Your cart is currently empty!

17 Lessons Henri Cartier-Bresson Has Taught Me About Street Photography

As this article is very long, I recommend reading this by saving it to Pocket or Instapaper. All photos in this article are copyrighted by Henri Cartier Bresson / Magnum Photos.

I recently picked up a copy of “The Mind’s Eye” – which is a great compilation of thoughts and philosophies Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote. Aperture published this great volume (as they are an amazing non-profit dedicated to promoting photography, education, and great ideas).

Ever since I have been back home, I have been dedicating more of my energy, attention, and focus to great photography books – and trying to distill the information. I’ve learned all of these great lessons personally– and I want to share that information with you.

Personal thoughts on Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson was one of the first street photographers who deeply inspired my photography and work. Of course– whenever you Google “Street photography” he is always the photographer that comes up the first (then the fact that he shot with a Leica camera, which takes a lot of photographers, including myself, down a rabbit hole of wanting to purchase a Leica camera to get great shots like him).

Anyways, early on– I was fascinated with this concept of “the decisive moment” – how Henri Cartier-Bresson was able to capture the “peak moment” of every photographic scene. He was able to time his images perfectly, composing his photographs with great elegance (and supposed “ease”).

After a few years of research and getting more passionate about street photography– I soon started to learn about the “myth of the decisive moment” – in the sense that Henri Cartier-Bresson didn’t just shoot 1 photo of a single scene. If he saw a good scene, he would “work the scene” – shooting sometimes 20+ images of one scene, and would try to time the scene as best as possible:

Of course Henri Cartier-Bresson never claimed to only take 1 photo of a certain scene. However I think a lot of street photographers make the wrong assumption that “the decisive moment” is just one moment. Rather in reality, there can be dozens of different “decisive moments”, even within a certain scene.

Regardless to say– Henri Cartier-Bresson was one of the earliest teachers I had in terms of teaching me about composition, timing, and “the beauty of the mundane” (ordinary moments). While I wish he could have taught me directly (haha I wish), his photography was the greatest inspiration.

Henri Cartier-Bresson: a painter or a photographer?

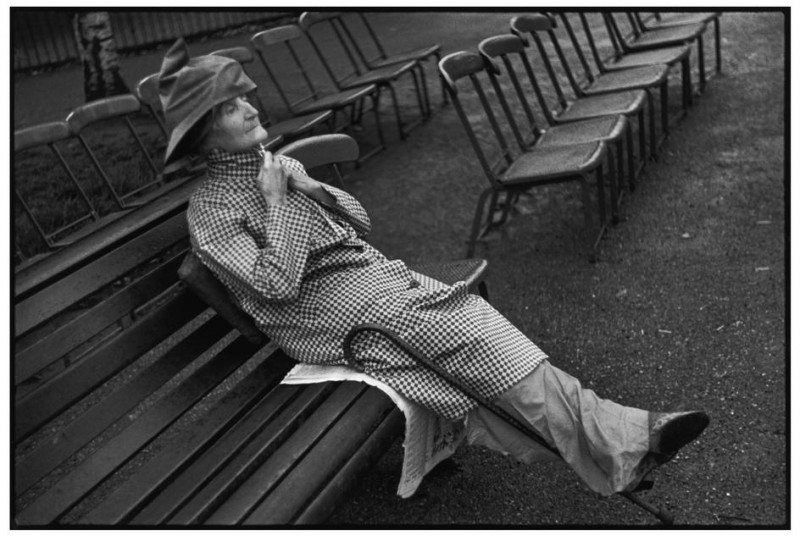

FRANCE. Paris. 1992.

One of the most interesting things I’ve learned about Henri Cartier-Bresson was that he started off interested in painting, and found photography as a way to make “instant sketches.” In-fact, I think that he secretly wanted to be a painter all along, but found photography to be his natural calling. In-fact, towards the end of his life (after 30+ years of photography), he gave up shooting all together– and decided to pursue drawing and painting full-time for the rest of his life.

So why did Henri Cartier-Bresson decide to quit photography – and focus on painting instead? The closest “evidence” I have found was in this letter he wrote about his friend Sam Szafran in “The Mind’s Eye”.

“Sam [Szafran]– I owe him a lot; he is one of those very rare people, along with Teriade, who some 25 years ago encouraged me to quit playing the same old instrument forever.

Cartier-Bresson starts off by saying that Sam encouraged him to “quit playing the sale old instrument forever”– perhaps signaling that he was tired of playing his same old instrument (the Leica) – and perhaps felt that he was just repeating himself (just working in black and white, film, mostly 50mm, and capturing “decisive moments”).

Perhaps Cartier-Bresson got bored of playing this instrument (the camera) over-and-over again (just as some musicians get bored of playing the same instrument, or how some painters like Picasso get bored painting the same old thing).

Cartier-Bresson continues:

To those who were surprised that I abandoned photography, he says: “Let him draw if that’s what he likes, and anyway, he never stopped taking photographs, only now it isn’t with a camera but mentally.”

Sam Szafran defended Cartier-Bresson by saying that “he never stopped taking photographs, only now it isn’t with a camera but mentally”.

I think this is an interesting point– perhaps it wasn’t photography, which ultimately interested Cartier-Bresson, but it was just capturing emotions and life in general. Whether this was done with a camera, a pen, or a paintbrush– I think the tool mattered a lot less for Cartier-Bresson (than the ultimate meaning he was trying to gain from it).

Josef Koudelka also made an interesting point that he thinks the reason why Cartier-Bresson gave up photography was because he didn’t push himself as a photographer hard enough– that he didn’t evolve in his photography (and kept shooting the same way over-and-over again, which could lead to boredom and repetition). Koudelka, on the other hand, has evolved much with his photography– switching from 35mm black-and-white to shooting panoramics.

At the moment, I understand that Koudelka shoots his panoramics digitally with a medium-format digital camera (the Leica S2). Even Lee Friedlander (after shooting decades with his Leica), moved up to shooting 6×6 medium-format photos on a film Hasselblad.

Case-in-point: perhaps photographers need to evolve the way they shoot (and sometimes their equipment, but not always).

But in the end, I still greatly admire Cartier-Bresson for giving up photography and pursuing what I think his “true” passion was– painting. It takes a lot of courage for someone who was considered a “master” and pioneer of the genre of photography to give up photography all together. He disregarded what the critics said, the opinions others had of him, and followed his own path and heart. You go Cartier-Bresson.

The life and philosophy of Cartier-Bresson

Many suspect that Cartier-Bresson was a Buddhist, as his writings and philosophies seem to reflect that. In-fact, one of the books that inspired him the most in his photography was “Zen in the art of archery” by Eugen Herrigel– a book that focuses on archery (there seems to be a lot of parallels between archery, photography, and a lot of other “meditative sports” in general). If you are interested in Zen, I recommend reading my article: “Zen in the Art of Street Photography“.

Based on “The Mind’s Eye” I have distilled the key philosophies from Cartier-Bresson. This is all just my interpretation– and the lessons I’ve personally learned. But the reason I am compiling all of this information is that I hope it is useful to you, my fellow street photography friend, that it inspires you in one way or another. You don’t need to take it all at face-value (just be picky in terms of what inspires you, and discard the rest). Now let’s move on:

1. On giving meaning to the world through photographs

Cartier-Bresson wasn’t interested at all in “staged photography” – he was only interested in capturing candid and un-posed photographs.

Personally I don’t think a “candid” photograph is necessarily better than a photograph with either implicit or explicit permission from a subject. In-fact, Cartier-Bresson shot a lot of portraits of artists, friends, and famous people in his life– and all of those people were aware that Cartier-Bresson was photographing them.

Anyways, this is what Cartier-Bresson had to say about “manufactured” or “staged” photography:

“’Manufactured’ or staged photography does not concern me. And if I make a judgment it can only be on a psychological or sociological level. There are those who take photographs arranged beforehand and those who go out to discover the image and seize it.”

Cartier-Bresson continues by explaining what the camera means to him:

“For me the camera is a sketchbook, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity, the master of the instant which, in visual terms, questions and decides simultaneously.”

You can see how Cartier-Bresson uses the analogy of the camera being a “sketchbook” – and how important intuition and spontaneity is in terms of clicking the shutter.

Furthermore, Cartier-Bresson is interested in using photography as a way of constructing meaning out of the world (with his camera):

“In order to “give a meaning” to the world, one has to feel oneself involved in what one frames through the viewfinder. This attitude requires concentration, a discipline of mind, sensitivity, and a sense of geometry– it is by great economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression. One must always take photographs with the greatest respect for the subject and for oneself.”

There are several points, which I find fascinating with this excerpt from Cartier-Bresson.

a) “In order to ‘give a meaning’ to the world, one has to feel oneself involved in what one frames through the viewfinder”

Cartier-Bresson espouses the importance of being emotionally or personally involved in the photography one does. You can’t just be an outside observer, you are more of an active participant.

b) “This attitude requires concentration, a discipline of mind, sensitivity, and a sense of geometry”

To capture meaning in the world, you can’t get distracted (only focus on shooting, don’t think about anything else), having the discipline to capture a great moment, sensitivity (being emotionally empathetic towards your subject), and a sense of geometry (composing your photograph well, by framing it well, and having compositional elements which complement your subject).

c) “It is by great economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression”

I like this quite Zen-like philosophy of “simplicity of expression” – that great photographs don’t need to be complicated– they should be distilled to say the most in a photograph without being overly complex. Most of Cartier-Bresson’s finest images are quite simple and minimalist geometrically speaking, whereas photographers such as Alex Webb tend to be “maximalists”).

d) “One must always take photographs with the greatest respect for the subject and for oneself.”

Photography as being a two-way street, an interaction between the subject and photographer. You need to shoot from the heart, and try to understand your subject – and know there is a strong, almost spiritual connection between you and who is on the other side of the viewfinder.

Takeaway point:

I think one of the most important questions to ask yourself as a photographer is: “Why do I shoot? And what is it about street photography which appeals to me the most? Why do I shoot ‘street photography’? What does it do for me on a personal basis? How does it change how I see and interact with the world? Does street photography make me a better person– if so, how? What makes my photography unique from other street photographers, or other photographers in general?”

Cartier-Bresson was quite clear why he shot photography: he wanted to give meaning to his world.

I think the way he also constructed his emotions were two-fold: trying to capture emotion and empathy for his subjects, while also composing them in a geometrically beautiful way. Generally I think Cartier-Bresson was more biased towards making beautiful images (some of his images lack emotion, but are composed really well). Not to say that Cartier-Bresson’s photographs lack emotion and empathy– he has captured many emotional images (which I think tend to be his best work).

Regardless, I think Cartier-Bresson is definitely onto something. As photographers and human beings, we are constantly trying to construct meaning in our lives and in the world. And I think street photography is one of the most beautiful vehicles to better explore, interact, dissect, and understand the world through image making.

2. On the joy of photography

I think sometimes we get too focused on making great images, getting lots of followers and likes on social media– that we forget the inherent joy of photography.

Cartier-Bresson in 1976 wrote this about the joy of photography:

“To take photographs is to hold one’s breath when all faculties converge in the face of fleeting reality. It is at that moment that mastering an image becomes a great physical and intellectual joy.”

I love this quote for so many different reasons.

First of all, literally writing that photography is to hold one’s breath makes it so much more vivid– and alive. I sometimes get quite nervous when I am shooting street photography– but it is in those moments that I totally lose a sense of myself, and totally get enveloped in “the moment” or “the zone” (similar to being in a “flow state” as psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes). If you want to learn more about “flow”, I recommend reading his book: “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience“.

Also Cartier-Bresson says that when taking photographs, the key moment is when “all faculties converge in the face of fleeting reality” – meaning that all of his senses become heightened (his vision, his reflexes, etc.) when he sees reality (what he sees before him) going away before his very eyes (fleeting). As photographers, that is what we are trying to do– capture reality before it fades before our very eyes. Especially in street photography– where moments come and go quite quickly, and are fleeting in nature.

And one of the great joys that Cartier-Bresson gains in trying to capture these “fleeting moments” and using all of his skills with the camera, composition, and timing his images (that he feels great physical and intellectual joy).

I think Cartier-Bresson brings up a great point: that photography (especially street photography) incorporating both the physical and intellectual joy.

- The physical: Running around on the streets, being physically quick to capture moments, being physically adept with your camera (knowing how to focus quickly, change your aperture, shutter speed, ISO, etc.), and framing your camera with ease.

- The intellectual: Using your brain when shooting, knowing how to frame your photograph, how to incorporate graphical and geometrical shapes and balance in your image.

A lot of psychology I have been studying stresses the importance of having a good balance between the physical/mental in our life. When our bodies are physically well and thriving, we tend to do better mentally. And vice-versa: when we are mentally well and happy, our bodies tend to be physically better as well.

Takeaway point:

In street photography, if you want to heighten your experience and the joy you get out of it– try to see how you can combine both the physical and mental in the streets.

- The physical: make sure you practice your timing in street photography. Try to be faster when it comes to shooting. Don’t hesitate. Approach strangers and interact with them when you feel your heart pounding and you are nervous. Also get so trapped in the “flow” of the streets– that you loose yourself physically. Don’t do the walking– let your feet do the walking, and over time the more skilled you get in street photography, your camera will shoot itself (without your mind thinking).

- The mental: Try to really get into a meditative state when you’re shooting in the streets. You can do this by turning of your smartphone, turning it to airplane mode, or muting it. Don’t let any external things distract you. I know some street photographers who like to listen to music to “zone out” – personally I don’t like doing this as it makes me lose focus from the streets. But if this works for you– go for it.

Furthermore, make sure when you’re shooting your mind is actively composing the scene– looking at the edges of the frame, and being intellectually challenged and stimulated. If you shoot mostly single-subjects walking by billboards or posters (and are bored by that)– try to capture more layers, nuances, and depth in your photographs. Study Alex Webb, Garry Winogrand, and Nikos Economopoulos for more complex compositions and images.

Ultimately what you want when you’re shooting in the streets is to fall into a “flow state” – when you are 100% focused at the task at hand, when you lose a sense of time, and a loss of “self”. It will almost become like an out-of-body experience. I often find this when I disappear into the waves of people in New York City or London, or even when I am writing for this blog.

Seek these “flow states” – and lose yourself in the moment of shooting in the streets.

To learn more about “flow” and street photography, I recommend reading these articles:

- On Going with the “Flow” in Street Photography

- How to Embrace “Stream-of-Consciousness” in Street Photography

3. On capturing the “decisive moment”

“There is nothing in this world without a decisive moment.” – Cardinal Retz

I think one of the best ways to describe street photography is to capture “decisive moments” (or Kodak moments).

I also am quite aware that the use of the “decisive moment” in street photography is a bit over-used and cliché. But at the same time, I don’t think there is a better term to describe the importance of both recognizing a great image/moment and having the intuition and skill to capture it quickly.

This is what Cartier-Bresson said about capturing “the decisive moment”:

“To take photographs means to recognize– simultaneously and within a fraction of a second– both the fact itself and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that gives it meaning. It is putting one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis.” – 1976

I wrote in an article titled: “The Myth of the Decisive Moment” that the recognition of great images and when to hit the shutter varies (even within a scene). Meaning, if you see a great scene (which you think you can get a great street photograph)– don’t just take one image. Work the scene. Take lots of images (as Cartier-Bresson did if you inspect his contact sheets).

But I think we shouldn’t misconstrue Cartier-Bresson’s exact words. I think people (including myself) misinterpret what Cartier-Bresson said and intended. To be more clear about “the decisive moment” – let’s try to break it down together below:

a) “To take photographs means to recognize– simultaneously and within a fraction of a second– both the fact itself and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that give it meaning.”

Cartier-Bresson tells the importance of recognition of “the fact itself” (the subject matter) and “rigorous organization of perceived forms” (composition), “that give it meaning” (what emotion/meaning/message are you trying to get through a photograph). Therefore I think the decisive moment includes 3 key elements:

- Identifying a great moment or potential photograph

- Composition

- Emotion/meaning/message

Let’s break this down a little further below:

1. Identifying a great moment or potential photograph

To identify a great moment or potential photograph is to study a lot of great photography, and to study the masters. It is to study a lot of great photography books (mostly artist books) and to know what makes a great image– by seeing the great work that has been done before us, and by ingesting lots of great photographs into our visual vocabulary. It is also studying outside fields in art: painting, sculpture, film, drawings, and even music to inspire our work.

2. Composition

To make a great composition is to study composition itself. If you want to learn more about composition and street photography, I have done an entire series on it.

But composition in street photography is to use framing, leading lines, and contrast to best highlight your subject, and to separate them from the background. Composition is like little arrows that point at your subject and tell your viewer: “hey, look here” – while composition also serves to add balance, rhythm, and visual harmony and beauty to an image.

3. Emotion/meaning/message

Ultimately I think a photograph without emotion, meaning, or a message is a dead photograph. Who cares about a photo of anything– unless we are able to construct some sort of meaning, emotion, or message from it? Often I see a lot of street photography that is composed well and has a nice “moment”– but doesn’t say anything to me, or strike an emotional chord for me.

So when you are editing your street photographs (choosing your best images) ask yourself: “What am I trying to say with this photograph? What does this photograph mean to me? What emotions come forth in this image?”

So to sum up, you need these 3 things to create a strong “decisive moment”.

b) “It is putting one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis.”

Cartier-Bresson sums up very eloquently that creating a great “decisive moment” in photography is to combine your head (intellectual abilities), your eye (vision), and heart (emotions) on the “same axis”.

You need to be attuned to all of these aspects of photography: the intellectual, the visual, and the emotional to create a memorable and meaningful photograph.

Takeaway point:

Street photography wouldn’t exist without “decisive moments” — gestures, facial expressions, motions, and any of life’s moments. Find these decisive moments by always having you camera ready (with you), and with your heart ready and open to capture them.

3. Why take photos?

We discussed this a bit earlier in point #1, but Cartier-Bresson expands on what photography means to him– ultimately visual expression:

“As far as I am concerned, taking photographs is a means of understanding which cannot be separated from other means of visual expression. It is a way of shouting, of freeing oneself, not of proving or asserting one’s originality. It is a way of life.”- 1976

Cartier-Bresson also tells us what photography and visual expression isn’t about– which is “proving or asserting one’s originality”.

Rather, Cartier-Bresson just tell us photography is simply “a way of life”.

I have to agree with Cartier-Bresson on this point: I think street photography isn’t just wandering the streets and making images. It is a way of life– it is a lifestyle and an approach to the way we see and interact with the world.

For example, street photography has helped me become a better human being in many different ways:

a) Street photography has helped me become more empathetic

I feel that through shooting photos of strangers, I can become more empathetic to their situation. I can feel their heart, their emotions, and I try to capture these feelings through my camera. I become more attuned to individuals around me, whereas I used to be caught up in my own bubble and world.

b) Street photography has helped me become more attuned to life

Nowadays with my smartphone and technology, I am always distracted. I am always in a daze. From the moment I wake up, and to the moment I sleep– I am distracted (and eyes glues to my smartphone more than I would like). Even when I am eating I catch myself reading books or articles on my phone, or listening to music or podcasts. I need constant stimulation, and never do just one thing at a time.

But with street photography, I have no other distractions. I just focus on shooting. I don’t listen to music, and have any other external forms of distractions. Street photography is one of the few times in my everyday life and existence when I just tune out from the bullshit of everyday life– financial stress, stress about my relationships and family, stress about how others perceive me, and the stress I get about the purpose of my everyday life and existence.

c) Street photography forces me outside of my comfort zone

Street photography at times still can be terrifying to me. I still miss dozens of great “decisive moments” because I am too nervous to bring up my camera, or afraid of pissing somebody off.

However street photography has helped me become a more confident person. I used to never have the courage to take a photo of a stranger before street photography– but now it has become much easier.

I also used to never talk to strangers before street photography. But street photography has helped me approach strangers I would have never had the confidence before to do so. And also small things: I have no problem approaching strangers and asking for help, directions, or questions.

Street photography has also helped me be more assertive and confident when I am in a room full of strangers. If I have the confidence to take a photo of a stranger with (or without) permission– I can interact with a group of strangers. I used to have (somewhat) severe stage fright and would tense up, stutter my words, and my heart rate would go dramatically up when speaking before a large crowd. But that has mostly disappeared after being a more confident street photographer.

d) Street photography has helped me appreciate the small things of everyday life

I think street photography can also be well described as “capturing the beauty in the mundane”. It is capturing the beauty of everyday things, and everyday ordinary moments.

I was initially drawn to street photography because I didn’t need crazy events happening– like thunderstorms or double-rainbows to make interesting photographs. The world was my oyster– I could just go explore by leaving my apartment, walk around my neighborhood– and experience life in the small things.

I now take great pleasure in noticing (and photographing) the small joys of everyday life: seeing an old couple (still in life) holding hands and talking at a cafe, a little child smiling at his/her parent, or a cat enjoying a nice walk in the park.

All of this was totally hidden to me before I started shooting street photography.

Takeaway point:

Street photography isn’t just about making photos in the streets– it an attitude, and a way of life. See how you can see your street photography as how you interact with strangers, how you appreciate the small things in life, and live life more vividly.

4. On Buddhism

As I mentioned earlier in the introduction of this article that many people have claimed that Cartier-Bresson was a “stealth Buddhist”. In-fact, it mentions the link between Cartier-Bresson and Buddhism on the front-cover of “The Mind’s Eye”.

So what does Cartier-Bresson himself think about Buddhism? He explains his thoughts below:

“Buddhism is neither a religion nor a philosophy, but a medium that consists in controlling the spirit in order to attain harmony and, through compassion, to offer it to others.” – 1976

I have personally been influenced highly by Buddhism (although I am Catholic by religion and birth). I have learned a lot from Buddhism in terms of finding more peace, harmony, and compassion in my everyday life. It has helped relieve a lot of the “mental suffering” that I experience in my everyday life.

Cartier-Bresson says that Buddhism isn’t a religion nor a philosophy (so don’t worry if others judge you as being “new-agey” when you are interested in Buddhism) and how it is a medium that “consists in controlling the spirit to attain harmony”.

I think a lot of live “un-harmonious” lives in the sense that we feel discomfort, dissatisfaction, and edginess in our everyday lives. We feel dissatisfied with what we currently own (let’s say our cameras and equipment, our cars, our homes), we feel dissatisfied with our relationships with others, and we sometimes feel dissatisfied with our jobs and what we are doing with our lives.

However I found that street photography is one of the best ways to gain more appreciation in our everyday lives– it helps us achieve harmony in our lives in the sense that it brings joy to our lives, and helps us focus on the present moment (without lamenting about the past, or feeling anxious about the future).

Furthermore, Cartier-Bresson saw Buddhism as a way of offering harmony to others, through compassion.

I also feel that is another gift of street photography: you are capturing beautiful (and sometimes not so beautiful) moments of everyday life– and offering it to others. I think your street photographs can help inspire your viewers to be more attuned to everyday life, to appreciate life, and also to find more happiness. And through shooting street photography in a compassionate way– we can achieve this.

Takeaway point:

So remember, you are doing a good thing through street photography. You are contributing to others in society. You are capturing beautiful “decisive moments” of everyday life, which can sometimes relieve the suffering of your viewers, by making them appreciate the small things.

Let’s say you shoot a street photograph, show it to someone, and it makes them laugh or smile. Congratulations– you just made their day much happier and upbeat. You have made the world a slightly better place (by influencing that one person).

Let’s say you shoot a street photograph that is a little more depressing or sad. Then you show it to someone– and it deeply touches or moves him or her emotionally. You get your viewer to empathize with the subject in your photograph. Congratulations– you have given your viewer the opportunity to be more empathetic to the suffering of others through your photograph. You have made the world a slightly better place.

Through street photography you are making the world a better place– one image at a time, and by influencing one person at a time.

5. On the passion for photography

As mentioned earlier, Cartier-Bresson wasn’t so interested in photography “in itself”– but rather, capturing emotion and beauty in the world:

“My passion has never been for photography ”in itself,“ but for the possibility– through forgetting yourself– of recording in a fraction of a second the emotion of the subject, and the beauty of the form; that is, a geometry awakened by what’s offered. The photographic shot is one of my sketchpads.” – 1994

Street photography isn’t the only way of “forgetting yourself” or capturing emotions of your subjects, or the beauty of the forms in the world.

Other artists can do this via sketching, via making movies, via making sculptures, via writing, and via painting.

However as street photographers, we choose to capture beauty in the world with our cameras. Perhaps we aren’t so good at drawing or sketching– so we use our cameras instead.

Takeaway point:

I think sometimes we lose inspiration for street photography. But at the end of the day, you don’t need to be interested in photography. You just need to interested in life, and curious about the beauty in the world.

I know a lot of street photographers who don’t shoot street photography anymore. While part of me feels like that is a shame– they have gone onto doing different and sometimes better things. Some have picked up painting, some have picked up writing, and some have picked up music. They have found other ways to express themselves, and the beauty of the world they experience around them.

So if street photography no longer interests you, or you no longer have a passion for it– perhaps it is healthy to take a break from it, and see if it is truly the best way for you to express yourself.

Even Cartier-Bresson did this at the end of his career and life: he gave up photography and decided that painting and drawing was a better way he could express himself and the beauty of the world around him.

For me personally, I gain a lot of the meaning I experience in the world through reading, writing, and teaching. Taking photographs is just one of the very many ways I create meaning in my world.

So don’t feel photography needs to be the only way you can more vividly experience the world– it is just another tool.

6. Cartier-Bresson’s personal history in photography

In “The Mind’s Eye” Cartier-Bresson talks a little about how he got started in photography– and his personal background and story. He first starts off by sharing how he picked up photography as a small boy:

Picking up photography as a small boy

“I, like many another boy, burst into the world of photography with a Box Brownie, which I used for taking holiday snapshots. Even as a child, I had a passion for painting, which I ”did“ on Thursdays and Sundays, the days when French school children don’t have to go to school. Gradually, I set myself to try to discover the various ways in which I could play with a camera. From the moment that I began to use the camera and to think about it, however, there was an end to holiday snaps and silly pictures of my friends. I became serious. I was on the scent of something, and I was busy smelling it out.”

You can see Cartier-Bresson’s first foray into photography– when he started off not taking it too seriously– just taking holiday snapshots (like many of us). We also learn that Cartier-Bresson had a passion for painting as a small child (he did this on his own, as he didn’t have to do it while at school).

Furthermore, you see how he started exploring the possibilities of working with a camera– as he went out to “discover the various ways which I could play with the camera.”

However he soon discovered that he wanted to become more serious with his camera– and like a bloodhound, he started to detect the scent of the possibility of photography– and became dedicated to pursuing it and “sniffing it out”.

Early inspiration from films

Cartier-Bresson also got a lot of inspiration early on from films. He explains:

“Then there were the movies. From some of the great films, I learned to look, and to see. ”Mysteries of New York”, with Pearl White; the great films of D.W. Griffith– ”Broken Blossoms“; the first films of Stroheim; ”Greed“; Einstein’s ”Potemkin“ and Dreyer’s ”Jeanne d’Arc”–these were some of the things that impressed me deeply.

Cartier-Bresson describes that seeing films early-on helped him to “look, and to see.”

I think these are very important aspects– to be curious in terms of looking at visual forms. To be excited by what the camera can do. The there is the second part: learning how to see (seeing the possibilities of what a camera could achieve).

This takes us back to an important part of photography in general: learning how to see with your eyes, knowing what interests you, and being curious is much more important than what camera you shoot with or being technically proficient in photography.

Going to Africa

Cartier-Bresson also embarked on an epic trip to Africa (at the ripe age of 22). He tells us his journey below:

“In 1931, when I was 22, I went to Africa. On the Ivory Coast I bought a miniature camera of a kind I have never seen before or since, made by the French firm Krauss. It used film of a size that 35mm would be without the sprocket holes. For a year I took pictures with it. On my return to France I had my pictures developed– it was not possible before, for I lived in the bush, isolated, during most of that year– and I discovered that the damp had got into the camera and that all my photographs were embellished with the superimposed patterns of giant ferns.”

Every photographer’s nightmare happened to Cartier-Bresson as a young man: after shooting for a year in an exotic and remote place in the world, he discovered all of his film was ruined.

However he didn’t let this huge setback disappoint him or prevent him from being curious in photography. Rather, it was almost like a fire, which made him even more curious and passionate about photography.

Discovering the Leica and trapping life

Cartier-Bresson then continues by sharing how he discovered the Leica, which liberated him (being a small, easy-to-use camera) to hunt moments in the street and pursue “trapping life”:

“I had blackwater fever in Africa, and was now obliged to convalesce. I went to Marseille. A small allowance enabled me to get along, and I worked with enjoyment. I had just discovered the Leica. It became the extension of my eye, and I have never been separated from it since I found it. I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to “trap” life– to preserve life in the act of living.”

Although now we look at the Leica as an expensive, luxury item for only rich people– it was revolutionary when it was first invented. It was the world’s first 35mm camera. It was the first truly compact and usable camera both for amateurs and working professionals. Before the Leica, most photographers used bulky and clunky large-format or medium-format cameras. Cartier-Bresson found the small Leica to free himself to prowl the streets all day, and to “preserve life in the act of living.” Photography was a way for Cartier-Bresson to augment his experience in living life– by capturing life and making it more vivid, and experiencing it more vividly.

Cartier-Bresson continues what he wanted to do with photography:

“Above all, I craved to size, in the confines of one single photograph, the whole essence of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.”

Obviously Cartier-Bresson was fascinated and marveled by life in general. He would see these amazing situations unfold before his very eyes– and would want to capture the “essence of some situation” with his camera. He wanted to make these moments eternal.

Personally I have a fear of forgetting– and photography is a way for me to record and document my everyday life through those around me. Photography helps me capture the happy moments of my life, and also some of the more depressing and lonely times. Photography is a vehicle for me to better capture, understand, and experience the world around me.

Takeaway point:

Cartier-Bresson’s start into photography was separated in these phases:

- Curiosity (discovering the art of photography)

- Pursuit and adventure (going to Africa)

- Frustration (discovering all his photos from Africa were ruined)

- Increased passion (buying a Leica and pursuing moments on the streets)

- Realization of the great potential of photography (self-actualization of his passion for life, for capturing fleeting moments)

Think about your own personal life journey in photography. How did you discover photography? How did you discover “street photography”? What about street photography first appealed to you? What made street photography unique from other types of photography out there? What are some of the personal challenges you had when you started street photography?

What are some challenges you still face today? And ultimately– what does street photography ultimately do for you? What joy or pleasure does it bring to your life? How has street photography helped you discover how you see and experience the world, and life in general?

Meditate upon these questions– and it will help you find more focus and direction in your photography (and perhaps life).

7. On being an amateur

Often when you hear the phrase “amateur” – you think of a newbie. Someone who is obviously clueless, an idiot, and unskilled.

When we hear someone is an “amateur” in photography– we presume that they are unskilled with a camera, don’t know the difference between aperture and shutter speed, that they don’t know the difference between a good and a bad photograph, and that they are totally clueless.

However I think this line of thinking is wrong: an amateur is merely someone who does something for the love of it. In-fact, the root word for “amateur” is love.

Cartier-Bresson says how after 25+ years of photography, he still sees himself as an amateur:

“25 years have passed since I started to look through my view-finder. But I regard myself still as an amateur, though I am still no longer a dilettante.”

So what is the difference between an “amateur” and a “dilettante”?

An amateur is someone who does something for the love of it, whereas a “dilettante” is a person who is interested in something “…without real commitment or knowledge” (according to Google).

So therefore Cartier-Bresson said in other words: I am still passionate and shoot photography because I love it, but I am not like other “amateurs” in the sense that I am truly committed to it and I now knowledgeable about photography.

Takeaway point:

I think we should be like Cartier-Bresson: we should be amateurs (without being dilettantes).

We should shoot for the pure joy and love of it, but at the same time– dedicate ourselves to truly committing ourselves to photography and learning more knowledge about photography:

- Shooting as an amateur is to shoot without any incentive of profit or money. It is self-mediated and intrinsic motivation (not extrinsic). And furthermore, we shoot for the sake of shooting.

- Furthermore, we commit ourselves to photography. We spend lots of time to shoot, we think about it, we immerse ourselves in it, we make photography a way of life.

- Lastly, we try to gain knowledge about photography and take it seriously. We educate ourselves by studying the work of the masters, buying books (and not gear), investing in photography classes and workshops, traveling and getting outside of our comfort zones, and surrounding ourselves with other photographers we admire and respect who give us constructive criticism to push our photography to the next level.

8. On creating a “picture story” or “photo essay”

I think one of the weaknesses of “street photography” is that it often too focused on the single image. We don’t focus as much on narrative and story telling (as reportage or documentary photographers do).

Cartier-Bresson talks about “photographic reportage” or a “picture story” below (note this is when magazines like “LIFE magazine” were the few and only ways a photographer could get published and have his/her work widely seen by the public).

He first starts off by saying that sometimes a single image can be so powerful– that a single image can be “a whole story in itself”:

“What actually is a photographic reportage, a picture story? Sometimes there is one unique picture whose composition possesses such vigor and richness, and whose content so radiates outward from it, that this single picture is a whole story in itself.”

However Cartier-Bresson makes the point that it is very rare that a single image can capture an entire story– and sometimes you need to build upon it and make a “picture story”:

“But this rarely happens. The elements which, together, can strike sparks from a subject, are often scattered– either in terms of space or time– and bringing them together by force is ”stage management,“ and, I feel, contrived. But if it is possible to make pictures of the ”core“ as well as the struck-off sparks of the subject, this is a picture-story. The page serves to reunite the complementary elements which are dispersed throughout several photographs.”

So Cartier-Bresson shares how a picture story can be told with several images– in terms of how you tell the core of a story with complementary images, and a lot of this is how images are laid out and sequenced.

He continues when you make a “picture story” – you must depict the content (in terms of what is actually happening in the photographs), but also making it emotional:

“The picture-story involves a joint operation of the brain, the eye, and the heart. The objective of this joint operation is to depict the content of some event which is in the process of unfolding, and to communicate impressions.”

Cartier-Bresson also shares the challenges of documenting a certain story or event– and how there are no “rules” or pre-established patterns you must follow:

“Sometimes a single event can be so rich in itself and its facets that it is necessary to move all around it in your search for the solution to the problems it poses– for the world is movement, and you cannot be stationary in your attitude toward something that is moving. Sometimes you light upon the picture in seconds; it might also require hours or days. But there is no standard plan, no pattern from which to work. You must be on the alert with the brain, the eye, the heart, and have a suppleness of body.”

Takeaway point:

I think as photographers in the 21st century– many of us started off with digital cameras and social media. We assume that photography is just about making strong single images and uploading them to Flickr, Instagram, or Facebook and getting lots of “likes”, “favorites” and comments (and gaining more followers).

However more sophisticated photographers aim to create bodies of work– they aim to create books, series, and projects (to learn more about how to work on a photography book or project, I recommend reading my article on “Photographer’s Sketchbooks” and “The Photobook: A History Volume III”).

So in short, aim to create “picture stories” – narratives, and series.

I have found one of the best ways to see how you can put together a “picture story” is look at the old LIFE magazines– and see how photographers were able to tell a story in 5–7 images. Look at how the images were laid out, sequenced, and how they complemented the text. See if there are any captions which add context to the images.

Furthermore, look at photographic books. See how many images there are in the book. See how the images are sequenced. Try to analyze the images (if they are paired together, side-by-side). Why did a photographer choose to create a certain sequence, and why did he decide to leave certain pages blank, while other pages pair together with other photographs?

Also watch films: they are probably the best way to understand opening shots, close-up shots, how to build up action in the film, what the climax is, and how to end a story. Or read books, literature, or fiction.

Some also find great inspiration in music– in terms of finding a cadence, flow, and rhythm.

9. Eliminate and subtract

One of the philosophies that Cartier-Bresson encourages is minimalism: to be able to eliminate and subtract from life. He explains his advice for photographers:

“Things-As-They-Are offer such an abundance of material that a photographer must guard against the temptation of trying to do everything. It is essential to cut from the raw material of life– to cut and cut, but to cut with discrimination.”

When I first started shooting street photography, I was also tempted in terms of “trying to do everything”. I tried to shoot weddings, children, landscapes, macros, etc. But it was when I finally discovered “street photography” and decided to focus, is when I started to really find purpose and meaning in my photography.

I also love how Cartier-Bresson shares the importance of “cutting from the raw material of life” (but cutting with discrimination).

It makes me think of the quote from Albert Einstein in which he says we should aim to make things as simple as possible (but not too simple).

After all, photography is more about subtraction (than addition).

Furthermore, he encourages us to “work the scene” if we smell the possible scent that it might be a great photograph. But we need to balance between being like a machine-gunner, and being discerning:

“While working, a photographer must reach a precise awareness of what he is trying to do. Sometimes you have the feeling that you have already taken the strongest possible picture of a particular situation or scene; nevertheless, you find yourself compulsively shooting, because you cannot be sure in advance exactly how the situation, the scene, is going to unfold. You must stay with the scene, just in case the elements of the situation shoot off from the core again. At the same time, it’s essential to avoid shooting like a machine-gunner and burdening yourself with useless recordings which clutter your memory and spoil the exactness of the reportage as a whole.”

Cartier-Bresson also shares the importance of elimination and subtraction when it comes to the editing phase (selecting your best work):

“For photographers, there are two kinds of selection to be made, and either of them can lead to eventual regrets. There is the selection we make when we look through the viewfinder at the subject; and there is the one we make after the films have been developed and printed. After developing and printing, you must go about separating the pictures which, though they are all right, aren’t the strongest.”

Cartier-Bresson also shares the importance of learning from our failures in our photographs. Did our photos fail because we hesitated while we were shooting? Or did we not see that we had a cluttered background? Or did we not see that we missed out some other information that was happening in the scene (that we should have included)? Or perhaps we got sloppy at some point when constructing the image? He elaborates below:

“When it’s too late, then you know with a terrible clarity exactly where you failed; and at this point you often recall the telltale feeling you had while you were actually making the pictures. Was it a feeling of hesitation due to uncertainty? Was it because of some physical gulf between yourself and the unfolding event? Was it simply that you did not take into account a certain detail in relation to the whole setup? Or was it (and this is more frequent) that your glance became vague, your eye wandered off?”

Takeaway point:

As photographers, there are two main ways we need to subtract:

- Shooting phase: we need to subtract clutter and unnecessary elements while shooting.

- Editing phase: we need to subtract the weak photos during the editing phase.

Both are absolutely crucial.

1. Shooting phase:

When we are in the shooting phase, we should try to be discerning while we are shooting. We should try to “work the scene” by taking multiple images, from the side, by crouching, or sometimes by standing on our tippy-toes. We should wait for other interesting gestures to happen, and decide to click at those moments. We shouldn’t also leave the scene too early and stop shooting– but at the same time, not add too much clutter by wasting frames by shooting too much.

We should also try to subtract clutter from the background. Try to avoid random cars, trees, white bags, or other distractions that might take away from the scene.

Try to also eliminate subject matter that might distract from the scene (other subjects in the frame that aren’t as important).

2. Editing phase:

The editing phase is one of the most difficult times to subtract. We become emotionally attached to our photographs, as we often have vivid memories of having taken certain shots, and the interesting backstories we have.

But just because your photo might have an interesting backstory doesn’t mean that it will make an interesting photograph. Often backstories (or having really long and detailed captions) are just a blanket for the fact that the photograph itself isn’t strong (and it needs a backstory or a caption to “explain” it). I think a strong image should stand on its own and require no additional support.

We also need to be better at learning how to “kill our babies” when it comes to working on a body of work or a project. For example, if you are working on a series and you have a certain image that doesn’t fit the narrative (but might be a strong single-image), you might have to edit it out (to benefit the story). For example, in Trent Parke’s “Minutes to midnight” apparently he had to edit out 3 of his favorite images, because they didn’t fit the narrative of his book.

I think in photography, you are only as good as your weakest image. Take out the weak links in your work, and let the strong work speak.

10. On vanishing things

One of the biggest gifts of street photography (and also the biggest curses) is that things are constantly vanishing. Once a moment has come and gone, it is lost forever.

The upside is that when you shoot street photography, nobody will be able to shoot that certain photograph (like how you shot it). But the downside is that if you’re not quick enough to capture “the decisive moment” – you will never be able to capture it again.

Cartier-Bresson explains this below– how we as photographers constantly deal with the transient and vanishing:

“Of all the means of expression, photography is the only one that fixes forever the precise and transitory instant. We photographers deal in things that are continually vanishing, and when they have vanished, there is no contrivance on earth that can make them come back again.”

Furthermore, Cartier-Bresson brings up the idea of memories– how we cannot develop and print them (simply from our own heads). The upside of being a writer or a painter is that they have the time to sit, meditate, and create (from their own minds) what they want to.

However as photographers, we can only deal with the transient– the things that we see before our very own eyes (that will disappear quickly):

“We cannot develop and print a memory. The writer has time to reflect. He can accept and reject, accept again; and before committing his thought to paper he is able to tie the several relevant elements together. There is also a period when his brain ”forgets,“ and his subconscious works on classifying his thoughts. But for photographers, what has gone is gone forever.”

Cartier-Bresson also brings up the anxieties (and also strengths) this can bring to our work:

“From that fact stem the anxieties and strengths of our profession. We cannot do our story over again once we’ve got back to the hotel. Our task is to perceive reality, almost simultaneously recording it in the sketchbook which is our camera.”

Furthermore, Cartier-Bresson is tied to the idea that we should try to capture reality (as we see it) rather than trying to manipulate or misconstrue it:

“We must neither try to manipulate reality while we are shooting, nor manipulate the results in a darkroom. These tricks are patently discernible to those who have eyes to see.”

The difficult thing though is that when we are photographing, we are essentially interpreting reality in one-way or another. There is no “objective truth” or “objective reality” when we are photographing. But essentially what I think Cartier-Bresson is trying to tell us to be authentic– to present our own authentic version of reality through our images.

Takeaway point:

Realize that while fleeting moments can be a downside to photography (especially street photography)– it is also our strength.

I personally don’t think street photography would be as rewarding if it was too easy. It is the challenge that is the reward.

Also realize that you want to live life without regrets. I have regretted so many times not having taken a photograph out of hesitation or fear (worrying if someone might get angry at me, or worrying that the shot I take is boring and of no interest to others).

But ultimately you want to follow your gut. If you have even a minuscule feeling that a photograph might be a good one– just shoot it. You can always edit it out later.

Shoot without regrets, and live without regrets. Life is quickly vanishing before our very eyes– and if we don’t experience and capture it, it will be gone forever.

11. On interacting with people

Although Cartier-Bresson was more of a “stealth street photographer” (he didn’t like being noticed when shooting) – he interacted a lot of his subjects, especially when he shot formal portraits. But at the same time, he was very conscientious and aware of how he interacted with strangers (especially in foreign countries).

Cartier-Bresson writes about the importance of a photographer having a certain relationship with a subject:

“The profession depends so much upon the relations the photographer establishes with the people he’s photographing, that is a false relationship, a wrong word or attitude, can ruin everything. When the subject is in any way uneasy, the personality goes away where the camera can’t reach it.”

But how does a photographer make strong images, without being obtrusive or disrespectful towards his subjects? Cartier-Bresson admits there are no foolproof systems– and that we must treat each individual subject and situation differently– to be as unobtrusive as we can:

“There are no systems, for each case is individual and demands that we be unobtrusive, though we must be at close range. Reactions of people differ much from country to country, and from one social group to another. Throughout the whole of the Orient, for example, an impatient photographer– or one who is simply pressed for time– is subject to ridicule. If you have made yourself obvious, even just by getting your light-meter out, the only thing to do is to forget about photography for the moment, and accommodatingly allow the children who come rushing at you to cling to your knees like burrs.”

Takeaway point:

I think the best advice I have heard in street photography is from Bruce Gilden, “Shoot who you are.”

To expand on that– I think it is also important to shoot in a way that reflects your personality.

For example, if you find yourself more introverted and not liking to interact with strangers and “disturbing the scene” – stick to your guts and instinct, and shoot that way. Cartier-Bresson would like to shoot this way, as does Constantine Manos, Jeff Mermelstein, Alex Webb and many other more “candid behind-the-scenes” photographers.

However if you find yourself a type of street photographer who likes to interact with your subjects – follow that instinct. Be social, influence the scene, embed yourself into the scene. Be like Bruce Gilden, Garry Winogrand, William Klein– and show your personality through your work.

But at the end of the day– you want to be empathetic and loving towards your subjects. Treat your subjects how you would like to be treated.

If you generally like to be left alone and have your personal space, perhaps shoot street photography more from a distance (and more candidly). If you like interaction, perhaps you can ask your subjects for permission– or just shoot from a close and intimate distance.

Follow your heart, and do what feels right for you.

12. On knowing what to photograph

One of the challenges we have as photographers is knowing what to photograph. After all, the world is a big place– and subject matter out there is infinite.

Cartier-Bresson gives us some thoughts:

a) Photographing what we feel

First of all, Cartier-Bresson encourages us to photograph what we feel:

“There is subject in all that takes place in the world, as well as in our personal universe. We cannot negate subject. It is everywhere. So we must be lucid toward what is going on in the world, and honest about what we feel.”

We should focus on our own “personal universe” – and photograph subject matter which is personal and honest – in terms of what we feel and perceive reality.

b) Communicate reality

Cartier-Bresson also says that when you are photographing, you aren’t just documenting facts and “things as they are”. Rather, you are making an interpretation of your own world and reality:

“Subject does not consist of a collection of facts, for facts in themselves offer little interest. Through facts, however, we can reach an understanding of the laws that govern them, and be better able to select the essential ones which communicate reality.”

Therefore through the act of photography, you also better understand the world around you– and you want to select the “essential truths” which communicate reality from your perspective.

c) Great subjects often lie in the smallest things

Know that when you are selecting subjects to shoot in street photography, it is often the small details or the small events that make the best photographs:

“In photography, the smallest thing can be a great subject. The little, human detail can become a leitmotiv. We see and show the world around us, but it is an event itself which provokes the organic rhythm of forms.”

So realize that the best photography is often in your own backyard. I know– it is hard to make interesting photographs in our own neighborhood. It all seems so boring. We become conditioned and normalized to our environments.

But strive to break out of that self-imposed barrier. Imagine yourself to be a tourist in your own neighborhood or city. What would you find interesting? What would you find fascinating? What would seem weird or out-of-place? See things from an outside perspective, and make beautiful art.

Takeaway point:

Photograph what is personal, meaningful, and local to you.

You don’t need to venture off to Tokyo, Hong Kong, Kyoto, New York, or Paris to make interesting photographs.

Personally I have found whenever I photograph in foreign countries– I end up taking more touristy snapshots than meaningful and personal photographs.

I am currently doing a project in which I’m just shooting urban landscapes around my neighborhood. It is a personal project– and it is forcing me to see my own environment with fresh eyes. It is a bit frustrating and difficult at times– but ultimately rewarding.

13. On shooting portraits

In “The Mind’s Eye”, Cartier-Bresson also gave tons of great advice in terms of shooting portraits:

a) Capturing the environment around the subject

One of the big take-aways I gained from Cartier-Bresson is the importance of photographing the environment of your subject.

I often photograph people against blank walls– but I am starting to realize the importance of capturing “environmental portraits”– in which the background shows the personality of your subject (as much as the subject him/herself):

“If the photographer is to have a chance of achieving a true reflection of a person’s world– which is as much outside him as inside him– it is necessary that the subject of the portrait should be in a situation normal to him. We must respect the atmosphere which surrounds the human being, and integrate into the portrait the individual’s habitat– for man, no less than animals, has his habitat.”

b) Make the subject forget the camera

Another great tip from Cartier-Bresson: photograph long enough and be unobtrusive enough that your subject forgets that the camera is there. He suggests us to not use fancy equipment, which can be intimidating to your subject:

“Above all, the sitter must be made to forget about the camera and the photographer who is handling it. Complicated equipment and light reflectors and various other items of hardware are enough, to my mind, to prevent the birdie from coming out.”

So leave the tripod, lights, and reflectors at home (if you want to capture the “true essence” of your subject).

c) Capturing the expression of a human face

One of the biggest things that Cartier-Bresson is fascinated about (when it comes to shooting portraits) is the expression of the human face. But how do we capture good expressions of the human face?

Cartier-Bresson gives us advice: the first expression a person gives you is often the best one, and sometimes you should try to spend time and “live” with your subject– to figure out what the best expression of them is:

“What is there more fugitive and transitory than the expression on a human face? The first impression given by a particular face is often the right one; but the photographer should try always to substantiate the first impression by ”living“ with the person concerned.”

Also realize when you are shooting a portrait– there is a struggle: often subjects want to display themselves in the best light, but that isn’t often what the photographer wants:

“The decisive moment and psychology, no less than camera position, are the principal factors in the making of a good portrait. It seems to me it would be pretty difficult to be a portrait photographer for customers who order and pay since, apart from a Maecenas or two, they want to be flattered, and the result is no longer real. The sitter is suspicious of the objectivity of the camera, while the photographer is after an acute psychological study of the sitter.”

So realize when you are shooting portraits, your subject often has a vision of how he/she wants to be portrayed (usually in a flattering light). But you as a photographer need to make an acute psychological study of your subject– and try your best to convey who you think they are.

Of course at the end of the day, this will be very subjective– the way you interpret or view your subject isn’t the “objective” reality. But as a photographer, you are trying to create your own reality of the world– so stay true to your initial impressions and gut intuitions.

d) Every portrait you shoot is a self-portrait

Realize also when you are shooting portraits, the photos you take are also a reflection of yourself. Cartier-Bresson explains:

“It is true, too, that a certain identity is manifest in all the portraits taken by one photographer. The photographer is searching for identity of his sitter, and also trying to fulfill an expression of himself. The true portrait emphasizes neither the suave nor the grotesque, but reflects the personality.”

So generally when you look at the portraits of Cartier-Bresson, there is a feeling that they are natural, unforced, and quite calm and peaceful. It shows that when Cartier-Bresson is shooting portraits, he does it very respectfully and unobtrusively. I suppose this is how Cartier-Bresson would also have liked to have his own portrait taken.

e) Vulnerability in portraits

When shooting portraits, you also make your subjects open and vulnerable to you. And you yourself should make yourself vulnerable to your subject:

“If, in making a portrait, you hope to grasp the interior silence of a willing victim, it’s very difficult, but you must somehow position the camera between his shirt and his skin. Whereas with pencil drawing, it is up to the artist to have an interior silence.” – 1996

Takeaway point:

To shoot a portrait of someone which captures his/her “essence” is one of the most difficult things in photography.

As we are mostly street photographers, we will probably be most drawn to “street portraits” – in which we stop a stranger in the street, and ask permission to take a portrait of them. These “street portraits” often require you interact with your subjects– and sometimes have them pose for you in a certain way.

I don’t necessarily think that because a photo is with permission or posed makes it a worse photograph. If anything, it makes it much more open and loving– as you have to interact with your subject. To make your subject open up, you need to make yourself vulnerable to your subject as well.

Ultimately know when you are shooting a portrait of someone on the streets (or anybody)– there is no “objectivity” to the image. Your vision is your own– and realize your subject might not always like the photo you make of them.

So generally what I do is this: if I’m shooting digitally, I’ll show them on the LCD screen of the photo I made of them. I will ask them how they like the image (they generally do)– and I offer to email it to them. When I’m shooting film, I ask my subject if they have a smartphone (they usually do)– and I’ll use their iPhone to take a flattering portrait of them (which they can later use as their Facebook profile picture or something).

If you are interested in portraiture, I highly recommend you to read my article on Richard Avedon.

14. On composition

Now we have encountered a nice juicy section: on composition. Cartier-Bresson was famous for being absolutely passionate and fanatical about his compositions in his photography (as he started off initially interested in painting, and later moved onto photography).

So what does the big man have to say about composition? Let’s continue on in our journey and discover more from the master:

a) Communicating the subject via composition

So what does composition and form mean to Henri Cartier-Bresson?

First of all, one of Cartier-Bresson’s intent in composition is to “communicate the intensity” of the subject. Meaning, the purpose of composition is to best highlight the subject of a photograph:

“If a photograph is to communicate its subject in all its intensity, the relationship of form must be rigorously established. Photography implies the recognition of a rhythm in the world of real things. What the eye does is to find and focus on the particular subject within the mass of reality; what the camera does is simply to register upon film the decision made by the eye.

Furthermore, what composition should do is guide the eye to focus on a particular subject in a photograph. This means eliminating distractions – don’t photograph what might distract the viewer from your intended subject.

Cartier-Bresson continues in sharing the importance of composition: that composition should be done intentionally while you make an image– and that you cannot separate composition from the subject, and the photograph itself:

“We look at and perceive a photograph, as we do a painting, in its entirety and all in one glance. In a photograph, composition is the result of a simultaneous coalition, the organic coordination of elements seen by the eye. One does not add composition as though it were an afterthought superimposed on the basic subject material, since it is impossible to separate content from form. Composition must have its own inevitability about it.”

So when you are out shooting on the streets, don’t just shoot blindly and hope your compositions are good. Often I think beginner street photographers just look for interesting subjects and photograph them without any regard for the background or composition.

It is difficult, but try to incorporate composition and form while you are shooting. A great tip: look at the edges of the frame and the background while you are shooting. Don’t focus too much on the subject– this will help you make better compositions and improve your framing.

b) On capturing the right moment

Cartier-Bresson talks in photography, our subjects and the world is constantly moving. Life unfolds fluidly before our very eyes as he explains:

“In photography there is a new kind of plasticity, the product of instantaneous lines made by movements of the subject. We work in unison with movement as though it were a presentiment of the way in which life itself unfolds.”

But while the world around us is moving, there is one moment in which all of the elements come to balance and equilibrium. This is another reference to capturing a “decisive moment” (where everything comes together):

“But inside movement there is one moment at which the elements in motion are in balance. Photography must seize upon this moment and hold immobile the equilibrium of it.”

When capturing a “decisive moment” – realize that your subject and the world are in a constant flow of flux.

When you are out shooting on the streets, imagine slowing down every movement– frame-by-frame. Imagine the world as a stop-action film, and you can slow down the frame rate. Then within each frame, imagine a single photograph.

Then try to dissect the frames, try to identify what might be the most interesting frames, and click the shutter when you think all the elements of composition are in perfect unison.

c) On evaluating scenes and modifying perspectives

When it comes to composition– changing your perspective is key.

You must constantly analyze your scene, and as Cartier-Bresson says, “perpetually evaluate”.

Sometimes even changing your head “a fraction of a millimeter” can change your perspective– and draw out certain details. He explains:

“The photographer’s eye is perpetually evaluating. A photographer can bring coincidence of line simply by moving his head a fraction of a millimeter. He can modify perspectives by a slight bending of the knees. By placing the camera closer to or farther from the subject, he draws a detail– and it can be subordinated, or he can be tyrannized by it. But he composes a picture in very nearly the same amount of time it takes to click the shutter, at the speed of a reflex action.”

So when you are out shooting in the streets, don’t just shoot everything from the same perspective and angle. Try moving your head a little to the left, right, up, or down. Move your knees and your feet as well– crouch down low, or sometimes step on top of things. Know that getting closer and further from your subject or scene will also change the perspective and the composition.

Lastly, remember that you have to make your reflexes quite quick and tight when you’re shooting– to compose as quickly as you click the shutter.

d) On stalling before shooting

Cartier-Bresson also talks the importance of delay while you’re shooting and composing. Sometimes you setup your scene, you have the right composition– but your gut tells you that something is missing.

In those cases, Cartier-Bresson urges us to “wait for something to happen”. Then only when you feel that you see something interesting happen is when you click the shutter (either you see an interesting hand gesture, someone walks into the frame, your subject looks into the lens, or someone’s facial expression changes). He explains:

“Sometimes it happens that you stall, delay, wait for something to happen. Sometimes you have the feeling that here are all the makings of a picture– except for just one thing that seems to be missing. But what one thing? Perhaps someone suddenly walks into your range of view. You follow his progress through the viewfinder. You wait and wait, and then finally you press the button– and you depart with the feeling (though you don’t know why) that you’ve really got something.

Cartier-Bresson also shares that he traces his photographs, to analyze the compositions of his images– and he uses this as a way to confirm his gut intuitions about the geometry of the images he captured:

“Later, to substantiate this, you can take a print of this picture, trace it on the geometric figures which come up under analysis, and you’ll observe that, if the shutter was released at the decisive moment, you have instinctively fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would have been both formless and lifeless.”

Cartier-Bresson makes an important point: that a photograph is often “formless and lifeless” without having a strong geometric composition.

e) On intuition and composition

But how conscious can we be of composition while we are shooting? Cartier-Bresson says that we should always think about composition, but at the same time– compose intuitively:

“Composition must be one of our constant preoccupations, but at the moment of shooting it can stem only from our intuition, for we are out to capture the fugitive moment, and all the interrelationships involved are on the move.”

What compositional tools does Cartier-Bresson use? He applies the “Golden Rule” and strictly analyzes his images after he shoots them (to continue to improve his vision and compositions):

“In applying the Golden Rule, the only pair of compasses at the photographer’s disposal is his own pair of eyes. Any geometrical analysis, any reducing of the picture to a schema, can be done only (because of its very nature) after the photograph has been taken, developed, and printed– and then it can be used only for a post-mortem examination of the picture. I hope we will never see the day when photo shops sell little schema grills to clamp onto our viewfinders; and the Golden Rule will never be found etched on our ground glass.”

So what is the “Golden Rule”? A quick Wikipedia search will show you that it is a compositional tool that painters and artists have used for thousands of years– having a precise balance and frame in images. To learn more about the “Golden Rule” within photography– I highly recommend checking out the blog of Adam Marelli (the best online resource when it comes to composition and photography).

While you’re out shooting on the streets, always have composition in the back of your mind. But know that you can’t be too analytical when you’re shooting on the streets– you won’t just see red lines of the “Golden Rule” in your viewfinder.

Rather, my suggestion is this: look at lots of great photography (with great compositions) like the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, and with enough viewing– your composition will become intuitive.

f) On cropping

Henri Cartier-Bresson is famous for being “anti-cropping” (although ironically enough, one of his most famous images of the guy jumping over the puddle is cropped). HCB’s excuse was that there was nothing he could do, as he was shooting through a hole in a fence.

Regardless, I think following Cartier-Bresson’s rule of not cropping is a good one. I personally haven’t cropped any of my images the last 3 years, and I have found that it has forced me to be more anal and stringent of composing my images.

When I used to crop a lot, I would be sloppy when it came to framing– because I always told myself, “Eh– I don’t need to get the framing right, I can always crop it later.”

However this is what HCB has to say about cropping:

“If you start cutting or cropping a good photograph, it means death to the geometrically correct interplay of proportions. Besides, it very rarely happens that a photograph which was feebly composed can be saved by reconstruction of its composition under the darkroom’s enlarger; the integrity of vision is no longer there. There is a lot of talk about camera angles; but the only valid angles in existence are the angles of the geometry of composition and not the ones fabricated by the photographer who falls flat on his stomach or performs other antics to procure his effects.”

Cartier-Bresson is also right in saying that often times as photographer, we try to “rescue” poorly composed photos by hoping that cropping it aggressively might save the image. But rarely this is the case. It is kind of like adding “HDR” or selective color (or even switching a color photo into black and white) to mask or hide the imperfections.

So if you want to improve your composition and framing: self-impose a rule of not cropping. I can guarantee you that this will improve your compositions.