I am very excited to share the newest documentary film by Cindy, titled: “Velcro Shoes”. The film is based on an essay she wrote “The Slow Undoing of Velcro Shoes“.

Why I consider her film so great:

Podcast

Iterative process

First of all, I find it hugely fascinating — for her to have taken a poem she initially wrote, and transforming it into a film.

“Up-cycling” of older documentary footage

I love looking at and watching old documentary footage. What greater joy than to experience old footage, but told through a new lens by (modern) Cindy?

The footage is of Cindy at age 2 (1990), and now Cindy narrating at age 32 (2020). 30 year gap; isn’t the fact that this footage still lives on amazing???

Your story and family story is important

When I watch documentaries, I prefer to watch extended narratives focusing on one person, one family. Of course we cannot extrapolate one individuals’ experience to all people, but this is what history is all about … story-telling! History and story is the same word; remember that! No such thing as ‘objective’ history. History is a masterful story told by artists — who decide what to pick and choose, and what to omit.

Lesson:

Tell your own story.

ERIC KIM

Description by CINDY

A film on loss and language

Directed, Produced, Edited, Words by Cindy Nguyen

Based on the Original Essay “The Slow Undoing of Velcro Shoes” by Cindy Nguyen, Visuals by Jimmy Tran, and home video footage made by my uncles in 1990 Little Saigon, Southern California.

Director’s Statement

“VELCRO SHOES” film is part of “Mẹ [Mom], Translated ,” a project on intergenerational language and love. VELCRO SHOES navigates the interwoven journey of loss and language for multilingual, third culture kids like myself. My maternal language of Vietnamese is defined by my family’s refugee resettlement in 1990’s southern California Little Saigon. Yet over time my language of expression also experienced a process of displacement. Rather than simply moving from Vietnamese to English, my language embodied our family’s living history and affective articulation of 1990s Vietnamerica.

Due to the current COVID-19 situation, my family and I have been physically separated across the East and West Coast. I initially wrote a version of this essay while living and working in Vietnam and Jimmy Tran made accompanying visuals here. In the longer essay, I reflect on how my ‘Vietnamese language’ is deeply tied to the textures of my specific family history as Catholic refugees, relocated to southern California, and coming of age in the 90’s. The initial essay meditates on the feeling of loss of maternal language and nostalgic yearning for the comforts of family, love, and acceptance.

In this film, I sought to depict how language and memories transform in ways that heal and nurture the soul in difficult times. This is the only video footage we have of our childhood because my uncles made these home videos to send to our family still in Vietnam who were not able to leave. Through making this film, I transcend the physical and temporal distance between me and my family. I remember and embrace the brighter loving moments. I hope for the time when we as a family can be reunited again.

On Velcro: Love, Language, Loss

As a kid, I was mesmerized by velcro. Velcro made life so much easier than buttons, zippers, and hooks. It made a relentless yet familiar scratching sound each time I undid it to kick off my shoes, opened bags, ripped off my jacket (those same pesky jackets that adults seem to keep bundling me up in, out fear that I would get sick from this foreign and cold American climate of Southern California).

Velcro was secure, predictable, safe. On the other hand, moving on from velcro is part and parcel of growing up, a transition to the fashion items of adulthood–refined maturity, quiet elegance, and the unnecessarily complicated world of laces.

I yearned for the simplicity and security of velcro. Yet I also feared what came afterwards. Growing up is an intertwined rope of ‘reaching for’ and ‘hesitancy of’ the familiar and the beyond. I sought to convey a childhood of wonderment and possibility in VELCRO SHOES. Yet, for me, reaching for that world beyond also meant confronting a certain sense of loss. I ‘lose’ my maternal language and the familiar world of home. I ‘lose’ a certain time and place of playful surrender without fear of judgment. By making this film as an adult, I imbue new meaning to language and loss that is textured by bittersweet love and gratitude.

Please share this film VELCRO SHOES and the project “Mẹ [Mom], Translated ,” with anyone who

- has felt misunderstood

- dances freely or uneasily between categories and languages

- has used google translate with their parents and family

- has been told “you are not really ____”

- does not know where or who ‘home’ is

- wanders and wonders why

Artists, bilinguists, academics, Asian Americans, Vietnamese, everyone…I would really appreciate your feedback on this piece and the project. Please share your thoughts, feelings, feedback with me at misreadingart@gmail.com

Follow the project “Mẹ, Translated” and film/soundscapes on Youtube.

GIF

Screen

Audio

FILM

The Slow Undoing of Velcro Shoes

My mom speaks a particular linguistic formula of Vietnamese.

My mom speaks a particular linguistic formula of Vietnamese.

Take two generations of refugees,

Multiply it by memory, nostalgia, and fierce loyalty,

Subtract contemporary Vietnamese đổi mới economic changes and internet slang,

Add some Catholic guilt, the weekly Penny Saver free section, and just enough American English to avoid jury duty.

And as a result, we have the language of 1990’s Little Saigon, California:

We just moved here. = Tôi mới ‘mu’ (move) đây.

You have a duty to your family. = Con có ‘bổn phận’ (antiquated Sino-Vietnamese to mean obligation, citizen’s official liabilities) với gia đình.

The market has a sale. 5 pounds of apples for 1 buck. = “Chợ đang có ‘seo.’ Năm ‘paon’ táo cho một ‘bức.’

It’s a familial language of living history.

It’s a parental language to instill morality and gratitude.

It’s a mother’s language of survival.

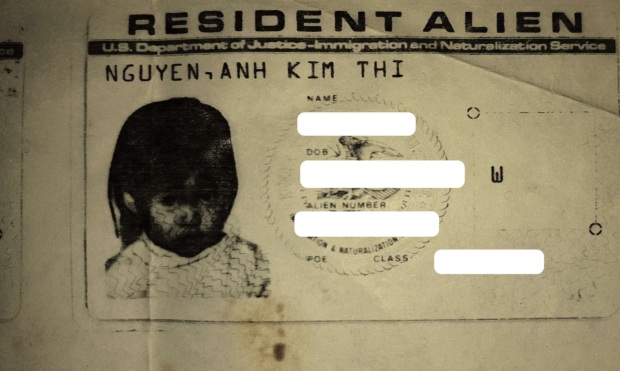

And it was the language that I was raised on. Before I found my time structured by recess, arts and crafts, and English grammar, I absorbed the world around me. I helped my mom cut away the loose threads of her day’s garment work. I watched Vietnamese children’s karaoke and learned about sweeping the house, playing with fireworks, and cooking for your grandparents. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, I traced my mom’s handwriting of my name, Nguyễn Thị Kim Anh.

Utterances of sacrifice, duty, and reputation inserted themselves between meals and commercial breaks. These were the Vietnamese words that guided my everyday. But then I started to learn a new language at school. This language had other rules, speech patterns, and ideals. It was unlike the religious creeds my grandmother whispered, or the ethics of family forever first.

New authority figures who did not look like my parents told me,

“Good job!”

“You can be whoever you want to be.”

“Everyone is different. Cindy has a flat nose.”

“You plagiarized. Your English essay is too good.”

And classmates who were supposed to be something called ‘peers’ told me,

“You are a Communist.”

And I would say, ”No I’m not. I came to America on a boat.”

And then everyone would laugh.

A different set of pronouns and names governed my existence.

At school I was the neutral pronoun “I” and the newly chosen name “Cindy Nguyen,” (“Cin-dy Win,” I would enunciate slowly each day during roll call. Yes, it’s okay, you don’t need to bother with my real name.)

At home I was a child (con) and the affectionate term of endearment “little one” (bé). But more often than not, you would find me in trouble—a disappointment to my entire family, kneeling in the corner and thinking about all of my sins. At that time my parents called me by my Vietnamese name, “Kim Anh”. Or on worse days, they called me, “someone else’s child” (con nhà ai).

I never questioned if I was ‘fluent’ in English or Vietnamese. Until that stale suburban afternoon during my third grade parent-teacher conference, when my mom screeched “My children talk English good! She not ESL. She do good job in school.”

I remember it very clearly as a screech because all the little hairs along the back of my neck stood on end. I replayed in my head not what my mother said, but how she said it. I wanted her to stop speaking, because it resembled the scratching of distorted static—the slow undoing of velcro shoes (something I yearned for) during Catholic confession (something I feared). She sounded foreign, bizarre, comedic even. That day I learned that the English language could be something called ‘broken.’ And for the first time I was embarrassed of my mom.

Day by day, the Vietnamese language that I was raised on turned into a secret language. Take my mother’s version of Vietnamese, then

Multiply by 12 years of American public school peer pressure,

Subtract the ability to read and write Vietnamese,

Add some creative misunderstandings, unspoken teenage resentment, and dreams of the American sitcom family.

As a result, we have the language of my Vietn-America. This language was contained within the perimeter of

The five apartments we lived in during my childhood,

The fifty person weekly reunions with extended family,

The five o’clock afternoon routine of sleepy Sunday mass.

My version of Vietnamese mechanically activates after I enter these spaces. Automatically, my head tilts downwards, my shoulders hunch, and the weight of loss, sacrifice, and misguided hope force my arms to cross over each other.

I lose the ability to look at someone in the eye.

I lose a vocabulary of expression, of empowerment, of individuality.

I lose the pronoun “I.”

School was good. = “Gút”

I’m sorry mom, I made you sad. = “Xin lỗi mẹ, con làm mẹ buồn.”

Thank you Mom and Dad, for taking care of us kids. = “Cảm ơn bố mẹ đã “trông sóc”… (Apparently this is not actually a word, as confirmed by the Vietnamese dictionary, but a creative combination of “trông nom” + “chăm sóc.”)

Your bittermelon soup was delicious! (I love you.) = “Canh khổ qua mẹ nấu ngon lắm!”

It’s a familial language of food (and love).

It’s a child’s language to ask for forgiveness.

It’s a girl’s language of broken translations and dreams.

—

Hanoi, February 2017