Eric’s Note: I am pleased to have street photographer Kramer O’Neill share in this guest blog post his experiences about self-publishing two of his books. It is an incredibly difficult process–check out what he learned through the process in the post below!

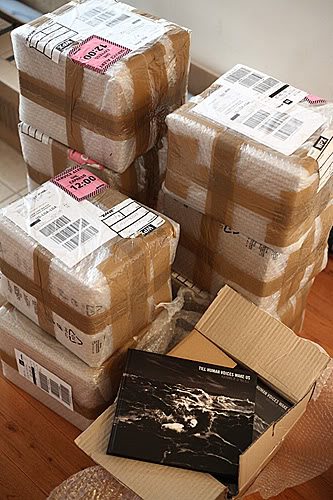

Kramer: In 2011, I designed, printed, and distributed two photo books: Pictures of People and Things 1, an A5-sized paperback, and Till Human Voices Wake Us, a large-format hardcover. The two books are quite different: Pictures of People and Things is an associatively-edited, diverse collection of photos that work as two-page diptychs, while Till Human Voicesis a narrowly-focused, abstract, semi-narrative aquatic series in the street photography tradition, about swimming and the dark pull of the ocean. In both cases, though, I had no idea what I was getting into. In the interest of spreading some knowledge to other would-be self-publishers, here are a few things I learned.

If you want to make a book, you may want to stop this right now

Why? Because if I’d known what it would take, it’s doubtful I would have attempted to make Till Human Voices Wake Us, and without that one, I never would have made its follow-up. How clueless and disorganized was I? Here’s a good example: the aforementioned “follow-up” book came out six months before Till Human Voices (the “first” book) did. So things get a little mixed up, you may lose all track of time, and you will drive yourself and your loved ones crazy. But you should not necessarily let this discourage you! Because in the end, you’ll have [a few hundred] books, and they may even be OK. I am ecstatic about the existence of these books, and grateful I was foolish enough to think I could make them.

There is no “self” in “self-publish”

Just as the director-glorifying “A Film By…” title card dreamed up by those Cahiers du Cinéma kooks ignores all the hard work and brilliance of the other hundred people on the movie set, nobody self-publishes alone. People aren’t just those figures in your photographs; if you have the right people around you, they inspire your work and make you ask important questions, both artistic and practical. There are so many moving parts when you put one of these together, especially distribution-wise: on the most pragmatic level, books take up space, so you may want to spread the storage around, especially if you plan to distribute some on a different continent. They’re heavy, and you can only take so many on the plane with you. Do you know people who would be willing to receive a few hundred books direct from the printer and hold them for months until you can get there? Bonus: can this person/persons do some distribution over there? Have nice friends, it will help immensely. [They may also lend indispensable banking help when, say, you find yourself on the wrong end of your government’s/bank’s absurd prohibition on money transfers to printers in former Yugoslavian EU member states…but that’s another story.]

Be ready to run with whatever happens.

Till Human Voices Wake Us began years ago as a little online project, then became a print-on-demand book, then died an ignominious death from neglect. It was revived by a wonderful woman at a bookshop in Paris who put one of those old POD books in the window, and in so doing, demonstrated that the project could rise again, expanded and refined and properly presented.

But proper presentation and distribution meant a “real” print run, because print-on-demand companies are also their own retailers: they make their profit by marking up the books they send you, so you can’t sell them (again) at reasonable prices without losing money. [And if you’re familiar with POD, you already know that their hardcovers are not thread-sewn; by necessity, they’re bound with an inexpensive, inferior technique – adequate for some things, but not for this.] As the process got underway, though, I found myself in a situation reminiscent of the folktale Stone Soup: much of the impetus for Till Human Voices’ revival proved chimerical – the book was not destined for the instant high-profile feature I’d been promised at another large bookstore. Yet by the time that became clear, it was too late: the wheels were in motion. I and my Paris and New York “agents” had pre-sold enough that things were moving, and, although the book would end up being something other than what I had thought, it basically had to be finished. Which brings us to:

Your book is not the book in your mind (or on your monitor)

This may seem obvious, but when you make a book, it’s unlike any previous form those photos have taken. Even if you have a calibrated monitor and make careful CMYK conversions and use a local printer (instead of printing in Italy and Slovenia while living in Brooklyn), it’s not going to look like you think it will. This isn’t a big deal with a book or two from Blurb, but it is a big deal when you have 500 copies of your book headed for various locations around the globe. Try not to let it drive you crazy. There will be flaws, but there will also be uniquenesses in your work that shine particularly brightly in book form. It’s not a lightbox, it’s not a darkroom, it’s not your computer monitor or even an inkjet print. It’s a book, and that’s something else entirely.

Know your printer’s capabilities and design the book with those in mind.

While assembling Till Human Voices, I started a little side project of discarded photos, an InDesign file that grew to become Pictures of People and Things 1. But what to do with this? Having seen a couple lovely paperbacks by Leïla Garfield, I asked her where she had had them printed and was directed to an industrial printer in Italy. It wasn’t print-on-demand, but it wasn’t exactly a boutique, either. They had a very limited set of parameters within which they would make books. But with those in mind, I was able to effectively craft something I knew they could print well. All the precise design elements I was using in Till Human Voices went out the window: no two-page spreads, no color-profile-specific precision inking techniques. I just converted everything into the most neutral CMYK profile I could devise, sent them a couple pdfs, and received 200 books the next week. They weren’t perfect, but they were what I could do with that particular printing place, and as such, they worked quite well. The artistically-exhaustive, “any-paper-and-binding-combination-in-the-world” Slovenian printers I used for Till Human Voices wouldn’t have wasted their time on a little perfect-bound paperback like that, but in the end, both books are wonderfully printed. They are just very different books, subject/design/printing/binding/cost-wise. Know who you’re dealing with, and the craft will follow. Limitations can be liberating.

Get an ISBN number.

Technically, every book needs one of these in order to be sold legally. In most countries, they are given out for free or for a small processing fee; in the US, the government farms out distribution to “private” corporate middlemen who buy them in bulk and distribute them individually at massive markups. Thus a little more blood gets squeezed out of the 99%.

In CMYK, black is not just black, unless it is, but then nothing looks the same anyway, so what the hell.

I don’t want to linger too much on the technical aspects, but it is very important to understand some basics: computer monitors operate in the red/green/blue (RGB/sRGB) color space, while large-scale printers tend to use cyan, magenta, yellow, and black inks (CMYK). When you give them a pdf, it should be in CMYK, and there are a whole lot of ways to get it there. My experience: Till Human Voices was all scanned B&W negatives that came in as sRGB, were converted to grayscale, then went to a very specific, printer-dictated CMYK color profile for printing. Pictures of People came from scanned negatives (two different B&W film stocks, three color stocks) and digital photos, and ended up in a generic custom CMYK profile that I thought would yield pretty rich blacks while keeping the midtones as neutral as possible.

Getting all those shots to look relatively uniform takes work, and since your monitor can only give you a basic idea of what your files will look like on paper, the Photoshop eyedropper tool is your best friend. Say you converted your image to a CMYK color profile, and now you want to know how much cyan is in that black shadow. Your monitor isn’t really telling you; drag the dropper over it and look at the values. What matters is how much of each ink will hit the paper.

Beg, borrow, steal, borrow some more, take a bad job.

A guy I know, a renowned photographer with two high-profile books in bookstores all over the world, has a funny story about how he got by while making the first book: he worked in the Times Square Disney Store selling junk to tourists. Every day, the supervisor would line up the employees and take a ruler to them, measuring to check that the heels of their shoes were the proper mouse-dictated height. If photography is a glimpse into the money pit, self-publishing is a burial in it.

Printing a thread-sewn hardcover book is all about volume: the more books in the print run, the lower the per-book cost, and it’s not worth paying for the machine setup if you’re printing fewer than 500. So be creative in your fundraising. Although many people like it, I wouldn’t use Kickstarter; I consider their fees larcenous. You can do the same thing for almost no money with email, a website, and/or some well-designed old-fashioned snail mail (which I suspect people appreciate more than anything else). With neoliberalism falling around us, this kind of micro-financing is where it’s at, imo. But guess what? While they will help, pre-orders are not going to get you enough money for a print run. In addition to begging and borrowing, you’re going to have to get an extra job or two. And probably not very good ones.

Shipping costs and credit card cuts add up when you sell from your website, and bookstores generally take 35-40% to sell on consignment, so even selling for double or triple the printing cost won’t put much money in your pocket. With that thin profit margin, it can take years just to break even. Expect to have more than a few ramen noodle dinners.

So why make a book?

Good question. If you have a coherent project, or a series that could be made coherent, having a well-made book that represents it is a great thing. You aren’t just making a book; you’re commencing a process that will take you to new places. As photographers, isn’t this something we always want? It can open doors, it can clarify your work, and it can help generate interest and backing for future projects (fingers crossed on that one). It’s an object that documents the world you lived in and how you navigated through it; you never know what will happen with it, how time will alter people’s perception of the record you created. It’s a time capsule, a time machine, and a great way to present photos. It fuses art and craft in a unique way that can resonate deeply with your audience, simultaneously ethereal and physical.

And not incidentally, it might minimize your stammering the next time you have to answer the question “What do you do?”

Pictures of People and Things 1

Sample images from the book “Pictures of People and Things 1” by Kramer O’Neill.

‘Till Human Voices Wake Us

Sample images from the book “‘Till Human Voices Wake Us” by Kramer O’Neill.

More Information about Kramer O’Neill

If you are looking for an amazing printer, make sure to give Leila Garfield a contact!

Follow Kramer

Interviews with Kramer

- LPV interview on Pictures of People and Things

- Constellation Café on both books and street shooting in general

- Kramer O’Neill on Lenscratch

- Kramer O’Neill on Feature Shoot

Purchase Kramer’s Books

Continue to support Kramer and his future projects by purchasing one (or both) of his books!

If you have had any experience self-publishing and would love to give some advice/feedback–please leave a comment below! Also make sure to let us know what you think about Kramer’s new books too!