I recently picked up a copy of “Photographers’ Sketchbooks“, an excellent book written by Stephen McLaren (co-author of “Street Photography Now”) and Bryan Formhals (founder of LPV magazine and the popular Tumblr: Photographs on the Brain).

Alongside “The Photobook: A History Volume III” by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger it is the best resource for photobook making, the philosophies of editing and sequencing, the importance of collaboration, explaining the working methods of certain photographers, their philosophies, and advice and thoughts on publishing via the printed medium (and on social media).

It is a beautifully put-together book, with tons of great “behind-the-scenes” materials, via photocopies of the photographers’ actual “sketchbooks”, contact sheets, and personal notes. I highly recommend everyone to pick up the actual book — and use it as a great reference when putting together your own book or body of work.

I personally learned a lot from the book, and I wanted to share some of the personal lessons I’ve learned from ingesting this beautiful tome of information:

Introduction

What is a “sketchbook”?

To start off, what exactly is a “sketchbook” — and how does it involve photography? Stephen McLaren shares a definition in the introduction:

“The term ‘sketchbooks’ refers not only to artists’ sketchbooks in the traditional sense— though some photographers, such as Mimi Mollica and the late Saul Leiter, do use paper sketchbooks extensively— but encompasses all the diverse preparatory work that goes into the finished ‘work’: Polaroid studies, maquette, exhibition proposals, smartphone pictures, diaristic projects, experimental image-making, small-circulation zines, online blogs and photo-sharing platforms. While many keynote pictures are here to be savored, other, quieter images, drawings, notebook entries and keepsake objects provide important visual context.”

Therefore a sketchbook doesn’t need to be just the traditional Moleskine (that all “artsy” photographers seem to carry). Rather, it can be any sort of document (physical or digital) that helps a photographer achieve his/her ultimate project.

A “sketchbook” can include maquettes (book dummies), exhibition proposals, smartphone photos, self-published zines, online blogs, and social media sharing platforms.

My experience with sketchbooks

Personally I’ve never been very sentimental with physical objects— in terms of writing down physical notes (in a Moleskine) or something of the sort.

I’m a digital native— I was wired into the internet since I’ve been 12 years old, and I prefer digital ways to record my thought. I have thousands of notes in my Evernote, I read most of my books via my Kindle app on my phone (although I do prefer a paper-bound book at the end of the day), I do all of my writing via the computer (never on paper), and publish all of my work online as well.

But at the same time— a part of me savors this analogue approach, of creating something physical.

For example, I prefer shooting film. I prefer the solace, zen-ness, and the “non-hurried” approach of shooting film. I savor physical photography books (although I do see a huge benefit of iPad photography books in terms of price and portability) and nothing beats a print (I prefer holding a print rather than just seeing it on a computer screen).

So when I first picked up “Photographers Sketchbooks” I was intrigued— I never considered myself keeping a “sketchbook” for my thoughts. But I realized that I have been doing it all along— only digitally.

So all of these lessons I will share later on in this article will focus on the methods of other photographers, as well as some of my comments and suggestions how you can apply it to your own workflow.

What successful photographers need to do

In the introduction, I found this section by Stephen McLaren quite valuable. He talks about the difficulty of pursuing photography today, and what a photographer needs to do in order to become “successful”.

Stephen McLaren is also an accomplished photographer (he makes great street photos), and also is a co-author of “Street Photography Now” — so the guy definitely knows what he is talking about.

McLaren shares the idea that having “outrageous talent” and “visual intelligence” is no longer enough— we need to know how to be editors (of our own work, and the work of others), we need to build and grow an audience (via social media and marketing), and figure out how to best publish our work. He explains more below:

“To pursue photography today as both an art form and a plausible career path can feel like an act of faith even for those blessed with outrageous talent and visual intelligence. It is no longer enough simply to master the interaction between eye, mind hand and a machine with shutter and lens; nowadays successful photographers have to know how to edit their work, seek out and develop an audience, pursue funding routes and understand the steps required to get things published or exhibited.”

He also mentions the importance of being forward-thinking with your work:

“The most forward-thinking photographers are also curators and documenters of their own work, constantly probing new possibilities for publishing and exhibiting.”

I often get a lot of questions from younger (or emerging) photographers— who vary in age, and want advice in terms of how to make a living or to be “successful” in photography (becoming well known, creating strong work, etc.).

I agree whole-heartedly with McLaren: nowadays a photographer can’t just be a photographer. A successful photographer needs to be a photographer, an editor, a publisher, his/her own marketing team, community-builder, and connector. A photographer needs to be a “jack of all trades”— and it will be the photographers who can juggle a lot of different roles and wear a lot of hats that will be the most successful.

For myself, I am certainly not the best photographer — nor the best street photographer. However I think what I do well is blog, educate, teach workshops, connect other street photographers, provide resources, provide examples of my on-going work (my doubts, flaws, and wins), as well as trying to be open and transparent. I have been able to build strong platforms to publish my work (and the work of others) via this blog, Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, Flickr, and other channels.

So realize that if you want to be a successful photographer— you want to be a generalist. I forgot who said it, but someone once said, “Specialization is for insects.” Don’t hyper-specialize in one field, because it will make you fragile and unable to adapt in today’s rapidly evolving and changing economy.

Lessons I’ve Learned From Photographers Sketchbooks

Moving on— I divided up some of the different sections and lessons I’ve learned from Photographers Sketchbooks:

1. Sketchbooks

So how do photographers exactly use their “sketchbooks”? Some of the photographers share their thoughts and approaches:

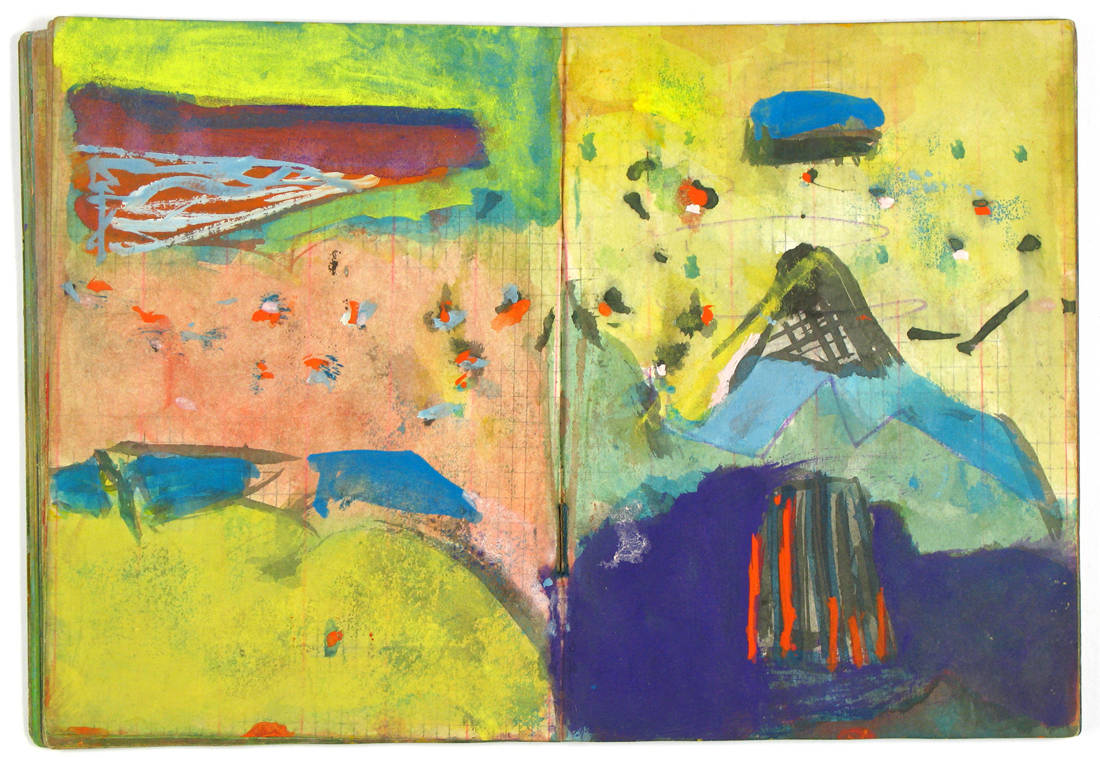

a) Express your thinking (Saul Leiter)

Saul Leiter is one of the most incredible photographers and human beings that have ever lived. He lived a simple and humble life— and truly photographed for himself. He was also a painter, and many of his “sketchbooks” were doodles for himself. Oh yeah, and he also shot street photography on the side.

Lester talks more about his feelings about sketchbooks below:

“I am very fond of my sketchbooks that I began in the 1950s and still work on today. I think there is a certain freedom when you are absorbed in painting a sketchbook. You are not burdened to do something important. You are not dealing in big things. You are just thinking and the sketchbooks are a way to express your thinking. They are very intimate. I work on my sketchbooks almost every day. If I had to choose what I value the most in my work I might choose my sketchbooks.”

To break down his thoughts, Leiter gets totally sucked into “the zone” or into a “flow state” when he is absorbed in painting a sketchbook. He doesn’t put unnecessary stress on himself— he uses his sketchbook to express his thinking, rather than making some great artwork.

Lester also makes his notebooks very intimate— and does it every day. Interestingly enough, he values his sketchbooks over all of his other works.

Takeaway point:

I think however you decide to work, consider your sketchbooks as something personal. Nobody needs to see your sketchbooks or your work-in-progress. Make it intimate, make it personal. Don’t take yourself too seriously— and get sucked into the process and the flow. Do it with love and care.

b) Collect “first drafts” of ideas (Mustafah Abdulaziz)

Photographer Mustafa Abdulaziz uses notebooks to collect scraps of things to remember and return to, and by storing these “first drafts of ideas”:

“My notebooks aren’t only for my projects or assignments. They’re everything I see in books, exhibitions, or while reading. I collect bits of things I want to remember and return to, and by simply storing them in any of my notebooks I can use them as first drafts of ideas in my head.”

Furthermore, Mustafa also uses sketchbooks/notebooks as a way to pre-visualize:

“My notebooks let me see what I imagined, as almost a pre-visualization. It’s in my head now. That’s what the process gave me: absolute certainty in the value of my dream.”

Takeaway point:

When you are working on a project, it is a process, it is a flow. You will encounter tons of great ideas along the way — and what better way to jot down the “first drafts of ideas” than put them into a notebook? These can be physical objects: paper airline tickets, advertisement flyers, random photos you find, or ideas that you just want to write down.

And you can also use your notebooks as a way to pre-visualize your final work— to keep you on-track to achieve your dream, whether it be publishing a book, putting on an exhibition, or preparing them to share on social media.

c) Journal to remember while shooting (Naoya Hatakeyama)

Photographer Naoya Hatakeyama shoots film— and often forgets details while shooting. Therefore writing down “data” back into a journal— Naoya can reference locations on certain days:

“While I’m shooting, there are many things that I have to remember, but I’m bound to forget them after a few days. So before the end of the day, I record that data in my journal. If I go abroad and shoot, when I come back to Japan and look at the journal, I can see that I was at a certain place on a particular day. That’s very convenient.”

Takeaway point:

If you are like me (a forgetful photographer/person) — using a journal or a notebook is a great way to jot down details or “data” of your shooting.

You can use this to record where you were when you took a certain day, what the light looked like, what time it was, the date, the location, and even your emotions you felt while you were shooting. This is all useful information you can cross-reference in the future (whether you shoot digital or film).

This is also particularly useful if you are learning how to shoot film— to record the aperture, film, and shutter speed you used (to get a sense of what the final product will look like).

Also by recording the location, time, and quality of light in your notebook— you can use that data to return to that location again, and perhaps re-shoot it (to make even stronger images).

d) To separate good/bad ideas (Kiana Hayeri)

Kiana Hayeri uses notebooks to keep track of “people, stories, and ideas” — and writes these all down to distill ideas and separate the good from the bad ideas:

“My notebooks help me to keep track of people, stories and ideas I come across. Often I meet someone or hear something that— not right away but sometimes later— clicks with an idea. Other times a story initially sounds brilliant and makes me all excited, but then when I write it down and revisit the idea later, I realize it is not as interesting as it first sounded.”

Takeaway point:

The benefit of writing down ideas and thoughts is that you can articulate them. Sometimes ideas end up clicking after you write them down. Other times, you write them down— and you realize that the idea was a bit silly.

But a great idea of writing down ideas is that you are able to put them down, let them marinate (rest), and you can re-visit the ideas later.

Having this time to let your thoughts soak and marinate gives you some distance from the idea— which will give you enough time to consider how good the idea really is.

This is also similar to the idea of letting your “photos marinate” — that sometimes you need to wait a few weeks, months, or even years to emotionally disconnect yourself from certain photographs— to judge them more objectively.

e) On using a notepad and pen (Mimi Mollica)

When Mimi Mollica has ideas, she writes them down physically via notebook and pen— and calls it an “extension of my brain”:

“A notepad and pen is an integral part of the creative process: it’s an extension of my brain. It’s great to have it with you when you are in the thick of work and you don’t have to have a straight line of thought, or experiences that flow logically. So my notepad is disorderly, full of hectic sketches and fragments of notes.”

And very much like a brain, thoughts can be disorderly, hectic, and not flow in a straight line. Thoughts are often fragments, bits and pieces— but all a part of the creative process.

Furthermore, Mimi also writes down notes in terms of what she shoots (subject matter), her personal feelings of how she feels the story is proceeding, and the names and details of people she meets— very much like an “old-fashioned” reporter:

“As it will be a while before my film is processed and I see the results, I make notes of what I have been shooting, record my thoughts about how the story is proceeding, and write down the names and details of the people I come across. These are old-fashioned reporting techniques, but visually they are also very important for sketching out the days ahead so I am ready for specific shots.”

Takeaway point:

Realize that the notebooks you keep don’t have to be super-clean or organized. Nobody has a truly clear mind. All of our thoughts are scattered and fragmented. They never come out totally crystallized in a stream. Considering that the human brain is just a bunch of different parts bolted together (and often fighting with one another) — this isn’t surprising.

However the more notes, ideas, thoughts, and feelings that you put into your sketchbook — down the line you can start finding patterns and linking ideas together— which will lead to other creative break-throughs.

Furthermore, you can also use the strategy of using a sketchbook like an “old-fashioned” reporter— to record important details to remember later on (especially if you are working on more documentary-style projects).

I often write down names and email addresses of subjects I photograph to promise to send them photographs later. I know other photographers who have written down addresses of their subjects— and have sent them prints down the line as well.

f) Keeping track of your learning (Laura Pannack)

Photography is a journey. It is a journey in which we are constantly learning.

One of the great parts of keeping a diary or a sketchbook is that we can see how far we have come in terms of our personal journey, and how much we have learned along the way.

Laura Pannack shares some of what she does— for example, taking random Polaroid snapshots along her journey— which is “another way of looking back at what I am learning”:

“Like picture-taking, my notes capture an expression, a thought, a feeling or a voice and acts as a simple aid to memory. I also keep a ‘Polaroid diary’ stored in a suitcase. This is another way of looking back at what I am learning. I’ve been learning how to use Polaroid for a few years now, but so far deem only one picture interesting out of the hundreds I’ve taken. It’s an ongoing, exciting, and incredibly frustrating education.”

Takeaway point:

I often see photographs as an extension of our memory— this is why we often take so many smartphone snapshots of our everyday lives (in order not to forget the good times, and to perhaps have a chance to look back).

I think this is also the great thing about having a Flickr stream— because they are sorted in a chronological order, you can go back to your really old photos (I dare you to look at the first photo you ever uploaded to Flickr) — to reminisce and be proud of your progress and education in your photography.

I think happiness in photography is two things: achievement and appreciation. It is about making better images, but also being grateful for everything you have learned along the way— and the progress you made along the way.

So you can also consider a photographer’s sketchbook or notebook to be a way you can document your life’s journey in photography— for your future self to reminisce and appreciate how far you have come, and the progress you have made.

2. Projects

Recently I have drifted away from the “single image” (aka— uploading single-images to Facebook, Instagram, Flickr to get a lot of favorites/likes) to working on projects/series.

The benefit of working on a project or a series is that you can better articulate what you have to say as a photographer. Photography is just another form of communication (a visual form of communication) — in which we are trying to express our thoughts, feelings, and statements about society, ourselves, or the rest of the world.

It is hard to make a story with a single image. Like a good book, you need a beginning, middle, and an end. Like a good film, you want a good sequence, variety of images, and flow.

If you publish your images in a book, you want to use the right paper, the right size of the book, choose the right cover image, have the right pairing and sequencing in the book (we will discuss more about book-making later in this article).

This entire section will be dedicated to working on projects:

Bryan Formhals on projects

Bryan Formhals is a photographer, publisher, and a curator. In the past he has been quite active in the Hardcore Street Photography Flickr group, is the founder of LPV magazine, and now curates and publishes the work of others extensively on the popular Tumblr “Photographs on the brain.” Bryan also works on many different projects himself on his website (most in the spirit of street photography).

He is also one of the best thinkers on social media and projects who can really articulate his thoughts.

There is a good chunk of the book when he talks about working on projects— and I have broken down his thoughts below:

a) What is a project?

To start off, Bryan shares his personal thoughts on the definition of a “project.”

Bryan realizes that there are a lot of different types of projects. But ultimately a project is “a series of photographs that are held together by a theme, concept or aesthetic association.” He expands below:

“Projects take many forms, and there is no single definition for what constitutes one. It could be argued that a photographer’s lifetime archive of images is a project; for the most part, however, a project is typically a series of photographs that are held together by a theme, concept or aesthetic association. Throughout the history of photography, this basic structure has been interpreted in countless ways and incorporates nearly every genre.”

As he mentions towards the end— the basic structure of a project can be interpreted in many different ways, and executed in many different ways as well.

Takeaway point:

When working on a project or a series— generally the images “should” have a theme, concept, or an aesthetic association. You want to have some sort of coherent idea you want to get across to the viewer.

Generally there are different types of projects I see:

- i) Typology: When you photograph a certain subject-matter repeatedly (cars, dogs, old people, people wearing suits)

- ii) Places: When you photograph a certain place (a city like New York City, your neighborhood, a whole country, or just parks or parking lots)

- iii) Concepts: When you photograph a concept, you are generally more interested in the idea (than the photographs). The photographs support the idea — rather than the idea supporting the photographs (the state of most “modern” photography)

- iiii) Diary: When you are photographing your own daily life, and making yourself (or close friends or family) as the protagonists. Great photographers who have done this include Daido Moriyamaand, Anders Petersen, Josef Koudelka, and Jacob Aue Sobol.

Also whenever you work on a project— I generally find the best projects are the ones that have consistency— in terms of the camera/lens/film used, the layout, or theme/concept.

But remember— there are no “rules” — merely suggestions and guidelines. So feel free to break any of them.

b) How to come up with a project idea

So let’s say you want to work on a project— but you have no idea what you want to work on.

How do you come up with a “good idea” for a project?

Bryan shares some thoughts:

“Photographers arrive at projects in a variety of different ways. For some, meticulous planning and research are required before starting; others discover projects only during the editing process.”

So if you consider yourself a “planner” — perhaps you want to meticulously plan and research before you start a project. If you are more of a “go with the flow” type of person— you can discover a project idea while you are shooting (or in the editing phase, and you see connections between the subject matter you photograph).

There is no one “right” way to start a project in this regard— just follow your personality type (you can even do a combination of both).

Bryan also mentions “best practices/guidelines” which can help photographers work on projects:

“There are, however, guidelines and best practices that have been passed down through the years that are beneficial to understand. Primarily the photographer needs to be passionate about the subject matter, and needs to have the discipline and patience to pursue the project over a long period of time. Once a project is underway, and a good amount of photographs have been accumulated, it is advisable to receive feedback from trusted sources, such as friends or teachers. A fresh set of eyes will help the photographer understand how others will view the project, and where it needs to be improved.

Therefore as Bryan shared, you want to have the following traits (regarding your project):

- Passion

- Discipline

- Patience

The reason is that good projects often take a very long time.

Furthermore, you also want to get honest feedback/constructive criticism from photographers/editors/friends you trust. This will help you get a more un-biased “outsiders perspective”— which will help you spot the holes and flaws in your project (which you are blind to).

Takeaway point:

Starting a project is often one of the most difficult things. I know a lot of photographers who stress out about finding an “interesting” project to work on. They bemoan the fact that they don’t live in an “interesting” place such as NYC, Tokyo, or Paris.

However some of the best projects I have seen have been in the most boring places. Take William Eggleston for example— whom only photographed his boring hometown. Blake Andrews has literally done a project on a town called “Boring”. Martin Parr’s best advice to young photographers is to photograph boring subject matter and make it interesting.

I recently came across a book called “Preston is my Paris”. To my understanding, Preston is a pretty boring place in the UK— but the photographer called it his “Paris”.

So realize that the best place to work on a project is often your own hometown. Why? You know it better than anyone else— and nobody has probably done a project there before.

Keep your projects local— try to photograph your own neighbors, family, friends, or people in the streets close to your house. You don’t need to fly somewhere exotic to work on an interesting project.

Also realize that a project you work on doesn’t have to be “street photography”. You can do a more personal documentary project on your own life— or the life of your family or friends.

I think at the end of the day— the best projects are the ones that are personal, have heart, soul, and a message you are trying to get across.

c) Editing process during a project

Bryan also shares some strategies while editing a project (when working with a friend or trusted colleague):

“For example, a friend may illuminate connections between themes and images that are unnoticed by the photographer, and recognizing which photographs resonate the most with others will help the photographer cut out weaker images and build around the stronger ones. This process will frequently be repeated many times over the course of the project, until it is ready to be presented to a wider audience.”

Takeaway point:

When I am working on a project, I seek out the opinion of my friends by putting my photos of my iPad (in the regular photos app) — and asking my friends to select what they think are the strongest shots (and ask them to ditch the weakest shots). I then ask them to articulate (as best as they can)— why they think certain shots are strong (and why the other shots are weak).

This helps me better understand the opinion and view of an outsider— and helps me also get rid of the weaker work.

I also ask my friends what patterns they see in my work— and what direction they think I should go, and what other types of shots I should build upon.

I also find the fact that generally the best shots float to the top (like oil on top of water)— and the weaker shots end up falling to the bottom.

While not everybody has 100% the same opinion— this is a good way to gauge the process of how your photography is coming. And with enough iterations of editing and building upon your project— you can make a solid and bulletproof body of work.

d) Publishing work-in-progress?

One thing that a lot of photographers do with social media is publish “work-in-progress”. Meaning, the project isn’t complete, but photographers are seeking the feedback of other photographers while it is on-going.

While there is a benefit to publishing work in progress, it can also be a detriment— as Bryan shares:

“These days many photographers will also share work-in-progress on the Web, although given the sheer volume of material appearing online each day, it can be difficult for any one project to attract enough attention to receive focused critical feedback.”

Takeaway point:

My personal opinion of sharing work-in-progress online? Don’t do it. Nobody will give you the focused and critical feedback on the internet. It isn’t that people don’t have good intentions— it is that the internet just isn’t very good for that. How many thumbs-ups or “likes” do you need to know your project is going in the right direction? A comment like “nice shot” won’t help you grow and develop your project.

I believe the only real way to get feedback on your photos is in-person. A second good contender is doing screen-share via Skype (or join.me) and getting uninterrupted 1-on–1 feedback.

When you are with someone physically, they aren’t distracted. They can point out (quite literally) the flaws of your images in terms of the framing, the composition. They can give you cropping suggestions. They can rearrange your photos quite quickly (I use the iPad for sequencing my images) or quickly create new edits of the on-going photos.

So in short, I don’t recommend publishing on-going work on the internet (if your intention is to get critical feedback). If you want to share you on-going work for the sake of it, then I think that is fine.

e) Have a working edit

Whenever I meet other photographers, I always ask them to share their work with me (via their smartphone, iPad, or laptop).

Most photographers are often caught with their pants down— they don’t have images ready to show, or a “working edit” of projects they are currently engaged in.

As Bryan Formhals illustrates— I think it is important to always have a “working edit” (rough draft) of what you are working on— to always be ready to solicit feedback from other photographers:

“Once enough photographs have been produced, it is important to develop a working edit that will illustrate the progress of the project and reveal where future work needs to be done.”

Takeaway point:

The best way to always have work ready to share and get feedback is just have it on your smartphone.

I don’t recommend using Dropbox or any other cloud-based service (sometimes the internet doesn’t load quickly enough in a cafe or a bar) — the best is to have it stored to the storage of your phone.

If you have an iPhone, just sync your photos from your computer to your phone via iTunes, and have different working edits of your on-going projects. If you have an Android, you can also drag-and-drop photos to your smartphone (I have a Mac and I use “Android file transfer” to do this).

Either that or always carry a tablet (iPad or other device) with you— and you can always harness the intelligence of other photographers to ask you feedback on editing, sequencing, or what direction to take your work.

f) Benefit of writing your project ideas

Bryan also gives a great piece of wisdom: write down your ideas — to clarify your thoughts and articulate them:

“Writing can also be a valuable aid in further developing a project. In writing about why one is interested in a project, or answering other questions about it, one can often uncover new ideas and themes that are worth pursuing.

Takeaway point:

I once read a technique called the “5 why” technique. The concept is to get to the root of any problem, issue, or core of something— you just ask yourself the question “why” 5 times.

For example, I am currently working on a “Suits” project— and this is how the “5 why technique” would play out:

- Why are you working on a “Suits” project? Because I used to work as a “Suit” (in the corporate world)

- Why did you work as a “Suit”? Because I wanted a job out of college, needed to pay rent, and wanted to make money.

- Why did you want to make money? Because I grew up never having money, and I felt that money would give me security, power, and make me happier in life.

- Why did you think that money would make you happier in life? Because I was dissatisfied with my life, in terms of seeing my friends have nicer physical possessions than me (smartphones, BMW’s, nice watches) — and I wanted to have spending power.

- Why did you want to have spending power? I guess I was quite dissatisfied with my life, and I though money and influence would bring me more happiness in my life.

So essentially my “Suits” project is about my own dissatisfaction with my own life— and thinking that working long hours and trying to earn more money would make me happier in life. Obviously that is false— but asking myself these “5 why” questions (and writing it down) helped clarify and crystallize your thoughts.

So consider asking yourself this “5 why” technique when working on a project, and write it down. This doesn’t just have to be photography either— it is a great way to find more direction and purpose in your life as well.

g) The need for experimentation

As photographers, are like scientists. We have certain outlooks and hypotheses about the world, and we want to test those assumptions and articulate our thoughts via our photography.

Like a good scientist, not every experiment will go well— but the more we experiment, the closer we will get to the “truth” of what we are trying to achieve with our projects.

As Bryan shares there is “no absolute formula for success” — and he suggests us all to have a “healthy dose of experimentation.”

A project is a personal journey— and we will all eventually reach our destination, through our own means:

“With any art form, however, there is no absolute formula for success, and a healthy dose of experimentation is always advised. Each photographer will arrive at their own process for developing projects, and evolve and refine it over the course of their life.”

Takeaway point:

I think one of the best benefits of working on a project is for self-exploration. We learn more about ourselves as photographers when we are working on projects for a sustained period of time. We discover what we are truly interested in, what engages us, what turns us on— and what we are passionate about.

And know that every project is different— and it will constantly change and evolve (as you continue to change, evolve, and grow as a photographer and human being).

There is no checklist or “10 steps to success” to make a good project (although my blog seems like that is what it advertises). I certain like sharing tips, advice, and my personal thoughts— but what works for me (or other photographers) won’t always work for yourself. You have to self-experiment, see what makes you happy, and see what works for you.

h) Pursue your own interests

There are often projects are series that we are commissioned to do (especially if you are a working, professional photographer). But most of the best and creative photographers I know are the ones that always work on personal projects.

By working on something personal— we can use our own experiences, and make a “broader story about society”. Not only that, but we can embed ourselves into the stories we are documenting— and make the projects more autobiographical. Bryan shares in this gem of a section:

“Personal projects— that is, work exploring a photographer’s own interests, rather than commissioned by a client— have become the defining projects for many ambitious photographers. […] The use of autobiographical elements in both these books [‘The Americans’ (1958) by Robert Frank and ‘Love on the Left Bank’ (1954) by Ed van der Elsken] demonstrated that photographers could mime their own lives for material, and expand on it in creative ways to tell a broader story about society. [Photographers Stacy Kranitz’s exploration of life in Appalachia and Kiana Hayeri’s stories about women in Iran] immerse themselves in the world of their subjects, and are not afraid to make themselves part of the story they are telling.”

Takeaway point:

There is no opinion or viewpoint that is more valuable than yours. You know your own thoughts, feelings, and emotions better than anyone else— why not expand on that and exploit it?

Know that as a street photographer, you don’t have a moral obligation to show reality as it is. There is no “objectivity” in street photography (or photography in general). You will always filter reality through your lens— in terms of how you frame, compose, and time your photographs. You decide the aperture, shutter speed, and ISO. You construct your own reality.

Make your projects personal. Try to make broader statements about society through your own life experiences. Embed yourself into your stories— and don’t be afraid to wear your heart on your sleeve.

i) Be flexible with projects

Projects often change and evolve as time goes on— embrace it. Be like bamboo, which is strong and firm— yet knows when to bend and yield when pressure is applied in different ways:

“Once a project has been started, it often evolves and expands in unplanned directions. As celebrated British fine art photographer Paul Graham cautions in his essay ‘The Unreasonable Apple’, ‘’I doubt Robert Frank knew what it all meant when he started, or for that matter Cindy Sherman or Robert Mapplethorpe or Atget…so you shouldn’t expect it. The more preplanned it is, the less room for surprise, for the world to talk back, for the idea to find itself, allowing ambivalence and ambiguity to seep in, and sometimes those are more important than certainty and clarity. The work often says more than the artist intended.’’”

Takeaway point:

We never know what lies in the future. The only thing we are certain of is the present moment.

Think about how you can currently work on your project in the present moment— right now.

What kind of photos do you need to take? Where can you go today to shoot? Do you already have some material that you can edit and sequence today? Is there a photographer you can meet today to get feedback and constructive criticism on your work?

Also don’t get too married to your initial idea. Be open to the opinion of others— and change your project if need be. Don’t fall victim to the “sunk cost” fallacy. If you have 100 photos in your project, realize that you have to often “kill your babies”— and edit it down.

Robert Frank photographed over 750 rolls of film for his “Americans” project (~28,000 shots in total) and only had 83 published. That is a pretty low keeper rate— and he had to edit out tons of images.

So let the project evolve, change, and move direction as time goes on— don’t become too rigid in your views— or you will become fragile, brittle, and break.

j) How to overcome “photographer’s block”

I think photographers are like writers— we often hit “photographers block” (kind of like writer’s block) — in which we no longer feel inspiration for the project, or we feel we have hit a dead wall, and we have no direction which way to go.

So what can we do when we hit a wall, or an “impasse” with a project?

Bryan shares some of his thoughts:

“If you find yourself at an impasse with a project, it’s best to discuss the work with trusted friends to see what they think. Another option would be to go to portfolio reviews to see what experts within the industry think of the project. This feedback will be incredibly valuable and should give you a good idea about the state of the project.”

Takeaway point:

I think it is good to hit roadblocks in your project— because they are valuable times in which force you to reassess your project: whether it is really worth doing, if you are truly passionate about it, or the direction it is going in.

Sometimes if you hit a roadblock in your project— the best is just to ditch it or kill it. Don’t become married to your projects— if it isn’t working out, best is to discard it and move on.

But perhaps there is something in your soul that tells you that you must keep going on in your project— follow your gut. I think curiosity and passion is the best ways to know whether a project is worthwhile to continue pursuing.

Bryan recommends getting feedback from others — which is also a great tool. You can get encouragement from others (telling you to continue the project)— or honest feedback that it might be best to end the project.

Ultimately the decision lies with you— whether you decide to continue the project or ditch it. But always seek the opinion of others before making your own personal decision.

k) Taking a step back

Sometimes getting some distance from a project is important to know whether it is truly worth pursuing. Time is often the best test of good ideas:

“Each project will have its own natural progression and there will likely be times when it is beneficial to step away, because time can change one’s perspective. Thomas Vanden Driessche, for instance, stored his diaries from India for a few years before revisiting them and giving them new life. Jim Goldberg continuously mines his archives looking for new angles on his photographs, which he can then explore through new projects or in new edits of existing work. British social documentary photographer Paul Trevor has mined his archive to develop new books, for example ‘In Your Face’, a project ‘exploring the malignant impact of free-market economics in the late 1980s and early 1990s’”.

Takeaway point:

One of the tips I have heard for writers is that if you ever write a book, lock your first draft in a drawer for a year, then a year later— open the drawer, re-read the book, and then edit it. This will help make the book a lot better— because you will have emotionally disconnected from the book, you can see it with a more critical eye, and be much more discerning when editing.

I have found the same goes with my photography projects. It takes me about a year or so whether I know if a project is really worth showing or not. Not only that, but a year also helps me become more emotionally disconnected from my bad photos, and helps me be more objective in the editing phase.

I also often re-visit my old projects, and edit out certain shots (or re-add certain images). Furthermore, I also edit out certain projects in general (which I no longer think are good).

For example when I re-designed my website portfolio, I removed all of my projects from my site, and only re-uploaded the ones that I felt were really strong and also had personal significance for me. Even though I have worked on about 10 projects the last few years, there were only 3 projects that were meaningful to me: my “Suits” project, my “Grandfather” project, and my on-going “Only in America” series.

So don’t feel like you need to be in a rush to work on your projects. Take your time, and let time be the ultimate test of your work.

l) On abandoning projects

As we talked about earlier— sometimes it is good to abandon your projects. Don’t feel bad, it might end up being a good gateway into a future project. Bryan expands:

“The hard reality, however, is that many projects will fade into obscurity, unfinished, or will be absorbed into new edits and projects. If you speak with enough photographers, you’ll hear about many such abandoned projects, sometimes tucked away in a physical archive, never to be seen again, or languishing on websites, buried among other material. They still have value, however, in the evolution of a photographer’s work. Abandoned projects can serve as bridges to new projects; they allow the photographer to hone their ideas.”

Takeaway point:

I love the idea that an abandoned project can serve as a bridge to a new project.

For example, I worked on a photography series of Detroit— which I felt was ultimately not strong enough as a body of work (too few images)— but I ended up realizing from a good friend of mine (Sean Lotman) that I could use photos from my Detroit series into my new “Only in America” series (which will be a much broader project about America in general).

So never see your abandoned projects as failures. See them as growing experiences that have been part of your journey as a photographer.

Similarly, I think that you are only as good as your weakest images. Therefore, I often go back to my old Flickr archives, and routinely delete (or mark private) photos that I used to think were good (and now think are weak). It is a good memory of what I used to think was a good image— but at the same time, marks my progress and growth as a photographer.

m) Always be questioning yourself

Life is an on-going journey— we will never make one project that will totally satisfy us. We need to constantly be asking ourselves questions about our lives, our interests in photography— and issues we want to explore. Bryan shares some concluding thoughts on working on projects:

“The projects in this book encompasses many different genres, formats and motivations, but the one thing that connects all the profiled photographers is that they pursued projects on subjects that interested them. So: what are you interested in? At what or whom do you point the camera? What do you like to read about? What issues do you think about often? The answers can normally be found in your life, so look around, and get started.”

Takeaway point:

Pursue projects that interest you (not others). Ask yourself questions regarding your motivations. What interests you? What subject matter fascinates you? Do you prefer black and white or color? Why do you photograph? What excites you the most in photography? What subject matter scares you the most in photography? What genre of photography is the most challenging and rewarding for you?

As Bryan said— the answers often lie in your own life, “so look around, and get started.”

3. Social Media

One section I found quite illuminating in “Photographers Sketchbooks” is on publishing and social media. I was able to gather thoughts from different photographers who approach social media in different ways— and compiled some thoughts below:

a) Social media giving “freedom of workflow”

On a section in publishing, Bryan Formhals shares the importance of social media (instead of just traditional publishing). While a lot of photographers aim to make a book— others (especially the “digital natives”) will prefer social media as a way to sharing their photos with the world:

“‘The photographic reality of this moment is ‘freedom of workflow’, says critic and collector Loring Knoblauch. For many photographers, a physical photo book is the ultimate goal, but this is far from the only option. Some photographers will work towards creating prints and installations for a gallery exhibition, while others will use digital platforms such as Instagram or Tumblr to present their photographs to the world.”

Takeaway point:

I do think ultimately the best way to present your work is in a photography book, because it gives you the chance to create a physical manifestation of your images. A book is an object you can hold, interact with, and keep for a long time. Who knows how long your Facebook, Flickr, or Tumblr account will exist?

But at the same time— social media gives us the power to reach an unlimited audience. In theory, millions of people can see your photographs on social media— whereas only a couple dozen or hundred will see your photographs in a book-form.

There are many different ways to publish your photos on social media.

Personally, I have found Tumblr to be the best way to share mini-sets and series, because it allows you to create diptychs and triptychs, and mini-sets (and re-arrange the sizes of the images).

Facebook is great for sets and singles images as well— but then again you have to deal with the distraction of getting messages, and pop-up notifications.

Flickr is good for single images, not so good for sets or series. And the good thing about Flickr is that it is the biggest home for street photographers (especially if you consider the Hardcore Street Photography Group).

Instagram is good for photo-sharing as well, because everyone is on mobile (personally I prefer to be on my smartphone or iPad over my laptop). But the downside of Instagram is that it has emphasis on the single image, not so much on projects.

However on Instagram there are ways you can work on projects— by hash tagging a title of a series, or just uploading single-images (part of the same project) in a row.

I also find Instagram as a good way to show your audience the “behind the scenes” of what you’re working on. For example, I use my Instagram more of a glimpse of my everyday life (what I am reading for photography books, or my blogging updates) — or just photos I shoot on my smartphone. I personally don’t like using “Squaready” or other apps that make your 3×2 ratio photos into squares. I think Instagram was built for squares— and therefore should be presented as squares.

Of course this is just my opinion— I have a lot of friends who use their Instagram as a portable portfolios — which works well for them.

Ultimately you want to consider your social media platforms for a certain purpose. What do you ultimately want out of social media? Do you just want to get loads of comments, favorites, or likes? Do you want to show people behind-the-scenes footage that will interest them? Do the photos you share add value to the lives of your viewers, or are they just self-gratuitous?

There is ultimately no “right” way to do social media— but my suggestion is be conscious of how you are using social media, and do it purposefully and with meaning.

b) Social media for engagement

The difference between a tactile book and social media is that a book is often a lot engaging than social media.

With a tactile book, you can interact with it (feeling the paper, flipping through pages, holding it) — but you can’t leave comments, contact the photographer, or give direct feedback. With social media you can.

Bryan shares some differences between a book and social media— in terms of engagement:

“The tactile experience of a book, along with its design elements, allows the viewer to become almost physically present in the photographer’s world, holding it right in the palm of their hands. Presenting photographs on a blog or a photo stream gives the audience an opportunity for a more fluid and sustained engagement with the material, following the story as it grows and evolves over time.”

Takeaway point:

One of the strengths of publishing photos on social media is the fact that you can better engage with your audience. I think making photos that are engaging is a better way to interact with your viewer, to make them a part of the journey and process (rather than passive observers).

c) Having a balanced social media strategy

What are some other advice for photographers regarding social media? What is the right formula, or the “secret sauce”? There isn’t any— Bryan suggests to have a “balanced approach” in terms of social media:

“The best way forward is to take a balanced approach in developing a social media strategy, which will vary from photographer to photographer, depending o their individual objectives. Photographers will need to determine which platforms they are going to utilize and how frequently they will be publishing and communicating with their followers.”

Bryan also shares the thought that each social media platform is better for different tasks and goals:

“Platforms such as Twitter and Instagram tend to require daily attention to get their full benefits, while Facebook, blogging and Tumblr can be updated more intermittently and are generally saved for sharing news, achievements, and new projects.”

Lastly, Bryan also encourages social media to be engaging and a two-way street, rather than an avenue to just publish your work and show the world how awesome you and your photos are:

“An important element to keep in mind is that social media is a two-way street, meaning that it needs to be used to connect and communicate with other photographers, rather than simply for publishing one’s own content.”

Takeaway point:

There is a reason why they call “social media” social. Traditional publishing was always a one-way street, where the publisher would just put the content in front of the viewer, and have the viewer passively consume the information (like television or newspapers).

However with social media, it has become a two-way street, with users able to interact directly with the creator— offering suggestions and feedback. This is what has happened in the “Web 2.0” world.

Based on my personal experiences, this is how I have used diverse social media platforms:

- Facebook: To publish links to my blog articles, to ask questions, and to share projects/images.

- Twitter: To publish links to my blog articles, engage people on a 1:1 basis (kind of like public text-messaging). Also to follow other influential photographers.

- Tumblr: To upload mini-series (sets of 3–5 images), or single images. Or to cross-post with photos from Instagram (so I can later copy/paste my Instagram photos to blog posts, etc.).

- Google+: To share articles I published. Not many photographers use Google+ anymore (when compared to other social media platforms).

- Flickr: To publish strong single-images (to show people I am still alive). Check out the Hardcore Street Photography Pool or Forum (for interesting pages or discussions).

Of course this is just how I use social media— develop your own “balanced” social media strategy— what works for you.

d) Connecting with like-minded individuals

For me, one of the best things about social media is that it has allowed me to meet interesting, diverse, and passionate street photographers from all around the world— which has lead me to meeting them in-person. This has given me the chance to engage with them in terms of sharing ideas, editing work and sequencing it, and just inspiring one another.

While publishing photos and being seen by a lot of other photographers can be useful in social media— I think the biggest benefit of social media is connecting with like-minded individuals.

Bryan encourages everyone to join the conversation:

“For most ambitious photographers, having their work published so it can reach an audience— whatever the format, is the ultimate goal. While the variety of options for publishing can be dizzying, they also offer contemporary photographers many exciting way stop reach and engage with an audience. In the vibrant communities that have developed through social media, it has become easier to connect with like-minded individuals willing to share information about best practices and opportunities. They are out there and they are waiting for you to join the conversation. So jump in, publish that zine or book, and see what happens!”

Takeaway point:

Social media isn’t the holy grail— nor the golden bullet to get your work best published, recognized, or seen. Social media is at the end of the day— simply another tool to connect with other individuals (while also having your work seen).

I have personally utilized social media to help me be more social— and to reach out to those who are much more knowledgeable to me (who have helped me a ton). Furthermore, I also see social media as a way for me to share some of my thoughts, experiences, and images with others (via this blog and other channels).

Ultimately think about the value you are adding to others via social media. Rather than expecting social media to help you, ask yourself, “How can I help others?”

e) On using Instagram

Photographer Peter DiCampo shares his strategy in terms of using Instagram— that not every photo had to be a “masterpiece” — but Instagram was a good sketchbook for “communicating an impression”:

“Professionals also revealed in showcasing the more personal material taken on assignment that ordinarily might not have made the cut. Not every upload had to be a masterpiece; it was more about communicating an impression.”

Takeaway point:

The thing I love most about Instagram is how personal it feels. My favorite Instagram feeds aren’t just mobile portfolios of photographers. They are an inside glimpse of their thinking process, their everyday life, and impressions of the world.

I also think that because people have lower expectations on Instagram (not every photo has to be perfect) — it allows for a lot more experimentation.

For example, I shoot a lot of urban landscapes on my phone, process them in-camera with VSCO, and upload them. I wasn’t quite sure how people would react to my urban landscapes (photographers know me most for my photos of people)— but I was quite pleased with the feedback that I got.

Also the nice thing about shooting urban landscapes and sharing them is that I have memories of the places that I have visited along the way— and some of the beautiful things I have seen and experienced.

So long story short, make your Instagram personal.

f) Blog as a sketchbook

The photographer Muir Vidler who runs the blog “More Muir” uses his blog as a sketchbook— to share ideas, to collect images, writing, and telling stories:

“I don’t think it is too much of a stretch to say that I use my blog kind of like a sketchbook, or scrapbook, in that it involves collecting photos, writing a little bit about them, telling a story, and saving and using material that might otherwise languish in a drawer or a hard drive.”

The blog has also helped him reflect more about his current (and future projects):

“It also is helping me think about the new project I’m working on now, and how I will approach it— what I want to ‘say’ with it and what kind of photographer I am in general. It makes me understand what I’m good at, what I’m shit at, what I like, what I don’t like, how I want to be shooting and presenting my work in the future. I’m also enjoying the writing side of it and want to experiment a bit more with that.”

Takeaway point:

I have learned so much through working on this blog. Over the last 4+ years, I have wrote over 1,000+ blog posts— which is a trail of my thinking, growth, and development as a photographer (and human being).

I love being able to go back to older blog posts, to see how I used to think about 2–3 years ago, and how some of my thoughts have changed (while some have stayed the same).

I encourage every single photographer out there to start a blog— there is no better way to share your personal experiences, thoughts, and images. A blog is something you own (especially if you self-host it via wordpress.org via your own server).

Make your blog a digital treasure chest— a scrapbook that you will look back on, revel, and enjoy.

4. Book making

This section of the article (which is getting pretty damn long, thank you for sticking through) — is going to be focused on book-making (something that interests me a lot):

Jason Eskenazi: The Making of “Wonderland”

One of my favorite street photography books (published in black and white) has to be Jason Eskenazi’s “Wonderland” which was recommended to me by my good friend Charlie Kirk.

Jason shares his thoughts in terms of making a book:

a) On creating “Wonderland” as a fairytale

Oftentimes people make photography books as a “best-of” collection: that they stick all their best single-images into a book, and expect it to somehow have some sort of story or narrative.

I feel the best photo books are the ones that tell stories— that have narratives.

Jason did a great job in organizing the photos he shot in the former USSR (for over 10+ years) into a fairytale format. He shares more:

“Back in the mid–1990’s, walking through a park in Moscow with a friend, discussing how I might organize my Russian photographs in book form, I brought up the idea that Russians love fairy tales. As a photojournalist I was weary of how easily the ‘truth’ in photos could be manipulated depending on the caption or context. I wanted to use my photos for their imagery, depth, and meaning whereas the journalistic value was mostly in the facts or statistics they were supporting. So I began to decontextualize the images, captions, in the form of a fairy-tale book.”

The great concept of the fairytale for this project is the fact that because he was documenting Russians— he tried to find a “Russian-like” way to present the images.

Also based on Jason’s experiences as a photojournalist, he knew how easily the “truth” could be manipulated in photographs— and wanted to decontextualize the stories as a fairytale book.

Takeaway point:

When you’re putting together a book — think about the story or narrative you are trying to say. The sequence matters, and realize that you can create your own version of reality through your book— don’t try to aim to simply tell the “objective truth”.

b) On creating a narrative

Jason tells us more about his love of cinema and literature, and how he was able to use techniques he’s learned in his photobook and project:

“Since I’m a cinema fan and studied 19th-century literature, there needed to be a dramatic narrative arc in the sequence of images, as in films and novels, and not like the many photo books that focus on a particular photographer’s greatest hits or a single journalistic event. I spent days upon ‘daze’ in a copy shop in New York assembling a mock Soviet-style fairy tale from my photos and writing a story around them. It was called ‘Motherland’.”

Takeaway point:

In terms of making books and narratives, study film and literature (and any outside fields). The best projects, photography, and books often come from outside of photography.

c) Changing the narrative

Jason also shares how “Wonderland” went through several iterations— and how it changed and evolved over time:

“The book treatment went through other machinations. At one point the idea of being a guest in Russia became important, so I structured the narrative like a hotel stay and used an enlarged hotel guest card as a model for the cover. Although that theme was short-lived, in the final versions I kept the purple of the guest card on the cover, and the idea of being a guest in Russia in the postscript.”

Takeaway point:

Realize the script of the book can change— so be open and flexible.

d) Following the fairy-tale structure

When trying to put together this fairy-tale structure for “Wonderland”, Jason did some academic research of fairy-tale structures to give him greater insight:

“The title eventually changed to ‘Wonderland: A Fairy Tale of the Soviet Monolith, as an ironic twist on what the Soviet Union had promised, and what has disintegrated while I was there. Over the years I had collected some old books of fairy tales in Moscow clear markets. I began to read academic writing about fairy-tale structure and noticed that I already had been following this with my photos. A parental figure dies and a child sets out on his or her through the dangers, usually sexual, of the world to maturity. I saw the Soviet Union as the parental figure, dead, along with the felled statues of Communist hero, and the Soviet children left on their own in the new world of democracy and capitalism.”

Takeaway point:

When you are onto a good idea, do some research— and see how it can inform and help build your photography project/book.

e) Editing and sequencing

An interesting way Jason ended up editing and sequencing “Wonderland” was by having small Xeroxed images (nothing fancy) and carried them around with him— showing them to friends, and asking for sequencing suggestions. This helped him create the structure of the book:

“I had a red rubber-banded stack of small, dog-eared Xeroxed images that I carried around with me, and I would show it to friends and try to sequence them. The original seven chapters turned into three, structured by the idea of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis; white, black and grey.”

Takeaway point:

The benefit of having images always with you is that you can always get feedback in terms of the images themselves— and sequencing suggestions. It is much easier to sequence images (when physical small prints) than on an iPad (although an iPad can be more convenient).

I know a lot of photographers who carry around small 4×6 prints (nothing fancy) — that are good mobile portfolios, and helpful in sequencing and editing projects.

To sequence with 4×6 images, you can just put them on a floor, and see what kind of connections and pairs end up happening. You can also make a good sequence.

Furthermore, editing is easier with prints: you can make two piles: one pile for “keep” and another pile for “ditch”.

Digital is great for presenting and sharing work— but nothing beats having a physical stack of images or prints to share.

f) Making a book dummy

A lot of photographers often create “maquettes” (book dummies) to experiment with in terms of layout, sequencing, and pairing of images (before publishing the official book).

Jason came across a great idea in the 90’s— to make a book dummy with a small photo printer.

The interesting thing about this is that the dummy book of small prints ended up becoming the structure for the final book:

“In New York, in the late 1990s, a friend showed me another method of making a book dummy, using a photo printer. The size was determined by the printer, and I had a small one. Since the pages were folded in half to make the book dummy, it could be no more than 5’’ x 8’’. I dropped the text of the fairy tale, but retained the story in the structure and sequence of the images. This version had over a hundred images in it. It was shaped like a brick due to the stacking method of making the dummy.”

Takeaway point:

Making a book dummy doesn’t have to be fancy. You can just use a Xerox machine, your own photo printer, and you can keep it small.

g) On approaching publishers

As amazing as “Wonderland” was in terms of the story, sequencing, editing, and images— Jason had a tough time getting them published as he illustrates below:

“In 2002 I went to the Frankfurt Book Fair with this brick of a book. I sought out publishers whose books I liked. But I heard the same story over and over: they liked the material but they wouldn’t be able to make money with it.”

Takeaway point:

Getting your photographs published by a publisher is no easy deal. You can have incredible images— but if they don’t think the images will sell, you’re going to have a tough time.

So I guess the lesson is this: getting your photos published isn’t always a reflection of how good you are as a photographer. Often there are external factors (money is always a big one) that gets in the way.

This is why self-publishing and print-on-demand is so liberating to many photographers now, because there are no longer any gatekeepers. We will talk more self-publishing and print-on-demand in a later section.

h) Making a portable book

A lot of photographers are enamored with making a huge hardcover book (like Steidl). But often the best photobooks are small, compact, and easy to carry around.

Jason made the conscious effort to make “Wonderland” small and portable— kind of like a novel you can easily carry in your bag:

“I now wanted a book that someone could take on the train and look at. A novel size. I liked some of the more industrially styled cardboard books I saw in bookstores and I knew that I did not want a typical photo on the cover.”

Jason also tells the story of how he finally found a publisher:

“Finally, in the mid–2000’s I found a publisher in New York, and received a donation from a non-profit organization to support the printing costs. Some sequence issues and editing had to be ironed out.”

He continued to show images to friends, asking for critiques and feedbacks— and even polled them on what the best images were (like a survey):

“I continued to show small Xeroxed copies of the images to my friends, asking them to initial the flip sides of the pictures they liked. It was like a survey.”

But the best technique? Just putting the images on a metal board (and looking at them everyday):

“Nothing was better than the metal board for keeping your photos up and in front of you while you went about your business day after day.”

Jason also discusses some difficulties they had with making the cover of “Wonderland” (and other issues)

“The general rule is that publishers own the cover, and I was unhappy with the fancy, flowery not, which reminded me of English fairy tales and Blake— I still wanted an image on the cover— but the publisher said he would not do the book without it. Over the next year there were so many unexplained delays in printing the book that I took the publisher to arbitration and in the end fewer copies were printed than originally promised. It was finally published in 2007–8 and won the Best Photography Book award at POYi (Pictures of the Year International).”

Takeaway point:

If you are going to work with a publisher, it won’t always be an easy and happy journey. You have to collaborate with others, and often fight for your own opinion and vision.

Furthermore when you are publishing a book, consider the size of the book— how do you want people to interact with it? I personally prefer smaller books, as they are cheaper, simpler, easier to carry, and much more pleasant to look at.

i) Getting publicity

Jason also shares how he was able to gain more publicity for “Wonderland” while working as a museum security guard:

“In 2008, while working as a museum security guard, I managed to get ‘Wonderland’ sold in the museum bookstore. The media picked up on the story and the remaining 712 copies of the book sold out briskly.”

Furthermore, he was even able to utilize blogs and social media to get in contact with an old friend (who offered to reprint “Wonderland”):

“An old friend read a blog article about me and called to say he would loan me the money to reprint. So I created Red Hook Editions, named for the Brooklyn neighborhood I was living in, and paid him back within two months from the sales from the reprint.”

Jason also shares his motives for his next book:

“I will not print the book again but instead plan to use the profits to publish the next one, which will incorporate some material that didn’t make it into ‘Wonderland’ (now to be part of a trilogy), returning to some of the original characters and situations. But what to do with the verticals…?”

Takeaway point:

The difficult thing about self-publishing is getting publicity for your book, and actually selling them. Otherwise you will have hundreds of copies just languishing in your closet or basement.

A good way to get your photography book out there is by doing interviews with photography blogs, by doing guest articles for blogs, and getting connected to other publishers, editors, and photographers in the industry.

Know no matter how good your book, project, series, or concept is— you will still need to market it effectively.

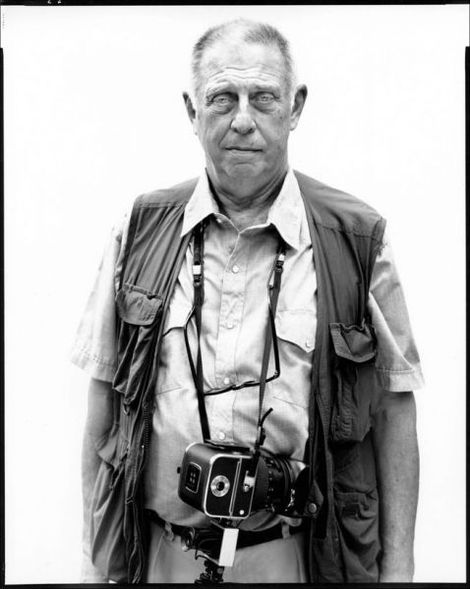

Peter van Agtmael on making “Disco Night Sept 11”

Another great photographer, Peter van Agtmael from Magnum shares his in-depth story of how he put together “Disco Night Sept 11”— his first book:

a) On editing process

When it comes to working on a project or editing a book, the most intimidating thing is to edit a huge amount of images (often shot over several years). Peter shares some of his difficulties in the beginning— and how getting help from trusted colleagues has helped him:

“‘Disco Night Sept 11’ is my first real book and I started the work when I was 24, so I was learning about photography and book-making throughout the process. The editing really started with Christian Hansen at the end of 2007. I’d met him a few months before, outside a bar, after getting back from Afghanistan. […] When we ran across each other a few months later at my friend Alan Chin’s party, I told him I had no idea how to edit nearly two years’ worth of work. He came over to my grandparents’ place where I was living at the time and ended up staying for three days. By the end of it, I had a new understanding of the work, and more confidence in it.”

Peter was also fortunate to get lots of honest and critical feedback from his fellow members in Magnum— as he said that “almost everyone is happy to give their opinion”:

“A few months later, I joined Magnum and began getting some great advice from the photographers there. Almost everyone is happy to give their opinion, and even Josef Koudelka would come to most meetings with a stack of prints. I was very honored when one day he asked me to edit them, until I realized he was asking every single person in the room!”

Takeaway point:

People and photographers love to share their opinion and feedback. When you are stuck in terms of finding direction or editing a project, always seek the feedback of trusted colleagues, friends, and people you trust.

b) The best shots often raise to the top

Peter also shares the benefit of getting feedback from other photographers: the best shots often float to the top

“I’ve noticed that no matter who edits the work, there’s almost always a core group of images that float to the top. That’s usually a good starting point.”

However at the same time, sometimes you will find opposition to the shots that you love (that nobody else thinks is good). In this case— you must know how to defend your position, or know when to give them up:

“Of course, there are always photographers I admire who hate certain pictures I love. The idea is to be able to defend one’s position coherently in the face of opposition.”

Takeaway point:

The benefit of getting lots of feedback from others is that the best shots often float to the top, but then again— people also generally agree which the worst shots are.

Use the feedback of others as a barometer for your images— but know when to defend your own opinion.

c) On taking your time

When it comes to photography (especially with social media and the internet), we feel so rushed. We feel that we need to get out work out there quickly, and efficiently.

But the greatest projects often take a long time. Koudelka’s “Gypsies” took him over 10 years and Robert Frank was only able to achieve his vision for “The Americans” after shooting 500+ rolls of film.

Peter encourages us to take our time:

“I’ve been in no rush to finish the book. It took almost three years from beginning to end. When I hit a wall I didn’t try to force anything; I just went about my other work and eventually the right answer would occur to me. Of course all this is very subjective. The book could have been very different from the way it turned out.”

Takeaway point:

I think when working on a book or a project, my favorite ones I have seen often range from 3–10 years. It takes a lot of time to shoot the images, edit and sequence them, design them, and get feedback.

Also when you hit roadblocks, don’t try to force it. Simply take a Zen or Taoist approach and let it go for a while, then return to it.

I think as photographers, as long as we can publish one meaningful and powerful book at the end of our lives— we have done our job as photographers. Don’t feel the need to publish dozens of mediocre books, aim for less. Less is more.

d) What he wanted out of the book

It is also important to know your own personal motives for a book. Peter shares his personal goals:

“I wanted to make it a work of journalism, a diary, a document for history as well as a book of photography. These can be opposing forces. They required compromise. If I had just been making a book of photography, it would have probably have had half the number of pictures and far more limited captions. Maybe one day I’ll make that book.”

Takeaway point:

When you are putting together a book, know exactly what you want your final product to be— and strive towards it. Know that sometimes compromise is required as well.

e) On narratives

Peter also shares the narratives behind the book he made— the focus being emotional, not narrative:

“The book contains several narratives. The main sequence grows darker and ever more violent, and constantly jumps back and forth between the war and home, sometimes in indistinguishable ways. It’s an emotional narrative, not a storytelling one.”

Peter also shares how the book was designed to involve the viewer:

“The nineteen gatefolds are more linear. They elaborate in photos and words on people or situations that would bog down the book if they were included in the main sequence. This basically allows the book to be seen in a number of ways. With or without foldouts. With or without captions. You get as involved as you want to go.”

Takeaway point:

In a recent lecture on book-making I attended at the LCC in London (by Bruno Ceschel) — he shared how the best books are interactive, that involve the viewer.

Peter shares how his book can be seen in a number of ways— and it is up to the viewer how he/she interacts with the book.

Furthermore, Peter also made the conscious decision to make the photos about an emotional (not storytelling) narrative. Often books tend to be too linear in terms of timeline or stories— but “there is more than one way to skin a cat”.

Think about what kind of edit, sequence, and flow you find suitable for your book and project— and go for it.

f) Being careful with words

Another great insight I learned from Peter (through the criticism he got) was that a photographer needs to be careful with words when putting together a book:

“One early memory was when Uimonen came into the Magnum office and I asked him to look at the book. He opened it, read two sentences, closed it, walked out of the room and said, ‘Be very careful with words.’”

Takeaway point:

A photography book is generally focused on images— but the words often have as much power in a book as the images.

So when putting together a photography book— make sure to get a damn good editor to help you distill the ideas you want to convey in your book.

Furthermore, a good designer also helps tons too (with knowledge of typography and type).

g) On collaborating with others

Peter also shares the process of collaborating with designers on making the book:

“Working with Yo Cuomo and Bonnie Briant on the design was an eye-opener. A relatively simple-seeming process had endless moving parts. They patiently guided me through it with humor and wisdom.”

The good thing about trusting a designer is that they know more about the moving parts of making a book (paper, the glue, the binding, the spine, the feel, the size, etc.).

Furthermore, Peter encourages seeking the advice of others (you trust) and deconstructing their work:

“If I can recommend anything, it would be to seek out the advice of people you trust. I’ve thoroughly deconstructed the dummies of other photographers and royally annoyed them in the process, but it only proved their vulnerability. Oftentimes they’d simply slapped something together without much intentionality. That’s pretty easy to recognize. So be prepared to defend your choices. If you can’t, you probably don’t have much of a book.”

Takeaway point:

Know that making a book is ultimately a collaborative one. You can’t do everything yourself. You need a knowledgeable designer, you need a knowledgeable editor, and other photographers to help you in the process (an exception being William Klein).

But also know that every single photographer out there (even Magnum photographers) have doubts, fears, and self-criticisms of their work. They are vulnerable as much as us.