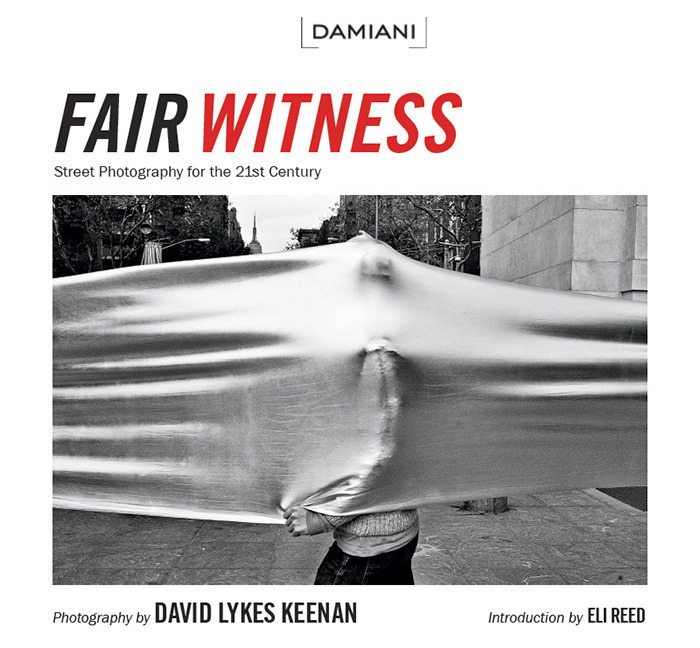

Special thanks to Clifton Barker and Gary Gumanow for putting together this interview with David Lykes Keenan, who is currently fundraising a kickstarter for his “Fair Witness” street photography book.

Clifton: Few have done such great things for the photography scene in Austin as David Lykes Keenan, who I have the pleasure of interviewing today. He founded the Austin Center for Photography and helped it grow during the organization’s first three years. David’s work has attracted some very impressive fans from the likes of Elliot Erwitt and Eli Reed, and ultimately brought legitimacy to the art of street photography in Austin. His book FAIR WITNESS, a collection of photos from NYC, Austin, and other cities, is positioned to be a great success, take a moment and support it on Kickstarter.

Q: Thanks for taking some time and answering a few questions, David. As an Austinite myself, I know how difficult it is to do street photography in a small town. FAIR WITNESS wasn’t entirely shot in Austin, but you have been prolific with your Picture A Week (PAW) updates prior to relocating to NYC. Can you share some advice on making the best of a small town?

Thank you for this opportunity to speak on a subject which I am very passionate about.

I’ll get to your question but I’m glad you mentioned the PAW. I strongly encourage my fellow photographers to do something like this for themselves.

I am proud that I haven’t missed a week with my PAW posting since beginning it in January 2007 although I admit I almost did forget about it the first week of my FAIR WITNESS Kickstarter campaign. That was a hectic weekend.

A PAW can be a great way for your work to be seen and to build an audience – but that’s not the reason to do it. If I have become a good photographer and if FAIR WITNESS is the beginning of my new life as an artist as I hope that it is, I credit my PAW more than anything else in making this come to pass.

Posting a weekly picture, religiously, created a structure for me where I was compelled to look at my work on regular basis, perform edits and evaluations of what pictures I had taken. Perhaps most important, I set a goal for myself that each week’s PAW had to be a better picture than the previous week. Not always an achievable goal, realistically, but it was still the bar I set for myself.

I think this process, incrementally over the years, helped improve my photography. That’s why I recommend anyone with a love for photography and a desire to grow and improve to do something like a PAW.

Okay, back to your question…

For me, I didn’t have any problems photographing on the street in Austin at first. I just wasn’t as visually critical of myself then as I am now. One of the reasons I moved to NYC was that it definitely became harder and harder for me to find pictures in Austin. I think my vision simply outgrew what was available to me as subject matter there.

But, I will add my own caveat to what I just said, and suggest that maybe it is even bullshit. I suspect that the pictures are still there, for me and for anyone. Instead, I think the more probable reason, is that I was just tired of Austin after living there 35 years. The place had become very stagnant for me in many ways, including photographically.

I think that street photography is possible just about anywhere if you are able to bring a fresh eye with you each time you set out to photograph. Some days you will come up empty. But tomorrow is another day and anything is possible. You won’t know unless you’re there in the streets to find it.

Many of the legends of photography, including Russell Lee, Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander, photographed all over the south and southwest, often in cities much smaller than Austin and look at what they accomplished.

I think what separates the ‘greats’ from the rest of us is; they’re always able to experience their surroundings, new or familiar, in fresh ways.

[Editor’s Note: I’d like to add Don Hudson to the list of small town ‘greats’.] Okay.

Q: Can you share your experiences and some practical tips for those of us interested in publishing a book of our own work?

There’s an entire textbook somewhere in a good answer to that question.

The most basic tip is to just do it, as cliche as that sounds. Don’t wait for permission. Don’t wait for someone else to tell you how to do it.

I basically sat on FAIR WITNESS for more than a year while I was waiting on someone on high, so to speak, to make some of the hardest decisions for me, which was the final selection of the pictures to be in the book and what sequence they should be in. I kept deferring to “expert” after “expert”, not trusting myself.

My ‘eureka’ moment came during a talk given by a complete stranger to me at the time. This talk by Dan Milnor, photographer-at-large with Blurb, maybe lasted an hour but it completely changed my relationship with the work which became FAIR WITNESS.

I guess before Dan, I just wasn’t quite ready to accept full responsibility for my own project. After Dan, I suddenly (and honestly, almost explicably) knew that these were MY photographs, no one knew them better than I did, no one knew their relationship to one another better than I did, and I didn’t need anyone’s permission, guidance, or acceptance to create the book.

The final edit and sequence just fell into place in maybe an hour. Of course, I had been living with these pictures for about two years by that time, so obviously a lot more than that hour was involved in what I came up with, but all of a sudden I had what I had been waiting for someone else to create for me.

All that had changed, really, was my attitude.

Make lots of books. All in all, I’ve probably printed at least 10 different versions of FAIR WITNESS. Each one being an incremental improvement over the last. You will know when you’ve made the last one, the one that you want to share with people. For me, the last one will hopefully be made by Damiani.

Publishing a book is a lot of work whether you do it the way I hope to, which is to work with a traditional publisher using the artist-funded model, or if you choose the completely self-published route. Books are expensive no matter how you do them. Look at them as an investment in your life and/or career as a photographer and don’t expect to make a profit.

Bottom line, damn the torpedoes and full speed ahead.

Q: Our mutual friend Gary Gumanow mentioned that you were strongly advised by your father to go into engineering rather than to be a professional creative type. You worked for years developing software—what finally made you give it all up to pursue photography full-time?

Gary is being kind by saying “strongly advised”, I actually felt like I had absolutely no choice. If I was a ballsy-er kid maybe I’d would have gone ahead into photojournalism and ended up being the sports photographer for the Detroit News that I had dreamed of being. But, I was a good boy and always did what I was told to do, so I got an computer engineering degree and, lo and behold, went on to having what ended up being a satisfying career.

Gary probably mentioned this because his son just graduated from high school. He and his son have been facing those very same “what the hell am I (are you) going to do with the rest of your life” questions. With the benefit of hindsight, I think my dad steered me in the right direction, although I certainly didn’t think so at first.

While I can’t say that I even imagined for a second that I’d ever return to photography, that’s what happened.

The jump came very organically and was mostly motivated by burn-out, plain and simple. I mentioned before how I became disenchanted with Austin. No doubt my experiencing professional burn-out as a software developer and becoming bored in Austin were intricately intertwined.

Fortunately, I began my own business in the late 1980s and enjoyed some success with it. So, as long as I was careful, there weren’t going to be financial problems by heading off to reinvent myself as a not-so-starving artist at age 52.

I have been lucky, but I am a firm believer that we each make our own luck.

Q: What would you describe as the single catalyst moment in your life as a photographer? The single most significant moment that made you realize your work would be seen on a large scale?

That’s a very good question. Although, I’d say that I realized that it could be seen on a large scale, not that it would be. Despite all my shameless self-promotion efforts over the past year or so, the jury is still out on any large scale recognition of my photography.

So, with that in mind, it’s pretty easy for me to answer what the most significant moment was.

I mentioned my PAW earlier and how I placed my pictures on the Internet each week for years. Outside of my mailing list of friends and family, I had no idea who might see my pictures. I thought that some of them were pretty good, I won a few Merit Awards from B&W Magazine along the way, but my expectations were very modest.

During that time, unknown to me, Eli Reed was following my PAW. Eli was something of a mysterious legend to me in Austin at the time. I had heard of him via some college kids who took classes from him the University of Texas but had never seen, much less met him.

To make a long story short, Eli eventually contacted me and, quite literally, made it clear that it was time for me to make a book.

Say what?

But that’s what did it. I’m not sure if everyone who might read this interview has heard of Eli Reed. You can read about him on the google.

When I knew that someone of Eli’s stature had been following my photography for I don’t know how long, was impressed enough to tell me it was time for me to publish a book, and was also willing to risk his own reputation by vouching for me, that was when I realized (and accepted) that there could be a large audience for my photography.

Since then I’ve gotten other very significant endorsements, but it was Eli Reed who switched the light on.

Q: You describe yourself as a picture “taker” not “maker,” which I think is selling yourself a little short ;) Truthfully, one of my favorite aspects of your work is the inherent drama from some of your compositions. What makes you “click?”

Pun intended, right?

I wish this question was as easy to answer as the previous one… I certainly “click” a lot less often then I used to. In the earlier years, which actually weren’t all that long ago, I took a lot more exposures than I do now.

Again, I credit my PAW with helping me understand which of my exposures worked as photographs and which ones, the overwhelmingly vast majority, didn’t. Back then I exposed more frames because I was still learning. In art-school-speak, I was still finding my voice.

Now, for better or worse, I do a lot more editing at the time of exposure. I feel like I have a pretty good idea now of what might make a good photograph when I am considering an exposure. I find myself thinking “could this be my next PAW?” (hence a better picture than what was posted last week) and unless the answer is a definite maybe, I don’t “click”.

This makes me think of Gumanow’s hero, Garry Winogrand, and how differently he worked. Is it possible that he and I do work the same way — only Winogrand’s mental photographic editing process operated at warp factor 10 rather than on impulse power?

That was a joke, by the way.

As I walk with my ever-present camera, I am always looking for situations, encounters, juxtapositions, humor, characters, the curious, and the unexpected which I think are the keys to successful street photography. Somehow I just know when enough of these elements are there for an exposure. Then, later, when editing for the next PAW, I look for a photograph.

I do believe that I am a “taker” of photographs rather than a “maker”. Perhaps it is just matter semantics but I take exposures of what I see, of what I stumble upon, rather than creating sets, posing people, arranging props, etc. That’s what I mean.

Q: David, you have been outspoken on the idea of using one focal length to give a definition to one’s work. You shot FAIR WITNESS with 50mm almost exclusively. Can you describe your technical approach to shooting the streets with a 50mm lens? Do you zone focus?

Well, I don’t know if I qualify as someone that can be “outspoken”, but I have discovered that I am most comfortable with a 50mm lens.

I came to this in a pretty obvious way. Back when Leica lenses were only expensive as opposed to outrageously expensive, I purchased a used Tri-Elmar.

If you unfamiliar with this lens, it is as close to a zoom lens as is possible with rangefinder camera. With the turn of a ring, I am able to set the lens at one of three focal lengths: 28mm, 35mm, or 50mm.

I discovered as time went by, I barely ever rotated it away from 50mm. I learned that my mental photographic editor “saw” most often within the the field of view of a 50mm lens. I have kept the Tri-Elmar because it’s practically an investment object these days but I almost always have a fast 50mm lens on my camera now.

I don’t zone focus. I did with the Tri-Elmar in instances that it was set at 28mm and, less often, at 35mm because I could be sure that depth-of-field was working n my favor. Now with a fast 50mm, which I prefer to use at larger apertures (specifically because I like shallow depth-of-field), zone focusing doesn’t work so well.

Therefore, I’m aware that I must always be ready to focus. I’m sure I’ve missed some potential photographs because I couldn’t “click” as quickly as I might if I could count on depth-of-field to ensure focus. I have accepted that this comes with the 50mm lens territory.

Q: How do you interact with your subjects before or after the shot? Does the 50mm focal length give you enough distance to go unnoticed most of the time?

It’s true that I’m probably not close to my subjects very often compared to a photographer using a wide-angle lens. This increased distance probably does help make me less visible.

I rarely interact with the people in my pictures. There are occasions where I’m noticed when I don’t want to be — in those cases, if there is eye contact, I will smile, nod, and/or wave to acknowledge the other person and to send a thank you, and then I walk away.

The only time I have ever been seriously hassled for taking pictures was in Montreal. There, in the span of about four days, it happened three times, and the last time resulted in me having to explain myself to Canada’s equivalent of Homeland Security. So much for easy-going Canadians, right?

Q: One last question. Chocolate or vanilla?

Pistachio.

I always have to be different.