Your cart is currently empty!

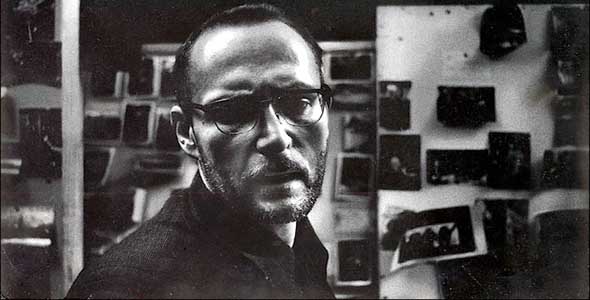

7 Lessons W. Eugene Smith Has Taught Me About Street Photography

W. Eugene Smith is one of the legends of photography. Although he was notorious for being maniacal, emotionally distant, and unreasonable– he channeled those energies into being one of the best photographers history has ever seen. I consider his approach to be very similar to that of Steve Jobs.

I hope that this article can help you get a better understanding of W. Eugene Smith, his work, and his philosophies of photography– to take your own work to new heights.

1. Have a purpose for photographing

W. Eugene Smith was a humanitarian photographer. He documented countless wars, social issues, and even put his life on the line in doing so. He wasn’t interested in just making pretty photos– he wanted his photos to create an emotional resonance with his viewer, and to bring a certain story to life.

In a rare interview in 1956 with the great portraitist Philippe Halsmann they discuss the point of why W. Eugene Smith photographs the way that he does:

Halsmann: “When do you feel that the photographer is justified in risking his life to take a picture?”

Smith: “I can’t answer that. It depends on the purpose. Reason, belief and purpose are the only determining factors. The subject is not a fair measure.

I think the photographer should have some reason or purpose. I would hate to risk my life to take another bloody picture for the Daily News, but if it might change man’s mind against war, then I feel that it would be worth my life. But I would never advise anybody else to make this decision. It would have to be their own decision. For example, when I was on the carrier, I didn’t want to fly on Christmas Day because I didn’t want to color all the other Chistmases for my children.”

W. Eugene Smith was often at the front-lines of many conflicts and wars– when his life was literally on the line. But he wasn’t putting his life at risk for the sake of it. Rather, he had a clear purpose. He knew exactly what he wanted to capture because he had a reason and a purpose behind his photos.

Takeaway point:

Often times us as street photographers have a hard time figuring out why we photograph. However this is a very important question to ask ourselves, or else we are just wasting our time.

Are we out there trying to just take snapshots? Or are we trying to capture something deep and meaningful about society? Are we trying to discover ourselves through our photography? Are we trying to connect with a community or individuals to show their way of life with the rest of the world?

This is a question you can only answer yourself.

2. Be respectful

Although W. Eugene Smith was notorious for being aggressive person and a recluse, he was at heart, a humanitarian photographer. He genuinely cared about his subjects, and wanted to photograph to show social injustices and bring light to facts through his photography.

There were many times in which he captured intimate moments. But how could he capture these moments without intruding and being respectful? For example, there was a case in which W. Eugene Smith used a flash to photograph a mourning family. Halsmann challenges Smith in their interview on why he used a flash and decided to “intrude” this emotional moment:

Halsmann: “I remember particularly your pictures of a Spanish wake [above], of people looking at the dead man’s face — how many exposures did you make?”

Smith: “Two, and one to turn on. I didn’t wish to intrude.“

Halsmann: “Piero Saporiti, the Time-Life correspondent in Spain, told me once that you had used petroleum lamps.”

Smith: “Saporiti has a marvelous memory, so imaginative! This was my version of available light. I used a single flash in the place of a candle.“

Halsmann. “Here were people in deep sorrow and you were putting flash bulbs in their eyes, disturbing their sorrow. What’s the justification of your intrusion?“

Smith: “I think I would not have been able to do this if I had not been ill the day before. I was ill with stomach cramps in a field and a man who was a stranger to me came up and offered me a drink of wine which I did not want, but which out of the courtesy of his kindness, I accepted. And the next day by coincidence, he came rushing to me and said, ‘Please, my father has just died, and we must bury him and will you take me to the place where they fill out the papers?’

And I went with him to the home and I was terribly involved with the sad and compassionate beauty of the wake and when I saw him come close to the door, I stepped forward and said, ‘Please sir, I don’t want to dishonor this time but may I photograph’” and he said, ‘I would be honored.‘”

W. Eugene Smith continues by sharing that potentially intrusive photos are only justified in having an important purpose:

“I don’t think a picture for the sake of a picture is justified — only when you consider the purpose. For example, I photographed a woman giving birth, for a story on a midwife. There are at least two gaps of great pictures in my pictures.”

Smith also brings up the point that being human is more important than being a photographer. In certain life-or-death situations, to help your subjects is more important than just making a photograph:

One is D-Day in the Philippines, of a woman who is struggling giving birth in a village that has just been destroyed by our shelling, and this woman giving birth against this building — my only thought at that time was to help her. If there had been someone else at least as competent to help as I was then, I would have photographed. But as I stood as an altering circumstance — no damn picture is worth it!“

Takeaway point:

As photographers, our purpose is to take photographs that have purpose. However at the same time– there are situations in which we are put into uncomfortable conditions in terms of ethics. When is it right or wrong to take a photograph?

If we can take a cue from Smith, it is that we need to once again– be very purposeful when taking a photograph. Are you just taking a photograph in the hope of getting lots of “favorites” or “likes” on Flickr or Facebook? Or are you trying to say something deeper about humanity through the photograph that you are capturing?

As street photographers, we also dance between the grey line of the ethics of photographing people. However remember at the end of the day, it is important to be a human being first, a photographer second. If there is someone who genuinely doesn’t want you to photograph them– I would respect that.

Also don’t just see your subjects as content. They are living, breathing, human beings. Connect with them, treat them with respect, and treat them like how you would like to be treated yourself.

3. On posing photos

One fascinating interview question that Halsmann asked Smith is about the ethics of posing a photograph. During this time, the philosophy of Henri Cartier-Bresson was that it was “unethical” to pose any photograph (although some of HCB’s most famous photos in history were indeed, staged. You can just see the contact sheets of the transgender man in Spain).

Smith didn’t see it as a problem to pose a photograph, as long as it was to intensify the authenticity of a place or a scene. He elaborates below:

Halsmann: “I remember your picture of a Spanish woman throwing water into the street. Was this staged?”

Smith: “I would not have hesitated to ask her to throw the water. (I don’t object to staging if and only if I feel that it is an intensification of something that is absolutely authentic to the place.)”

Halsmann: “Cartier-Bresson never asks for this…. Why do you break this basic rule of candid photography?”

Smith: “I didn’t write the rules — why should I follow them? Since I put a great deal of time and research to know what I am about? I ask and arrange if I feel it is legitimate. The honesty lies in my — the photographer’s — ability to understand.”

Takeaway point:

Street photography is generally understood as being about candid photographs taken in public places. However there have also been very famous street photographs taken in history which were posed (and not exactly candid). For example, when William Klein took a photo of a kid with a gun he told the kid: “Look tough!” Another case was in which Diane Arbus took a photograph of kid with a grenade in a park. The kid was looking straight at the camera, with an awareness that he was being photographed (not exactly candid).

I think that street photography is often best when candid– but it doesn’t have to be. As long as you are trying to capture something authentic about the person, I feel it is fine. I think Smith would agree as well.

About 90% of the photos I take in the streets are candid, while 10% of them are posed. I generally take candid photos of people, and sometimes interact with them afterwards and ask to take a posed portrait of them. It is a great chance for me to interact with my subjects, and get to know them better.

There are other cases in which I want to be more respectful to my subject, and ask for their permission to photograph them. I generally have found that a more “genuine” expression shows through them when I ask them not to smile. It is a tip I learned from Charlie Kirk and Martin Parr as people generally don’t smile when they are out and about on the streets.

Whether or not you prefer candid or posed images– just remember, try to gain understanding of your subject and follow your gut.

4. Have control over your images

W. Eugene Smith was obsessive when it came to printing his own work. He wouldn’t stop until he created what he believed was a “perfect” print. Why was he so obsessive when it came to this? He shares to Halsmann:

Halsmann: “Why do you print your own pictures?”

Smith: “The same reason a great writer doesn’t turn his draft over to a secretary… I will retouch.”

Takeaway point:

To some people, it is very important to have creative control over how a photograph looks in the end.

Of course now that the majority of us shoot digitally, we no longer print our images–but post-process them. For those of us who do shoot film, either we send it to a lab or process it ourselves.

I personally don’t think you have to always post-process or develop your own film. For example, Henri Cartier-Bresson knew how to (but wasn’t very interested) in developing and processing his own film. He would also get his work printed by a master printer the he trusted. He was more interested in photography.

Personally I don’t really process my own work either. For my color work, I send it to Costco and get them to scan it for me (a great deal at $5.00 USD). For black and white work, of course I develop it myself (sending it to a lab is too expensive) but I prefer to have someone else do it if I can. I am more interested in photographing.

However I think what we should focus on is consistency in terms of the output of our images. For example, if you shoot digital– use the same preset or try to simulate the same “look” in your photos every time. If you work in black and white, don’t have some photos that have low contrast, high contrast, and others sepia. Keep it consistent.

The same goes with color– don’t make some of your images desaturated, some of your images high-saturation, or add limo effects to only some of your photos. Keep your ‘look’ consistent.

With you film shooters, I recommend sticking with one type of film and processing method for a long time. I think it is fun to try out new types of films, but in the end– try to stick to one (once you find one you like). Personally I prefer Kodak Portra 400 (the new one) for color, and Kodak Tri-x for black and white (you can’t go wrong). And for your developing methods, try to use the same chemicals and processing times.

5. Take your time

W. Eugene Smith literally put his life into his work– and it killed him (literally). He often took lots of drugs to keep him constantly producing work and printing his photos– and did it for his entire life (until he passed away tragically at an early age).

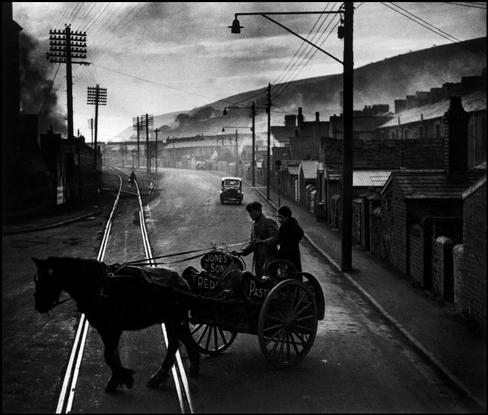

One of the projects that he spent a lot of time and energy was his Pittsburgh project. What was supposed to be a three week project turned out to ~17,000 pictures (~472 rolls of film), in his “Dream Street Pittsburgh Project.”

To the disdain of his editors, he kept working on the project– and refused to stop until he felt that it was complete or finished. Smith explains the importance of time in terms of the project (and life):

Halsmann: “How much did your Pittsburgh Opus cost in time?”

Smith: “It cost the lining of my stomach, and much more beside. … While working on it I resigned (from a certain unnamed picture magazine).”

[At this point in the transcript, the Q. and A. format is broken, though it goes on: “After questioning back and forth, Philippe pinned him down to this: Smith had explained that he had worked on the opus for a period of several years, which included three months that he was on staff, which he considered ‘stolen.’“

Smith expands on why his project took so long, and why he needed so many images to complete his vision:

Smith: “There’s no way to evaluate it,” Smith said. “If I was able to print exclusively, it still would take at least a year. I now have 200 prints from 2,000 negatives….”]

Halsmann: “What would anybody in the world do with 200 prints?”

Smith: “Each print I have made represents a chapter — the 200 represent a synthesis.“

Halsmann: “You won’t put any time limit on this work?”

Smith: “It was also sidetracked for a period of time for doing an almost equally difficult color project — one of my worst failures, which I consider a going to school.”

Takeaway point:

17,000 pictures or roughly 472 rolls of film is a prodigious amount of photos (even by digital standards). However Smith wasn’t just photographing like crazy just for the sake of it. He had a certain vision of Pittsburgh he wanted to convey– which took him a long time (and through a lot of photographs).

Smith suffered lots of doubts and setbacks in his Pittsburgh project, but he continued to persevere and take his time. He had all these editors and outsiders clawing his back to rush his project (after all the project was initially supposed to only take three weeks) but Smith took the unreasonable route and continue his project.

We often rush our own work. We don’t let our photos sit and marinate long enough, and we often don’t spend enough time editing our shots. Therefore this leads us to uploading too much work on the internet, some which are good– but others which are only “so-so.”

I think especially in today’s digital age: less is more. To show less work is to show more discipline of yourself as a photographer. Not only that, but the work that you put out will obviously be stronger as well.

So don’t feel the need to rush things– take your time with your work. The best projects take years, or even decades to finish. Take your time, and you will be rewarded.

6. Don’t worry about the finances

When Smith was working on his Pittsburgh project, he faced many financial setbacks. He wasn’t making money at the time, he was borrowing money from his family, and constantly short on funds (he could barely afford film and paper to print on). However he didn’t let this set him back. Halsmann inquires about the issue of finances:

Halsmann: “How can this be financed? Is there any way, here in America today, to pay a man back for this work?”

Smith: “How long did it take Joyce to do “Ulysses”? I could never be rested within myself without doing this.“

Halsmann: “But what if the photographer does not have the financial means?”

Smith: “I will advise them not to do it, and I will hope they do.“

Halsmann: “What if nobody sees it? Besides a few friends?”

Smith: “Answer this and you will see how artists have acted throughout the bloody ages. The goal is the work itself.”

Takeaway point:

This is quite possibly one of my favorite excerpts from Smith. He was a man who didn’t get a damn about the issues of finances, fame, or reputation. He was only interested in making great work– it was an end into itself. He didn’t even care if nobody ever saw the photos, he had a deep drive in himself to create this work.

We are all social beings–and we crave for attention and admiration from our peers and family. It is natural. However at the same time, this can be a slippery slope. Rather than doing work for the sake of it, we do it to please others.

When it comes to street photography, we can also get suckered into getting praise for our photos (rather than making great photos). How many “likes” or “favorites” is enough?

We should shoot in the streets as an end in itself. Meaning, we do it for the sake of it– to improve our own work for our own love, rather than trying to impress others.

An easy antidote to focus on your own work: take a hiatus from sharing your work on social media for a year. Trust me, it seems like a long time– but it passes pretty quickly and it will probably help your photography incredibly. I know it did for me.

About a year ago from the advice of Charlie Kirk I decided not to upload any of my new work for a year. Sure it was incredibly difficult (I have always been a sucker for getting lots of views, likes, and favorites) but it helped me focus on my own photography. It made me focus less on the admiration of others, and more on myself– to create great images for myself.

Nowadays I’m sharing more of my images that I have shot from 6 months-year ago, but I still try not to share too much of my work. I find once I get into the habit of regularly uploading work, once again– it causes me to get hooked on external recognition and validation, rather than my own validation (and that of close friends and colleagues).

7. Tell a story

Dr Robert CERIANI making his way to visit his patients by foot in their remote villages. Copyright: Magnum Photos

One thing that I always admired from W. Eugene Smith was his ability to make incredible “picture stories.” Some of his works come to mind like the Japan Minamata Bay series in which he photographed the after-effects of toxic merry poured into the river (and the effects on its civilians). My other favorite project of his was his “Country Doctor” series in which he spent 23 days following a doctor in Colorado, documenting his day-to-day challenges and interactions with his patients.

W. Eugene Smith had a burning curiosity to “go deep” with his projects. He didn’t just take a few pretty photos and take off. Rather, he embedded himself into the lives of his subjects and got to know them inside and out. This helped him create intimate portraits and images which really told stories. The way that he also edited and sequenced his photographs also added to the “picture story” which was famous with LIFE magazine in the 50’s.

Takeaway point:

Nowadays with social media, I would say that working on projects or a “picture story” is a lost art. The majority of street photographers focus on single, memorable images (rather than larger projects which have more of a story and depth behind it).

Don’t get me wrong, I love memorable single images. However I think that at the end of the day, they pale in comparison to projects which have more depth and soul and get to know people on a deeper level.

Therefore I recommend you rather than just focusing on single images, to work on longer-term projects. You can start working on your own street photography project with this article: “How to Start Your Own Street Photography Project.”

Conclusion

W. Eugene Smith was one of the great photographers of history who didn’t take bullshit from anyone else– and follow his own gut and soul when it came to his own work. Although he wasn’t the friendliest guy and a bit neurotic at times, he had deep compassion for his subjects and a burning sense of curiosity which helped him connect on a deep level with those he photographed.

I think as street photographers, we can learn much from his philosophies (and his stunning images).

Don’t worry so much about fame, recognition, or money when it comes to photography. Let’s follow in Smiths’ footsteps and do the work as an ends to itself– to uncover something about society and for ourselves.

Quotes by W. Eugene Smith

Below are some of my favorite quotes by W. Eugene Smith:

- “The world just does not fit conveniently into the format of a 35mm camera.”

- “Never have I found the limits of the photographic potential. Every horizon, upon being reached, reveals another beckoning in the distance. Always, I am on the threshold.”

- “Passion is in all great searches and is necessary to all creative endeavors.”

- “I’ve never made any picture, good or bad, without paying for it in emotional turmoil.”

- “I wanted my pictures to carry some message against the greed, the stupidity and the intolerances that cause these wars.”

- “…and each time I pressed the shutter release it was a shouted condemnation hurled with the hope that the picture might survive through the years, with the hope that they might echo through the minds of men in the future – causing them caution and remembrance and realization.”

- “Whats the use of having a great depth of field if there is not an adequate depth of feeling?”

Further Reading

Skyline view at night, with the Delaware River. Copyright: Magnum Photos

- W. Eugene Smiths’ Magnum Portfolio

- Essay: W. EUGENE SMITH: “W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Photographs” (2001)

- Interview: W. Eugene Smith: ‘I Didn’t Write the Rules, Why Should I Follow Them?’(What I quoted for in this article)

W. Eugene Smith Documentary

Below is a superb documentary done on W. Eugene Smith. Highly recommend everyone to watch this, to get a better understanding of his character and passion:

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (1/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (2/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (3/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (4/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (5a/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (5b/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (6/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (7/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (8/9)

W. Eugene Smith: Photography Made Difficult (9/9)

Photos by W. Eugene Smith

Below are some of my favorite photos by W. Eugene Smith (which weren’t included above):

Books by W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith (2011)

If you can just have one book on W. Eugene Smith, this is the book to get. A superb collection of his life’s work.

Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project

The photos from his notorious Pittsburgh Project. Probably his most memorable body of work (that he put the most life into).