All photographs copyrighted by Todd Hido.

This is part 2 of my write-up on Todd Hido’s new book: “Todd Hido on Landscapes, Interiors, and The Nude: The Photography Workshop Series“. You can read part 1: “Lessons Todd Hido Has Taught Me About Street Photography (Part 1).”

You can also download the entire article free via .docx, PDF, and Google Doc.

11. Photography is about position

One lesson I learned from David Hurn (Magnum photographer) is that in photography there are two main variables you control: where you stand and when you click the shutter.

This lesson is also mirrored by Todd Hido who shares the importance of position (where you stand) when you make images:

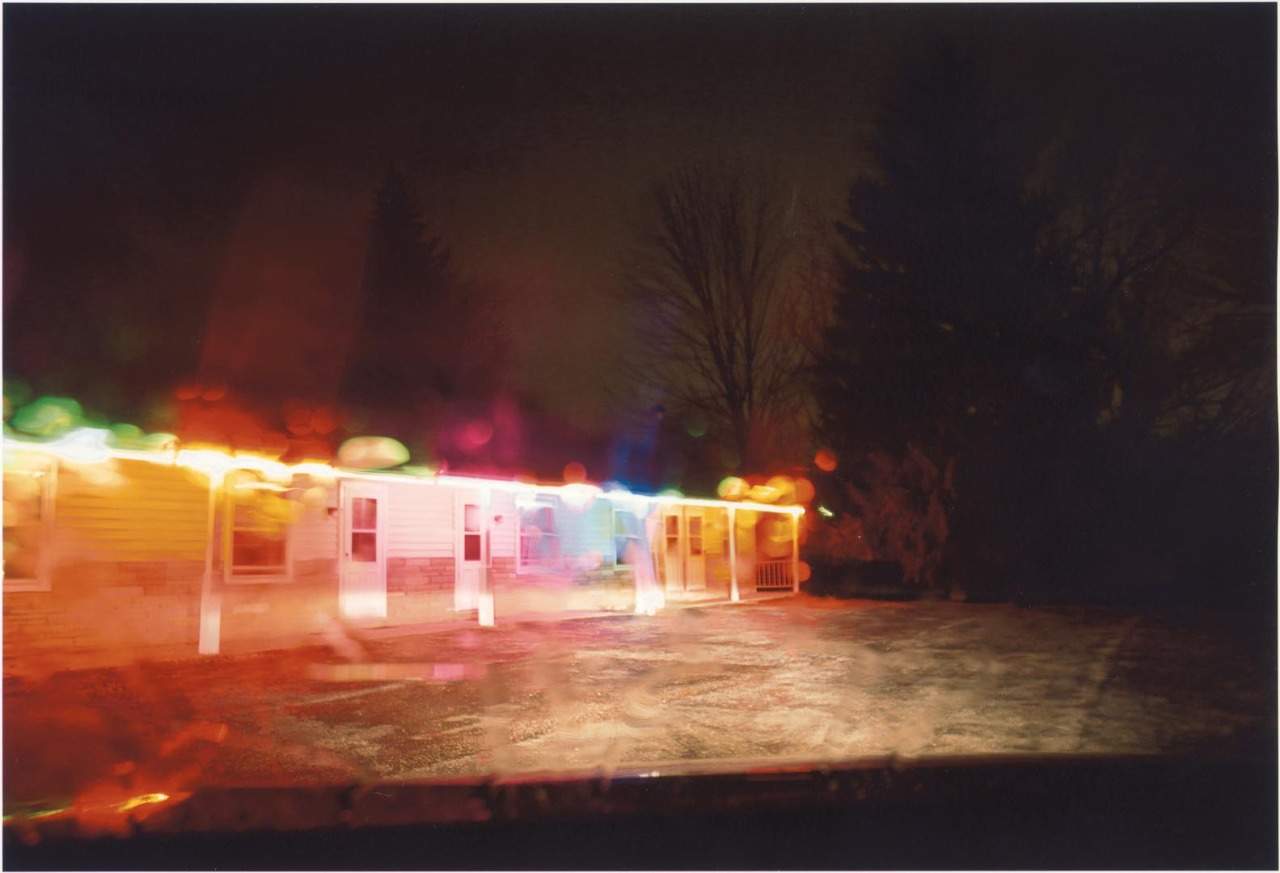

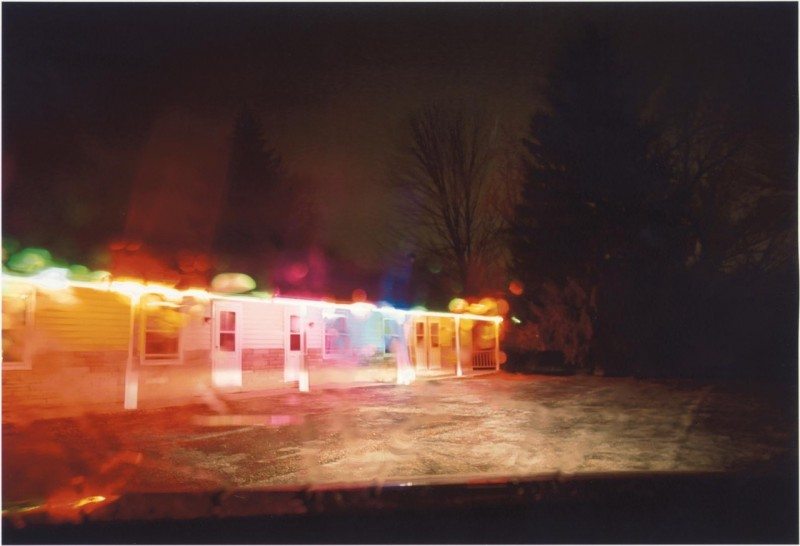

“Emmet Gowin once said to me, ‘photography is about position.’ I use this diagonal perspective a lot. There’s a vanishing point or a corner. In fact, I think there’s only one photograph I’ve made of a building that is shot straight on like a Walker Evans. When photographing space, it is useful to use perspective to draw the viewer into the frame. The diagonal line creates depth, and depth often works well in describing an environment. The diagonal lines extend your photograph into infinity somehow.”

Takeaway point:

Position is absolutely critical in street photography. As a street photographer you want to constantly look into the future.

You see your subject walking towards you from half a block away. You need to anticipate where they will be in about 30 seconds, and how you want to position yourself in the street to photograph them in a certain way.

For example, if you see an interesting subject coming towards you, you might want to identify a good background to get them against. Based on this information, you might stand near the curb and shoot them against a storefront or billboard.

If you want to fill the frame with your subjects, you need to position yourself in a way that does that. If you are too far away from your subjects, you need to step closer to your subjects. You need a closer position to them.

Also if you want to create intense images with a lot of energy and edginess, try to focus shooting head-on (instead of from the side). For inspiration, look at the work of Garry Winogrand or William Klein.

Furthermore, one of the strong compositional tools you can use to create a better perspective is diagonal composition.

12. Let your viewer fill in the blanks

One of the main places that Todd Hido gains inspiration from is cinema and film.

He describes when he is driving around the suburbs, he always sees scenes and dramas of imagined stories:

“When I’m driving around the suburbs, I see them as if they were a set where dramas are unfolding all the time. I’m setting the stage for an imagined story.”

I think as street photographers we can relate. We are trying to capture the beauty and drama of everyday life. The stories we capture aren’t factual nor are they “objective.” They are our own interpretations of reality— and we try to create this human drama through our street photography.

In Todd Hido’s “house hunting” project— he tries to create an imaginary sense of drama through the illuminated windows he captures. He describes the power of imagination— that the viewer fills in the blanks. This makes the images much more engaging:

“I haven’t shown anything actually taking place in the windows. Anything you think is happening is happening in your own imagination. The backlit curtains simply trigger that. When I’m photographing, I start to fill in the gaps of the story in my mind even though the viewer may not sense that story in the finished picture. I exaggerate certain details in the scene to give a sense of something beyond what’s seen.”

Hido also shares the importance of leaving certain details out. By showing too much of the scene or the story, it becomes boring. You want to leave the final interpretation up to the viewer:

“I purposely leave things out so that people can bring their own stories into view, so that the meaning of the image ultimately resides with the viewer.”

But is there an ultimate “objective” and singular interpretation? Definitely not. Each viewer will interpret your photos differently based on their personal life experiences, and how they see and experience the world. You don’t want your photos to be too obvious to your viewers:

“What I enjoy most is making images that are suggestive in this way, that have potential for being read with different meanings. I don’t want the story to be entirely evident.”

Often “not knowing” makes us more intrigued in images:

“When I don’t understand what’s happening, I’m more intrigued. Oftentimes what’s not shown is of more interest. It activates the sense. There’s a kind of pleasure in not knowing, in having to pay attention.”

Takeaway point:

Let your viewers fill in the blank for your images. Don’t make the stories too obvious to them.

Perhaps you can incorporate the “decapitation” method to your photos by intentionally chopping off the heads of your subjects. This will make the images more mysterious in the sense that you don’t entirely know the expression, mood, or the face of your subject.

Perhaps you can single out your subject, and photograph them against a background that has no context. This might make your viewer more intrigued by asking themselves, “I wonder where they are?”

Another way you can add more intrigue to your photos is to add shadows and silhouettes in your work. Photograph when there is harsh lighting (or during golden hour)— and try to photograph that obscures the face of the subject with the shadows.

Don’t make your street photos easy to interpret. Make it a puzzle— a riddle, which is ultimately more fun for the viewer.

13. Create ambiguity

Going along the previous point, create ambiguity in your photographs. Don’t offer too many answers in your images (suggest more questions). Todd Hido shares:

“Ambiguity is one of the finest tools for making art. In my way of thinking, images should raise more questions than they answer.”

Todd also mentions the importance of activating the desire of the viewer to know more:

“I want my photographs to make people wonder about what’s going on instead of giving it away. I’m not necessarily saying that when work tells you something directly, it’s a bad thing. But, I like when I have to ask, “What’s going on here?” As a photographer, I want to tell you just enough with the pictures to activate your desire to know more.”

Takeaway point:

Curiosity is a strong tool in photography. Like a good story, you want to draw in your subject with intrigue— and you want them to keep flipping the pages to find out what happens next.

In good mystery and detective novels, the book usually starts with a murder scene. Then for the rest of the book, you are trying to figure out who did it. If the first chapter of the book explained who killed whom, the book would be quite boring.

Treat the same philosophy to your photographs. Make it like a murder mystery— have your viewers wonder what is going on in your scene. Have your viewers identify the main protagonists, the drama, and have them try to uncover what is going on.

When I am looking through photographs, I love photographs that make me stop, pause, and wonder, “How did this photographer make this image? What is going on here?”

Additional ways to add intrigue to your photographs: shoot through windows, reflections, and add surrealism. Street photography isn’t about simply defining reality “objectively”— it is about creating your own subjective reality.

14. Add to the conversation

One of the major pains that I had in my photography for a long time (and still have) is identifying my own “style” or voice.

Ultimately I think everything we do is authentic and unique (we haven’t done it before)— but at the same time, we want to “add to the conversation.”

What do I mean by that? In academia— you need to do research in a field and create a thesis that hasn’t been done before. You don’t want to research things that people have already solved. You want to work on novel problems and find novel solutions.

Similarly in photography— you want to study the work of the masters, see the work that was done before you, and see how you can contribute to the work that has already been done.

“Adding to the conversation” doesn’t mean that you have to create 100% entirely unique work. Rather, you can remix and tweak projects that have already been done before. However, you still want to add your own unique twist and perspective on things.

Todd Hido explains how in his “house hunting” series he added his own twist and “added to the conversation.” People have photographed houses at night before him— but he did it differently enough which made it meaningful and unique:

“As I began to realize that my pictures of houses were ultimately about relationships and home and family, I also realized that this is what makes them different from the work of those who have photographed these kind of subjects before me. My more personal take makes my work very different than that of, say, Robert Adams or Henry Wessel. The three of us would make an interesting case study because we are all photographing houses at night but yielding completely different results.”

Hido shares how he differentiates his work from other photographers who photographed houses at night such as Robert Adams. The main difference? Hido’s work is much more subjective, while Adams’ work is much more objective:

“In ‘Summer Nights’ (1958), Robert Adams photographs the same style of neighborhood that I grew up in and that I still photograph. But somehow he can photograph a house at night and I can photograph a house at night and they’re not the same thing. They almost don’t even relate to each other in some odd way. Adams takes a more objective stance, while my pictures are more subjective. This goes to show that not everything has been done before. There’s always room to add to the conversation.”

The ultimate take-away from Hido is that “there’s always room to add to the conversation.” Don’t let the fact that certain photography projects have done before get in your way.

I have a friend named Charlie Kirk who is currently doing a long-term street photography project on Istanbul. Alex Webb has already photographed Istanbul— but Charlie decided he wanted to do it differently. Charlie opted for shooting it both in black and white and color (while Alex Webb shot it all in color). Charlie decided that he wanted to make it more socio-economic/political, while Alex Webb photographed mostly scenes in the streets. Charlie shoots with a 28mm, while Alex Webb shoots with a 35mm. It is different enough, yet Charlie is adding to the conversation (instead of just creating another color street photography series of Istanbul).

However even Todd Hido has to remind himself the importance of going out and doing work (and not getting discouraged):

“Sometimes I have to remind myself of this. There are a million ways to talk yourself out of making your work, and saying to yourself that it’s already been done, is a big one. Not everything has been done before. Go and do your work. You can see where it leads and how it fits once it’s made.”

Takeaway point:

Whenever you decide to work on a project, don’t let the feedback “it’s already been done before” get in your way. However at the same time, don’t totally ignore it.

Rather, extensively study the work that has already been done before— and see how you can do it differently.

For example, one of my long-term projects is my “Suits” project. There have been tons of other projects photographed on suits before— but what makes mine different? I take a much more sympathetic view on guys wearing suits and working corporate (rather than other projects, which seem to be much more negative and condescending towards suits). I also am working mostly with flash (haven’t seen other projects done in this way).

I am also working on a long-term photography project on America, titled: “Only in America.” My project is currently very similar to work that has already been done before (I am getting my main source of inspiration from Zoe Strauss, Stephen Shore, Lee Friedlander, and Robert Frank). However the way I want to differentiate the project is for the series to have a greater variety of images— for it to be more based on street portraits and urban landscapes. Admittedly the project is still in its infancy and hasn’t found its own voice yet— but I am still working hard on differentiating it from other projects that have come before mine on America.

My advice to you when working on projects is this: stick with it, don’t give up, be persistent, become knowledgeable about the work done before you, and try to be you.

Don’t try to copy the work that has come from before you. Find inspiration in the work that has come before you, but photograph what you naturally are interested and drawn to. Don’t just makes images because you think other people will like it.

Make a project that you would appreciate at the end of the day (and whether other people like it or not is up to them).

15. Harness repetition and variation

One of the creative tensions a photographer faces is this: creating a unique body of work (that is easily identifiable and has a “style”) while also avoiding boredom.

So how do you combine both of these things?

Todd shares this dilemma he had of not always having new ideas, and stressing about the next projects he would work on:

“I used to get really freaked out when I didn’t have new ideas, thinking, “Oh my God, what am I going to do next?” I thought I had to change everything, and of course, you can’t just go and do that because you can’t change yourself.”

However Hido remembered the insight that it is okay to keep doing what you are comfortable for a while. You don’t need to always do something new. He says in the end of this excerpt: “repetition is just part of the creative process”:

“I keep this list of rules for art students in my office, the same list that John Cage kept in his studio. They’re by Sister Corita Kent, and the first rule is, ‘Find a place you trust and then try trusting it for a while.’ It’s okay to stay in the same place for a while and to trust the desire to do so. I’d go to the same suburbs and make pictures of houses at night with lights on. I’d see that a picture was really good and then make another one to see what happened. I’d go back again and again, making pictures in the same places. Slowly but surely the work evolved. I don’t think our human nature lets us truly repeat ourselves. Repetition is just part of the creative process.”

Todd continues by saying in photography— there are times it is important to repeat yourself over and over and have consistency with your work:

“Frederick Sommer used to say a lot that ‘variation is change.’ That’s the thing about photography that’s so curious. There’s something essential in doing the same set of actions over and over again. It’s a kind of ruminating.”

However he does mention the importance of avoiding too much comfort— you want to avoid boredom. Sometimes small variations will do the trick:

“There’s a comfort and consistency in the repetition, but it’s not too comfortable. You’re not bored. There is still something sustaining your interest, pulling you along. You have to trust that you will come up with something different, arrive somewhere new in the process. It may start with making a picture of a house that is orange instead of blue.”

Todd continues by sharing the dangers of repetition— and how it can be harmful to us:

“Repetition is your friend and also your enemy. While you want your work to be consistent, to have a style, you’ve got to strike the right balance between consistency and monotony once you’ve been working on a project for a while. I remember when I was heavily into photographing the houses at night, there came a point when I was really conscious that the pictures could not all be taken on foggy nights; I couldn’t rely on the fog to be the seductive part.”

Todd shares the importance of adding variation and variety to his project”

“I already had a number of those shots and needed to introduce more variation. I had to go out on clear nights also. I needed to go out to the outskirts of the suburbs and take pictures. When I’d hit a critical mass of pictures of houses, I would go out and shoot apartments. I wasn’t making huge changes. This type of attentiveness to repetition and variation brings me change.”

Takeaway point:

When you get bored on working on a certain project, you often don’t need to make huge changes. Sometimes all you need are small and subtle variations to get you feeling creative again.

So for example— let’s say you are interested in shooting “street portraits.” But after a while, shooting portraits of people’s faces on the streets don’t interest you. This might not necessarily be a sign that you stop shooting portraits all together. Perhaps you just need to switch it up.

Perhaps you can start off by shooting different types of faces. If you are mostly drawn to old people, you can start photographing more young faces. If you shoot most of your portraits in black and white, perhaps try to switch it up by shooting in color.

One of my favorite street portrait series is by Bruce Gilden. His compositions, framing, use of color and the flash is consistent, and his subjects are all quite grungy and gritty characters. But there is still a variety in the faces and expressions that he gets.

So there are many ways you can incorporate variety and consistency to your work. You can perhaps use a variety of cameras in shooting similar subject matter. Or vice-versa: you can use just one camera and one lens to photograph different types of subject matter.

Ultimately the key is this: you want to avoid boredom. Try to stay as consistent as you can with your work, and follow your curiosity.

16. Don’t follow what is popular

Trends come and go. The funny thing about trends is that when you try to follow a trend, it seems to go away quite quickly. As soon as you try to jump on the bandwagon, it has already left.

So rather than looking at what is popular and trying to imitate it— just follow your own intuition. Todd Hido encourages us to avoid what is popular below:

“You can’t look at what’s popular at the moment and then simply go and repeat it. That’s a recipe for disaster. You’ll make empty art if you try that approach or only care about success. You’ll always be chasing something, because trends change constantly. One minute, cold, crisp and conceptual German photography is the bee’s knees, and then the next minute, emotional documentary work is hot.”

Todd shares his own personal experience— that while Todd is personally drawn to shooting more subjective subject matter (with emotion), he was encouraged to take a more objective and cold stance. This didn’t jive well with him:

“When I started my career it was very much the era of theory and post-modernism. Subjective emotion and beauty were not on the radar. It was a cliché’ to have anything to do with that, I was encouraged to shoot from a uniform distance, to use a more neutral color palette, to work more conceptually, and take a more objective stance— basically to work like I had worked with the Bechers in Dusseldorf.”

Todd shares how he ignored that advice— and followed by making the types of photographs that he wanted to make:

“But that advice, well meaning as it was, didn’t sit right with me. Those weren’t the kinds of pictures that I wanted to make, and I knew better than to follow that path. There are always going to be way too many people giving you their opinion. When you do get advice, it’s important that you, as an artist, know what to leave and what to take on and consider. You can’t become somebody you’re not.”

Todd Hido doesn’t tell us to simply discount all the feedback and advice we get from others. Rather, listen with an open heart— and know what to take (and know what to ignore).

What is Todd’s ultimate advice in finding your own vision (and not just imitating others, and what is popular?) Follow your instincts:

“It has served me well throughout my career to follow my own instincts. I learned early on that I should just do what I really wanted to do, and I wanted to keep my work emotional and subjective. Really, I couldn’t do anything other than that. I can honestly say that even if I had not achieved any level of success with my work, I would still make it because I need and want to make it.”

Takeaway point:

Follow your own instincts. Photograph what you really want to photograph. If you want to make subjective and emotional street photographs— follow that path. If you prefer more visual composition and geometry— follow that path.

Another piece of advice: only make the type of photos that ultimately make you happy. Don’t worry about making photos that are “popular” or which you can sell.

You never know what kind of photos will please others. But you know what kinds of photos please you.

Aim to please yourself above everything else with your photography. The rest will follow.

17. The color of emotion

What I really love about Todd’s work is the emotion, color, and mood of his images. But Todd doesn’t just shoot color for the sake of it— he is very conscious about the emotions that arise from colors:

“Another primary thing that conveys feeling in photographs is color. Blue will almost always be read as cold to us, especially in landscape. Green represents growth or sickness, depending on the hue. Colors bring their own meanings and moods to a picture.”

Also when it came to his photography, Todd Hido wasn’t interested in capturing an objective view of the world. Rather, he wanted to create an imaginary world:

“When I first started photographing I was shooting black-and-white. I’d never really shot in color because I didn’t have access to a color darkroom and whenever I had worked in color, I sent the negatives to a lab, and they would always create a neutral print. I wasn’t interested in that; I found the print to be too real. There was something about it that too closely referenced the real world instead of this imaginary world that I was trying to create.”

Todd also shares a story when he took a black-and-white darkroom printing class with Roy DeCarava. Funny enough, Todd initially wanted to do a color darkroom printing class (but there were scheduling conflicts) and he ended up getting stuck with Roy DeCarava instead:

“I would bring my print out of the darkroom in the wet tray and show it to Roy. Each time he said, ‘Make it darker. Make it darker.” I saw that though pictures turn out a certain way in their raw negative form, you can push them in a whole different direction in the printing. That’s largely what I’ve done in the darkroom for years.”

A lot of photographers tell you that you have to get the photos entirely in-camera. While I do encourage street photographers to try to get as good as a composition in-camera (without cropping)— ultimately you don’t want to only post raw JPEG’s to the internet. There is a certain amount of post-processing you need to do to your photos to convey a certain emotion or feeling.

Todd also doesn’t get his photos straight out of his camera— a lot of emotion is created afterwards in the darkroom:

“My pictures don’t materialize into form straight from the camera; I choose the way they look and feel afterward. Taking the picture is just the starting point. Often my contact sheets look nothing like the final print. I’m very manipulative in the darkroom, and now, on the computer.”

Todd shares the importance that he learned in the darkroom printing class with Roy DeCarava— that the way you make a print is totally subjective:

“That one-week workshop completely influenced my whole career—learning that a print can be interpreted to look any way you want it to look. There is no right way. It’s totally subjective.”

Todd also shared another thought when he first started experimenting printing in color— “What would Roy DeCarava say?”

“When I started experimenting with printing in color, I thought about what it would be like if Roy DeCarava was standing outside the darkroom giving me advice. He might say, ‘Make the color totally gone.’ Or, ‘Make the color super blue.’”

Ansel Adams once famously said, “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.” Adams spent tons of time in the darkroom, manipulating his negative to achieve the tonality in the black and white landscapes he captured.

Todd Hido also does this in color— he makes the photos feel the way he wants them to feel (by adjusting the colors in a certain way):

“I was never really instructed in how to print in color, so I adjusted the colors in my photographs to be whatever I felt they should look like or convey. The way I use color is very subjective.”

What kind of colors does Todd Hido ultimately like? He shares the emotional thoughts behind his colors below:

“I like colors that are more muted and softer than in reality. I’m not married to reality; I don’t feel I have to faithfully describe a place. I add my own emotional content in the choices I make in the printing process. Color absolutely sets a mood. There’s no question about it.”

However at the same time— he wants to make his colors not too crazy or wacky— he wants to make them “believable”:

“When I’m choosing the colors, anything goes, but I still want the picture to feel like it could be real, like it could have happened.”

Takeaway point:

When it comes to street photography and color— don’t just photograph colorful things for the sake of it. Think about how color adds a certain mood.

If you want your photographs to convey a more subdued and neutral tone— perhaps stick with cooler colors (blue, green, violet). If you want your photographs to feel more intense and energetic— embrace colors like red, orange, and yellow.

Also know that the colors don’t have to be exactly how you saw it. When you are shooting with color film— the film doesn’t exactly look like how you captured it in reality. The film interprets the scene differently and processes the colors in a certain way.

So when you are post-processing your photographs in color, make your photos look the way you want them to look.

However I do encourage you to try to stay consistent with the way you process your colors (at least within a certain project). If the majority of your photographs are a warm tone, perhaps try to make them all warm. Try to stick with one type of film for a project.

If you are working in digital, perhaps you can create a certain preset for your photographs. Then try to stay consistent with that process.

18. Make lots of small decisions

When you are working as a photographer, there are many decisions you are going to face. Below, Todd Hido shares some of the challenges you might face:

“Making decisions is one of the most critical things in art making. You’re always in a state of deciding. What camera am I going to use? Am I going to shoot this in black and white or color? Horizontal or vertical? Am I going to print this in Inkjet or Lightjet?”

Todd Hido shares the importance of making lots of small decisions in order to create art:

“Larry Sultan used to say that the act of making art is the act of making many, many, many small decisions. Each question you encounter can lead you down a particular path.”

But how can we be sure that the small decisions we make are leading us in the right direction? We need to have faith— and work forward in small steps:

“If you can be decisive and move forward through the decisions step by step, you’ll be more successful. The real question is: What’s right for you right now? And realizing what’s right for you changes over time.”

Takeaway point:

Your photography will change and evolve over time. Don’t feel pressured or stressed to make huge long-term decisions regarding your photography or projects.

Plan your projects to take years, but try to stay present-oriented and make the small day-to-day decisions that affect you.

For example, you might have a grand image in your mind to do a street photography project of America. But instead of worrying about all the long-term details like getting an exhibition, getting a book, or marketing your project— focus on the small details (in the present moment). Figure out what camera and lens you are going to use. Figure out if you want to shoot it in black and white (or both). Figure out what cities or states you would like to visit.

Keep moving forward with these small decisions — and keep your eyes focused on your long-term goals.

19. Create parameters

I believe that creativity needs restrictions. Sometimes by creating parameters, you will become more creative. Todd Hido explains:

“There are no rules. But sometimes you need parameters. They could be conceptual. Sometimes, there’s value in just naming what you’re doing at the moment as a concept: “I photograph houses at night.” You can then add to the concept, like, “I also create a mood. I look for moody things at night.” Or, “I only photograph on cloudy days.” The concept can change and evolve. You can always modify it at any point because it’s yours.”

Takeaway point:

If people ask what kind of photos you make, perhaps you can start off by saying “I shoot street photographs.” This is creating a parameter— by saying you shoot “street photographs” it means that you aren’t as interested in photographing landscapes.

Over time your photography will probably become more specific. So instead of saying that “I shoot street photographs”, you might say “I shoot street photographs of people which are visually complex and multi-layered.” Or you might say “I shoot street photographs of mostly people’s faces.”

Know how to define yourself as a photographer— but know that your personal definition of your own photography can (and will) change and evolve over time.

20. Shoot whatever moves you

When you’re out shooting— you want to photograph what excites and moves you. Don’t photograph what you think others will think is interesting. Photograph what genuinely excites you. Todd Hido shares some of these lessons:

“Your parameters should be flexible enough, though, that you can still just shoot whatever moves you. Photograph whatever catches your eye, whatever gets your ass out of the chair to go photograph.”

Often we have a self-critic in our head that tell us not to take a certain photograph (because it might be boring or stupid). Ignore that voice. Take the photograph anyways, because you never know how the photograph will look (unless you try photographing it):

“Take the picture and see what happens, because you never know. Sometimes the world looks different in photographs. Like Garry Winogrand said, “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.” This leaves the door open for surprise. Often with the unexpected, with contradiction, there’s growth.”

Takeaway point:

I think when you’re out shooting street photography, you should follow your gut. Photograph what personally makes you happy, excited, or scared. Channel your emotions into your shooting process.

Also don’t have regrets when you’re out on the streets. It is better to photograph something (and edit it out later) than never taking the shot. The worst-case scenario is you have a boring shot. The best-case scenario is that you will make a brilliant shot.

21. Take short trips

Many of us get bored and lose creativity when we spend too much time at home. What is Todd’s advice to this problem? Just take a shot trip out of town:

“I also started making shorter trips out of town— to Ohio when I could and also to places closer by that spoke to me. A two-hour plane ride could take me to eastern Washington, for instance. I love working this way because sometimes it’s hard for me to focus on my work at home; there’s too much going on. I may want to leave the house at 10:00, but I end up leaving at 12:30 because I answer the phone and get pulled into other things. I’m a single father of twins. It’s not always possible to be creative whenever I want. That’s not real life. If I can get away for a short trip, I am not only transported to a different location but a different mental space; and I know my time there will be dedicated to taking pictures.”

Takeaway point:

Sometimes you need a small little change of scenery to re-inspire you. And it doesn’t have to be far. That little trip can just be a 30-minute or an hour drive from your home. It can be a part of town that you normally don’t go to.

Try to inject novelty and variety into the locations you shoot street photography— and it will be enough inspiration you need to get into a new mental and creative space.

22. Knowing when to stop

Todd Hido focuses on projects. But many of us photographer face this dilemma: how do we know when to end a project? Todd Hido shares his own opinions on this matter:

“How do you know when you’re doing with a project? I kept on making the landscape pictures because I was still captivated by the subject. I wasn’t making them for art’s sake; I was making them because I needed to make them.”

Todd gives us this advice: make photos because there is a part of your soul, which forces you to make them. Don’t photograph for the sake of it— photograph because it scratches that itch within your soul.

Todd also gives us further practical advice: when you’re too lazy to make photographs of a project (and have lost the passion for it)— you should stop:

“And so I’d say you’re done with something when you stop getting out of your car to photograph it, or when you stop getting your camera out of your bag to take a picture. That’s when you’re done: when you’re not compelled to shoot the subject anymore.”

Takeaway point:

When you shoot street photography, you should enjoy the process. Don’t photograph because someone forces you to do it. Photograph what excites and stimulates you.

If you are working on a project, you do it because there is something that compels you to do so. You don’t need to force yourself to work on a project. It is effortless (like the Taoist concept of “wu-wei”— action without action).

So when you are shooting a certain project or subject matter, follow your heart. If you fall out of love with a project, perhaps you should discontinue the project (or figure out how to work on it in a different way).

23. Shoot subconsciously

One of the great quotes I got from the Swedish photographer Anders Petersen is: “Shoot from the gut, edit with your brain.”

What does Anders Petersen mean by that? He means the following: when you’re out shooting on the streets, shoot with your intuition and guts. But when you’re at home in front of your computer, edit with the more analytical side of your brain.

Todd Hido mirrors the same philosophy— he doesn’t over-analyze his photographs when he’s out making images:

“I don’t analyze my photographs like this while I’m shooting. Making and analyzing are completely different processes.”

Hido does admit that you need some analysis when you’re shooting— but not that much:

“You do have to examine things a little bit when you’re making— there is some conscious recognition in wanting to take a picture— but as much as you can you should just make. See, respond, and click. And the more you click, probably the better.”

Hido also shares the importance of harnessing your subconscious when you’re working:

“Much of what happens in a picture is subconscious at the time I make it. I’m really seeing what’s there later, when a picture is done. Joan Didion puts it this way, ‘I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I see, and what it means. What I want and what I fear.’ I feel the same way about photography. I learn things from my work about what I’m thinking. My mind is way more sophisticated than I realize. Sometimes, I pull things out of my hat while I’m working and later I think, ‘Whoa, where did that come from?’”

Sometimes the best thing of photography is that the results are totally unexpected (in a good way). When we make photos, we never 100% sure know how they are going to turn out. That is the fun, mystery, and excitement of photography:

“The act of photographing can bring inner things to the surface. I’ll look at my pictures when they’re finished and realize they are really touching on something deeper. One of the great pleasures of making photographs is being surprised by the results.”

Takeaway point:

When you’re out shooting on the streets— don’t overanalyze your compositions, frames, or instincts. Shoot from the gut— do what feels right. If you spend too much time over-composing your scenes, you will probably not get any shots at all. I try to avoid being a perfectionist when I’m out shooting. I just try to get the shot.

However I am much more anal and perfectionistic when I’m editing (choosing my best images) on my laptop.

We have very little control when we’re out shooting in the streets. All we can control is where we stand and when we click the shutter. We only have control over position and timing in street photography. We can’t control the light, the clothes people are wearing, or what the buildings look like.

However what you ultimately have control over is whether to keep or ditch a shot. The editing process lies 100% in your control.

24. People don’t have to see all your photos

My friend Charlie Kirk recently wrote a list of 101 things he learned from street photography on it he says, “If you shoot film you’re a photographer, if you shoot digital you’re an editor.”

It is a great quote— because it identifies the problem that many of us digital photographers have: we take so many photographs and have a hard time deciding which images to keep (and which to ditch).

But remember this: we don’t have to show all of our photos to the public. It is okay to let some of our photos die on our hard drive (or rolls of film). Not every image needs to be shown.

Todd Hido shares this concept below:

“Just because I take a picture doesn’t mean that somebody has to see it. Much of the time, the whole idea is to make pictures that nobody will see.”

How will we know if we get a good photograph that is worth showing? For Todd Hido, good images have “a certain power or electricity to them” and are generally personally meaningful to him (and others):

“There are so many pictures that when you snap the shutter, that’s the end of their existence. It’s done. It never comes to life. You see it on a contact sheet, and you don’t even look twice. The good pictures all have a certain power or electricity to them. For a picture to have a long life it has to speak to me, have some meaning for me. And then, of course, I hope it contains enough space to hold a range of meanings for others. You might have to take 10,000 frames to produce 500 really good pictures.”

But does every photograph we take have to be for a project or have to be “serious?” Not exactly.

Todd Hido takes a lot of random photos in his daily life — but his organization comes mostly through editing them afterwards:

“When you see my work in a book or an exhibition or a presentation it may seem tightly organized and rigorously consistent. But that’s not representative of my day-to-day life as a working artist. If you look at my contact sheets, I am all over the place, as are most photographers really. If I see something I like, I take a picture, and that takes me down many different paths at the same time. The organization of one’s work comes later. You have to just shoot and you know you’ll figure how it all comes together later.”

Takeaway point:

In your daily life, you will often take a lot of random photos that nobody will ever see. Don’t feel anxious or self-conscious about this. It happens to all of us as photographers.

I think we should also work hard to be stringent self-editors of our work. Only show your best, and create good edits of your work. Less is more.

And it is okay to take photos that are just personally for yourself (that nobody else will ever take). Take fun family snapshots, photos of your food, or that HDR photo of a sunset. Enjoy the process for yourself— and also work hard to make images that will please others too.

25. On simple gestures

Todd Hido is famous for photographing houses at night, dreamy landscapes, and also emotional nudes.

What does Todd Hido look for when he’s shooting portraits of people? He looks for subtle hand, eye, and body gestures:

“Any time you’re working with a person as a subject, be it a portrait or a nude, very simple gestures become fascinating. You don’t need to go for grand poses; subtle hand gestures and expressions of the eyes and mouth say it all. We are such complex communicators with our bodies that the slightest movement can alter the meaning of a picture. If a picture lowers or raises their eyes, it changes everything.”

Takeaway point:

In street photography, I feel that the most powerful images are the ones with strong emotions. How do you convey emotions in street photographs? Just look for the subtle gestures.

The gesture can be the position of a subject’s eyes, the gesture can be a hand or leg gesture, or it can be a facial gesture.

Don’t just photograph people with blank expressions and their hands by their side. Wait until they have those subtle gestures— then try to capture it.

26. Making pictures that speak to you

When you’re making photos of others— you’re really making portraits of yourself.

I think as street photographers we don’t have some sort of moral obligation to show “the truth” in our images (like documentary and photojournalists do). We create our own “truths” through our photographs. We create our own subjective realities.

Todd Hido shares his perspective:

“When I’m photographing people, the kind of person that they are in reality isn’t relevant. It doesn’t matter if they are a nice or mean or funny or cool for the picture. They’re an actor, a stand-in for a person or situation from my history. So I’m immediately able to divorce myself from any need to record them as they are. I’m not like Bruce Davidson in East 100th Street, photographing people to whom I might have some responsibility to tell their story faithfully. I don’t need to do that. What I’m interested in is making a picture that speaks to me, that tells me my own story in a new way.”

Takeaway point:

When you’re photographing people, try to tell your own story (through them).

27. On creating fiction

Another analogy when creating images is to think about “creating fiction.” Todd Hido shares the importance of crafting imaginary stories:

“You can create a fiction, but maybe you’re telling a story that’s real in the end.”

Sometimes fiction is a more accurate representation of reality (than non-fiction):

“Picasso once famously said, ‘Give a man a mask, and he’ll tell you the truth.’ I think that happens with my work. These are real stories: mine, a friend’s, or a model’s. Sometimes they are stories that I hear on the news.”

Todd Hido also shows how although the camera is supposed to capture reality in a factual way— it tells lies:

“That’s one of the gifts of the medium. The camera is a magical machine that can record something that’s completely true, and at the same time, a total lie— simply by stopping at the wrong moment. Subjects might look like they’re crying when they’re laughing, or look drunk when they just have their eyes closed. The point is, photography can describe everything in the frame in great detail, but the meaning of what’s described is ambiguous.”

The ultimate question that matters is what you are trying to say as an artist:

“Whether the photograph is true or not doesn’t matter. What maters is what you want to say as an artist to the world, even if the meaning eludes you too. It’s engaging to purposely make a picture in which the truth is slippery, that resists a definitive meaning, that stays in the zone of ‘is it real, is it not real?’ I like to work in that zone.”

Takeaway point:

Ask yourself, “What am I trying to say as a photographer and an artist? What makes my subjective view of the world unique from others? What kind of fictitious stories am I trying to tell through my images? How can the viewer learn more about who I am as a person through the people I photograph?”

To get inspired to make better stories in your photos— don’t just look at photographs. Watch films, read novels, and study stories. Figure out what kind of fictions turn you on, and try to replicate that through your photography.

28. The details are crucial

There is a saying: “The devil is in the details.” The details matter.

In street photography, I am always looking for a “cherry on top” for certain images. It is often the small details, which make a good street photograph into a great street photograph.

Todd Hido shares the importance of small details in photography. The details can be the place, the background, or small elements in the frame:

“You can have an amazing story to tell, but you have to get the setting right. Location is everything. The place is part of the story, and the details are crucial. If the place isn’t right, it doesn’t matter what’s going on in the picture. When you’re shooting a portrait of somebody, if you don’t have the right background, or if you haven’t moved the stuff out of the way that isn’t part of the story, the photograph is not going to convey what you’re trying to say. When I’m shooting, all I see at first are the potential errors in the background; I can’t even see the person until I fix all that.”

Takeaway point:

When you’re editing your own images— ask yourself, “What are the small details which make this a truly great photograph?”

A small detail or “cherry on top” can be someone’s facial gesture, their hand gesture, a certain person in the frame, a certain color in the frame, or a certain “happening” in the frame.

Search for these small details both when you’re shooting (and also in the editing phase).

29. Let randomness occur

You can’t predict everything when you’re out on the streets. Street photography is one of the most random and unpredictable genres of photography out there. We never know what we’re going to get until we actually go outside and hit the streets.

Therefore learn how to embrace randomness in street photography— it often makes a photograph much better. Todd Hido shares how he embraces randomness in his photographs to make them more interesting, unique, and “believable”:

“One of the things I learned from Frederick Sommer is that if you’re trying to make a still life and you arrange every part of it, it’s not going to be any good. The same could be said about a portrait. You have to create an environment where random things can still occur and then recognize when to take the picture. Things can very easily look contrived or self-conscious within a photograph. If you predetermine everything that will happen in front of you, the photograph will look too particular.”

This is why we often hate staged photographs. They feel too fake. Too artificial. Not interesting. Boring. Stiff.

However as a street photographer you can stage your scene. You can choose a certain background you find interesting, or shoot during a certain time of day when the light looks a certain way. But then what happens with the subjects is totally unexpected.

Similarly when you’re shooting street portraits (and asking for permission)— the gestures and ways people react to your camera is often unpredictable.

So embrace this randomness. Todd Hido continues:

“So you set the stage so something natural and unanticipated can occur. Then the picture will have an authenticity to it and that is really important. I don’t like things that look super-staged. I find images more compelling when things are more gritty and realistic. I don’t care if you stage it, just don’t make it look staged.”

Takeaway point:

I personally don’t care if a street photograph is staged. I am more interested in how I interpret an image, and if it excites me (than if it were truly “candid.”)

I also don’t feel that just because a photograph is candid that it is intrinsically “better” than a staged photograph. Some of my favorite photos are either staged or manufactured (like the work of Philip-Lorca diCorcia who stages his subjects to pose and look a certain way).

Ultimately you want to make interesting images. So embrace randomness on the streets and avoid making boring photographs. If you’re going to stage your street photos, at least make them look “unposed.” Furthermore if someone ever asks if your images are staged, don’t lie— tell the truth. Many of my street photographs are shot with permission and staged, but don’t necessarily look so. Therefore I have no problems telling the stories and the “truth” about my images if anybody asks.

30. Photograph the in-between moments

We all generally think that a posed photograph of someone is cliché. We hate it when people put up the “peace” sign or put on their “Facebook profile face.” We are striving to capture “authenticity” in our subjects, and one of the way to do this is to photograph the “in-between moments.”

Geoffrey Dyer calls this the “unguarded moment” – when the subject of a photographer drops his/her guard. In these “in-between moments”– you get an inner glimmer or glimpse into the mind and psychology of the subject.

Todd Hido talks about a photograph of Marilyn Monroe during one of these “in-between moments” and when Richard Avedon was able to capture something deeper about her psyche:

“There’s a really wonderful Avedon photograph of Marilyn Monroe taken in one of these in-between moments. It’s one of my favorite photos of all time. The story behind the picture is that when Monroe said, ‘Are we on?’ Avedon said, ‘No.’ And that’s when Avedon snapped the picture. In that moments he doesn’t have her guard up— she doesn’t have her happy face on, she isn’t being an actress, she is just a person who is lost inside her soul.”

Takeaway point:

When you’re shooting street photography– you are striving to capture those “in-between moments” and those “unguarded moments.”

I often ask to take a photograph of my subjects, and ask them to look straight into my lens. However the problem with this approach is that the subjects often come off as really stiff and awkward– and they generally don’t have interesting expressions or looks.

One strategy I will employ to have them loosen up is to just start chatting with them. I will ask them how their day is going, where they are from, or anything about their background or personality. Then the moments that the subjects start talking, they drop their guard (totally become unaware of the camera) and then some inner glimpse of their character comes out.

Another strategy I use if I am either caught trying to take a candid shot (or when I’m asking for permission) is to tell my subject, “Pretend like I’m not here– just keep doing what you were doing before I was here.” Funny enough, most people will laugh it off and then actually begin to ignore you– and continue to do what they were doing (before you saw them and wanted to photograph them).

31. On pairing images

One of Todd Hido’s great skills is book making. In this excerpt below, he talks about the magic of pairing images in a book– and how you can create new meanings through this process:

“One of the most magical things about photography happens when you place one picture next to another picture to create new meanings. When you see a picture of a person and another of a place your mind automatically fills in gaps as if they’re connected.”

Hido continues by sharing how our minds follow a plotline or a story like in cinema:

“In a classic cinematic approach, you would go down a road, meet a character and understand that’s where he lives. And then in the next scene, you understand that the interior is inside that house. If I put a picture of the outside of a hotel with a picture of a woman on a bed— boom— I’ve given you enough material to create a story. If you take a picture of a rainy cold, dark moment, and then you put that picture next to a portrait, it will impact how that person is understood and will set the tone for understanding the situation.”

When it comes to telling a story, it isn’t the pictures themselves that make the story. Rather, it is in the spaces in-between the photographs that create a lot of the meaning:

“Something happens in the space between pictures when you string them together. They automatically set a narrative in motion in our minds.”

Takeaway point:

When you are putting together a book or a project (and want to create a narrative)– think about how your images play out like a movie or a story.

Therefore think carefully about the sequence of images in your project (which image is the leading image, which image follows that, and what images to end the project with) as well as the edit of the project (which images to keep and which images not to keep).

Also the secret to creating a narrative is creating some sort of space or ambiguity in-between the pictures. Let your imagination play in the in-between moments; don’t feel the need to explain every single scene.

32. On creating narratives

Todd Hido shares with us more information in terms of how to create a narrative and the importance of person, place, and emotion:

“It really doesn’t take too many different components to create a narrative. There are three basic elements: person, place, emotion. Sometimes I’ll supply actions or the aftermath of actions in my work.”

We don’t always need to make uber-complicated stories. Sometimes the most honest and direct stories are the best. But in Todd’s work– he is looking to create complicated stories full of meaning, nuance, and mystery. By adding the perfect mix of people, places, and emotion– he creates projects that allow complex stories to emerge:

“You can do almost anything with these few fundamental components. You can tell a really complicated story, and that’s what I’m after. I’ve loaded the deck for meaning to occur.””

Takeaway point:

In street photography, think of how you can incorporate the three elements of creating a story: people, places, and emotion to your work.

People: Identify the right subjects you want to photograph. What kind of subjects do you want to photograph? Why do you want to photograph them? Are you looking for plain and ordinary people on the streets? Or are you looking for “characters?” Are you trying to photograph a certain type of people (for example people in business suits) or a certain demographic of people (old people, young people, or Asian people?) How will the people you select play into your story and narrative– who is going to be your protagonist, their supporting actor, and the enemy?

Place: If you want to create a story, where do you want the story to take place? Are you doing a project in the suburbs of California, the streets of New York City, the back alleys of Paris, or the mountains of Tibet? The location is absolutely critical– because it transports the viewer to a certain place they can identify with, and imagine the actors interacting at that place. So when you are working on a project, don’t only take photographs of people– try to do “environmental portraits” (photographing people with the background they are in) or just photograph landscapes of the setting in which you want your viewer to be transported to. So if you’re doing a project on Tokyo, perhaps take some photos of the skyline of Tokyo to give people a sense of place where the action is happening (don’t just take close-ups of the people).

Emotion: Probably the most important puzzle-piece of making a great story or narrative is having strong emotion. A street photograph without emotion is dead. As human beings, we are highly social and emotional creatures. When we are watching a movie, reading a book, or watching a play– we crave drama and emotion. We want action, twists, turns, surprises, and plot twists. What kind of stories do people hate the most? Boring ones. So think of how you can inject more emotion, drama, and suspense into your images. Look for facial gestures, hand gestures, juxtapositions. Shoot with your heart when you’re on the streets and empathize with your subjects.

33. Master the basics; eliminate variables

The problem that a lot of beginner photographers make is that they try to do too much in the beginning. For example, they try every single camera, every single lens, every single film, every single setting, every single genre of photography, etc.

However one of the best ways to get really good in photography is to eliminate variables– and master the basics. Todd Hido explains this concept below:

“If you’re still learning your way around, you have to master one thing at a time, eliminate the variables, before you can branch out. Otherwise you’re just wasting time. You find a film that works and you keep using it until you’ve mastered it. You find a lens that works and you continue to use it until you no longer have to think about it.”

Takeaway point:

I don’t think you need to only pursue one type of photography or use one camera/one lens for the rest of your life.

However I do agree with Todd– you should try to master one setup or genre before you move onto the next (or at least feel comfortable).

So for example if you’re new to street photography (or intermediate) – stick with one camera and one lens and perfect it before moving onto the next thing. It took me about 3 years or so to get really comfortable shooting with a Leica rangefinder (especially shooting on film)– and now that I am quite comfortable with it, I have moved onto experimenting with new things (like medium-format on a Hasselblad).

However one thing I have kept quite consistent is using the same film (Kodak Portra 400) and getting to know the film speed really well via exposure. I always keep my aperture set at f/8 (during the day) and the ISO is consistent (always 400 on film), and the only variable I need to change/remember is the shutter speed. So over time, I have memorized my shutter speeds quite well. For example, if I’m shooting at f/8 with ISO 400, I will use these settings below:

- 1/1000th on a super sunny day

- 1/500th on a sunny day

- 1/250th during sunset

- 1/125th in open shade (that is pretty bright)

- 1/60th in open shade (that is pretty dark)

- 1/30th when the sun is setting

When it is nighttime (or I am shooting indoors) I will default to shooting wide-open (f/2) at 30th of a second. Also as a rule of thumb I always over-expose my film (it is better to over-expose because it is easier to bring back highlights in film, it is very hard to bring back shadows in film).

So try to simplify your variables. If you shoot with a rangefinder and a DSLR– you will find a hard time really mastering both at the same time. Try to focus on one camera system or lens before moving onto the next one. If you are shooting black and white, try to master it before moving onto color. If you like 35mm film, try to master that before moving onto medium-format. If you like 35mm as a focal length, try to master that before moving onto something wider like a 28mm.

34. Broaden your palette

Like I wrote in the prior section– you don’t want to just shoot with one camera and one lens for the rest of your life. There is a point when you want to experiment more and “broaden your palette” as Hido points out below:

“Sometimes now, I’ll use two or three cameras. I understand why one would want to use multiple cameras, have a broader palette. Every camera makes a different kind of picture. Every camera is like a different paintbrush. They record scenes in different ways.”

Hido is an artist and doesn’t want to limit his creativity or his vision. Therefore by using different mediums (35mm, medium-format, etc.) he creates a multi-faceted view of the reality he wants to convey:

“Using multiple cameras and formats has added new layers of richness to my work.”

Takeaway point:

So essentially once you have mastered a certain medium, a certain camera system, etc.– try to work towards “broadening your palette.”

Picasso didn’t just paint one style for his entire life, Andy Warhol experimented a lot with different printing processes, and Josef Koudelka evolved from shooting 35mm black-and-white film to shooting with a panoramic camera.

As a photographer you are also an artist. You want to show the world and reality in a certain way– and therefore use the right set of tools or paintbrushes to convey this reality.

35. On putting together photobooks

In this section, Hido shares a lot of useful advice on how to put together photo books.

To start off, he shares the importance of a photo book– of creating a permanent body of work, and the importance of having a structure:

“What I’m really talking about here is putting together pictures sequences that will be collected together into a book. The book can lead you to synthesize ideas and can become your permanent record of a body of work. When you pick up a book, you expect something from it. It has a structure: a beginning, a middle, an end. It’s an enclosed medium that you can come close to perfecting.”

Hido begins the book-making process by pairing individual photographs, and then onto making chains of images that create the structure of his project:

“A lot of times, I’ll just start by pairing individual photographs, keeping in mind that each image should become stronger out of coming together. And when you have a number of pairs, you start to pair the pairs. And then all of a sudden you have these chains of pictures that start to show the shape and structure of the story.”

Although Hido embraces digital technology, he believes the best way is to take the analog approach– to print out little pictures, put them on walls, or on the table. To him, the physicality of objects is important– and they also allow for randomness and serendipity to occur:

“I find it really helpful to work with pictures on paper, little printouts that you can move around on a table or on a wall. I’ve never found a fabulous pairing or a great sequence on a computer screen. For me, things start happening when I work with physical objects. I’ve accidentally sequenced some really great and surprising pairs of images because I had the ability to move paper around. The pictures scatter in a way that you can’t control or plan. You set a couple of photos down and realize they work together. As you start placing things together and they start to form chains you can move whole sections. It’s like making a paper movie.”

Another analogy that Todd shares is thinking of music. If you are listening to a good song, there is a certain tempo, rhythm, and cadence to the music that keeps you going along:

“When you’re putting together photographs for a book, it’s helpful to think of music. There may be motifs that appear and repeat themselves in different iterations in a long sequence. You can create a rhythm by being consistent from image to image and by paying attention to how the images hang together.“

However sometimes music is boring when it repeats itself. In those cases, it is sometimes good to mix it up– and surprise or shock the listener (or viewer):

“But once you’ve established a pattern, once the rhythm becomes familiar, break it. The viewer should be led along and then surprised. Just when the viewer knows what’s coming, do something different. When they’ve just seen a number of houses at night, introduce a landscape from the daytime. The reader will think, ‘Where’d this come from, and why is it so blurry?’ That picture is there specifically to keep the reader engaged, to be the wrong picture at the right time. In a way, it contaminates the rhythm and spoils the sequence, but in the right way.”

Takeaway point:

Think again about movies– some of the best movies are the ones which shock and surprise you in the middle of it. They call it a “plot-twist.”

Think of how you can add “plot-twists” to your own photography series. What images can you add to a certain sequence that will shock or surprise your viewer?

But up until that moment of shock– think about music and how you can have your subject go with the rhythm and the flow.

So strive for both: consistency in the flow of images and sequence, but also breaking the chain with something totally out of the blue – an image that doesn’t belong. Do this on purpose, and then show the sequence to a friend or another photographer in-person and judge their reactions via their facial expressions or when they pause on certain images. Be a great storyteller, with lots of shock and awe.

36. The importance of making objects

In this section, Todd Hido shares more about the importance of making physical objects (instead of purely digital).

I think this is a very important thing to note– especially as our world is becoming more and more digital. With digital cameras, we shoot digitally, upload them to the internet, but never see them printed out in “reality.”

Especially when you’re making a photography book– a digital photography book isn’t enough. The physicality of turning pages is an incredible experience– and something you need to do in the object-world (not just on a computer):

“Once you’ve made the paper movie, then you have to convert it into page-turning; there’s nothing like page-turning. When I’m working on a book, I have to have a dummy. Simulating one on a computer is not acceptable. You have to print it and hold it in your hands.”

So if you’re working on a book project, make several different dummies or maquettes. You can do it very simply– I know some photographers who make small 4×6 prints and just paste them into a notebook or a moleskine book. You can make cheap Xerox copies from your home printer, and put them together with glue or staples. Just make it physical– Todd explains more below:

“You’re making an object. Therefore, you have to bring it into the object world of paper and ink. Even if you make a rough dummy in black and white that is printed like crap and taped together with duct tape or whatever, you’ve got to be able to turn the pages.”

It doesn’t matter if you shoot in film or digital– you just need to make a physical object in photography. This physical object can be prints, a book, or an experience (like an exhibition):

“Making an object is crucial to photography. Everyone who is just shooting jpegs, they’re in trouble. They’ve got to learn how to make an object, whether it’s an image in a book or a print on the wall.”

Takeaway point:

Think of how you can make your photography more physical. If you have always shot digitally, perhaps you can try experimenting with film. Learn how to shoot film, load it into your camera, and process it by hand afterwards. Perhaps even take a darkroom-printing course, and learn how to make prints by hand (I learned this recently and it is an absolutely sublime and almost spiritual experience).

If you shoot digitally, perhaps all you need to do is just print more of your work. Print them at home, or send them to a lab to get them printed for you. Make small 4×6 prints when you’re editing or sequencing your work, or make larger prints to give away as presents. Frame your work. Print out your photos and make book dummies. Print out books via print-on-demand services like Blurb. Think of having an exhibition and put prints on a wall.

Try to think of how you can make your photography a more physical experience– and you will find more joy, novelty, and wonderment with your photography.

37. Take your time

With the digital age– we are focused and obsessed with speed. We feel like we need to shoot more, edit more quickly, and publish more work.

But remember– you can take your time. Don’t feel a rush to get your work out there. It is better to make fewer projects (and have them all be strong) than have a lot of work that is mediocre.

Todd Hido shares this same philosophy– he has been shooting for 25+ years and he only has a handful of projects he has worked on over the years. He explains more:

“One thing I often see with young photographers is this rush to get their work out there. I’m very ambitious, but I also know that it’s okay to wait until you’re really ready to show a body of work. People have these different tabs on their websites that show the portfolios of ten or fifteen projects. I don’t have ten projects, and I’m 25-years into this.”

Part of the pressure to share a lot of work is the fact that the internet has made sharing easy. But remember– take your time, and also remember to enjoy the process of making photographs. Slow down:

“Sharing your work with the public is easier and quicker than ever— but just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. Photographers also think that they need to have a book or a show right away. You don’t. When the time is right things will come together. In the meantime, try to enjoy making the pictures. Slow down and think about your craft.”

Takeaway point:

Don’t feel like you need to be in a rush with your photography. If you’re not a full-time photographer making a living from photography– why the rush? You’re not paying the bills with your personal photography projects. You are working on your photography because it is a passion and a love.

I personally don’t know anybody who makes a living from their street photography purely off of prints and book sales. So you don’t need to constantly pursue pumping out images to sell.

Slow down, and enjoy the process. I often find the process of making photos, editing them, and sequencing them more enjoyable than looking at the final and completed project.

Remember, the journey in photography is the reward.

38. Know what motivates you

We all have different motivations and reasons for why we make photographs. But often we don’t put these motivations and reasons onto paper. But by identifying what drives and moves us– we can stay inspired.

Todd Hido shares the difficulty of staying motivated and inspired in photography. We will constantly make excuses why we shouldn’t make photographs– and become dissatisfied and frustrated as a result:

“Once a book is printed and the show has come down, you have to stay motivated to go onto the next thing and make art for your own for the long haul. This is one of the biggest challenges for a working artist. There are all kinds of ways to get distracted. Like all of us, I’ve got stuff that I have to do most days that is not creative. You’re not allowed to use the business of living or your job as an excuse to not make photographs.”

Todd digs deep by sharing the importance of knowing what motivates us:

“Knowing what motivates you is key. Once you’re out of school, you’re on your own. There are no deadlines. No one’s expecting work from you each week. You’ve got to figure out some method, whatever it is, that keeps you on track to make artwork. For some people, taking a class or meeting with a group on a regular basis is motivation enough. Some of us just need someone to say, ‘Hey, I want to see what you’re doing.’”

Some of us are intrinsically motivated (driven from within) and some of us are extrinsically motivated (motivated by other people). One isn’t necessarily better than the other– they are just different. Know what drives you. If you are more extrinsically motivated, perhaps you need some sort of support group, photography club, or friend to keep you on-track in your photography.

Sometimes having expectations or schedules is a good way to stay motivated in your photography (or being in a class) as Todd explains through this story:

“My friend Paul takes this introductory screen printing class every semester at a local community college. He’s taken it so many times that they eventually told him he couldn’t sign up for it again. So now he signs up as Todd Hido, with my credit card— all so he can continue to take this class. The fact that every Wednesday he knows that he is supposed to go down there and screen print is what keeps him working.”

Takeaway point:

What ultimately drives you as a photographer? Is making photographs a way for you to escape the monotony of everyday life? Is making photographs a way to capture your reality and share it with the world? Is making photographs an excuse to meet others and socialize? Is photography a way for you to stay creative? Is photography a way for you to become recognized at something you are good at? Does shooting by yourself, or with other people motivate you? Do you need to stay in a photography class to keep moving forward? Do you ultimately want to publish or print your work in a book? Who is your intended audience? Yourself, or other people?

Ponder some of these questions to keep you motivated and inspired in your photography.

Conclusion

To sum up, I think there are so many valuable lessons that we can learn from Todd Hido in our photography. I have personally learned the importance of adding emotion, story telling, drama, and mystery into my images. I have learned how to better sequence images (thinking of films or music), how to better edit (less is more; all killer no filler), and the importance of taking my time (not needing to rush my work).

What you personally take from Todd Hido is up to you. And once again, even though he isn’t a street photographer– I think we as street photographers can learn a lot from his philosophies and way of working.

To learn more from Todd Hido and stay inspired, definitely pick up a copy of “Todd Hido on Landscapes, Interiors, and the Nude” and (if you can) copies of some of his books and projects. There are also excellent interviews with him online in which he shares his philosophies and working methods.

Follow Todd Hido

Books by Todd Hido

- Todd Hido on Landscapes, Interiors, and the Nude ~$21 USD

- Todd Hido: “Between the Two” ~$57 USD

- Todd Hido: “House Hunting”

- Todd Hido: Excerpts from Silver Meadows

- Todd Hido: Roaming Landscape Photographs

- Todd Hido: A Road Divided

Recommended reading/looking/listening from Todd Hido

Below are some recommended sources of inspiration from Todd Hido:

- Robert Adams: “Los Angeles Spring”

- Nobuyoshi Araki: “Femme de Mouche”

- Lewis Baltz: “Park City”

- Jean Baudrillard: “Cool Memories”

- Bernd and Hilla Becher: “Water Towers”

- Richard Billingham: “Ray’s a Laugh”

- Italo Calvino: “Difficult loves”

- Raymond Carver: “Short Cuts: Selected Stories”

- Larry Clark: “Teenage Lust”

- Walker Evans: “First and Last”

- Robert Frank: “Moving Out”

- Nan Goldin: “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency”

- Emmet Gowin: “Photographs”

- Craigie Horsfield: “Craigie Horsfield”

- Edward T. Linenthal: “Preserving Memory”

- Richard Prince: “Girlfriends”

- Sophie Ristelhueber: “Aftermath, Kuwait”

- Jo Spence and Patricia Holland: “Family Snaps: The Meaning of Domestic Photography”

- Larry Sultan: “Pictures from Home”