depressing image that perhaps shows the ruin of humanity in one way or another.

Chapter 2

Image #15: SPAIN. Valencia. 1973.

This image to start Chapter 2 of “Exiles” is beautiful. There is simple geometry, form, and on a cold, dark, and rainy day– there is a hope of flowers being carried by this almost headless looking person.

Image #16: SPAIN. Grenada. 1971.

This next image is a brilliant one: you see a man without a leg (on a crutch) walking down this lonesome alleyway in Spain, with a dog perched high on top of the frame–looking out the other way.

What comes to my mind is: what is the connection between this legless man and this dog? They are both looking different directions (which gives a strong sense of tension in the frame). Perhaps you can interpret the image as the dog having freedom (perfectly physically able)– whereas the man is crippled and limited in his movement.

And when you look down the alley, there are 2 other men (perfectly spaced out in the frame) – all going down:

Image #17: SPAIN. 1973.

This is probably one of the happier images in “Exiles”– you see a man and presumably his son. The man has a smile on his face, and has his arm on his son’s shoulder. The son has his right arm about to hug the father– or ask him to play with him.

But from the corner in the right of the frame– you see an ominous shadow (of a mysterious person). Who is this shadow– is this mysterious man going to kidnap the son and take him away?

I personally think that Koudelka could have also edited out this shot from “Exiles” — but I think having a little bit of happiness and hope does liven up the book a bit.

Image #18: IRELAND. 1971.

I quite like this image in the sequence because it breaks up all of the men in the previous images. Here we see a bunch of middle-aged to elderly women enjoying a cup of coffee around a stark table. You see the woman in the far right looking menacingly and suspiciously to somebody in the far right of the room– with the woman in the top-right edging over to see what is going on. You see the other women enjoying their coffee (or whatever beverage) amongst one another.

One continued thing that I love about the imagery of Koudelka (especially in “Exiles”) is the emotions he captures. He caught a great “decisive moment” in the woman’s stare — and there is a great deal of mystery of what they are looking out at. I love images that are open-ended like this.

This image is also a nice transition to the next image– of a man who has appeared to have stumbled, and is trying to crawl up a set of stairs:

Image #19: SPAIN. 1971.

This is another superb image– it is an open-ended image which invites you, the viewer to make up your own story.

Is the man passed out from a long night of drinking– and is now trying to crawl up the stairs? Did he just fall down the stairs, and is huddled at the bottom?

To me the staircase is also a strong metaphor. The staircase can be a metaphor in the sense that we are always trying to climb it– trying to advance and raise ourselves out of dire situations in life. But we are weak, huddled at the bottom– and have a long way up.

Image #20: SPAIN. Barcelona. 1973.

In this image you see a woman in the middle of the street who looks almost like a witch. The image is dark and mysterious– who is this woman, and who is she going after?

Image #21: ITALY. Naples. 1980.

You then have the next image of these two boys looking out — perhaps they are watching out for the witch-like woman in image #20?

The image reminds me of a Henri Cartier-Bresson shot in the sense that it has strong verticals, simple form and composition– and is a very “quiet” photo. It breaks up the dark mood and feeling of the previous images– but I personally don’t think it is the strongest image in the book, and perhaps it could have been edited out.

Image #22: SWITZERLAND. 1979.

This image is a great transition from the previous image in the sense that it looks like it is a bunch of pillars or pieces of wood that has fallen down. It reminds me of the previous shot of image #22 (of the strong verticals). Perhaps the pillars of image #22 have fallen down?

Koudelka is quite good in using these fallen down pieces of rubbish as breaks in the narrative and sequencing in “Exiles”. It echoes that of Image #8 (lightning bolt) and Image #14 (discarded sticks and stones).

Not a strong image by itself– but I think the point isn’t for this image to be a stand-alone image. It is for the flow and narrative of “Exiles”.

Image #23: GREAT-BRITAIN. London. 1977.

Here is an incredibly powerful image by Koudelka– of a dark and mysterious man in a hat broodingly approaching us, with a menacing look– and a man in the background (also in silhouette) walking away. The image has strong diagonals, textures in the wall, torn up newspapers in the bottom of the frame) — which gives the image a post-apocolyptic feel.

It is a photograph that makes me wonder what the man’s intentions are. Why is he looking at me so menacingly? It is also the fact that his face is obscured which gives the photo much more mystery.

Image #24: FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF YUGOSLAVIA. Serbia. 1994

I also love this image in the sequence– because we go from wondering who the man is in the previous image– and then suddenly seeing this poster of a man’s eyes scratched out.

It is a very powerful image– one that jumped off of the page and looked straight at me.

It reminds me of 1984– like a “big brother” who is also watching you. But in this case, there has been some sort of rebellion uprising– which is trying to fight this authoritarian dictator:

I also can’t help but feel what Koudelka’s feelings were when he shot the image — his pain, frustration, and anger towards the invaders of Prague.

Image #25: ITALY. Sicily. Palermo. 1985. Mental hospital.

In this image you then see all of these people who are on the ground– it almost looks like they are afraid and cowering from the dictator-like figure on the poster in the previous image.

What I love about this image is the feeling of death and destruction (the men on the bottom of the frame, curled up as if they were dead)– while there is great movement and spacing of the subjects on top of the frame:

One of his strongest images in the book as well.

Image #26: GREECE. 1981.

I love how this image fits inside the sequence– it is a capital “E” (perhaps a hint at “Exiles”) with what looks like blood dripping from the “E”.

It is a powerful, strong, and symbolic image. And also a suitable concluding image for Chapter #2.

Chapter #3

Image #27: FRANCE. Brittany. Gypsies. 1973.

I noticed in Chapter 3, the images tend to be a little more upbeat and lively than the previous 2 chapters– which are more dark and grim.

Here we have a beautifully composed photograph of 3 “Gypsies” all enjoying themselves in a field. There is great separation of all of the figures– and compositionally works very well. You have the man in the far left, throwing the ball in the air (with the ball suspended), the guy in the bottom relaxing, the guy in the middle looking over (not sure where), a horse in the top right facing left, and a little square in the top of the frame (contrasts well against the ball).

The photograph doesn’t really say much to me– it is just a well-crafted image with nice composition, form, and a warm sense of how it feels to just relax on a hill on a warm day.

Image #28: CZECHOSLOVAKIA. Moravia. Olomouc. 1968. Carnival.

This image is also one of Koudelka’s most famous single images– of a boy (dressed up as an angel) who looks a bit gloomy– riding a bicycle. You have a woman in the far left looking over (perhaps his mother) and then you got horses in the far right of the frame.

Upon first glance it is quite funny to think of an angel resorting to a bicycle for transport. Because the horse is overlapped with the bicycle– it almost gives you the visual illusion that the boy is propelling the entire horse forwards. Also as a random note: note how you had a horse in the previous image, and also this image (a good sequencing link).

The angel of this boy is also a great introduction to a series of images which are religious-based (Image #29 of what I first thought was a funeral, but is actually of a church) and image #30 (of a boy about to kiss the statue of the virgin mary), and image #32 (of an actual funeral).

Image #29: IRELAND. 1971.

In this image you see three figures: the virgin mary statue, the man int he bottom left, and a young-looking boy (or man) on the far right of the frame.

In the top-right of the frame, you see the words “cream” — but with the window pane intersecting it, it looks like it says “dream” (you can interpret this however you would like).

The man in the bottom left looks quite pensive, based on his eyes and the way he is crossing his fingers. He is covered in a blanket– he almost looks like he is a corpse.

Image #30: FRANCE. Lourdes. 1973.

To transition to the next image, you see a boy tenderly about to kiss a statue of mary– while in the bottom-left of the frame you see the statue of Jesus being crucified. In the top-right of the frame, there is a big crowd– that seems to not know what is going on. But in the bottom-right of the frame, you see a young boy with his shoes in his hands– looking over in a curious-styled way.

Image #32: IRELAND. Croagh Patrick Pilgrimage. 1972.

In this image, you see three men hunched over on their hiking sticks, hunched over at the summit of Croagh Patrick (a mountain in Ireland). According to Wikipedia, Croagh Patrick is a site of Christian pilgrimage associated with Saint Patrick (who reputedly fasted on the summit for forty days in the fifth century A.D.) As a religious pilgrimage, thousands of people climb the mountain every Reek Sunday, which is the last Sunday in July.

The photograph itself has feelings of religious overtones for me– with these men hunched over, looking all these different directions– perhaps seeking some sort of direction or salvation in their life? I love how all of their gazes go in opposite ways– which makes the photograph much more dynamic:

Image #32: ROMANIA. 1968. Gypsies.

Then for this image, it transitions into a very obvious religious image– a “Gypsy” funeral. Koudelka photographed this at the “decisive moment” — when the casket is about to be put over the person. You have faceless hands coming from all the sides of the frame– and you have a weeping woman in the top of the frame.

Once again the themes of death and sorrow in “Exiles” flows deeply from this image.

Image #33: ITALY. Basilicate. Tricarico. 1980.

I’m not quite sure what this is an image of– but based on the sequencing of images– it looks like tattered rags. Perhaps this has something to do with a funeral? I’m not quite sure– but it is another “still life” photograph of torn rubbish which breaks the religious overtones of images #28-32.

Image #34: SPAIN. 1976.

This image is a direct homage to Koudelka’s first image in “Exiles” (image #1), shot at the Prague invasion of 1968. This image is shot around 8 years later– but this time he is looking out at a serene landscape.

When I see this image– I ask myself, “Why did Koudelka shoot this image? What personal significance does this image have for him?”

Perhaps if I was in his shoes– I would have thought to myself, “Man, a lot of time has passed since the Prague invasion of 1968. Times have changed. I am now relaxing, on the road, and taking a photo of this moment might be a nice memento to myself in the future.”

But once again, time is a strong symbol inside “Exiles” — how time passes, how it moves forward, and how it references the past.

Image #35: FRANCE. 1976.

This is actually one of my favorite images by Koudelka in “Exiles” — you see a “still life” photograph, with Koudelka enjoying a nice breakfast of apples, cheese, while there is destruction and terror in the world around him.

Some of the headlines read:

- “In Britain, some ideas to combat the drought”

- “10 said slain in Soweto as black strike holds”

- “Middle-class youths swell ranks of Argentine terrorists”

- “UN defers Vietnam’s application”

- “China rejects condolences from Soviet blue red parties”

It makes me moved– because a lot of photography is about capturing the past and memories.

Every photograph we shoot today will become “history” sometime in the future. It is hard because time moves slowly in the present– but it speeds up in the future.

It is easy for us to look back at this photograph (shot in 1976) and see how “vintage” it is. But if we were to take similar photographs today, we might look at them 40 years down the road and be amazed.

Image #36: SPAIN. 1975.

In this image, we see Koudelka kicking back, relaxing somewhere in Spain, with his legs outstretched against a tree.

It is another photograph in this sequence of seemingly “relaxed” photographs– with a more upbeat feeling.

Perhaps he photographed this to remember some of the nice parts of his life’s journey– the time where he was enjoying the nice sun in a meadow somewhere. It is a photograph that makes me happy– and appreciative of the small things in life (the joy of relaxing in nature).

Image #37: IRELAND. Aran Island. 1972.

Here we have a compositionally beautiful image– of a horse outstretched and feeding on some grass, with a winding road in the background, a small house, and some telephone wires. There are nice curves in this photograph which make it flow well:

I don’t see any obvious sequencing connection between this image and the prior images– except that it is another “quiet” and calm image — which is a suitable second-to-last photograph in Chapter #3.

Image #38: GB. ENGLAND.

The last image in Chapter #3 is a deceptively simple image of a scraggly looking tree, which is bending to the right of the frame (similar to the road bending to the right of the frame). You have strong graphical elements of a dotted line in the center of the frame– but it stops abruptly at the grass. The line suggests that you are following it, and suddenly you are at the “end of the road”.

The image to me has a symbolic message of: “This is the open road– take it wherever your heart wishes.”

Chapter #4

Image #39: SCOTLAND. Edinburgh. 1982.

This image is a suitable photo to start Chapter #4 — in the sense that it is a set of stairs which lead you downwards to this man– who encourages you to follow him.

Image #40: PORTUGAL. 1976.

This image is one of Koudelka’s compositionally most beautiful images. It almost looks like a surreal painting– you have strong symbolism of the little innocent girl talking and looking at an older woman (young vs old), the mysterious looking man on the top right of the frame with a top hat (with his shadow in the center of the frame), and the subtle little hook in the far left of the frame:

You also have 3 different subjects in this image, a young girl, an older woman, and an older male. The image has slightly ominous overtones– but a compositional beauty which makes it seem other-wordly.

Image #41: GB. ENGLAND. London. 1969.

The next image is a quite dramatic shift– where you see an abandoned baby in some dingy back-alley. It makes you immediately start questioning: “Who are the parents who just abandoned this poor baby? How is the baby going to survive? Is anybody going to save the baby?”

It makes me personally question humanity in general– and gives me a pessimistic view.

Image #42: SPAIN. 1971.

You then transition into a photograph of an old lady who looks like she has a hunch-back, cleaning a front door. Perhaps she is the woman who is going to save the baby (in the previous image)?

Compositionally, the photograph has great form and structure as well:

This is another key thing I notice in a lot of Koudelka’s images– his graceful compositions, many of which have good separation of subjects, a nice play between dark and white forms. Even in this image, you can see that the woman (with a dark shirt) stands out really well against the rest of the scene:

Image #43: SPAIN. 1976.

We then transition into a photograph of a wandering goat– not my favorite image in the book, but another symbol of freedom, wandering, and journeying into the unknown abyss.

Image #44: CZECHOSLOVAKIA. Moravia. Straznice. 1968. Folk Festival.

This image we have a peculiar image of a man with outstretched hands, one open and one closed, with some sort of puckering motion with his hands. I am not sure what he is saying or gesturing– but it certainly is a very energetic image. I think it adds to the flow of “Exiles”, working well as a “transition image”.

The image also has very strong “figure-to-ground” (contrast) with the man’s black silhouette against the white wall:

Image #45: IRELAND. 1971. Puck Fair.

In this image, you see a lot going on: a man in the bottom-left corner hunched over, perhaps drunk and hung over from partying earlier, a man with a hat in the center of the frame (perhaps also passed out), hugging the pole and hand on his leg, two guys in the center of the frame playing music, a mysterious man in the far left of the frame, and moving horses in the streets in the top-right of the frame.

It is a great scene with a lot of action, movement, and “mini-stories”.

Image #46: GREAT BRITAIN. England. 1972.

When I first looked at this image, I had a hard time deciphering it. But upon closer inspection, it appears to be a cat jumping off a wall– with its shadow projected on wall.

It is a photograph with a lot of tension, as Koudelka caught this great “decisive moment” — which propels the narrative of “Exiles” along very well.

Image #47: SPAIN. 1974.

In this image I get a strong feeling of “exile” in the sense that you have these two women who are cloaked — looking as if they are suffering (perhaps those flowers are for a funeral or a grave they are going to). While the two older women are walking towards us in the frame– there are two other men in the right of the frame moving into the frame– there is a tension of movement in both directions:

Image #48: SPAIN. Andalucia. Grenada. Guadix. 1971.

You then have an upbeat image– of perhaps some sort of festival in which they are shooting rockets. It has a very strong sense of energy and movement, and mystery with the silhouettes of the men (hard to see their faces).

Image #49: SWITZERLAND. Zurich. 1978.

In the last image, we have a cold, dark, and mysterious image of a snowy night in Switzerland– in which Koudelka shot this image with a flash. You see the reflection of a triangle in the left of the frame, and snow floating around in the background.

To me the image feels “magical” — like a frozen moment in time. It is a very suitable “concluding image” for Chapter #4.

Chapter #5

Image #50: SWITZERLAND. Basel. 1980.

To start Chapter #5, Koudelka leads with an image of a devil. It is a strong sinister image– and makes me think of ideas like, “the devils are among us” — and perhaps how Koudelka sees a lot of humanity. The devil is a strong symbol, which you can make up your own conclusions.

Image #51: ITALY. Sicily. Palermo. 1980.

In this image, you see a boy in the far left of the frame, and a ball that has been kicked over– I’m not quite sure what the symbolic reference of this image is (or what Koudelka is trying to say). Perhaps the message is about stray balls– like people who are off the right track? I think I’m over-analyzing and over-intellectualizing this image– but the ball leads into the next image, which is a strong one:

Image #52: GERMANY. Rhenania-Westphalia. Cologne. Carnival. 1979.

Here you have another mysterious image (reminds me of the devil photo of #50) — of a man covered up in paper, which makes him look like a ghost, mummy, or some sort of spirit.

The image is quite elegant, with the curving paper from the bottom-left of the frame, connecting to the center of the frame. I also get the sense that the “spirit” has turned around many times– and now is looking straight at me:

Image #53: SPAIN. Valencia. 1973.

The pace of the sequencing then speeds up– you see a well-dressed man (with hat, coat, and tie) walking around a back-alley, when you see some sort of cart moving in the background, with a creepy-looking statue or doll looking towards him (or us, the viewer).

Image #54: CZECHOSLOVAKIA. Prague. 1964.

In this image, you transition into an image of a woman (previous image being a man)– and in the background, you have what looks (another) abandoned baby. It looks like the woman is turning her back to the baby– and the baby looks on as helpless.

This reminds me of image #41 (of the other abandoned baby in the alleyway). What is Koudelka trying to say about us turning our back towards children and our future?

Image #55: GREAT-BRITAIN. England. Derbyshire. Buxton. Pop festival. 1973.

You then get an epic shot of a couple embracing themselves in what seems to be the aftermath of a pop festival in Derbyshire. There is just trash and desolation in the background– but in the midst of all of this, you have a couple holding one another (as if they are protecting themselves against the world).

If we think of the prior images as part of a sequence (Image #53-55) — you have a lone man, a lone woman, then them embracing in this image.

Image #56: SPAIN. Gypsy. 1973.

You then suddenly have a funny and odd image of a man, with his hands on his sides, looking curiously at a pigeon in the bottom of the frame.

For me, the image kind of kills the flow of the previous images– I wish this image wasn’t included, and it went straight to the next image:

Image #57: GREAT-BRITAIN. England. 1976.

You have another image of an open road– the lines in the road almost look like arrows pointing in different directions. It reminds me of other photographs Koudelka has in “Exiles” with leading lines (leading your eyes out of the frame) such as images #7, #19, #37, #38, #39, #43, #49.

Image #58: GREAT BRITAIN. England. 1969.

This image is also one of my favorites– and a quite charming one. You have a child buried in the leaves, almost as if he/she is hiding from the world. Koudelka shot this from a pretty low angle as well, which makes the perspective of the child more personal.

This is also an apt concluding image for Chapter #5– as it is an open-ended one.

Chapter #6

Image #59: GREAT-BRITAIN. London. 1976.

We then jump into Chapter #6, with an energetic image of a dog stretching and entering the frame of Koudelka– with a man in the background walking away.

This image is a perfect complement to the last image of Chapter #5 (image #58) of the child buried in the leaves (there are also fallen autumn leaves in this image).

The dog almost seems to beckon us into the frame– to continue us in the “Exiles” journey. It is also somewhat related to the dog of image #9 (but far less menacing).

Image #60: UNITED KINGDOM. Wales. 1977.

We then encounter an image of what looks like to be a doormat in a pile of straw, weeds, or grass.

To me the shot doesn’t say much– it is a nice image of forms (rectangles) and textures — but I think “Exiles” would have been stronger without this image.

Image #61: FRANCE. Bouches-du-Rhône. Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. 1974.

We then see an image of a woman, sitting in a chair, stretching her arms in some sort of interesting, dancer-like gesture. On the right of the frame, you see a little car– ready to go somewhere.

When I see cars, I think of freedom, road trips, and adventure. Perhaps this woman is beckoning us to follow her into the car, and countinue this journey?

Image #62: GB. England. 1982.

Koudelka has a fond love of landscapes (as all of his new recent work are panoramic landscapes). Here you have a very dynamic landscape of the sea, with the frame tilted, and strong diagonal lines of the wooden fence:

Image #63: IRELAND. 1978.

You then fall into this very haunting image by Koudelka– of an upside-down (I think crow). You also see how Koudelka tried to photograph this image to align the horizon of the image with the string holding the crow. What this does is flatten the perspective– and make the image seen even more direct.

What does an upside-down hanging crow mean? It certainly isn’t a happy image– it is a photo of death, and perhaps abandonment.

Image #64: ROMANIA. Constanta. 1994. Location shooting of the film ‘Ulysse’s Gaze’

Here we have an image which looks like the fallen arm of Stalin. It is interesting– as this is a pretty recent photograph by Koudelka (shot in 1994) — and isn’t actually a “real” statue. It was photographed as a prop for a film.

In the “Exiles” book, the captions are all in the beginning of the book– so as a viewer, you don’t actually know the back-story of this menacing arm.

This is what I think the beauty of photography books are– you can create a false story, narrative, and story.

When I see the arm of this statue– I think of totalitarian governments, dictatorship, but also perhaps freedom (the freedom fighters have cut down the arm of the dictator).

To me the image is a sign of hope and of change.

Image #65: PORTUGAL. 1979.

Here is another beautiful image of an open road– with beautiful textures, a grainy and dark sky– but a glimmer of hope from the shining reflection of the side-view mirror of a car.

Image #66: FRANCE. Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Calais. 1973.

One of Koudelka’s most iconic images– which is the last image of Chapter #6. You see a man looking out at a ship which is departing.

Here are some thoughts that go through my head when looking at this image:

- “Is the ship leaving without me?”

- “I wish I could go on these journeys — but I am too old, and it is too late.”

- “What kind of adventures could I go on, if I were only on that ship”

- “It looks like I missed my ship in life”

Once again– some of the strongest images in photography are the ones that are open-ended, and ask questions (and don’t provide answers). Koudelka does this best in “Exiles” with images that have mystery, symbolism, death, religion, life, and hope.

Chapter #7

We have finally arrived at Chapter #7 (thank you for the persistence of reading this far) — it has been a great journey so-far dissecting these images, the narrative, composition, emotion, and stories. Let us truck on:

Image #67: ITALY. Tuscany. Carrare. 1980.

The leading image of Chapter #7 is of a boulder with some wire– with a gloomy landscape in the background.

To me the shot doesn’t really say much to me, perhaps it is an image that suggests being grounded, or the aftermath of death or destruction? I think we could have been okay just transitioning into the next image:

Image #68: IRELAND. 1978.

This image we see a woman with wild hair blowing in the wind, as she is looking into the ocean. It reminds me of image #66 (of the man looking at the boat in the ocean).

The next several images in Chapter #7 have allusions to the water and ocean and sea– a metaphor for openness, freedom, and adventure.

Image #69: UNITED KINGDOM. Scotland. 1977.

We have a very suitable transitioning image here– of a seagull flying in the wind, with a look of grit and determination in its face. Thoughts of freedom, life, and flight come here.

Image #70: ROMANIA. Danube delta. Sulina. 1994.

Suddenly we are docked at the pier– with this image of an over-turned boat. The narrative begins to quiet down a little bit.

Image #71: PORTUGAL. 1979.

Here we have an absolute masterpiece of an image– in terms of composition and formalism. There are so many beautiful lines, curves, circles, and plays between dark and light (what they call “chiaroscuro” in art).

Perhaps this is the home that Koudelka wants to come back home to– but can’t for some reason? The image feels nostalgic– but also distant and mysterious. It doesn’t look like a real home– perhaps this is the place that Koudelka wants to avoid?

Image #72: ITALY. Sicily. Palermo. Psychiatric hospital. 1985.

Another beautiful image by Koudelka– ironically this beautiful image is in a psychiatric hospital. You see a naked man, what at first glance looks like a flower behind his back (not sure what the object actually is).

Regardless, I love his pose– he almost looks like a Roman statue, with his legs crossed and his arm behind his back.

The image also have beautiful shapes and forms– the strong horizontal and vertical lines, and all the squares in the frame.

Image #73: GB. Wales. 1974.

We then see another enigmatic image– this one of a lot of “shadow play” with a shadow of a chair on the far left of the frame, and a mysterious man in a hat in the bottom of the frame. You then have a television on top of the frame looking downwards.

I love the mystery of the image and the surrealism of the image– you can interpret the image however you would like. Perhaps the shadow of the man is a symbol of Koudelka himself– still constantly wandering.

Image #74: ITALY. 1981.

We are nearing the end of “Exiles” we have another “still life” photo — this one of crossed lines, draped canvas, all hastily patched together.

Not my favorite image either– I think some of Koudelka’s other “still life” photos are stronger– but it is a suitable, more “quiet” photo that works at the end of the book.

Image #75: IRELAND. Connacht. Aran Islands. 1977.

We have finally arrived at the last image of “Exiles” — of a beautiful sea. You see these wonderful ripples, lines, and movement in the water, with soft light hitting it from top.

To me the image says that Koudelka’s journey as an “exile” is still going– and the open sea is a metaphor for the world still being open to possibilities– to explore, to wander, and to continue to keep moving.

Conclusion

I personally learned a lot through just analyzing the images, the sequence, and editing of “Exiles” (in writing this post).

I think as I have had this time to meditate on the images and write about them– I have a greater appreciation for the book, and the work of Koudelka.

“Exiles” is not just a photography book– it is a personal journey of Koudelka’s life as an exile. To illustrate how he feels about the world, he uses dark, light, shadows, mystery, people, religion, death, life, and hope. Most of the images in the book are open-ended and can be interpreted however the viewer pleases. All of the “explanations” I provided in this review are just my own– my own interpretations. I use my own personal life experiences to tell the stories in my mind.

I think also what I learned from “Exiles” is how not every image needs to be a strong image– certain images are necessary for the flow and sequence of images. I see “Exiles” as a journey — and more of a movie than just a set of images. I also love how he used the different “chapters” to separate the images. There is a great sense of “pacing” of the images.

Although I do feel that Exiles could have used a slightly tighter edit (maybe around 5-6 fewer images)– the body of work is pretty bulletproof, and damn solid. Koudelka is a master of composition, capturing life, and capturing forms– even in the landscapes he shoots.

I hope to aspire to one day create a body of work that has the same amount of emotion and soul as “Exiles“.

If you enjoyed this review, I highly encourage you to purchase a copy of “Exiles“. I’m pretty sure it will sell out pretty soon (and end up re-selling for $300+) and the photos on the internet don’t do justice to the actual, beautifully printed images on paper.

You can also see all of the photos from “Exiles” on the Magnum Site.

Books similar to “Exiles”

If you enjoyed “Exiles”, here are some other photography books I would recommend:

- “Wonderland” by Jason Eskenazi

- “I, Tokyo” by Jacob Aue Sobol

- “The Americans” by Robert Frank

- “Veins” by Anders Petersen/Jacob Aue Sobol

Learn more about Josef Koudelka

- 10 Lessons Josef Koudelka Has Taught Me About Street Photography

- 7 Lessons Josef Koudelka Has Taught Me About Photography and Life

- 8 Rare Insights From an Interview with Josef Koudelka at Look3

- Street Photography Book Review: “Gypsies” by Josef Koudelka

- Magnum Portfolio: Josef Koudelka

My Top 10 Favorite Street Photography Books

If you currently don’t own any photography books and want to start your own library, below are my top-10 favorite street photography books. These are the books I would take if my house were burning down (and I could only keep 10 books):

- Magnum Contact Sheets (read my review)

- Dan Winters: Road to Seeing (read my review)

- Bruce Davidson: Subway

- Alex Webb: The Suffering Of Light

- Josef Koudelka: Gypsies (read my review)

- William Eggleston: Chromes

- Robert Frank: The Americans (read my review)

- Martin Parr: The Last Resort (read my review)

- Jason Eskenazi: Wonderland (read the interview)

- Trent Parke: Minutes to Midnight (read my review)

You can also see the full list of my favorite street photography books.