Your cart is currently empty!

10 Lessons Josef Koudelka Has Taught Me About Street Photography

Don’t miss out on the re-print of Koudelka’s book: “Exiles“!

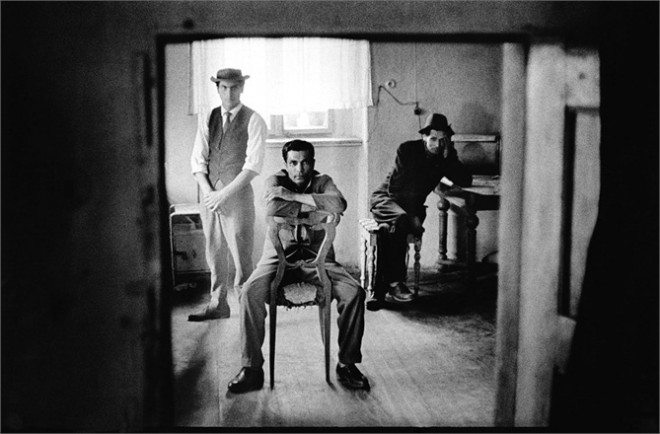

To me, Josef Koudelka is one of the most brilliant photographers out there and a true master of black and white. Not only does his work carry a strong sense of composition, form, and geometry but they also carry an emotional impact. His photos are raw, gritty, and show both the hope and melancholy of life.

I was first introduced to Koudelka’s work by my good mate, Bellamy Hunt around two years ago. I was staying with Bellamy for a week in Tokyo, and I was rummaging through some his photo books. I asked him what his favorite book was, and Bellamy said: “Exiles” without even a second thought.

I pored through the book, and was amazed by the brilliance of the photographs. When I went back to the states, I did more research on him, and started to become more and more enamored by his work.

I hope this article can be a good introduction to the work and life of Josef Koudelka. He is notorious for not talking much about his work, but he has done several interviews in the past which give an insightful look into his creative process and how he photographs in the streets.

1. Experiment with other types of photography

One of the most interesting things I discovered about Koudelka while researching him is the fact that his first real interaction with subjects started when he photographed for a theater magazine. He worked in the theater photographing the performers– which allowed him to refine his technique, composition, and stark contrasty style. Not only that, but it gave him the financial independence to pursue his interest in photography.

So what was Koudelka like when he was photographing the actors on stage? Well according to Otomar Krejca (the famous Czech theater director), he was a master of capturing the action of the actors without disturbing them. Not only that, but he was very focused when photographing:

“He gave us an unusual show: he was an enlightened walk-on player, causing no trouble at the rehearsal, sliding easily among the actors—or rather their characters. But he was not performing. Totally absorbed by the drama, he moved in a way that did not disturb the choreography of the characters, whether he came in close to catch a detail or stepped back for a group view. He was very focused on his work.”

What then surprised Krejca was when he first saw Koudelka’s images of the actors. He realized that Koudelka didn’t just capture the costumers of the actors, but their soul and emotions:

“We recognized the actors, but their faces were not their own; these were not banal mortuary masks of their living counterparts, but the real life of the characters they represented. These were the distinguishing moments, the supreme instants, which he had captured live, which he had seized during the play, a sensitive to the movement of the interior lives of the characters onstage, in those performance shots Josef found and caught the emotional knots – each actors most fully charged moments—when the traits of their characters, shaped by an organic emotion, took on the rosy hue of human flesh.”

Therefore by first starting to photograph in a theater allowed him to gain the necessary training and skills to pursue something less controlled: his journeys with the Roma people. (Nowadays the term “Gypsy” is politically incorrect, but from this point in the article I will refer to the Roma people as “Gypsies” as it will be easier to follow).

Between 1963-1970 Koudelka started to travel and document the journeys of the Gypsies. He often slept outside, with very little food, but built a very strong and emotional connection with them.

So how did Koudelka apply his experience photographing the theater when it came to photographing the Gypsies? Well, in an essay written by Michel Frizot (a French photography historian) he explains the parallels:

“If we consider his chronology, Koudelka began by photographing the theater; it was the theater that placed the camera between him and the world, that taught him to roam in order to obtain what could be a meaningful angle, to find the significance in a scene. The theater, unquestionably, provided training in foreground/background, blocks of light, facial expressions, instances of interaction.”

Takeaway point:

Don’t feel that the streets is the only place you can improve your photography skills. In-fact, I feel the fields outside of street photography can probably best help your street photography.

For example, you might be a wedding photographer. One of the most important things I think a wedding photographer has to do is to capture “the decisive moment.” You cannot miss “the kiss.” Not only that, but you have to be good at interacting with people.

I think the same applies in the streets- you want to be good at capturing those split-second moments and be good at interacting with people in the streets as well.

This can apply to tons of other fields of photography.

Do you shoot a lot of landscape? If so, the background is probably very important to you. Apply that to street photography.

If you shoot macro photography, you might be interested in capturing details. Try to do that, but turn your lens towards people.

Don’t feel obliged to only shoot in the street.

2. Let your photos do the talking

I think one of the best things about photography is the democracy behind it. I think photos are more interesting when they are left open to interpretation when the viewer can make up his or her own little story about a photograph.

In an interview with Koudelka, he says the following about how he doesn’t like to talk about his photos rather, he likes to do the photos do the talking:

“I tried to be a photographer. I don’t know how to talk. I’m not interested in talking. If I have something to say, perhaps it can be found in my photos. I’m not interested in explaining things

in saying “why” and “how.”

Koudelka also hates adding captions or descriptions to his photos (other than a simple location or a date). Rather, he believes in the idea of others explaining what his photos mean:

“I leave it to others to say what they mean. You know my photos, you published them, you exhibited them, and so you can say whether they have meaning or not.”

Takeaway point:

I often find when photographers spend too much “explaining” their photographs, it is because the photograph is not very interesting without an explanation.

I think that there are certain photos that do need explanation (political, war, or documentary photos). However the beauty of street photography is that we aren’t bound by the same amount of standards for “objectivity.”

Therefore, I think that our street photos should be as subjective and personal as possible. Not only that, but to make our photos more interesting, leaving them up for questions is often better. It makes the photos more ambiguous, and gets the viewers to participate in your photos and make a fun story of what they think is happening in the frame.

3. On using different lenses for different projects

Gypsies, which is one of my favorite projects by Koudelka, was photographed with a wide-angle 25mm lens. I feel that it was crucial that he used this wide-angle lens, because most of the photography he did was indoors, in very cramped situations. Therefore, if he didn’t use a wide-angle lens, he wouldn’t be able to give a sense of place to his photographs and context.

When interviewed by Vogue, Koudelka expands on the importance of using wide-angle lenses for his “Gypsies” project, and how it influenced his vision:

“The “Gypsies” project is a product of wide-angle lenses. I bought them by chance, from a widow who was selling everything. It changed my vision.”

He gives an example of a photo in the book that couldn’t have been achieved without a wide-angle lens (a photo of a little girl in the midst of people):

“It was perfect for this picture, for instance.It was such a small space. It wasn’t much bigger than this [shows small space with hands]. I was sitting there, with all these people sitting around me—when I made portraits I only featured one person. Here they all entered the picture.”

Koudelka also shares another photograph which wouldn’t have been possible without a wide-angle lens (one of a bunch of Gypsies dancing around a cramped house):

“Or have a look at these, you can only take this with a wide-angle lens.”

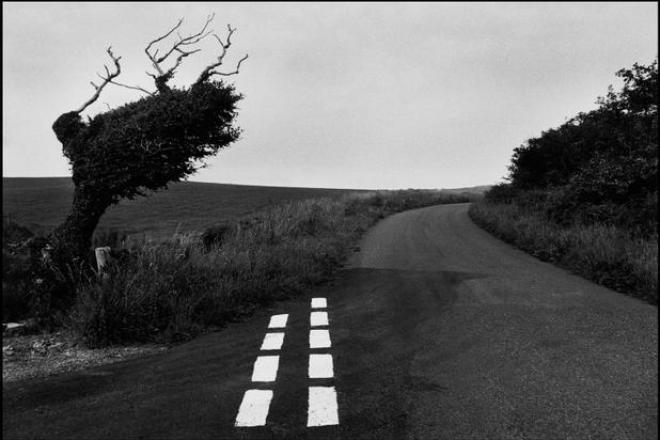

However when Koudelka left Czechoslovakia, he realized that he needed to switch his focal length to better suit his subject matter. He was no longer shooting in cramped indoor places. Rather, he was dealing with large outdoor places, in which he started to shoot more with a 35mm and 50mm lens.

Not only that, but he realized that he wanted to switch up his style and approach:

“When I went out of Czechoslovakia I experienced two changes:

The first one is that there wasn’t this situation any longer. I didn’t need wide-angle lenses. And I had understood the technique very well, I was repeating myself, and I’m not interested in repetition, I wanted to change. I took a 50mm/35mm Leica.

The second change was that I started to travel the world. I had this possibility and I had a look at this world.”

Takeaway point:

I prefer to use wide-angle lenses for street photography, as I feel they are much more intimate. When I look at Koudelka’s photos from his “Gypsies” project, I feel like I am with them dancing, eating, and experiencing life with them.

However it is also important to note that certain lenses tend to be better in different situations. For example, you wouldn’t bring a fisheye lens to a baseball game if you wanted to zoom into the outfielder.

Koudelka experienced that after his Gypsies project he needed something not as wide- and switched to a 35mm and 50mm for his travels.

So if you are working on a certain project that has cramped quarters, you might be best off using a wide-angle lens. I found that wide-angle lenses work best in crowded cities with small sidewalks. However if you have more space, or shoot in a more rural place– perhaps using a more standard lens like a 35mm or a 50mm might suit you better.

4. Letting your photos marinate for a long time

Koudelka is best known for four projects: Gypsies, The Prague Invasion, Exiles, and Chaos.

Koudelka has been photographing since his early twenties, and now is a 75 years old. That is close to 70 years of photographing. If you apply that math to his four projects– then on average, each of his projects have taken him 15-20 years.

Koudelka also shoots a lot. So how does he manage to be disciplined enough to edit down his own work and be utterly critical with himself?

Well one of his ways of working is to make small prints of his photos, hang them on his wall, and look and compare them for a long time before deciding to keep them, ditch them, or how to arrange them in a book/exhibition:

“I’m willing to show my photos, not so much my contact prints. I often work on small prints. I look at them frequently, and for a long time. I put them up on the wall, and compare them, to make sure of my choice.”

Koudelka, like many of us, aren’t sure what his “best” photographs are. So one thing he also does is print his “maybe” photos as well to make a better determination of how good his shots are.

Takeaway point:

Photographers tend to be really bad at editing their own work. Why is that? Because we get emotionally attached to photos (that may not be very good). But because the story behind a photograph may be memorable to us, we want to keep it. However at the end of the day, we need to be critical with ourselves and think if our photos can stand on their own (without some embellished story propping it up).

I personally have a very difficult time editing my own work. But if there is one thing I learned from Koudelka is the importance of letting your photos sit for a long time, and letting them marinate like a nice steak or letting a good wine age for a very long time.

I think ever since I started to shoot film it has helped me with my own self-editing. How so? Well first of all, I don’t process my photos until at least a month or two after I take my photos. Therefore, I forget the majority of the photos that I took– so when I make my rough edits, it is like I am editing someone else’s photos (not my own).

Another thing I do is wait a long time before I upload any photos to the internet. I carry around my photos in my iPad, and always show them to friends and photographers I trust. I ask them for their critical opinions, and to “tear up” my work. They then help me edit down my photos, make sequencing suggestions, and even project ideas.

Whenever I do upload photos online, I have waited for at least 6 months to a year before I can really ascertain if they are “good.” And this is a combination of my own self-editing, and feedback from friends/colleagues. I personally think it is impossible to edit your own work 100% honestly, because you will always be emotionally involved with your own photos somehow.

If you are shooting digitally, here are some tips to be better at self-editing. Some of these tips will also work with film:

- a) Don’t chimp

- b) Don’t download your photos directly to your computers after a day of shooting. Rather, let your photos accumulate for at least a week

- c) When you import your photos to your computer, do a rough edit and create a “maybe” folder for your potential good shots

- d) Get small 4×6 prints of your photos, then tack them to your walls, and start slowing removing photos you don’t like.

- e) Bring your 4×6 prints with you (or put them on an iPad) and share them with fellow street photographers (in-person) and ask them to be brutal with you and help edit down your work

- g) Make the final decision of uploading your best shots online, for the rest of the world to see.

5. Keep up the hustle

One of the previous things I mentioned which is so great about Koudelka is the fact that despite his age, he continues to photograph and challenge himself.

He explains his burning passion to continue photographing:

“Many photographers like Robert Frank and Cartier Bresson stopped photographing after 70 years because they felt that they had nothing more to say. In my case I still wake up and want to go and take photographs more than ever before. But I can see that a certain type of photography has come to an end because the subjects don’t exist anymore. From 1961 to 1966 I took pictures of Gypsies because I loved the music and culture. They were like me in many ways. Now there are less and less of these people so I can’t really say anything else about them.

What I can do is update projects like “The Black Triangle”, as that is about a specific landscape that doesn’t exist anymore. I can show how it was before and how it is now, so people realize what’s going on. That keeps me excited.”

Not only that, but the fact that Koudelka hates repeating himself and loves challenges fuels his passion to photograph:

“I am not interested in repetition. I don’t want to reach the point from where I wouldn’t know how to go further. It’s good to set limits for oneself, but there comes a moment when we must destroy what we have constructed.”

At times we may lose the passion to photograph. But perhaps another way to stay motivated to continue to shoot is to pretend like everyday is your last:

“When I wake up in the morning, and I feel good, I tell myself: ‘Today may be the last day of my life.’ That is my sense of urgency. But I keep wondering about what you just said, that I am a conscience. People have told me that. People much younger than myself have told me: ‘I would like to work as you do.’”

Takeaway point:

We all fall into creative ruts and lose inspiration. However rather than thinking about our shortcomings as photographers (and what has already been done before) think about the possibilities and pushing boundaries.

Often times we get bored when we end up repeating ourselves so much. Whether it be the approach, subject matter, or project. The moment you find yourself repeating yourself or bored of your photography, mix it up. Try out something different.

Not only that, but realize how blessed you are to be alive. If you were to die tomorrow, would you be satisfied with your photography? If not, perhaps you should shoot everyday like it was your last.

6. Photograph for yourself

Although Koudelka is a brilliant photographer, he too has his critics. What does he think about his critics? Does he care about what they think?

“Certainly not…I don’t care what people think, I know well enough who I am. I refuse to become a slave to their ideas. When you stay in the same place for a certain time, people put you in a box and expect you to stay there.”

Koudelka expands on the idea of the importance of shooting for oneself, and ignoring things like money or fame:

“Too often people with some talent go where there is some money to be made. They begin to trade a bit of their talent for a bit of money, then a little more, and finally they have nothing left to themselves. In Czechoslovakia we didn’t have many freedoms, and particularly not the freedom to make money. But that led us to choose professions that we really loved. I always photographed with the idea that no one would be interested in my photos, that no one would pay me, that if I did something I only did it for myself.”

In another interview Koudelka reiterates the point that he only shoots what he finds interesting, and values his freedom above everything else:

“I photograph only something that has to do with me, and I never did anything that I did not want to do. I do not do editorial and I never do advertising. No, my freedom is something I do not give away easily. And I do not follow the war because I am not interested in photographing violence. Sure, if I was in Georgia now, I would be photographing what happens.”

Takeaway point:

It is important to get feedback/critique on your work from others. I think this is one of the best ways to find the shortcomings in your own work, and how to take your work to the next level.

However at the same time, don’t be “a slave to others’ ideas.” At the end of the day, you should photograph for yourself.

Also as a photographer, be careful when it comes to pursuing money or wealth. Sometimes it can lead down the wrong hole, in which you forget why you enjoy to photograph in the first place.

Follow your passions in street photography, and ignore the rest.

7. Don’t think so much when you shoot

When we are out on the streets, sometimes we over-think things. We might spend too much time worrying about the composition, technical settings, light, etc.

How does Koudelka approach his own photography? He focuses on the moment, and doesn’t think too much:

“When I photograph, I do not think much. If you looked at my contacts you would ask yourself: ‘What is this guy doing?’ But I keep working with my contacts and with my prints, I look at them all the time. I believe that the result of this work stays in me and at the moment of photographing it comes out, without my thinking of it.”

Another important part to embrace is to be curious about your work, and not overly philosophize:

“I don’t pretend to be an intellectual or a philosopher. I just look.”

Takeaway point:

Things like composition, technical settings, and light are very important when it comes to street photography. However if you ever find any of those things taking away too much from the experience of photographing, you might want to simplify.

I learned composition intuitively by looking at a lot of great photographs. Over the last year, I have spent over $3,000 dollars to purchase over 50 photo books. By spending a lot of time looking at photos, I start to get a gut instinct if a composition “works” or “doesn’t work” because I have invested time and energy into building my own visual library.

Therefore when I am out shooting in the streets, it allows me to just focus on capturing “the moment.”

The same applies for camera settings. I shoot mostly with a flash on my Leica, and the settings are always the same: Portra 400 film (at 400), f/8, flash at 1.2 meters, pre-focused to 1.2 meters, and 50th of a second. I also tend to photograph most people at around the same distance. This allows me to focus on finding interesting people, interacting with them, and capturing certain expressions or gestures they may have.

Even easier, I recommend most people to shoot with “P” mode on the streets, especially if your subject isn’t moving around much. This is what I do with my Contax T3. I just look, point, and click. I let the autoexposure and autofocus do the rest. This allows me to focus more on composition rather than fumbling with my settings.

So when you are shooting, remember to enjoy the process of shooting. You don’t always have to over-think things.

8. Spend a lot of time shooting

Like baseball, the only way to get better in street photography is to practice. You can read hundreds of books on the theories of baseball, but until you go out and actually hit a ball with a bat, you won’t learn anything.

The same applies to street photography. The only real way to get better is to spend a lot of time outside, and by shooting a lot.

Koudelka explains the importance of shooting a lot:

“If I couldn’t shoot lots of photos, I would not be the photographer that I am. Still, the cost of film has often been a problem. At times, to save money, I had to work with remainders of movie-film, and even to buy film that was stolen. But when I have only three rolls of film left in my bag, I panic.”

Takeaway point:

Nowadays we have the benefit of shooting digitally – which is both a blessing and a curse. Of course the blessing is that we can shoot a lot, and improve in a quick amount of time. I see a lot of street photographers who use iPhones get better in a very quick period of time (because they always carry their camera with them everywhere they go and thus end up shooting a lot).

However the curse is that editing can be a pain in the ass.

But at the end of the day, I still think it is better to take more photos than fewer photos. Even though nowadays I shoot with film and it can be expensive– I still shoot a lot (if I see a scene interesting enough). I have shot an entire roll (36 shots) on just one scene, because I thought it was interesting enough to me.

So remember, always carry your camera with you everywhere you go and try to spend as much time as you can shooting. And yes, smartphone cameras count.

9. Live simply

Koudelka has traveled for most of his life like a nomad. When he was younger, he would spend most of his time sleeping outside or even on the cold hard-wood floors of the Magnum offices.

In an interview when asked why he decided to live this way, he explains the freedom when it comes to living simply:

“I’ve never aspired to have the perfect home, to be tied to something like that. When I bought my home, my main requirement was that I could work here. I live in Paris – this is just another part of my traveling life. I don’t need to fill houses with clothes. I have two shirts that last for three years. I sleep in them. I keep my passport in the top pocket and some money in the other. I wash them in one go and they dry quickly, it’s very simple. *I only carry things that are needed – my cameras, film and a spare pair of glasses.”

Even when he was photographing his projects, he chose to live in poverty to focus on his own work:

“For 17 years I never paid any rent [laughs]. Even the Gypsies were sorry for me because they thought I was poorer than them. At night they were in their caravans and I was the guy who was sleeping outside beneath the sky.”

Takeaway point:

I know a lot of photographers who don’t have enough time to photograph. This is often because they consume too much of their time working.

Of course we all need to make a living, but there is a certain point in which we spend more time working than we need to.

For example, if you are leaving the office, don’t check your work emails or bring work home (if you have the option). Rather, spend that time out shooting, going home and reading some photo books, or meeting up with fellow street photographers.

I know that at my old job, I would end up spending more time in the office and working so I could be more productive. I thought with that extra productivity, I would get a promotion and a raise, and end up making more money to be “happier” in life (by buying more material things like a nice car, nice clothes, a big house, etc).

But at the end of the day, I think we should just work the minimum to meet our basic needs (simple clothes, a simple place to live, and a simple way of living). Then we can spend the rest of the time pursuing what our true passion is: shooting on the streets.

10. Make your photos personal

Although many of Koudelka’s photos are a celebration of life, many of his photos are quite dark and grim. They have a certain sense of heaviness and melancholy.

Do Koudelka’s photos show his own views of the world? When asked about this he agrees:

“The mother of my son, an Italian lady, she once told me, ‘Josef, you go though life and get all this positive energy, and all the sadness, you just throw it behind you and it drops into the bag you carry on your back. Then, when you photograph, it all comes out.’ Perhaps there could be some truth in that.’”

Takeaway point:

At the end of the day, I think photography is all about showing your vision of the world to others. Whether it be happy, sad, or weird (or anything in-between).

Revel in your uniqueness and show your personality through your photographs. Be authentic with yourself, don’t try to copy others’ visions, and your work will shine through.

Conclusion:

Koudelka is a man who made photography the priority of his life. He sacrificed a lot, as he never had the best family life and never spent a lot of time in one place. He was a nomad, always on the go.

But at the same time, he is a man who was brave enough to do things his way. He valued his freedom above everything else, and took his photography very seriously.

Not only that, but he is absolutely brutal when it comes to self-editing his own work. He knows when to kill his weak photos, and spends a lot of time before deciding which of his photos are the best.

At the end of the day, there are many lessons we can learn from his passion, hard work, and genius. But remember, at the end of the day– he didn’t pursue his photography for the money, fame, or to impress others. He photographed for the love of it, and for himself.

References

Below are some of the resources I used to put together this article:

Books:

Articles:

- Social Stereotype: Interview with Koudelka

- The Guardian: 40 years on: the exile comes home to Prague

- Interview with Frank Horvat

Videos on Koudelka

Koudelka: Contact Sheets (Vol. 1)

Below is a superb video showing some of the contact sheets behind some of Koudelka’s most famous images:

Vogue Interview with Koudelka: Gypsies Exhibition

Koudelka gives a rare interview with Vogue about his recent Gypsies exhibition. He talks about his theories on how to put together an exhibition, how to group images, and some of his philosophies on photography

Books by Koudelka

Aperture: Koudelka

An incredible book on the life and work of Koudelka. Contains insightful essays (many of which I quoted from to write this article). And snippets of each of his major projects. Highly recommended, amazing print quality, and a solid investment at ~75 USD.

Gypsies

In my opinion Koudelka’s finest work. For street photographers, this will probably be the best book to get. Unfortunately it is sold out in most places, but you can pick up a used copy on Amazon for ~50 USD. A must-have for any photography library.

Exiles

Now being re-printed, pick up a copy before they sell out!

Prague Invasion

An incredible book showcasing the history of Prague being invaded by the Russians. Koudelka risked his life getting the shots that he did–shooting up and close and personal. Fortunately still in-stock, at only ~42 USD.

Chaos

A book of his panoramic landscape photos. Not really my cup of tea, but if you are into landscape you should pick it up. ~50 USD.

To see more of Koudelka’s work, check out his page on Magnum Photos.