(“Nails” from my City of Angels series)

Editing in street photography is one of the most important aspects to know. When I refer to “editing“, I am referring to the act of choosing your best images, rather than “post-processing”. However nowadays when most photographers refer to “editing” their work, you can almost determine with 99% accuracy that they mean “post-processing” their work. Due to this confusion and interchanging use of the word “editing” – the true art of editing of choosing your best work is a lost cause.

For this article, I will attempt to explain why editing is so important in street photography and give practical tips and advice on how you can become a better editor of your work (and how to ask others for advice as well). Keep reading if you want to find out more!

Introduction

Nowadays everyone is a photographer. You see cameras everywhere. On our mobile phones, on our tablets, on our DSLR’s, point-and-shoots, micro 4/3rds, rangefinders, and so on. This means that we have seen a huge proliferation of images on the internet, more than ever. I recently read something on the internet that said something along the lines of, “Within the last year, more people have taken and uploaded images than the last 10 years combined” (don’t have the citation for this). Regardless if this statistic is true or not, the point is that now on the internet, there is a massive over-saturation of images online.

I strongly believe in the maxim, “Less is more“. I try to apply this to my own personal life, and have found it holds strong to street photography as well. It is commonly said that, “You are only as strong as your weakest photograph” – which means that your portfolio better be bullet-proof and only include your strongest images. However the problem that many of us street photographers face (myself included) is that we are horrible editors of our own work, and often show lots of weak images online.

How to edit your own work

Editing your own work is incredibly difficult, and it comes with time, practice, and patience. Here are some things I have learned along the way which have helped me personally become a better editor of my own work- advice that I have learned from myself and from others.

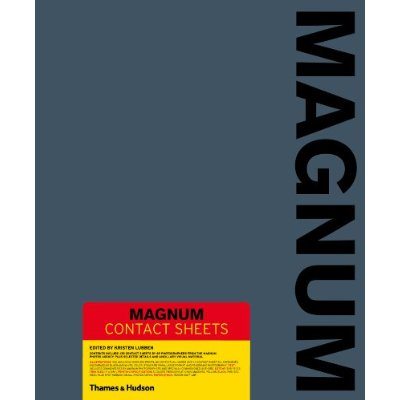

1. Read tons of photo books

You are what you eat. If you only look at mediocre photographs, you can only aspire to take mediocre photographs at best. If you look at great street photographs, you will start to get a better understanding of what makes a great street photograph – and aspire to take great photographs.

By comparing your own work to the work done by the greats, you will become far more critical of your own work when editing.

I have written posts addressing this titled, “Buy Books, Not Gear” and have a list of “75 Inspirational Street Photography Books You Gotta Own“.

2. Limit the amount of photos you upload

![[Street 2010-2011] #33](https://i0.wp.com/farm7.staticflickr.com/6221/6347458926_9f4d460a9f_z.jpg?resize=640%2C425)

a) Cause you less stress on the pressure of having to constantly produce and upload

b) Cause you to only show your best work

Remember, “less is more”. By showing less of your work, the quality of your photographs will be far more better in general- which will help curators better judge your work. Personally I am always on the lookout for great street photographers to feature on my blog, and spend quite a bit of time cruising Flickr. I’m quite busy, so I generally will look at only the first 5 or so photographs from a photographer. If all of those 5 shots aren’t absolutely stellar, I generally move on.

I used to fall victim to the trap of having to upload a photograph everyday. I noticed as a result the overall quality of my stream on Flickr started to go down, but I always felt so pressured to constantly upload. Projects like the “365 project” is good in theory (it helps you shoot much more) but I would suggest something a bit modified– shoot everyday (365/days/year) but upload only once a week.

3. Wait a certain period of time before you upload

I liken editing your work like letting a steak marinade. If you want all the juices to soak in, and truly appreciate something- you gotta give it some time and not rush it. The same thing goes with a nice wine- you gotta uncork it, and let it “breathe” to truly unlock the true aromas and tastes.

Apply the same concept to your own street photography when it comes to editing. I currently am on a challenge from Charlie Kirk in which I am not uploading any of my photographs online for a year- and showing my best 20 at the end of the year. A year is a bit extreme, but I have to say- it has taught me a great deal about patience and is helping me become a more crucial editor of my own work.

If I could give some advice, I would say wait at least at week before uploading any of your photographs online. If anything, I would prefer waiting at least a month before uploading any of your work. Try to distance yourself as far away from your own work as you can – until the point that you forget about the photographs that you have took. This can therefore detach any sort of emotional attachment you have for your own photographs.

One of my favorite quotes is by Garry Winogrand that addresses this: “Photographers mistake the emotion they feel while taking the photo as a judgment that the photograph is good”. Winogrand would often wait for at least a year himself before processing any of his photographs as well- so he could distance himself as far away from his own work as possible.

If you find yourself incredibly impatient (like myself) I suggest shooting film. Film will help you slow down, not look at your images so instantly, and typically wait for a long time before seeing any of your images.

4. Consider whether or not you would like to show that image in an exhibition/museum

One of the tips I have gotten from other photographers is to ask yourself when editing your images: “Would I consider this photo to be worthy of a gallery or a museum?” If the answer is no, you should probably ditch the image.

5. Think about the meaning of the photograph

I think that in street photography, people are obsessed too much with “pretty” street photographs- often involving lots of bokeh or even making their photos HDR. Aesthetics are important to making a great street photograph, but they are only used to highlight what I consider to be the most important thing in a street photograph – the meaning.

A great street photograph needs to have soul and meaning. Consider what you are trying to say through a photograph – and if it resonates with you. Does the photograph have a statement about society? Does it have a statement about individuals or humanity? Does it make you think about the world in a different way?

6. Consider the composition

Another Winogrand quote I love very much is, “Every photograph is a battle of form versus content.” I interpret this quote as meaning that form is the composition, framing, and technical details of a photograph while content is the meaning of the photograph (see previous point 5).

Composition is very important in street photography as it highlights to the viewer what they should be looking at (through suggestions of leading lines, symmetry, and arrows) while also creating balance and harmony in the image which makes it pleasing to look at.

I am not an expert when it comes to composition, but the bets way to learn composition is to study a lot of work by Henri Cartier-Bresson or check out Adam Marelli’s blog. One of his recent series of posts talking about HCB titled “The Surrealist Manifesto” is incredibly insightful.

7. Is the photograph a cliche?

A cliche is a photograph that has already been done before, and by doing it again makes it “gimmicky”. The tricky thing when it comes to cliches is that I think they often work well- because they connect with a large audience of viewers. These usually involve people kissing, posters interacting with people, or dogs in cars.

If you happen to take a photograph that looks like another photograph – don’t immediately ditch it. However if you find yourself thinking that the photograph you took is far too similar to a famous photograph you have already seen and doesn’t offer anything new- you perhaps might want to ditch it.

For further reading on cliches, this blog post by Martin Parr on “Photographic Cliches” is quite interesting.

8. Does it fit into a series?

When you are editing down your street photography, consider if it will work in a series of your own work. For example, if you are shooting almost entirely black and white and then you suddenly have a color photograph- you might not want to show that one single color photograph against 30 other black and white images. Similarly, if you usually shoot street portraits of people- you might not want to include a random photograph of a bird flying in the air- as it will break the flow of your portfolio or series.

My suggestion is not to get rid of the image – but simply not show it. Rather, hold onto it and once you have a set or a series of around 10-15 images, show it then.

9. Look for the failing aspects

Street photography is incredibly hard. It is very rare that you take a great photograph. In an interview with Martin Parr, he reported taking tens of thousands of photographs a year, but only making a good image a year.

When you look at your own photographs, don’t make excuses on why certain things are distracting. Rather, realize that it can destroy your shot. You can have the most incredible street photograph ever taken, but even something like a distracting car or lamppost can ruin the photograph.

As Winogrand said, “The good [photos] are on the border of failure.”

10. Does it reflect who you are?

When editing your work, consider if they are a reflection of you as a person. Don’t try to force certain images. For example, if you find yourself to be a quite happy-go-lucky person, showing incredibly dark photographs may not be a good idea. If you consider yourself a dark person, you probably wouldn’t want funny photographs in your portfolio (unless you are going for that on purpose).

Of course when we are out shooting, inevitably what we shoot is a reflection of who we are – as we only take photographs of things we are interested in. However still consider that when others look at your work, they will judge and consider who you are. Therefore choose your photographs wisely when editing.

How to have others edit your work

I was recently in London and judged for the London Festival of Photography 2012. Something that really struck me is a quote from Mike Seaborne, a photographer and former curator for the Museum of London. He said, “Photographer should never edit their own work” and illustrated an example of how a photographer he once exhibited oversaw a phenomenal shot. Mike only saw the “hidden gem” of a shot while looking through the photographer’s contact sheets. After discovering that one image, it was used as a lead image in posters, magazines, and advertisements and was very well-received.

However getting others to edit your work is often a conundrum- as what photos appeal to them may not always appeal to you. Also the selection of images they choose is often a different interpretation than what you have intended.

Regardless, I believe always getting a second pair of eyes on your work is important- as others can help find the inconsistencies and weaknesses in your images. Here is some advice I would give when having others edit your work:

1. Have an in-person critique

In-person critiques will always trump online critiques- as the critiques you will get are often more thoughtful, longer, and you can see subtle details like how people react to your images- and what images catch their eye.

2. Ask them to be brutal

A good critique should be honest and brutal. Sugar-coating a critique may be “nicer” to the photographer getting judged, but will not be as helpful to get constructive criticism that can help them become a better photographer. A strong critique doesn’t necessarily have to be mean, but once again – brutal honesty is of crucial importance.

3. Ask people that you respect (and who are better photographers)

When you ask for critique- be conscious on who you are getting it from. The critique from a macro flower photographer of course won’t be as helpful as a critique from a well-respected street photographer.

Whenever I ask for critique of my work, I ask other street photographers whose work I respect. Some photographers I had critique my work recently include Charlie Kirk, Dirty Harrry, David Gibson, and Matt Stuart.

4. Ask them why certain shots work and others don’t

As important as it is to get constructive criticisim on why certain shots don’t work- it is also equally important to understand which of your shots do work well. At times people critiquing your work will say that either a shot “works” or “doesn’t work”. However make sure to ask people why a certain shot works and doesn’t work- so it can help you understand your own images even more.

5. Ask online critique groups

It is difficult to find online street photography critique groups that are helpful. However two which are great on Flickr include “Street Smarts” and “Street Crits“. Both of the groups are quite ingenious because you need to give constructive criticism to get it back. Therefore this creates a positive feedback loop in which everyone is helped out! Also check out the “Image Critique Thread” on HCSP.

Conclusion

Editing is quite possibly the most difficult things in street photography. I feel the act of of shooting street photography is quite easy, but boiling down to your best images is incredibly difficult. It is almost like choosing from your children- and deciding which of your children to get rid of.

The best way is to keep yourself emotionally detached, and let your images sit and marinade (like a nice steak or wine), and always ask for a second opinion. And remember at the end of the day, “less is more” and shoot to please yourself and not others!

For further reading regarding editing in street photography, check out this thoughtful post by Nick Turpin titled, “Edit edit edit” and another post (in response) by Blake Andrews titled, “Streetwise“. You can also check out this interesting discussion about editing on HCSP.

What advice do you have for street photographers when it comes to editing? Share your thoughts and advice in the comments below!