William Klein is one of my favorite street photographers of all time. I think one of the things that I love most about him is his “I don’t give a fuck” attitude about the way he approached street photography how he did things his own way. He rebelled against many of the contemporary styles of photography during his time, especially that of Henri Cartier-Bresson and other “classic” street photographers.

In this article, I will share what I have personally learned about street photography through his work. Also in the spirit of William Klein, I will use obscenities when illustrating some points. After all, I think that is what Klein would have liked.

1. Get close and personal

Klein experimented with lots of different focal lengths during his career– but he is most well-known for his up-and-close and personal work with a wide-angle lens.

This is what Klein said about his approach in his book: “William Klein: Close Up“:

“I photograph what i see in front of me, I move in close to see better and use a wide-angle lens to get as much as possible in the frame.

When I look at the work of William Klein, I feel that I am really there. I feel like an intimate participant of the scene, rather than a voyeur simply looking in. Not only that, but he is able to shove tons of content into the frame, so there are multiple subjects and point of interest–not just one single subject.

When Klein would photograph with a wide-angle lens, there would be considerable distortion in his images (which a lot of photographers don’t like). In an interview Klein shared why he preferred using a wide-angle lens (21mm-28mm) compared to something more standard like Henri Cartier-Bresson’s 50mm:

“Does it really bother you? In any case, I’m not deliberately distorting. I need the wide-angle to get a lot of things into the frame. Take the picture of may day in Moscow. With a 50mm jammed between the parade and the side-walk, I would have been able to frame only the old lady in the middle. But what I wanted was the whole group – the tartars, the Armenians, Ukranians, Russians, an image of empire surrounding one old lady on a sidewalk as a parade goes by.

In photography, I was interested in letting the machine loose, in taking risks, exploring the possibilities of film, paper, printing in different ways, playing with exposures, with composition and accidents. Its all part of what an image can be, which is anything. Good pictures, bad pictures—why not?

Takeaway point:

If you want to create a sense of intimacy in your photographs, don’t photograph half a block away with a telephoto lens. Rather, strap on a wide-angle lens (a 35mm or wider) and get up-and-close to the action. Become an active participant of the scene. Interact with the people, hear their conversations, and as a rule of thumb be close enough to see the colors of their eyes.

Also instead of just focusing on single-subjects, try to add more content into your frame. When using a wide-angle lens, I noticed that Klein did this best when photographing in a landscape format. This way he was able to add more subjects to his frame.

2. Keep a “photographic diary”

When Klein first started to photograph the streets of NYC in 1954, he did it with a care-free attitude. He wasn’t trained in photography at the time, but he simply captured what he found interesting. In “Close Up”, Klein Expands:

Before my book on New York, I was a painter. When I came back to the city in 1954, after six years away, I decided to keep a photographic diary of my return. These were practically my first ‘real’ photographs. I had neither training nor complexes. By necessity and by choice, I decided that anything would have to go. – William Klein (1990)

Sometimes when we shoot on the streets, we feel that we have to always work on a project or take our photography very seriously.

Although I do believe in working on projects and focusing when shooting on the streets, it is also important not to take things so seriously all the time.

Takeaway point:

By keeping a “photographic diary”– you can capture interesting moments of your everyday life through people on the streets. If you are feeling in a sad and depressive mood, you are probably more likely to spot that in the streets. So by photographing how you feel, you can create authentic and personal images.

Another takeaway point we can learn from Klein is the importance of the amateur approach. Being called an “amateur” is often a negative label. However the word “amateur” originated from the idea that someone did something for the love of it, rather than for the money, fame, or prestige.

So regardless of how much photographic training you have, just go out there and shoot. Don’t worry so much about the theory of photography, just shoot because you love it.

3. Go against the grain

When Klein was shooting in the streets in the 50’s, there were certain “taboos” when it came to photography. This included Grain, high-contrast, blur, decomposition, and accidents.

However Klein used these techniques to his advantage. His photographs weren’t clean, sterile, and clinical. Rather, they were full of energy, vibrance, and a sense of rebellion that went against the grain.

Of course now looking back we look at Klein as a visionary and a genius in his work and approach. However when he was photographing at the time, people either hated his work or didn’t understand how unique or original it was.

When talking about his pivotal New York Book, “Life is Good & Good For You in New York (1956)“, Klein had this to say:

“The resulting book went against the grain thirty years ago. My approach was not fashionable then nor is it it today.” – William Klein (1990)

In an interview with Klein (in his Aperture Monograph book), he shares how much American publishers abhorred his work:

“In the 1950s I couldn’t find an American publisher for my New York pictures,” he says. “Everyone I showed them to said, ‘Ech! This isn’t New York – too ugly , too seedy and too one-sided.’ They said ‘This isn’t photography, this is shit!’” – William Klein (1981)

Takeaway point:

I think what we can learn from Klein is the fact that he gave the middle-finger to everyone else when it came to his photography. He did things his way, and certainly went against the grain. He knew that his photography wasn’t fashionable, but he didn’t give a flying shit.

Even when he talked about his work in his book: “William Klein: Close Up” in 1990, he still mentioned how his work still wasn’t fashionable.

4. Pursue ethnography

According to Wikipedia, “ethnography” is defined as the following:

Ethnography (from Greek ethnos = folk/people and grapho = to write) is a qualitative research design aimed at exploring cultural phenomena. The resulting field study or a case report reflects the knowledge and the system of meanings in the lives of a cultural group. An ethnography is a means to represent graphically and in writing, the culture of a people.

Why do I bring up ethnography in terms of Klein’s street photography? Well, he mentioned it himself when describing the content he pursued for his “Life is Good & Good For You in New York” book:

As for content: pseudo-ethnography, parody, dada. I was a make-believe ethnograph in search of the straightest of straight documents, the rawest snapshot, the zero degree of photography. I would document the proud New Yorkers in the same way a museum expedition would document Kikuyus. – William Klein (1990)

Although Klein refers to his work as more of a “pseudo-ethnography” (or wanna-be ethnography) his work certainly explores the culture of people in New York.

What did Klein find in the people of New York in the 50’s? Well according this his words he found: “…black humor, absurd, panic.”

His photographs certainly aren’t of the more romantic photographs like that of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Rather, his New York photographs are quite grimy, rugged, and raw. They show a side of New York that many Americans found repugnant. He photographed in the rough parts of town, documented the manipulation of the media, as well as the grittiness of the streets.

Takeaway point:

When you are pursuing your own photography, don’t try to just make interesting images. Rather, try to pursue the “sense of place” of wherever you are photographing. Through ethnography, try to pursue to “…represent graphically and in writing, the culture of a people.”

5. Be purposeful when you are out shooting

When Klein first started photographing the streets of New York in the 50’s, he did so with a “photographic diary” approach. At the time, he didn’t think of creating a book on New York or anything of the sort.

However one thing that I found fascinating is how he mentions that he doesn’t believe in the idea of “carrying a camera everywhere you go.” Rather, he mentions how he photographs with high-intensity when working on a project or a book:

“I don’t roam around with a camera and never did. I took pictures in spurts, for my books, for some assignments or on special occasions. Like people who take out their cameras for Christmas and birthdays. Each time, like them, probably, I feel it’s the first time and as if I would have to relearn the moves. Luckily, it comes pretty fast, like riding a bike.” – William Klein (1990)

Interesting enough, Klein didn’t actually spend a lot of time of his life shooting on the streets. However because he focused intensely, he was able to finish his books and projects quickly and efficiently.

John Heilpern wrote this about William Klein in an Aperture Monograph of him (1981):

“Just as Klein himself lives in self-inflicted limbo in paris, he appears to have made of his career what amounted to a willfull noncareer. Everything he worked at over the years, from his paintings to his later political films, he abandoned eventually to start afresh.

His four books of photography, on which so much of his reputation is based, took him an average of 3 months each to photograph and several more months to edit and design. (Klein did the design, typography, covers, and texts for all his books.) But little more than four years of his life have actually been spent seriously taking photographs.”

Takeaway point

I still think it is a good practice to carry a camera with you everywhere you go, as many “decisive moments” tend to happen at the most random of times. I always carry a compact camera with me, and have found some of my best photographs in the least likely places (supermarket, waiting in line at airport, while running errands).

However I still think there is great value in Klein’s methodology in working in short and focused bursts.

It still blows me away how Klein was able to photograph most of his photography books of New York, Rome, Paris, and Moscow on an average of only 3 months. Most photographers take years or even decades to finish photographing for their books.

I suspect it is because when Klein was shooting on the streets, he didn’t dick around. He hit the streets with passion and fervor, and shot in the streets without hesitation. Through his purposeful shooting on the streets he was able to create powerful and memorable photographs.

So even if you don’t have a lot of free time to shoot on the streets, don’t fret. If we can learn anything from Klein, it is that it is quality, not the quantity of time we use when shooting in the streets that matters.

6. Have fun

The reason I like to shoot street photography is because it is fun. When I am out on the streets, I feel like a kid again. Street photography gives me the opportunity to explore, interact with people, and lose myself in the moment while photographing.

What was the main impetus which drove Klein to first start taking photographs? Klein mentions the sense of fun and enjoyment that he got shooting on the streets:

“I was taking pictures for myself. I felt free. Photography was a lot of fun for me. First of all I’d get really excited waiting to see if the pictures would come out the next day. I didn’t really know anything about photography, but I loved the camera.

Klein also shares the excitement that he got when experimenting shooting on the streets:

“… a photographer can love his camera and what it can do in the same way that a painter can love his brush and paints, love the feel of it and the excitement.

I would look at my contact sheets and my heart would be beating, you know. To see if I’d caught what I wanted. Sometimes, I’d take shots without aiming, just to see what happened. I’d rush into crowds – bang! Bang! I liked the idea of luck and taking a chance, other times I’d frame a composition I saw and plant myself somewhere, longing for some accident to happen.

Choosing location, maybe a symbolic spot, the light and perspective – and suddenly you know the moment is yours. It must be close to what a fighter feels after jabbing and circling and getting hit, when suddenly theres an opening, and bang! Right on the button. It’s a fantastic feeling.”

Takeaway point:

Don’t forget to have fun when shooting on the streets. If there is ever a point in when shooting in the streets is no longer fun for you, you should probably stop and pursue some other type of approach.

For example, for about 5-6 years I enjoyed shooting street photography in black and white. However after a while, it didn’t interest me as much and didn’t feel as challenging. However now that I have switched to shooting my street photography exclusively in color film, it has opened up new opportunities and challenges which I find fun.

Let your own interests lead your street photography. Don’t really care what types of projects other photographers may be pursuing. After all, what is interesting (and fun) to them may not be interesting or fun to you.

7. Interact with your subjects

Street photography is generally understood as capturing candid moments of everyday life. However the paradox is that some of the most memorable street photographs taken in history were either posed or as a result of the interaction with the photographer.

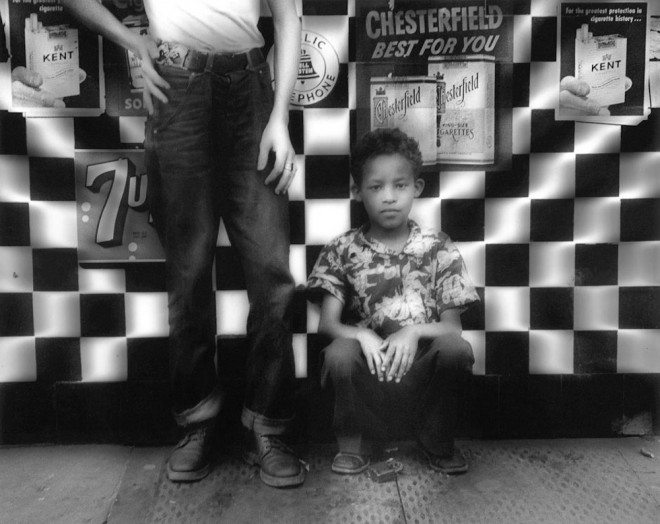

Think of Klein’s famous “Kid with gun” photograph. Although the moment looks raw and candid, the photograph was actually a result of what Klein said to the kid. When Klein saw the kid with the gun, he told him: “Look tough.” The kid then turned toward Klein, and pointed his gun straight at him– giving an incredibly brutal look.

If you look at Klein’s contact sheet of the shot, you can see the next photograph the kid is smiling and posing with one of his friends.

So how did Klein interact with his subjects when shooting on the streets? He explains how his subjects were aware they were being photographed, but not always 100% sure:

“Yes, but they didn’t know I might be photographing a hundred other things going on behind them—someone lurking in the background, a shadow, a reflection, posters, traffic, junk. [I’d say], ‘Hold it! Don’t move! Hey, look this way!’ People would say, ‘What’s this for?” I’d say, ‘The News.’ ‘The News! Wow! No shit!’ I didn’t much care.”

So doesn’t this mean that Klein was simply manipulating his subjects? This is an interview question that was given to him, in which Klein responds:

“Not always. We’re not completely brut, you know. I thought people could be provoked to pose or play a role in some situations. Why not? People have posed for portraits for centuries. When I was a kid in New York, if some tough kid caught you looking at him he’d say, ‘Hey! What are you looking at?’ If you said, ‘I’m looking at you,’ he’d say, ‘Oh, yeah!’ if you said, ‘I’m not looking at you,’ He’d say, ‘why not?’ either way you were in trouble.”

Klein also shares his thoughts on how pointing a camera at someone you don’t know can cause a tension, but how it is also generally accepted:

“In rough neighborhoods in New York [sometimes]… it’s better not to look. So if you point a camera at a stranger, you’re almost breaking a tradition of not getting involved. Yet in a way, the camera erases involvement. Its accepted.”

Klein knows how photographing someone can cause someone to be provoked, but in the end– most people quite liked being photographed:

“In another way, it could be worse—a provocation and a threat. But generally, the people I photographed in New York seemed flattered. If I manipulated them sometimes, they didn’t seem to think they should mind. Elsewhere, if I’d get people to clown around with me, like people in Italy to pose in hierarchical Roman way, I think that should be a valid picture. They’re telling us something about themselves.”

But if a photographer provokes a person, what does it show except the result of the provocation? Klein thinks that people’s reactions show less of the photographer, but more of the subject him/herself:

“Rather than catching people unaware, they show the face they want to show. Unposed, caught unaware, they might reveal ambiguous expressions, brows creased in vague internal contemplation, illegible, perhaps meaningless. Why not allow the subject the possibility of revealing his attitude toward life, his neighbor, even the photographer? Both ways are valid to me.”

Klein shares how sometimes people he provoked did things he couldn’t have even imagined:

“In any case, very often people did things I couldn’t have organized or imagined. A mother points a toy gun at her child’s temple. Maybe I asked her to do it, I honestly forget. But lets say I did, out of some perverse inspiration. At the same time, though, she holds the child’s hand in the most tender, touching way.

The way a subject reacts to the camera can create a kind of happening. Why pretend the camera isn’t there? Why not use it? Maybe people will reveal themselves as violent or tender, crazed or beautiful. But in some way, they reveal who they are. They’ll have taken a self-portrait.”

Takeaway point

I know a lot of street photographers who are vehemently opposed to the idea of interacting with your subjects. However I don’t think it is a problem to interact with your subjects when shooting on the streets.

I often interact with my subjects when I’m shooting street photography. I might sometimes first chat with them, get to know more about them, and ask to take a few photos of them. In other cases, I will ask them to pose for me a certain way I’d like to (asking someone to take a puff out of their cigarette, look straight into the lens, or not to smile).

Other times I have taken Klein’s line of saying: “look tough” to some people I meet on the street. The type of expression or look they give me is generally much more interesting than anything that I could have orchestrated myself.

Don’t feel that all the photographs you take have to be 100% candid. I often feel that the photographs in which people interact with their subjects are more interesting than candid moments. I think Klein would agree with this sentiment whole-heartedly.

8. Don’t worry about cameras

As photographers we can be a bunch of nerds. We spend a lot of time on gear forums and obsess over the sharpness, bokeh, or “characteristics” of certain lenses. We spend a lot of time talking about the “ideal camera” for street photography. The problem is that after all this equipment masturbation, it can take us away from actually going out and taking photographs.

What did Klein feel about talking about gear and equipment? He wasn’t very interested in it he was more interested in shooting:

“The right filter, the right film, the right exposure – none of that interested me very much. I had only one camera to start with. Secondhand two lenses no filter, none of that. What interested me was getting something on film to put into an enlarger, maybe to get another picture. And I was in a big hurry. Once I got used to everything in New York I knew the trance would wear off. So I took pictures with a vengeance.”

Takeaway point:

I used to be totally obsessed with gear. When I was an undergraduate student at UCLA, I worked in IT as my work-study job and spent far too much time on gear forums. I would be like the thousands of other members discussing inane matters like the corner-sharpness of Canon-zoom L lenses vs Canon prime lenses. I spent too much time studying “bokeh characteristics” of different lenses. I spent too much time looking at 100% crops of high-ISO samples of different cameras.

What was the result of all that? Well first of all, it made me depressed as hell because I could never afford all of those expensive cameras and lenses (especially as a student). In-fact, it discouraged me from going out and actually taking photographs –as I felt that my gear was inadequate in creating good images.

However over the years, I have found how little gear has to do with creating memorable images. To think that Henri Cartier-Bresson made some of his masterpiece images in the early 1920’s with a primitive Leica and ISO 25 film! But yet nowadays we bitch and moan about our cameras not being able to go above ISO 1600.

At the end of the day, we should follow Klein’s advice and don’t worry so much about the camera or technical settings. The most important thing is going out and producing images.

9. Don’t worry about technical settings

Many photographers I know tend to obsess over the technical settings. They need to have the “ideal” lens for a certain situation, to use the “ideal” f-stop, to use an “ideal” shutter speed, and the “ideal composition.”

Klein gave the middle finger to all of that. He was the master of experimentation and trying everything unconventional–especially when it came to the technical details. Klein shares:

“I have always loved the amateur side of photography, automatic photographs, accidental photographs with uncentered compositions, heads cut off, whatever.”

Klein would also experiment with playing with grain, contrast, blur, and manipulating negatives. This is what he had to say about his New York book:

“The New York book was a visual diary and it was also kind of personal newspaper. I wanted it to look like the news. I didn’t relate to European photography. It was too poetic and anecdotal for me… the kinetic quality of new york, the kids, dirt, madness—I tried to find a photographic style that would come close to it. So I would be grainy and contrasted and black. Id crop, blur, play with the negatives. I didn’t see clean technique being right for New York. I could imagine my pictures lying in the gutter like the New York Daily News.”

In one of his most famous images of a kid in front of a checkerboard tile wall, he jiggled the enlarge head slightly up and down to give the impression that the photograph was rushing at the viewer. Certainly a technique that wasn’t conventional at the time.

Klein would often shoot with slow shutter speeds to create motion and blur in his photographs. This was also against the grain at the time, in which sharp and in-focus photographs were the standard. When asked about why he used blur in his photographs, Klein responded:

“If you look carefully at life, you see blur. shake your hand. Blur is a part of life.”

Klein wasn’t a technical photographer when he started, and he never tried to. He actually would try to purposefully make “mistakes” in his photographs from a technical standpoint:

“I have always done the opposite of what I was trained to do… having little technical background, I become a photographer. Adopting a machine, I do my utmost to make it malfunction. For me, to make a photograph was to make an anti-photograph.”

Takeaway point:

Don’t feel that your photographs have to be technically perfect. Experiment with different approaches in terms of both how you photograph, who you photograph, and how you post-process your images.

Personally I don’t like photographs that are “over-processed” like HDR photographs. However what Klein was doing with his photographs (extreme contrast, grain, and negative-manipulation) in the past is probably the modern-day equivalent approach of HDR.

So once again, screw the rules and create your own new ones. That is how Klein made a name for himself perhaps that is how you can make a name for yourself too.

10. Be opinionated

We as street photographers aren’t documentary or reportage photographers. We are not trying to create images that attempt to show an “objective” view of reality. Rather, the images we create are generally for ourselves–portraying our own view of reality.

I think what makes a photographers’ work interesting is how he/she sees the world. I think that photographers should have an opinion about the society around him/herself and show it through his/her photographs. I think that striving to search for “objectivity” will simply make one’s work boring and not very interesting.

Klein’s street photography was very subjective. He traveled to places all around the world and photographed things how he saw them. He shares how he approached street photography in New York:

“In New York I took responsibility for the people I photographed. I felt I knew them – the people, the way they relate to each other, the streets, the buildings, the city. And I tried to make sense of it all. I just photographed what I saw though its true I used the camera as a weapon in New York.

When Klein visited Tokyo, he approached street photography there much differently:

“In Tokyo [the camera] was more of a mask, a disguise. I had only the vaguest clue to what was going on. I wasn’t there to judge anything. I was an outsider and felt pretty uncomfortable sometimes. Have you ever eaten an official Japanese dinner for four hours on your knees? It was different in New York.”

Klein also explains how he believed in getting personally involved in his photography:

“In a way its true I had a lot of old scores to settle. I was involved. According to the Henri Cartier-Bresson scriptures, you’re not to intrude or editorialize, but I don’t see how that’s possible or why it should be. I loved and hated New York. Why shut up about it?”

With Cartier-Bresson being almost like a demigod in the photography world, he set most of the standards for photographers. But Klein stayed true to himself and rebelled. This is what he had to say about HCB:

“I liked Cartier-Bresson’s pictures, but I didn’t like his set of rules. So I reversed them. I thought his view that photography must be objective was nonsense. Because the photographer who pretends he’s wiping all the slates clean in the name of objectivity doesn’t exist.”

Klein also makes the great point on how photographers are subjective when photographing a scene:

“How can photography be noncommittal? Cartier-Bresson chooses the photograph this subject instead of that, he blows up another shot of the subject, and he chooses another one for publication. He’s making a statement. He’s making decisions and choices every second. I thought, if you’re doing that, make it show.”

Klein talks more about how photographers are prejudiced, and how the camera adds to that prejudice:

“Id say that such a person wouldn’t let the camera express itself. He’s prejudiced. A camera can record the passage of time, if only for a fraction of a second. Why say it shouldn’t? Besides, if you look carefully at life, you see blur. Shake your hand blur is a part of life. But why must a photograph be a mirror?

Most things I did with photography are considered acceptable today – except maybe this use of a wide-angle. It seemed more normal to me than the 50mm lens. You could even say the 50mm is an imposition of a limited point of view. But neither lens is really normal or correct. Because in life we see out of two eyes, whereas the camera has only one. So whatever lens is used, all photographs are deformations of what you actually see with your eyes.”

Takeaway point:

Klein was very outspoken and opinionated when it came to his personality and especially his street photography. He believed that photographers should show their opinions of the world. Klein believed photographs should be subjective, and couldn’t be objective (even if the photographer tried).

After all, the photographer makes the conscious choice of what to photograph and what not to photograph, whether to capture a scene in black and white or color, or use a telephoto or wide-angle lens. All of these show subjective views of reality.

I believe in what Klein says as well. As street photographers, we aren’t covering a news in a war. Our photographs aren’t nearly as political as that of photojournalists or reportage photographers. Therefore we should embrace the fact that one of the beauties that lie in street photography is that it is generally for ourself, not for others. We don’t need to show an “objective” view of reality. We need to editorialize life and make it more subjective, personal, and intimate.

Conclusion

Klein was one of the most rebellious street photographers in the course of history. He went against all of the traditions of photography– such as composition, using wide-angle lenses, blurring his photographs, getting up-close-and-personal, interacting with his subjects, creating grainy and high-contrasty images, and far more.

I still feel that Klein is one of the most underrated street photographers, as he is not as well-known as some of the more prominent street photographers in history (many photographers who know Henri Cartier-Bresson have no who idea who Klein is).

There is still a lot I have to learn about Klein, but the things I mentioned above is what I have personally learned from him. Give the middle-finger to convention and fuck what other people think. Go out, have fun, and pursue the type of street photography you enjoy. If people tell you what you are doing isn’t “street photography” just ignore them and do what you love the most, photograph.

Videos on William Klein

The Many Lives of William Klein (2012)

A superb documentary on William Klein, which tells more about his history and shows his spunky personality:

William Klein: In Pictures by Tate (2012)

An interview with William Klein and a behind-the-scenes glimpse into his Paris studio:

William Klein: Contact Sheets

A look behind the stories behind some of William Klein’s most famous images — narrated by Klein himself:

Books by William Klein

William Klein: Life is Good & Good for You in New York

William Klein’s first and most influential book on New York City. A must-buy. Not only that, but very affordable (as it is a reprint of the original book).

William Klein: Rome

Superb photographs by Klein shot in Rome. Good news: it is still in print and available on Amazon.

William Klein: Paris + Klein

A lovely book of fascinating crowds in Paris. Shows a lot of his work in both black and white in color, and also with a flash.

William Klein: Tokyo

Unfortunately sold out most everywhere, or extremely expensive:

Klein: Moscow

Unfortunately sold out most everywhere, or extremely expensive:

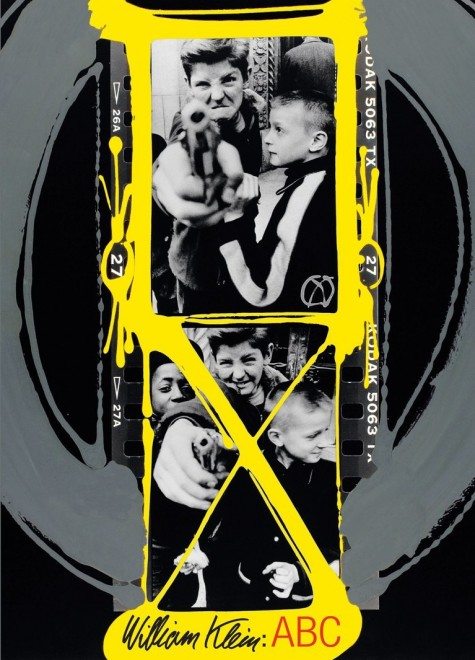

William Klein: ABC (2012)

A new comprehensive book published on Klein. If you want to learn more about the work of Klein, this book has it all. It includes New York, Moscow, Rome, Tokyo, Paris, his fashion photography, and painted contact sheets. A great introduction, and very affordable (~25 USD)